Treatment of 54 clinically diagnosed rabies patients with

advertisement

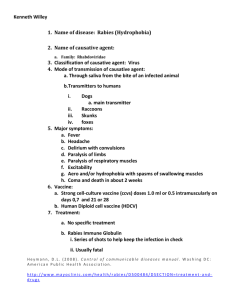

Treatment of 54 clinically diagnosed rabies patients with two survivals G.R. Gode, R. Saksens, R. K Batra, P.K. Kalia & N. K. Bhide Department of Anaesthesiology & *Pharmacology, All India Institute of Medical Sciences, New Delhi Accepted September 19, 1988 Fifty four patients (51 male, 3 female) with characteristic florid manifestations of furious rabies were admitted for treatment with intensive care and drugs. Seventeen patients (group I) on citarabine, nucleic acid lipoprotein complex or interferon inducers, survived for a mean period of 10.4 days. The other 37 patients (group II) on diphenylhydantoin and vitamin C survived for a longer period of 13.3 days; their disease was less severe and the clinical condition was better; 6 of them came very close to recovery before death while two recovered completely. This study spanning over a period of 17 yr suggests that, in the near future, one can hope to have satisfactory treatment for this condition, which has been considered as invariable fatal so far. While prevention of rabies has been successfully established, no treatment schedule has been evolved and the society (including the medical profession ) has always considered this disease to be fatal. In India alone, every year, nearly 15, 000 people, mostly of the younger age group, die of rabies from among the 3, 00, 000 exposed to it1 We report here the response to treatment of 54 patients of furious rabies (51 males and 3 females, aged 6 to 70 yr, mean 21.7 +11.9 SD;47 less that 30yr) at the All India Institute of Medical Sciences, New Delhi, over a period of 17 yr. The most remarkable presenting symptom which had prompted the patients to seek medical help was hydrophobia. The same feature also led to the diagnosis of rabies by the medical attendant. In all the patients, the diagnosis was based on the epidemiological features, a definite history of exposure (one licked by a puppy, 52 bitten by dogs, and one by a mongoose) and classic clinical signs and symptoms of furious rabies including aerophobia and photophobia. In 3 patients in whom autopsy could be carried out the diagnosis was confirmed by the presence of Negri bodies. Facilities for this investigation as also virus inoculation and confirmation were subsequently withdrawn by the concerned departments for fear of contracting the disease. Clinical course was characterized by excess salivation, autonomic dysfunctions, myocarditis, arrhythmias, progressive fatal hypotension, diabetes insipidus, paralytic ileus, gastrointestinal haemorrhages, pulmonary oedema, nosocomial infections, depticaemia and , in one chronic alcoholic patient hypogylcaemia. Intensive care management as described earlier2 was organized in a special isolated room by competent qualified volunteers who were protected by duck embryo vaccine which was replaced in the later years, by human diploid cell vaccine. Hypoxia resulting from spasms and/or paralysis of pharyngeal, cervical and respiratory muscles was prevented by the timely use of sedatives, muscle relaxants and intermittent positive pressure respiration (IPPR) as required. Intensive care was given to all patients of group 1 (17) and group II (37). Patients of group I received the following drugs: (i) cytarabine (cytosar 05-2.0 mg/kg/day iv for 10 days and 5.0-15.0 mg/kg/day iv for the next 8 days); the doses were adjusted according to the peripheral blood cell counts; (ii) nulip (nucleic acid lipoprotein complex, 2 ml dose in every 6 h for up to 4 days); and (iii) Poly I : Poly C (polyriboinosinicpolyribocytidylic acid; 100mg/kg/day iv for up to 4 days). Mean survival in this group was 10.4 days. Diphenylhydantoid (DPH, 3-5 mg/kg/day) and vitamin C as acid and sodium salt (0.5-1.0 mg/kg/day) administered to group II patients (37) for a week, were later tapered depending on the patients’ response. Group II patients showed improvement concerning hydrophobia, agitation restlessness and insomnia. Their clinical picture was milder. Mean survival in group II patients was 13.3 days. Details are given below of the two surviving patients in this group. The two patients were both males aged 18 and 10 yr, and had unprovoked bite in the left lower limbs by stray dogs; one dog died 4 days after the bite whereas the second was killed immediately. Both patients received postexposure, a course of Semple’s vaccine without antiserum and had incubation periods of 4 and 2 months respectively. Fever, pain at the site of bite, paresthesis of the bitten limb, classic hydrophobia, anxiety, conviction and fear of impending death, photophobia an daerophobia were present. Clinical course of the first patient was severe and protracted and the patient required 16 days respiratory support. The second patient had cardiac irregularities, drowsiness alternating with violent behaviour and required oxygen therapy for 3 days but no respiratory support. Both patients are alive and normal, for over 28 and 13 months respectively (at the time of this communication). All our patients had florid and unmistakable presentation of classic furious rabies, the most pathognomonic and specific feature of which is hydrophobia, which is practically unknown in other diseases. Other features supporting the diagnosis are the early complaints of the pain/paresthesia at/around the site of bite with malaise and fever. Post-vaccinal encephalomyelitis has a predominantly paralytic picture and is quite unlike furious rabies with hydrophobia which was present in all our patients. This vaccineinduced disease occurs within 5 wk of the first vaccine injection. Vaccine encephalomyelitis was thus excluded in all our patients including the two who survived. DPH, a bioelectric stabilizer, is effective against seizures and cardiac arrhythmias and exerts an antianoxic effect3. Vitamine C acts as a free radical acavenger4 and has beneficial effect in clinical viral infections and in preventing rabies in infected guineapigs5. It is possible that vitamin C and DPH may have helped the group II patients in our series in more than one way. We wish to emphasize that, with persistence, it may be possible to evolve the direction and treatment and also assure of a certain degree of hope for this disease, which is still considered to be fatal. We are continuing this study in the hope of getting a clear answer. Acknowledgment The contribution of the Infections Disease Hospital, Delhi, for directing the rabies patients to our Department is acknowledged. References 1. Schwabe, C.W. Report of the first WHO regional seminal on veterinary public health (WHO Regional Office for south East Asia, New Delhi) 1971 p 16. 2. Gode, G.R., Raju A.V., Jayalakshmi, T.S., Kaul, H.L. and Bhide, N.K> Intensive care in rabies therapy, clinical observations. Lancet ii (1976) 6. 3. The broad range of use of DPH bioelectrical stabilizer, USA, B. Samuel and J. Drefus, Eds (The Drefus Medical Foundation, USA) p 55. 4. Cathcart, R.F. Vitamin C. The nontoxic, nonrate limited, antioxidant free radical scavenger. Med Hypothesis 18 (1985) 61. 5. Banic, S. Prevention of rabies by vitamin C. Nature 258 (1975) 153. Reprint requests : Dr G.R. Gode, Emeritus Medical Scientist, Department of Anaesthesiology All India Institute of Medical Sciences, Ansari Nagar, New Delhi 110 029