Reisman – Religion-Economy-Culture Modern Turkey – ASREC09

advertisement

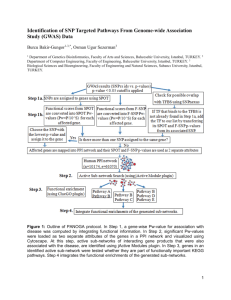

Religion, Culture, and Economy: the case of modern Turkey1 See changes since presubmiission Arnold Reisman2 arnoldreisman@sbcglobal.net ABSTRACT For over four centuries, religion dictated what comprised culture in the Ottoman land we call Turkey. Then, culture was a non factor in the economy, but all that changed when Turkey became a secular republic in 1923. Initially and as a matter of government policy, Turkey’s performing and visual arts were westernized using central and west European talent and these reforms have gained a momentum of their own. Cultural offerings impact the tourist trade. Currently Turkey’s tourism revenues (per-capita) exceed the total GNP (per-capita) of most Islamic countries including that of oil exporting, archeologically endowed, and climatically comparable, Iran. The major factor in the difference is cultural tourism. International Music and opera festivals abound on both the European and Asian sides of Turkey’s land-mass and Istanbul is poised to become the cultural capital of Europe by 2010. Introduction Modern Turkey’s culture is an amalgam of the many civilizations that lived on, crossed over, and enriched its land. The Anatolian peninsula which comprises the great bulk of Turkey’s territory has been home to some of mankind’s earliest settlements dating back to 10,000 BC. Over the millennia Anatolia’s rich geography and varied climate have attracted numerous peoples and spawned many civilizations and empires. These peoples range from prehistoric man, the Hittites, Seljuks, Lydians, Phrygians, and Trojans, up to 1 Research on this paper was partially subvented by the Turkish Cultural Foundation, Washington DC. Arnold Reisman received his BS, MS, and PhD degrees in engineering from UCLA. He is a registered Professional Engineer in California, Wisconsin, and Ohio, and has published over 300 papers in refereed journals, along with 16 books. After 27 years as Professor of Operations Research at CWRU, Reisman retired in 1994. Among his current research interests is the history of German-speaking exiled professors starting in 1933 and their impact on science in general and Turkish universities in particular. Reisman is still actively pursuing his lifelong interest in sculpting. He is listed in Who's Who in America, Who's Who in the World, American Men and Women of Science, and Two Thousand Notable Americans, and he is a Fellow of the American Association for the Advancement of Science. His most recently published book is: TURKEY'S MODERNIZATION: Refugees from Nazism and Atatürk’s Vision. Two other books are due out toward the latter part of 2008. They are: Classical European music and opera: The case of Post-Ottoman Turkey, and Arts in Turkey: How ancient became contemporary. 2 1 and including the Ottomans. The Hittites and the Seljuks left artiacts documenting thriving arts cultures which included sculpture depicting animals and the human figure. Sculptures at Nemrut mountain, (69–34 B.C.), Adıyaman, Turkey, Photo by Sezgin Aytuna This paper is about a nation’s journey of cultural transformation, a process undertaken by the Republic of Turkey soon after gaining its independence in 1923. Mustafa Kemal Atatürk (1881-1938), Turkey’s acknowledged father, and first president, envisioned a process which is still ongoing. There is no certainty as to the conclusion of the journey but to date the progress has been monumental and mostly irreversible. Atatürk’s objective was the modernization and westernization of Turkey’s culture as it pertained to the country’s nation-building agenda. Provided are little known insights dealing with the visual arts and their impact - a vital and under-stressed aspect of European cultural imperialism that was willingly accepted and in fact invited into the young republic. Religion and culture When Islam spread across the region during the eighth and ninth centuries the art of sculpting went into hibernation and lay dormant for several centuries because the values and rules of the religion. During most of the years of the Ottoman rule, depiction of the human figure in any form was frowned upon if not totally prohibited. There was no tradition of fine arts as they had developed in the West. As far as public sculpture is concerned, the first installations did not appear until after 1923, after the Ottomans’ demise in the wake of WWI and when, from the Empire’s ashes, the Republic of Turkey was founded. Many monuments depicting Turkey’s formation as a Republic and its founders were commissioned using German and Austrian sculptors. These statues were installed in the major cities such as 2 Istanbul, Izmir and the country’s emerging capital Ankara. They also appeared in the country’s heartland regional (town) centers such as Konya and Isparta. Fine arts Painting, a fine art as it is known in the West, was introduced earlier than sculpture. More easily acceptable, it grew and developed as an art form. During the nineteenth century, members of the aristocracy, diplomatic, and military hierarchy of Ottoman society began questioning the reasons for the Empire’s backwardness when compared to the West. The concept that to be at the same level of cultural, social, economic, scientific, and military development as the West it would be necessary to adopt its “ideas and technological abilities” gave rise to the Tanzimat Edict of 1839.3 This move toward westernization began with Sultan (1789 to 1807) Selim III and continued with Sultan (1808-1839) Mahmut II. Unlike previous attempts at westernization ,the modernization that ensued did not fixate on the military. The Tanzamit Edict opened the gates allowing representational art into society.4 However, at first,the artists working in this new genre merely painted the court in all its finery. 3 The Gülhane Edict of 1839 is the first rights (in the western sense) document within Ottoman-Turkish constitutional history. It is also known as the Tanzimat Fermani Edict. In 1856, the Islahat Fermani Edict reinforced these rights. “The first Ottoman-Turkish constitution in Turkish history is the 1876 Constitution known as Kununu Esasi,or fundamental law, adopted on December 23.” Although it still reserved “a vast array of rights to the Sultan who actually had no burden of accountability … it instituted a Parliament with Upper and Lower Chambers (Meclisi Ayan and Meclisi Mebusan)” Following the Tipoli and the Balkan wars, changes which increased the Sultan’s power, including the right to dissolve the Assembly, were made in 1914. In 1921, a new constitution was ratified by the National Assembly only to be abrogated by the General Assembly along with all of the Ottoman edicts by the first republican-period constitution on April 20, 1924. Mustafa Kocak and Fuat Andic, “Governance and the Turkish Constitutions: Past and Future.” (2008) Working paper. The Gülhane Edict was proclaimed on the grounds called Gülhane (House of Roses) of the Topkapı Palace on November 22, 1838. Now, it is a public park bearing the same name and located next to the Istanbul Archeological Museum. 4 During the Tanzimat period, books were being translated and fine art including photographs of the human figure was introduced into the empire. 3 Commander of the Ground Forces, Foreign Minister, Minister Responsible for all Matters Connected With Law and Religion, Head of the Suite of the Minister of Justice Many artists who had been trained in illustration at the military academies went abroad to further their education and learn new techniques. The representational art that emerged were illustrations both in style and subject matter. Most paintings showed specific citizens who held positions in their communities and how they dressed. Other paintings depicted Ottoman officials in their uniforms, while others showed individuals within the context of landscapes. In terms of European art standards of the times, these works had a naiveté about them. However more significant change in the style and substance of painting began in the late nineteenth century when a handful of Turkish painters (in the western sense) emerged on the Ottoman fine arts scene. Among them were Osman Hamdi Bey (1842-1910) and Şeker Ahmet Paşa (1841-1907), Both men produced art that is still highly valued by art historians and by Ottomanists alike. Hamdi’s “Tortoise Trainer” and Şeker Paşa’s “Still Life” are good examples of their respective work. 4 “Tortoise Trainer” painting is on display at the Pera Museum in İstanbul Still Life, Şeker Ahmet Ali Paşa Oil on Canvas, 89x130cm, Museum of Fine Arts, Ankara Sculpture, however, took longer to enter the Ottoman world. The average citizen had a difficult time accepting it. Perhaps two- dimensional art such as painting was not a threat as was sculpture. The representation of the human figure, prohibited by Islam, was not “real” when it was a flat figure on a canvas. However a sculpture, a three dimensional work showing depth and accuracy, was more than most people could tolerate. Sculpture was too great a departure from Islamic tradition and they were not ready to accept it. And public sculpture such as monuments was out of the question. 5 During the Tanzimat period, several attempts were made to create public monuments. An Italian sculptor Gaspare Fossati (1809-1883) was commissioned to design a monument with the entire text of Gülhane Hatt-ı Şerifi5 engraved on it. It was to be placed in Bayezid Square, close to the entrance of the Istanbul Dar-ül Fünun (house of knowledge), a fledgling state university which eventually became the University of Istanbul. The project was never realized6 because of religious considerations. Another Tanzimat era monument was designed by Artin Bilezikçi, a Turkish architect educated in Paris, and was exhibited in the 1855 World Exposition in Paris, but this, too, was not accepted by the public for the same reasons. Western Classical Music during the Ottoman Empire According to musicologist Kathryn Woodard7 who explored the music of Asia, a mostly unknown entity in Western countries,8 “Western music made its way to Turkey, as a substitute ….for the Janissary music that Europeans had come to associate with the Ottoman Empire.9 This turn of events was the result of Sultan Mahmud II’s (1785-1839) decision in 1826 to abolish the Janissary corps after decades of previous attempts by his predecessors to reform the Ottoman army met with little success. Mahmud’s goal was to form a new army along European lines and as part of the break from the past he substituted a European military band to replace the music of the Janissary corps.” Woodard states “because of his military career and training in music, Giuseppe, (17881856) brother of the opera composer Gaetano, [Donizetti]” was invited to Istanbul to help with the musical aspects of the military’s reforms. Donizetti composed marches and directed the army’s first regimental band. The Mahmudiye for Sultan (1730–54), Mahmud I was composed in 1829 soon after Giuseppe’s arrival, and the Mecidiye was dedicated to Sultan Abdülmecid Mahmud’s successor in 1839. “Donizetti also formed 5 6 Proclaimed on 22 November 1838. Günsel Renda, "Osmanlılarda Heykel", Sanat Dünyamız, N.82 (2002 winter), p.140. Kathryn Woodard, “Western Music in Turkey from the Nineteenth Century to the Present” http://www.newmusicon.org/v11n1/v111turkey.html 7 8 Kathryn Woodard, "Creating a National Music in Turkey: The Solo Piano Works of Ahmed Adnan Saygun," D.M.A. Thesis, University of Cincinnati, 1999. “The Turkish military band, or mehter, was originally used in the Ottoman Empire’s special military force, the janissaries. First appearing in Europe in 17th-century Polish and Russian courts, the mehter introduced a sound that was heavy on drums, cymbals, and horns. European composers sought to imitate the percussive and shrill qualities of mehter music, giving rise to what is sometimes referred to as the alla turca style. Alla turca music included a march-like rhythm, dynamic contrasts, simple harmonies, and novel percussion instruments (tambourine, triangle, cymbals), with piccolos evoking the shrill Turkish horns. Keys of F, B-flat, D, and C were common in alla turca music, being the easiest keys for the wind instruments to play.” http://www.blo.org/season_abduction_turkish.html 9 6 and directed an Imperial orchestra that performed at the Ottoman palace …for the Sultan’s European guests. In 1836 he assisted in establishing the Imperial Music School (Muzika-i Hümayun Mektebi) for the training of the palace musicians,” and invited other Europeans to teach there. Instruction was also provided to some of the female residents of the harem and the “harem had its own orchestra that performed at court functions.” Leyla Saz (1850-1936), or Leyla Hanimefendi was one of the most prominent musicians educated in the harem. “Her memoirs provide a unique glimpse at the musical life of the nineteenth-century Ottoman palace.” “Saz is recognized as one of the foremost composers of Ottoman classical songs, or şarkı, of the nineteenth century. She also composed marches in the European style.”10 In her memoirs Saz described how Turkish and Western music existed side by side in the palace: “The orchestra for Western music and the brass band practiced together twice weekly and the orchestra for Turkish music only once.… Western music was taught with notes and Turkish music without them; as had always been the custom, Turkish music was learned by ear alone.”11 By the middle of the 19th century performances of Western music were no longer restricted to the Ottoman palace. The elite were introduced to music from Europe by traveling opera companies and performances by solo virtuosos such as Franz Liszt (18111886) who visited Istanbul in 1847. Many performances were offered as a matter of public relations by foreign embassies. “Italian operas were particularly popular at this time, and full productions of Verdi’s [1813 -1901] IL Trovatore, Un Ballo in Maschera, and Rigoletto were performed at the Naum Theatre soon after their European premieres.”12 At least four European operas had an Ottoman setting or motif.13 Opera and the Ottomans European ambassadors to the Sultanate frequently mentioned “opera” in their conversations at embassy and palace functions and Ottoman ambassadors to European countries filed reports in which operas were detailed. As interest in all things Western grew so did interest in opera. “The first musical play to be staged at the palace was during 10 Leyla (Saz) Hanimefendi, The Imperial Harem of the Sultan: The Memoirs of Leyla Hanimefendi, Reprinted by Hil Yayin, Istanbul, 1998. 11 Ibid 12 Mahmut R. Gazimihal, Türk Avrupa Musiki Münasebetleri, Ankara, 1939. Wolfgang Amadeus Mozart’s (1756 - 1791) Abduction from the Seraglio (Die Entführung aus dem Serail); George Frideric Handel’s (1685-1759) Tamerlano (Tamerlane); Gioachino Rossini’s (1792-1868) Il Turco in Italia and a counter point in L’Italiana in Algieri. Moreover, Mozart's fascination with the Ottomans is reflected in his Violin Concerto no. 5, known as The Turkish, and the famous last movement of a piano Sonata a la Turca. 13 7 the reign of Murat III (1574-1595). Sultan Selim III (1761-1808), who was also a composer, invited a foreign company to stage an opera at Topkapi Palace in 1797.” 14 ‘Ernani’ by Giuseppe Verdi was performed by an Italian company in the Beyoglu section of European Istanbul in 1846. Gaetano Donizetti’s “Belisario” was the first opera to be translated into Turkish, and was performed in 1840 “at the first theatre built by the Italian architect Bosco.” In 1844, that theater was transferred to Tütüncüoglu Michael Naum Efendi who provided theater performances to the citizens of Istanbul for 26 years. The first opera performed at the Naum Efendi Theatre was Gaetano Donizetti’s “Lucrezia Borgia” in 1844. The theatre burned down in 1846, and Naum Efendi built a new one where Tokatliyan Ishani stands today. Because of the second fire at Michael Naum’s theatre on June 5, 1870 and the Empire’s continual years of political turmoil, opera became less important. until it vanished from the entertainment scene. For 38 years, from 1885 to 1923, “Turkish polyphonic music and opera were unable to develop and lay dormant.”15 Discussion The rejection of Ottoman culture, and the quest for its replacement was an integral part of the republican ideology starting in 1923. To be sure a few German and Austrian sculptors were invited to design monuments to the Republic within a year of its founding. However full implementation of the reforms was not possible as local talent was insufficient for doing that until a window of opportunity presented itself in 1933. The creation of educational and cultural institutions based on Western models and the role and influence of foreign experts who were invited to Turkey to develop and run educational and cultural institutions is one of the most significant phenomena of Westernizing policies in the cultural field.16 Developments in Germany on the eve of the Second World War gave the Turkish government this opportunity. In 1933, the Nazis’ plans to rid themselves of Jews beginning with intellectuals with Jewish roots or spouses became a windfall for Atatürk’s determination to modernize Turkey. A select group of Germans and later Austrians with a record of leading-edge contributions to their respective disciplines were invited,17 with the Reichstag’s understanding, to transform Turkey’s system of higher education and the new Turkish 14 http://www.ualr.edu/mxsarimollao/turkiye/Art&Culture_4.htm#0 Ibid 16 Berk 2004, p.118. 17 Albert Einstein himself was played a role albeit small in brokering the Turkish government’s invitations for the persecuted intellectuals. See Arnold Reisman, 2007a, 253-281. 15 8 state’s entire infrastructure.18 This arrangement, occurring before the activation of death camps, served the Nazis’ aim of making their universities, professions, humanities, and their arts Judenrein, cleansed of Jewish influence and free from intelligentsia opposed to fascism. Because the Turks needed the help, Germany could use this situation as an exploitable chit on issues of Turkey’s neutrality during wartime.19 Thus, the national selfserving policies of two disparate governments served humanity’s ends during the darkest years of the 20th century. The invitation saved the lives of over 190 eminent intellectuals,20 their families, and some staff members. Paul Hindemith(1895 –1963), Carl Ebert (1887-1980), Eduard Zuckmayer (1890-1972), Ernst Praetorius (1880-1946), Licco Amar (1891-1959), and over a score of musicologists and performing artists were among them. Carl Ebert and Paul Hindemith were responsible for bringing classical music and western theater including opera to Turkey. Ebert was responsible for the institutionalization of opera in Ankara and Istanbul. While his story as theatrical producer, popular opera director, entrepreneur, innovator, educator, and manager is fairly well documented, his role of institutionalizing opera in Turkey is dimly lit and largely unknown by western historians. Because of the Nazi racist laws, the vast majority of the émigrés had their German passports taken away while in Turkey, making them what the Turks deemed as Haymatloz or stateless. Transcending Turkey’s development, this short term diaspora was also of monumental consequence to the global history and philosophy of science, the arts and the humanities. Yet this story has been barely noticed by western historians for over 70 years.21 This included consultancy on the drafting of all civil laws and of a commercial code. See Fuat Andıç and Arnold Reisman, 2007. 19 The Bosporus and the Dardanelles held strategic importance. So did an uninterrupted supply of chromium and other scarce materials needed by Germany’s munitions factories. This strategic importance was sufficient for the Reich to release dentistry professor Alfred Kantorowicz from nine months of incarceration in concentration camps because Turkey needed his expertise. See Arnold Reisman 2007b, pp. 1-13. 20 Some of the émigrés served as conduits of communication between colleagues, friends, and relatives left behind and others in the free world. It is a great fortune from a historical perspective that some of this correspondence was preserved for posterity. See Arnold Reisman, 2007c, pp. 450-478. 21 Frederick W. Frey, 1964, pp. 205-235 represented work commissioned by the Social Science Research Council under a grant from the Ford Foundation. In the thirty- [30] page highly documented chapter discussing “Education in Turkey,” which includes higher education from the days of the Ottomans through the 1950s, Frederick W. Frey, a Princeton PhD, Rhodes Scholar, the author by then of Turkish Political Elite, a professor at MIT and “member of the senior staff of its Center for International Studies” never mentioned anything whatsoever about the role played by the German émigré professors in the evolution of Turkish higher education. Nor is this major infusion of the best western knowledge into Turkish society mentioned anywhere else in this 500-page volume. Moreover, in May 1991, an international and interdisciplinary group of scholars convened at the Wissenschaftskolleg in Berlin to discuss the impact of forced emigration of German-speaking scholars and scientists after the Nazi takeover in 1933. (Mitchell G Ash and Alfons Söllner 1996). The result of that conference is the cited and referenced book. In its Foreword, Donald Fleming critically reflects on the established historical paradigm, e.g., “Germany had been intellectually punished for yielding to the Nazis and America and Britain intellectually rewarded for their political and civic virtues.” Significantly, the book’s (10-page, double-column, small-print) Index has 18 9 The Reform of the system of higher education had always been high on the agenda of the new Turkish Republic. In 1932, Professor Albert Malche (1876-1956) had been invited from Switzerland to examine the Darülfünun and other institutions of higher education. His Rapport sur l’université d’Istanbul was submitted on May 29, 1932. Less than a year later, Hungarian-born Frankfurt pathologist Dr. Philipp Schwarz (1894–1977), among the first of those dismissed from their posts by the Nazis, fled with his family to Switzerland. Malche, recognizing a double opportunity to save lives while helping Turkey, contacted Schwarz and in March 1933, Schwarz established the Notgemeinschaft Deutscher Wissenschaftler im Ausland (Emergency Assistance Organization for German Scientists) to help persecuted German scholars secure employment in countries willing to receive them.22 Predisposed to German science and culture and recognizing the opportunity that presented itself, Turkey invited Philipp Schwarz to Ankara based on Albert Malche’s recommendation.23 To their meeting on July 5, 1933, Schwarz brought with him the resumés of the members of the Notgemeinschaft,24 while Turkish Minister of Education Reşit Galip (1893–1934) arrived with a complete list of the vacant professorships at Istanbul University. Their mission was to select individuals with the highest academic credentials in disciplines and professions most needed in Turkey. After nine hours of negotiations, agreement was reached on candidates for the Istanbul professorships, 33 in number, all of them members of the Notgemeinschaft.25 Even though it had forced the dismissal of all the candidates, all the appointments still had to be approved by the Nazi government, for they still had power over their citizens and could have refused them permission to leave. It must be emphasized that it was clearly understood from the outset that the German professors would stay in Turkey only until their Turkish pupils could only one entry for Turkey. Page 10 mentions Turkey along with Palestine and Latin America in reference to studies documenting problems encountered by émigré academics. This and more is documented in (Arnold Reisman, 2008) Hence, the above “dim-lit and largely unknown” claim. 22 Neumark noted that three revolutions came together to make the 1933 “miracle” happen in Turkey: the Russian revolution in 1905, the Turkish revolution in 1923, and the Nazi takeover in 1933 (Zuflucht am Bosporus, p. 13). 23 P. Schwarz, Notgemeinschaft Zur Emigration deutscher Wissenschaftler nach 1933 in die Türkei (Marburg: Metropolis-Verlag, 1995); the organizer of the Notgemeinschaft lost his sister and her entire family in German gas chambers. 24 For details see A. Reisman Turkey's Modernization: Refugees from Nazism and Atatürk's Vision. Washington, DC: New Academia Publishers, 2006 pp 8-10, 25 On February 1, 1934, Dr. Karl Brandt (1899–1975), the administrator of the Notgemeinschaft, wrote from New York: “Den ersten großen Erfolg erzielte die Notgemeinschaft in den Verhandlungen mit der türkischen Regierung, bei der sie durchsetzte, dass 33 deutsche Professoren an die Universität Istanbul berufen wurden. Über die Berufung einer größeren Zahl deutscher Privatdozenten eben dorthin schweben aussichtsreiche Verhandlungen.” In a confidential circular letter containing the Annual Report for 1935–36 (undated), the Notgemeinschaft reported having secured further 8 “stable” (for the contract period) positions for scientists in Turkey. There are copies of both documents in the Albert Einstein Archives, Jewish and National University Library, Jerusalem. 10 take over. Five-year contracts were the rule. Courses were to be taught in Turkish as soon as possible, using textbooks that had been translated into Turkish.26 As an institution The Darülfünun was accused by the Ministry of Education of having lagged behind the “revolution” and its faculty was accused of being backward in scholarship. Some of these academics had also criticized a few ideas and decisions made by the first Turkish Historical Congress in 1932. In a speech delivered in that year to the Turkish Grand National Assembly, Reşit Galip, the Minister of Education said the following: In the eight years between 1923 and 1932, the gaze of the entire Turkish élite has been turned towards the Darülfünun... No other national concern attracted us as much attention as the Darülfünun issue. No other institution received as much criticism. Yet despite all this attention and criticism, the Istanbul Darülfünun has failed to show the anticipated betterment, progress or advancement. There have been momentous economic and social reforms in the country. Darülfünun has remained a noncomittal observer. There were important new economic trends. Darülfünun appeared unaware of these. There were radical changes in the legal system. Darülfünun contented itself with merely including the new laws in its instruction programme. There was the alphabet reform. There was the new language movement. Darülfünun never heeded them. A new understanding of history swept the entire country as a national movement. It took three years of waiting and effort to elicit Darülfünun’s interest. The Istanbul Darülfünun has become static; turned into itself; withdrawn from the external world in complaisant isolation.”27 Darül Elhan (House of Music) in Istanbul had already experienced a similar change in 1926 when its name was changed to Konservatuvar. Not only the name, but also the structure of the municipal conservatoire was changed giving more emphasis to Western music. The department of Eastern music closed in 1927. With the goal of the establishment of a state conservatory in Ankara, Halil Bedii (Yönetken)28 and Nurullah Şevket (Taşkıran) were sent to Europe for advanced musical education in 1926. Ulvi Cemal (Erkin)29, Cezmi (Erinç), Ekrem Zeki (Ün) and Afife Hanım were in a second group of students who went to European cities for their musical education.30 The 26 Müller, H (1998). German Librarians in Exile in Turkey, 1933-1945. Libraries & Culture, 33, (3) 294305 27 Ayşe Öncü, ‘Academics: The West in the Discourse of University Reform’, in Turkey and the West: Changing Political and Cultural Identities, ed. by Metin Heper, Ayşe Öncü and Heinz Kramer (London & New York: I.B. Tauris, 1993), pp. 142-76 (pp. 142-43). 28 The names given in brackets are the family names adopted by all Turkish citizens following the law passed on 28 June 1934. 29 Erkin (1906-1972) belonged to the group called Beşler (The Five), together with Cemal Reşit Rey (19041985), Ferit Alnar (1906-1978), Ahmet Adnan Saygun (1907-1991) and Necil Kâzım Akses (1908-1999) who were the pioneering composers in Turkish polyphonic music. 30 With the Law no. 1416 (Law Regarding Students to be Sent to Foreign Countries), enacted in 1929, the Ministry of National Education started sending students abroad every year to receive undergraduate and graduate education with formal scholarships in order to meet the instructor requirements of universities and 11 government assumed financial responsibility for Cevat Memduh (Altar) and Necil Kâzım (Akses) who were already studying in Europe. During the 1930s Necdet Remzi (Atak), Ferhunde (Erkin), Ahmet Adnan (Saygun) joined these students. The new building for the conservatory was built in 1928 by Ernst Egli (1893–1974) a Swiss architect who came to Turkey in 1927 at the invitation of the Turkish government. The University Act of 1933 was passed with the intentions of changing the traditional educational system and dismissing all of the personnel who represented that system.31 Malche’s report detailing his investigations was the main source on which the 1933 reform on education was based.32 The day after Darülfünun’s closure, Istanbul University was opened, using Dar-ül Fünun’s physical plant; the faculty consisted of a few members of the former faculty, augmented by more than thirty world-renowned émigré German professors who were en route to Turkey. Most of the new senior faculty were given the title Ordinarius Professor (“Ord. Prof.”).33 The contracts were individual and for fixed terms, although renewable; they did not include any pension rights. By October 25, 1933, the first invitees began arriving in Istanbul.34 At the opening of the university, Dr. Reşit Galip (-1934), Minister of Education and one of the leaders of the reform emphasized the turning of a new page in university life with these words: We decided that the most suitable and radical solution to ensure our aims was to maintain the number of foreign professors as high as possible: To raise our new educational institution to a high level in the shortest time, to minimize the phases of establishment, development and improvement, to rapidly train young Turkish scientists near able leaders and finally to organize scientifically the laboratories, seminars and teaching in its most general sense and to make certain that a new road is paved to original the requirements of other institutions and organizations for qualified personnel educated abroad. This way, students of many different fields of study, from Natural Sciences to Fine Arts and Archeology, obtained the chance to study abroad. See Kansu Şarman, Türk Promethe’ler: Cumhuriyet’in Öğrencileri Avrupa’da [Turkish Promethes: Students of the Republic Are in Europe] (İstanbul: İş Bankası Kültür Yayınları, 2005). 31 Öncü says that roughly a third of the teacher cadres were dismissed whereas Katoğlu gives the number as 157 out of 240. 32 See Albert Malche, ‘İstanbul Üniversitesi Hakkında Rapor’, in Dünya Üniversiteleri ve Türkiye’de Üniversitelerin Gelişmesi, ed. by Ernest E. Hirsch (Istanbul: Ankara Üniversitesi Yayınları, 1950), pp. 22995. 33 At that time, ordinarius professors brought in from foreign countries were paid 600 liras a month; other professors received half that. For comparison: during the same period, the prime minister’s salary was 500 liras. See K. Şarman, Türk Promethe’ler, Cumhuriyet’in Öğrencileri Avrupa’da (1925–1945) (Turkish Prometheuses: Students of the republic in Europe [1925–1945]) (Istanbul: Türkiye İş Bankası Kültür Yayınları, 2005), 154. 34 Fewer of the academics found their way to Ankara than to Istanbul, because in 1933 Ankara University existed primarily on paper. Unlike those émigrés who came to the University of Istanbul under the auspices of the Notgemeinschaft, most of the scientists, architects, and artists who went to Ankara were invited through the German and Austrian legations; the largest share of them went to the state school of music, the faculty of arts, and the medical institutes. The correspondence found in several worldwide archives involves only members of the Istanbul contingent. 12 research in all faculties while ensuring the establishment of an authentic university spirit and understanding.35 In the catalogue for an exhibition held to honor the memories of the emigre professors and their legacies, held in Istanbul during 2007, professor Murat Katoğlu wrote36: It has become customary and habitual to designate in general the collective change of locale of scholars, artists, experts, researchers and technicians who were “transported” from Germany to Turkey in 1933 and the following years by words such as “seeking refuge, refugees, asylum seekers” both in Germany and in Turkey. However, these words or expressions suffice to describe neither the extraordinary change in the life of these people nor Turkey’s approach to this subject.....[They] do not explain the essence of this very special event. 37 As far as the German intellectuals were concerned, they did not leave their countries for Turkey as refugees, a term they abhored.They had signed contracts ensuring employment, remuneration and even security of life as a result of invitations by the official organs of the state.38 In 1935, composer Paul Hindemith (1895-1963) was invited as a consultant to assist in the creation of the conservatory and for the establishment of a musical culture in Turkey.. During the following years Hindemith made many visits to Turkey and he was present at the first entrance examination given to the students in 1936 as were Eduard Zuckmayer (1890-1972) and Dr. Ernst Praetorius (1880-1946), the conductor of a newly created orchestra.39 Carl Ebert who came to Turkey in 1936, created a school of performing arts within the conservatory.. After centuries of dormancy, Turkey’s other visual and three dimensional arts began to awaken and flourish during Atatuk’s Presidency and have been enlarging in scope ever 35 Hirsch, E .E. (1982). Aus des Kaisers Zeiten durch die Weimarer Republik in das Land Atatürks. Eine unzeitgemäße Autobiographie. J. Schweitzer, Munich 36 Murat Katoğlu, “Were German scientists and experts refugees?” Haymatloz – Özgürlüğe giden yol”, Milli Reassürans T.A.Ş., Istanbul, May 2007. 37 Ibid. 38 This migration typology can be succinctly described as having the following attributes: It was CROSSCULTURE, CROSS-BORDER, and indeed CROSS-REGION. It was a FORCED MIGRATION having elements of a CHAIN MIGRATION with an established linkage or chain from the point of origin for migrants to their destination. Friends and relatives already transplanted enable the migration of others by providing them information, money, and place to stay, perhaps a job, and emotional support. As will be shown there was an unusual component of FAMILIAL MIGRATION as the result of a degree of nepotism. Clearly it was BY-INVITATION-ONLY MIGRATION INTELLECTUAL MIGRATION involving much TRANSFER OF KNOWLEDGE AND OR TECHNOLOGY. It is an understatement to say that both PUSH FACTORS and PULL FACTORS were involved AND THE MIGRATION resulted in a significant BRAINDRAIN for the Axis countries while ending up as a BRAIN-GAIN to the host countries, Turkey first, and the US, post-war Germany and the State of Israel. 39 For the German musicians in Turkey, see Cornelia Zimmermann-Kalyoncu, Deutsche Musiker in der Türkei im 20. Jahrhundert (Frankfurt am Main: Peter Lang, 1985). 13 since. Ironically as these arts began to flourish, calligraphy, an old and respected art form, was considered a hold over from the religius Ottoman era, and was soon ignored and rejected Represenational sculpture went on public display within the first decade of the Republican era. However since there were no indigenous sculptors, the first monuments were designed by foreigners, mostly Germans, though some like Pietro Canonica (1869 – 1959) had Turkish art students assisting them. Classical Western music, opera , ballet,and the theater enjoyed impressive strides. Architecture gained new vigor and many museums were opened. Several hundred “People’s Houses” and the ” People’s Rooms” through out Turkey gave the locals including youngsters a wide variety of artistic activities, sports, and other cultural affairs. Book and magazine publications enjoyed a boom. The film industry started to grow. In all walks of cultural life, Atatürk’s inspiration created an upsurge. In only eight decades public sculpture,previously unheard of anywhere in Turkey, is now everywhere. During the 85 year period, the city of Ankara alone accumulated over 250 significant outdoor istallations.40 Most of them depict the human figure or other living creatures. Hitit Güneşi, ’Hittite Sun' Symbol of Ankara by Nusret SUMAN, 1978, Photo by Salih SAYDAM, May 17, 2008 40 Umut Erhan, MD and Haldun Cezayirlioðglu, http://www.kentheykelleri.com/ personal communication 26 February 2008. 14 Homunculus, Küçük Adam, 1993, Fiberglass, “Feza Gürsey Science Center” Feza Gürsey Bilim Merkezi. Ankara.41 Photo by Salih SAYDAM, May 17, 2008 Turkey now has several world-class arts academies in addition to over 100 public and private universities42, each with a Faculty or some other adimintrative unit dedicated to fine art and sculpting. Its graduates contribute to arts comunities worldwide. Cultural life has witnessed continuous progress throughout Turkish society. In the visual arts development has attained a fairly high level of maturity. Turkish painters and sculptors exhibit at home and abroad, participating in many international festivals and receiving commissions all over the world. Starting with the republican Turkey’s early deacdes its commercial banking industry has assumed part of the responsibility of promoting the arts. Several privately founded museums with important collections display indigenous as well as foreign art. It is imposible to partake of all the cultural offerings in Istanbul at any given time. One can only manage a fraction of what is available. Classical western music and Opera in Turkey today 41 All indications lead one to assume that the mold for this sculpture was created at the Ontario Science Centre based on the research of Dr. Wilder Penfield, an eminent neurosurgeon and shipped to Ankara. Valerie Hatten, Librarian, Ontario Science Centre. Personal communication July 21, 2008. 42 According to Webometrics (www.webometrics.info/index.html) in 2008, the following Turkish universities ranked in the top ten percent among 5000 in the world, ODTÜ 390, Boğaziçi 455, Bilkent 489, İTÜ 754, Ankara. 808, Hacettepe 846, Ege 936, Gazi 988. www.webometrics. info/top4000.asp, www.webometrics.info/top500_europe.asp 15 Public funds are also used to provide partial support for private theater groups and for major art exhibits and festivals. Because Turkey was an area where ancient civilizations developed and was a significant crossroad for other civilizations, the country boasts a number of archeological amphitheaters that are still used for performances during mild weather. Among them are: Ancient concert hall of Troy Ephesus amphitheater, seating capacity of 15,000. Photo by Sezgin Aytuna, 2007 43 Ancient theater of Aspendos, 2nd C. D. Photo by Sezgin Aytuna, 200644 Aspendos is a showcase for the best productions from all five Turkish opera houses (the other venues are located in Ankara, Izmir, Antalya and Mersin). Over time these 43 44 www.sezgin-aytuna.com, Courtesy Sezgin Aytuna, Ibid 16 festivals have included performances from abroad, for example Eugene Onegin with Valery Gergiev and the Deutsche Opera Berlin’s production of The Magic Flute.45 However the Atatürk Cultural Center Atatürk Kültür Merkezi (AKM) a multi-purpose cultural center located in Taksim Square of İstanbul, is a popular facility. Atatürk Cultural Center Atatürk Kültür Merkezi, Taksim Square, Istanbul The complex includes the "Grand Stage", a hall with a 1,307 seat capacity which hosts performances of the Turkish State Theatres and the Turkish State Opera and Ballet. It also has the "Concert Hall", with a capacity of 502 seats for concerts, meetings and conferences as well as an exhibition hall of 1,200 m² located at the entrance. Also in the complex is the "Chamber Theatre" with 296 seats, "Aziz Nesin Stage" with 190 seats and a cinema hall having 206 seats. The Center is home to the Istanbul State Symphony Orchestra and Choir (İstanbul Devlet Senfoni Orkestrası ve Korosu), Istanbul State Modern Folk Music Ensemble (İstanbul Devlet Modern Halk Müziği Topluluğu) and Istanbul State Classical Turkish Music Choir (İstanbul Devlet Klasik Türk Müziği Korosu). During the summer AKM hosts the Istanbul Arts and Culture Festival. The current complex replaced the former AKM which was destroyed by fire on November 27, 1970. Model of the original Atatürk Kültür Merkezi (AKM) designed by émigré architect Clemens Holzmeister and Carl Ebert. 45 Diana Ross gave a live concert in 1997. Courtesy Sezgin Aytuna, 17 Turkey’s annual international music festivals46 The first Music Festival in Istanbul took place during June and July of 1973 and achieved such unanimous acclaim that it became an annual event. From the outset, the Istanbul Festival included the very best in music (orchestral concerts, chamber music, recitals, and traditional Turkish music), classical ballet, contemporary dance, opera, folklore, jazz/pop, cinema, drama and visual arts from the world at large. It also offered a program of seminars, conferences and lectures. A change in name was needed in 1986 after the Biennial, Film, Theater and Jazz segments of the festival grew into their own distinct festivals.. The International Istanbul Festival became known as the International Istanbul Music Festival. This festival became a summer festival of classical music, ballet, opera and traditional music. In its programs, the Festival emphasizes “sharing artistic inspiration” where international orchestras and conductors perform with Turkish soloists or vice versa. The BBC Symphony Orchestra conducted by Adam Fisher with soloist Idil Biret; Czech Philharmonic Orchestra conducted by Vladimir Valek with pianist Fazil Say; Istanbul State Symphony Orchestra conducted by Gotthold Lessing with soloists Suna Kan, Ayla Erduran and Yehudi Menuhin; Montserrat Caballé with Istanbul State Opera and Ballet Orchestra and Chorus conducted by José Collado; and Symphonieorchester des Bayerischen Rundfunks conducted by Lorin Maazel with pianist Hüseyin Sermet are results of this approach. The International Istanbul Music Festival, the flagship of all International Istanbul Festivals, has earned a reputation for its significant role in encouraging research in musicology as well as launching special projects on shared cultural values through its productions. By 2007 the International Istanbul Music Festival had celebrated its 35th anniversary. This was a reason to combine what is known as “event tourism” with “cultural tourism.” However because some of the events took place in the Rumelihisari (Rumeli Fortress), Rumeli Fortress viewed from the Bosphorus built in only four months by Sultan Mehmet the Conqueror in 1452 in preparation for the final attack on Constantinople which lead to the downfall of the Byzantine Empire, the event provided elements of architectural interest. Archeological elements were introduced by having events held at the Anadoluhisari (Anatolian Fortress) 46 http://www.melodytrip.com/MTFestival/Default.aspx?FestivalID=998 18 Anadoluhisari (Anatolian Fortress) viewed from the Bosphorus a 14th century relic located on the Asian shore and the narrowest point of the Bosphorus. It was built to serve the Ottoman's first attempt at conquering Istanbul. Sultan Yildirim Bayezit built this fortress in 1393 on the ruins of a Roman temple dedicated to Zeus. The émigrés’ impact on Turkey and her culture can be seen any time there is an opera or a music festival. Today, operas are produced regularly in five Turkish cities thanks to Carl Ebert who helped realize one of Atatürk’s visions for his people. A Poster for a recent production of Donizetti’s Don Pasquale In her book Translation and Westernisation in Turkey, Ozlem Berk47 provides performance and attendance statistical data spanning a number of years. During the 1949 – 1950 State Theater season eleven different works were performed. Of these, ten were translations and the attendance totaled 70,235. The comperable figure for the 1971-1972 were 12 domestically written production and only one from abroad while the attendance rose to 389,019. During its 1940 - 1941 season the Istanbul Municipal Theater staged fifteen different performances of which four were original, five were translated and six 47 Ozlem Berk, Translation and Westernisation in Turkey, Istanbul: Ege, 2004, pp188 and189 19 were adaptations. The attendance for all performances was recorded at 217,639. Ten years later and during wartime in Europe, its performance mix included eight original works, six translations, and three adaptations with an attendance of 208, 904. By the 1970-1971 season its attendance had risen to 334, 906 for ten original and twelve translated works. The 2005-2006 season government statistics speak eloquently to the vibrancy of opera in Turkey. There were five opera and ballet halls operating in Turkey, having a total 3,860 seating capacity, one each in Ankara, Mersin, Mersin, Istanbul, and İzmir. They had 189 different performances of which 85 were domestic and 104 brought in from abroad with an attendance totaling 245,448.48 Fine Arts in Turkey today While the Turkish character in the output of contemporary Turkish artists is often unmistakable, it also represents a clear departure from the styles that dominated preRepublic paintings. There is no reason to search for the influence of specific Western innovations, because today, artists apply a creative fusion of old traditions and modern innovation. Many banks have their own private collections of historic and contemporary works. In 2004, Turkey opened its first museum of modern art privately funded by Bülent Eczacıbaşı, who according to Forbes magazine is Turkey's sixth-richest man49 and the key owner of Eczacıbaşı Holding. This Holding began as a pharmaceuticals distributor and is currently one of the handful of Turkish oligarchic family groupings.50 See Turkish statistical Institute’s “Culture statistics”, http://www.tuik.gov.tr/VeriBilgi.do?tb_id=15&ust_id=5. 48 49 50 <http://www.dexigner.com/forum/index.php?showtopic=564> Viewed December 23, 2005. Reisman (2005) 343 20 Museum of Paint & Culture"Modern Turk" 2001 Exhibition. Royal Stables of Topkapi Palace Museum, Istanbul Art Museum Translation and Performance Statistics European experts who were invited to Turkey, especially the German speaking émigrés, and translations from European sources, played a critical role in the establishment and development of western dramatic arts in Turkey. Despite the increased number of plays written by Turkish writers after the 1940s, the performances in the theatres were predominantly translations. Especially in the field of opera and ballet, almost all the works were Western since a handful of Turkish composers were still at the beginning of their careers.51 Over the years the number of theatre, opera and ballet halls, and the number of performances and attendance to the shows increased dramatically. The number of original and translated works seems more balanced than in earlier years. However, it should be added that translations still play a substantial role in the dramatic arts in Turkey: Province Total Ankara Antalya Mersin Istanbul Izmir Number of halls, seating capacities, shows, number of performances and attendance 2005-2006 Season52 Number of shows Number of Attendance performances Number Seating Total National Foreign National Foreign Total Citizens of opera capacity and ballet halls 5 3,860 189 85 104 268 263 245,448 89,540 1 723 96 55 41 86 90 58,529 31,671 1 802 10 2 8 5 15 7,312 1,406 1 638 24 10 14 32 35 20,268 8,797 1 1,304 27 12 15 125 44 121,780 40,871 1 393 32 6 26 20 79 37,559 6,795 Foreigners 155,908 26,858 5,906 11,471 80,909 30,764 According to the Turkish Statistical Institute in the same season, out of 608 total shows in all the 112 Turkish theatres, 448 were original works, whereas 160 were translations. The The first three Turkish operas, staged in the People’s House in Ankara in 1934, were Öz Soy and Taşbebek, and Bayönder, composed respectively by Ahmet Adnan Saygun and Necil Kâzım Akses. A second important event was the opening ceremony of the new opera and theatre house, converted from the Sergi Evi (Exhibition House) by the German architect Paul Bonatz (1877-1956) on 2 April 1948 where Cemal Reşit Rey’s first Symphony, Ulvi Cemal Erkin’s violin concerto, Necil Kâzım Akses’ Ballade and Ahmet Adnan Saygun’s lyrical drama, Kerem were for the first time performed. However, Saygun’s three acts’ Kerem could only be staged in the National Theatre in 1953. For the history of Turkish classical music, see Cevat Memduh Altar, Opera Tarihi, 4 vols. (Ankara: Kültür ve Turizm Bakanlığı, 1982). 52 See Turkish statistical Institute’s “Culture statistics” on http://www.tuik.gov.tr/VeriBilgi.do?tb_id=15&ust_id=5. 51 21 30 state theatres, on the other hand, staged 188 shows; 106 of which were original plays and 82 translations. The economy: Cultural tourism as an economic factor in Turkey The process which was started and nurtured as an integral part of public policy has, over time, reached a self sustaining stage both in the public and the private sectors, thus impacting its own evolution. Aided and abetted by various levels and agencies of government, the policy has resulted in Turkey’s social and economic development. According to the United Nations World Trade Organization (UNWTO) “Cultural tourism forms an important component of international tourism in our world today. It represents movements of people motivated by cultural intents, such as study tours, performing arts, festivals, cultural events, visits to sites and monuments, as well as travel for pilgrimages.”53 Cultural tourism is based on the mosaic of places, traditions, art forms, celebrations and experiences that portray a nation and its people. However, according to Myra P. Gunawan, as of 2004, “there is still doubt whether there is a common understanding between the scholars and the tourism business or among stakeholders of what [cultural] tourism is all about…..Literature on cultural tourism is not that much….The seemingly common term of cultural tourism is not a simple understanding, it has different meanings for different stakeholders.”54 “Two significant travel trends will dominate the tourism market in the next decade. Mass marketing is giving way to one-to-one marketing with travel being tailored to the interests of the individual consumer. A growing number of visitors are becoming special interest travelers who rank the arts, heritage and/or other cultural activities as one of the top five reasons for traveling. The combination of these two trends is being fueled by technology, through the proliferation of online services and tools, making it easier for the traveler to choose destinations and customize their itineraries based on their interests.” 55 Worldwide international arrivals are forecast by the UNWTO to top 1 billion by 2010 and over 1.6 billion in 2020.56 Turkey earned $18.6 billion from tourism in 2007, according 53 Cultural Tourism and Poverty Alleviation - The Asia-Pacific Perspective, Madrid, Spain, UNWTO, 2005 54 Myra P. Gunawan, Deputy Minister for Tourism, Ministry of Culture, and Tourism, Indonesia. Cultural Tourism and Poverty Alleviation - The Asia-Pacific Perspective, Madrid, Spain, UNWTO, 2005 p. 97. 55 National Assembly of State Arts Agencies, http://www.nasaa-arts.org/artworks/cultour.shtml Viewed August 23, 2008 56 Cultural Tourism and Poverty Alleviation - The Asia-Pacific Perspective, Madrid, Spain, UNWTO, 2005 p. 1. 22 to the World Tourism Organization (WTO) and tourism revenues are expected to total $19.5 billion in 2008. This translates to $2,760 on a per- capita basis.57 Turkey ranked 11th in terms of tourist arrivals and ninth in tourism revenues among the worlds' top 20 tourism destinations according to its State Planning Organization (DPT).58 According to ICOMOS the International Scientific Committee on Cultural Tourism: “Cultural tourism is that form of tourism whose object is, among other aims, the discovery of monuments and sites.”59 Cultural attractions played a major role. In recognition of culture as an economic factor in 2008 Akdeniz University hosted an “International Conference on Culture and Event Tourism: Issues & Debates.” This conference took place at the Belediye Kültür Merkezi in Alanya, Turkey. Although tourism departments or faculties focus more on the business side, many offer subjects or courses in cultural tourism as part of the folkloric studies or local studies. An example is: at Gazi University, “Folkloric or local studies include a one week “UNESCO approach to Cultural tourism.” Another example is Ankara University where the Faculty of Languages and History and Geography offer courses on local or folkloric studies. The Turkish expression for this is Halk Bilimi.60 According to a conference dedicated to new sociological research on technologies of government that was completed in the disciplines of architecture, planning, sociology, geography, and anthropology, then combined with studies on the production and consumption of culture through the fields of literature, art, and film: “Istanbul is one of many world cities that turn to culture to establish a place on the world map. It is also the site of a unique debate on European integration entwined with the memory of earlier Orientalist representations. The selection of Istanbul as one of the Cultural Capitals of Europe in 2010 highlights the social and spatial tensions of staging cities and imagining citizens as consumers of culture.”61 It is interesting to note that oil exporting and neighboring Iran’s total GNP per-capita is $1,750; in Iraq it is $1, 050; in Egypt it is $1,350; and non oil endowed Islamic countries such as Morocco $1,200; and Syria $970; 58 Anonymous “Turkey ranks high in tourism revenue” ANKARA - Anatolia News Agency April 16, 2008 57 59 ICOMOS International Scientific Committee on Cultural Tourism http://www.icomos.org/tourism/ Viewed August 23, 2008. 60 The author is grateful to Muhtesem Onder, Faculty Librarian, Özyeğin Üniversitesi, Istanbul for researching this issue. 61 ORIENTING ISTANBUL: CULTURAL CAPITAL OF EUROPE? an interdisciplinary conference. September 25-27, 2008, University of California Berkeley http://www.ced.berkeley.edu/istanbulconference/ 23 “Among the segments of tourism, cultural tourism stands out owing to its growth in popularity, which is faster than most other segments and certainly faster than the growth in tourism worldwide”62 “Using culture as a vehicle for sustainable tourism development is now becoming an important item in the priorities of public policy planners.”63 Concluding Remarks Turkey’s secular government was the driving force behind Atatürk ‘s program of modernization. Education has played a major role in the establishment of the varius fine arts comunities Thus Turkey is a country rich in its own national culture, open to the heritage of world civilization, and at home in the endowments of the modern technological age. The impact of the changes in visual arts is still felt in Turkish society and has relevance in current public policy debates worldwide. On a political level, the Republic’s struggle with its religious heritage has been ongoing over the decades and still continues. Yet, Turkey, a predominantly Moslem country, has displayed representational sculpture in cities and towns since the 1920s. Contrast this attitude to that of the Taliban in Afghanistan who, according to the Telegraph (UK) destroyed two of the largest and most ancient sculptures of Buddha because after 1500 years they had become offensive. The objectives of social and economic development supported the country’s integration into the global economy, in a way that was a clear departure from the Ottoman history, and made interaction with the new Turkey attractive to tourists, to investors, and to people of both the developed and developing nations. Even today as we witness Turkey’s struggle to move forward and occasionally stumble on all fronts it is important to understand how the process began. Now that cultural, social and economic issues are becoming increasingly important in international relations, Turkey, with this rich cultural heritage and potential, is poised to play its role in the exciting journey that humanity will embark upon in this millennium. However, given its multi faceted knowledge domain, the size of the existing market in 62 Cultural Tourism and Poverty Alleviation - The Asia-Pacific Perspective, Madrid, Spain, UNWTO, 2005 p. 1. 63 Ibid 24 Turkey, and its growth potential it is surprising that none 64 of the one hundred plus universities in Turkey offer degree programs in cultural tourism to date. In 2005, over eight decades after Atatürk initiated his cultural reforms as a matter of policy, the UNWTO pronounced: “Using culture as a vehicle of sustainable tourism development is now becoming an important item in the priorities of public policy planners.”65 64 M. Teoman Alemdar, M. Teoman Alemdar, Chair, Bilkent University, Ankara, and Erhan Erkut, Rektor, Özyeğin University, Istanbul. Personal communications, August 26, 2008. 65 Cultural Tourism and Poverty Alleviation - The Asia-Pacific Perspective, Madrid, Spain, UNWTO, 2005 p. 19 25