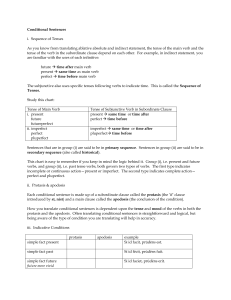

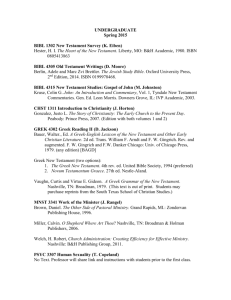

CONDITIONAL SENTENCES IN THE

advertisement