The Commission for Environmental Cooperation and North

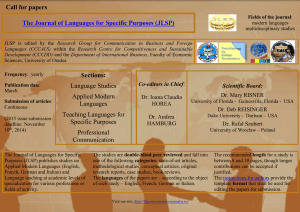

advertisement