Lecture 3

advertisement

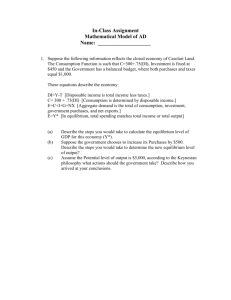

Updated: 21 March, 2007 MICRO ECONOMICS (ECON 601) Lecture 3 Topics to be covered: a. General Competitive Equilibrium b. Edgeworth Box Diagram c. Efficient Allocations d. Production Possibility Frontier e. Rate of Product Transformation f. Determination of Equilibrium Prices g. Real Cost Reduction h. General Equilibrium Modelling i. The Corn Laws Debate j. Existence of General Equilibrium Prices k. Walrasian Solution l. Walras Law m. Definition of Economic Efficiency n. Efficiency in Production o. Efficient Choice of Inputs for a Single Firm p. Efficient Allocation of Resources among Firms r. Efficient Choice of Output by Firms s. Theory of Comparative Advantage ECON 601 Nicholson Chapter 12 General Competitive Equilibrium Partial Equilibrium Analysis Px S P2 P1 D1 D0 O Q1 QX Q2 Initial Price Quantity (P1, Q1) If something causes the demand for X to increase, then a new equilibrium is reached at (P2, Q2). However for the quantity supplied to increase the factors of production that produce X must come from somewhere else. PY S1 S0 P Y2 P Y1 D O Q Y2 Q Y1 QY The resources that produced greater supply of X are equal to the resources released from Y when production fell from QY1 to QY2. I Law of One Price: A homogeneous good trades at the same price no matter who buys it or which firm sells it. 1 II Assumptions about Perfect Competition: - Large number of buyers of each good. Each person takes all prices as given, maximizes utility subject to a budget constraint. Large number of firms producing each good. Firms maximize profits- all prices, both output and input prices, are given to each firm. III General Equilibrium via Edgeworth Box Diagram Assumptions: 1. All individuals have same preferences 2. Two goods X & Y 3. Two factors of production K & L 4. Fixed amounts of K & L. Labor used in X Labor used in Y OY Total Capital Capital used in Y A OX Capital used in X Total Labor A is any production point that uses up all the factors. Efficient Allocations in Production OY Total Capital P4 Y1 P3 P2 X3 X2 A Y 2 Y3 X1 P1 X4 Y4 OX Total Labor 2 A is not an efficient point (X2, Y2) at P2 can produce same X2 but produce more Y3 at P3 can produce same Y2 but at same time produce more X3. The locus of the points P1, P2, P3, P4 are efficient because that is where the isoquants for production of X and production of Y are just tangent with each other. No more of one good can be produced without less of the other one of being produced. This is referred to as the “Contract Curve”. Along this curve the (Rate of Technical Substitution) RTSXKL = RTSYKL. If one plots these points in X, Y, space they give us the production possibility curve. QY The negative value of the slope of the tangent to the production possibilities frontier is the rate of product transformation Quantity of Y Y4 Y3 Y2 Y1 X1 X2 X3 X4 QX Quantity of X Rate of Product Transformation RPT (of X for Y) = – slope of production possibilities frontier dY = (along OXOY) dX The RPT records how X can be technically traded for Y while continuing to keep the available productive inputs efficiently employed. The “normal” production probabilities frontier exhibits an increasing RPT 3 QY RPT is small Y X RPT is large Y X QX To show that, RPT = dY = MC X dX MC Y Suppose total cost function to society = C (X, Y) dC = C dX + C dY = 0 Y X C C dX = – dY Y X For movement along production function, dY RPT= (along OXOY)= C / C = MC X dX X Y MC Y Why should RPT rise if QY and QX i.e. why RPT as QX 1. 2. 3. Diminishing returns to scale – What happens if constant returns to scale Specialized inputs – Specific factor Differing Factor Intensites in Production of X and Y. – Most general reason why the rate of RPT increases as more of X is produced. Production possibility frontier will be concave if goods X & Y use inputs in different proportions. 4 OZ B Capital P4 W4 P3 Z1 W3 Z2 P2 Z3 P1 OW W2 W1 Z4 Labor W is relatively labor intensive Z is relatively capital intensive B is not as efficient as P3 Production possibilities frontier shows the economic concept of opportunity cost. Society can not have more of X unless it gives up some of Y. Measured by RPT of X for Y. Determination of Equilibrium Prices - Introduce indifference curve map of society U1, U2 U1 U2 QY Y0 A C Y* Slope = – B Y1 PX PY Slope = – X0 X1 X* 5 QX PX * PY * * Px › Px PY * <P Y * Px / PY * >P /P x Y With PX and PY, firms gain maximum profits at A by producing at Y0,X0 Consumers will maximize utility at B with (X1,Y1) Excess demand for X = (X1 – X0) Excess supply of Y = (Y0 – Y1) Hence PX, PY At C (Y*, X*), RPT = MRS Suppose tastes change so that X becomes more attractive – PX – PX 0 PY0 1 PY1 QY Y0 u00 Y1 u01 X1 X0 PX from PX PY PY (Y0, X0) to (Y1, X1). In this case 0 0 to PX 1 u11 QX and the quantity of goods produced and sold will move from PY1 Effect of Technical Progress in Production of X (Real Cost Reduction) 6 Y Y2 u1 Y1 u0 X1 X2 X for sure X2 > X1 Y2 may be <> Y1 depending on the relative strength of income and substitution effects. Example: Comparative Statics in General Equilibrium Model Suppose production function of both goods characterized by DRS as x l x0.5 and y l y0.5 PPF is given as x 2 y 2 100 and by taking total differential of this function and find RPT as 2 xdx 2 ydy 0 MC x dy 2 x x RPTxfory MC y dx 2y y For consume side, consumer preferences are given as utility function U ( x, y ) x 0.5 y 0.5 By setting the Lagrangian expression we can obtain Marginal Rate of Substitution x for y as L x 0.5 y 0.5 ( I Px x Py y ) MRS xfory L MU x x 0.5 x 0.5 y 0.5 Px y Px MU y L 0.5 x 0.5 y 0.5 Py x Py y General Equilibrium Requires RPTxfory x y P MRS xfory x 1 y x Py Therefore, x = y and we can calculate values for x and y by using the PPF 2 2 x 2 y 2 100 x x 100 2 x 2 100 x 50 y 50 7 The Budget Constraint: If w= hourly wage rate we have lx+ly=100 hrs and total labor income is 100w Total, average, and marginal costs for production of x can be calculated as C ( w, x) wl x wx 2 C wx x C MC 2 wx Px 2 w 50 x AC Therefore profit obtained from production of x will be 2 x ( Px AC x ) x (2 wx wx ) x wx 50 w Similarly 50w y Hence, Total Income = Total Labor Income + Profits = 100w+2(50w) = 200w Consumer spends 100w for good x and 100w for good y. This equilibrium can be shown graphically as below QY Quantity of Y 100 RPTx for y=MRSx for y=Px/Py 50 E U Px/Py 0 50 100 This Equilibrium condition can be change due to two reasons: 1. Change in supply (due to technological progress) 2. Change in demand (due to change in preferences) 8 Quantity of X Shift in Supply: Suppose there is technical progress in production of x and production function for x becomes x 2l x0.5 To obtain lx as a function of x x2= 4 lx lx= x2/4 therefore our new PPF would be x2 y 2 100 4 Total differential x dx 2 ydy 0 RPTxfory 2 x ( ) dy 2 x dx 2y 4y In Equilibrium: (supply) RPT (demand) P x x 4 y Py MRS y Px x Py x y 4y x x 2 4 y 2 and x2 y 4 2 x2 y 2 100 4 2 2 4 4 So, x x 100 2 x 2 400 Therefore at Equilibrium RPT x 2 50 and y 50 x y P 1 x 4 y x Py 2 Due to technical progress relative prices of good x and y decreased and consumption of good x increased (doubled). 9 For good y, negative substitution effect and positive income effect offset each other and no change in quantity and price of good y. On the other hand, due to technological progress in x production total utility derived increased from U ( x, y ) x 0.5 0.5 y ( 50) 0.5 ( 50) 0.5 50 7.07 to U ( x, y ) (2 50) 0.5 ( 50) 0.5 2 50 100 10 This is also measurement of welfare change due to technological progress. Shift in Demand: Suppose demand for x significantly reduced and utility function becomes U ( x, y ) x 0.1 y 0.9 By setting up Lagrangian expression subject to budget constraint we can find marginal rate of substitution x for y as MRS xfory y Px 9 x Py y Px x Px and (demand) MRS xfory y Py 9 x Py y Equilibrium should satisfy x y 2 9 x 2 and y 3 x y 9x So (supply) RPTxfory If we substitute these into PPF x 2 9 x 2 100 x 10 Therefore in equilibrium y 3 10 RPTxfory MRS xfory Px 10 1 Py 3 10 3 Due to change in preferences relative prices of good x and y decreased. We cannot compare welfare change here, because utility (preferences) changed. General Equilibrium Modelling and Factor Prices Corn Laws Debate in England 1829-45. High tariffs on grain: Question, should they be reduced? Initially if tariffs prevented, all international trade equilibrium the economy would be at point E. Impact of International trade – on production and returns to factors. 10 Y u YA 0 u1 A E B Slope – (P*X/P*Y) if no grain tariffs YB Slope – (P’X/ P’Y) if tariffs on grain XA X XB With international trade and world prices of P*X and P*Y the country will produce at A with YA, XA, but consumers will be able to consume at B, YB, XB. Hence, country will export (YA – YB) of good Y for (XB – XA) of good X. A higher level of utility can be reached. If Y is manufactured good and X is Corn then we would expect to find that land prices will fall and wage rates rise after allowing international trade. Agriculture production is reduced and because agriculture is land intensive, land prices will fall. As manufacturing will expand and because it is labour intensive, wage rates will rise. Analyses using Edgeworth Box Diagram Mfg A Capital C1 M2 W1/R1 C2 W0/R0 B M1 Corn Labor Corn is capital intensive Mfg is Labor intensive. If one opens up to trade them, production moves from A (more Corn; less Mfg) to B (less Corn; more Mfg) both production processes become more capital intensive, hence, PK, PL. W1/R1 > W0R0 11 Existences of General Equilibrium Prices Problem posed and solved by Leon Walras Question: Does a set of non-negative prices exist that will equilibrate all the markets in an economy? Walrasian Solution 1. Let goods be distributed someway in a society Si (i=1,…,n) Total supply of goods Pi (i=1,…,n) Price of goods ‘i’ Demand for good ‘i’ Di (P1,....,Pn) Demand is a function of all prices P = (P1,…,Pn) Di (P) Di (P*) = Si Expressed as excess demand functions, EDi (P) = Di (P) – Si In Equilibrium, EDi (P*) = Di (P*) – Si = 0 Assumptions: 1. – Assumed that demand functions are homogeneous of degree zero 2. – Demand functions are continuous – Comes from theory of individual behavior Walras Law n P ED ( P) = 0 i 1 i i Total value of excess demand is zero at any set of prices. – – – – Given by the fixed budget constraint Equilibrium conditions in n markets are not independent Hence, we have only (n – 1) equations in (n – 1) unknowns. Hence, what we need to determine for equilibrium is (n – 1) relative prices. Proof: Two goods and two individuals I, II For individual I. PADIA + PBDIB = PASIA + PBSIB Budget constraint PA (DIA – SIA) + PB (DIB – SIB) = 0 12 PA (EDIA) + PB (EDIB) = 0 For individual II. Similarly, we have: PA (EDIIA) + PB (EDIIB) = 0 PA (EDIA + EDIIA) + PB (EDIB + EDIIB) = PA (EDA) + PB (EDB) = 0 Walras proof of Existence of Equilibrium set of Prices (Equilibrium Relative Prices) – – – _ Problem is not solved easily because demand equations are not linear. Prices must be non-negative. In economics a negative price has no meaning. The equilibrium is a simultaneous solution of prices and demands across all markets. Example: General Equilibrium with Three Goods The economy of Oz is composed only of three precious metals: 1- silver, 2- gold, and 3platinum. There are 10 (thousand) ounces of each metal available (S1=S2=S3=10). The demand for gold is given by p p D2 2 2 3 11 p1 p1 and for platinum by p p D2 2 2 3 18 p1 p1 Notice that the demands for gold and platinum depend on the relative prices of the two goods and that these demand functions are homogeneous of degree zero in all three prices. Notice also that we have not written out the demand function for silver but, as we will show, it can be derived from Walras’ law. Equilibrium in the gold and platinum markets requires that demand equal supply in both markets simultaneously: (D2=S2 and D3=S3) To simplify calculations suppose x p2 p1 and p3 p1 Then we can simply calculate values of x and y by using simultaneous equations methods (ie. multiplying the second equation by (-2) and find corresponding value for y). y 2 x y 11 10 2 x y 1 0 x 2 y 18 10 x 2 y 8 0 5 y 15 0 13 Hence, we can obtain values for these relative prices as y=3 and x=2. In equilibrium, therefore, gold will have a price twice that of silver, and platinum a price three times that of silver. The price of platinum will be 1.5 times that of gold. Walras’ law and the demand for silver: Because Walras’ law must hold in this economy we know n pi .EDi ( P ) 0 i 1 p1 ED1 p 2 ED2 p3 ED3 0 p1 ED1 p 2 ED2 p3 ED3 Solving this equation for the excess demands (by moving the fixed supplies to the left hand side) and substituting into Walras’ law yields ED1 2 p22 p12 2 p32 p12 p p2 8 3 p1 p1 ED1 2 x 2 2 y 2 x 8 y (ED=D-S) If we substitute values of x and y, we can see that the market for silver is also in equilibrium (ED1=0) at the relative prices computed previously. The Efficiency of Perfect Competition Adam Smith put forth the idea that a competitive market would ensure that resources would find their way to where they were most valued (the invisible hand). He provided the framework that has given rise to modern welfare economics. The fundamental Theorem of Welfare Economics states that there is a close correspondence between the efficient allocation of resources and the competitive pricing of these resources. Definition of Economic Efficiency – Pareto Efficient Allocation An allocation of resources is Pareto efficient if it is not possible (through further reallocations) to make one person better off without making someone else worse off. Efficiency in Production Production Efficiency: An allocation of resources is efficient in production (or technically efficient) if no further reallocation would permit more of one good to be produced without necessarily reducing the output of some other good. 14 Production possibilities frontier. Y B A C A = technically inefficient B & C = technically efficient X Technically efficiency is a precondition for overall Pareto efficiency. However, technically efficiency does not guarantee Pareto efficiency. The firm may be producing the wrong goods efficiently. Production efficiency: There are three aspects: 1) resource allocation within a single firm 2) 3) 1. allocation of production resources among firms coordination of firms’ output decisions. Efficient choice of inputs for a single firm. We showed this previously with the Edgeworth Box diagram. In algebra, assume: a) firm produces two outputs X, Y. b) fixed amounts of inputs K, L . c) production function for X = f (KX, LX). d) assume full employment of both factors, hence, KY = K – KX and LY = L – LX e) production function for Y Y = g (KY, LY) = g ( K – KX, L – LX) Technical efficiency requires that the output of X be maximized for any given level of Y eg. Y L =f (Kx, Lx) + ( Y – g ( K – KX, L – LX)) 1) L = fK + gk = 0 K X 15 2) L = fL + gL = 0 L X 3) ∂L/∂λ= Y – g ( K – KX, L – LX) = 0 From 1 and 2, fK g = K fL gL RTSX (K for L) = RTSY (K for L) Efficient Allocation of Resources Among Firms – Necessary for overall efficiency. Resources should be allocated to those firms that can use them most efficiently. Suppose: a) Two firms produce X b) Production functions are f1 (K1, L1) and f2 (K2, L2) c) Total supplies of capital and labor are given by K and L Allocation problem is to maximize, X = f1 (K1, L1) + f2 (K2, L2) subject to constraints, K1 + K2 = K L1 + L2 = L Maximization problem, X = f1 (K1, L1) + f2 ( K – K1, L – L1) First order conditions, f f f f X = 1 + 2 = 1 - 2 =0 K 1 K 1 K 1 K 1 K 2 f f f f X = 1 + 2 = 1 - 2 =0 L1 L1 L1 L1 L2 f 2 f1 = K 1 K 2 and, f1 f = 2 L1 L2 16 Rule: The marginal physical product of any resource in the production of a particular good must be the same no matter which firm produces the good. Example Gains from Efficiently Allocating Labor To examine the quantitative gains in output from allocating resources efficiently, suppose two rice farms have production functions of the simple form q k 1 / 4l 3 / 4 , but one rice farm is more mechanized than the other. If capital for the first farm is given by k 1=16 and for the second farm by k2 =625, we have q1 (16)1 / 4 l13 / 4 2l13 / 4 q 2 (625)1 / 4 l 23 / 4 5l 23 / 4 If the total labor supply is 100, an equal allocation of labor to these two farms will provide total rice output of Q q1 q2 2(50) 3 / 4 5(50) 3 / 4 131.6 The efficient allocation is found by setting the marginal productivities equal: MPL1 q1 3 1 / 4 q2 15 1 / 4 l1 MPL2 l 2 l1 2 l 2 4 Hence, for efficiency labor should be allocated so that 1 l14 2 15 1 5 4 l1 3 4 l2 2 4 l 2 0.0256l 2 Given the greater capitalization of farm 2, practically all of the available labor should be devoted to it. With 100 units of labor, 97.4 units should be allocated to farm 2 with only 2.6 units to farm 1. In this case total output will be Q q1 q2 2(2.6)3 / 4 5(97.4)3 / 4 159.1 This represents a gain of more than 20 percent over the rice output obtained under the equal allocation. If capital were not fixed in this problem, marginal productivities of both capital and labor should be equal for firm 1 and firm 2. Efficient Choice of Output by Firms Even though resources may be allocated efficiently both within the firm and between firms, it must be the case that firms also must produce efficient combinations of outputs. 17 Output of Cars Output of Cars RPT1A=1.5/1 RPT0=1/1 RPT0A=2/1 RPT1=1.5/1 Output of Trucks Firm A Output of Trucks Firm B Initially RPTA>RPTB = 1/1 Hence firm A should produce more cars and firm B should produce more trucks. In this way RPTA0 will fall and RPTB0 will increase. So that RPTA1 = RPTB1 Theory of Comparative Advantage First proposed by David Ricardo: Countries should specialize in producing goods of which they are relatively more efficient producers. Suppose we now have two countries A & B, Output of Cars Y Output of Cars Y RPT1A=? Y 1A RPTB=1/1 Y0 B Y 0A RPTB=? RPT0A=2/1 Y1B X1A X0A X0B Output of Trucks Country A Country B X1B X Output of Trucks Both countries would gain if they produced more of the good for which they have a comparative advantage. Country A should produce more of Y and country B should produce more of X. 18 Country A would be able to sell some of the Y produced to country A in exchange for purchase of X. Both countries can be made better off. Initially country A can give up one unit of X and produce 2 units of Y. For country B at its initial position it can be produced one more X for one unit of Y. Hence, if A were to produce one unit less of X and hence produce two more units of Y, it could trade with Country B one of those units of Y for one unit of X and it would be still better off by one unit of Y. At the same time, country B would be left no worse off. World welfare would be improved. – If a linear production function existed in both countries, to maximize world welfare each country should completely specialize in the production of one good. Not the case if concave production functions. 19