Genetically Yours: Bioinforming, biopharming, and

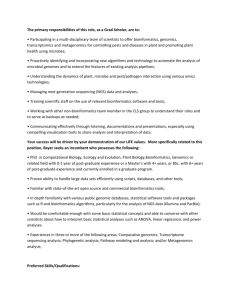

advertisement