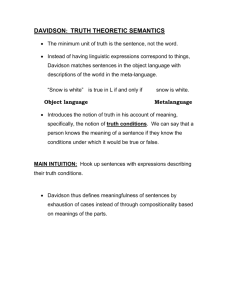

Worksheet on (Carnap and) Davidson

advertisement

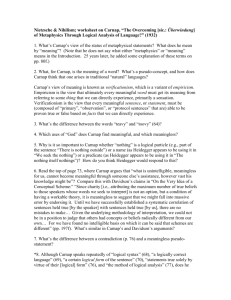

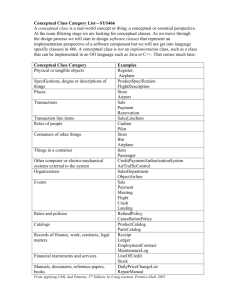

Nietzsche & Nihilism; Worksheet on Rudolf Carnap (1891-1970), “Empiricism, Semantics, and Ontology” (1950); and Donald Davidson (1917-2003), “On the Very Idea of a Conceptual Scheme” (1974) I am assigning this reading because I believe that it expresses essentially the same view of truth and value that Nietzsche holds. Even though Carnap and Nietzsche are frequently regarded as from entirely different philosophical traditions (“analytic” philosophy and “Continental” philosophy), Carnap owes much to Nietzsche. And indeed, Carnap makes his knowledge and admiration of Nietzsche clear in his 1932 “The Elimination of Metaphysics Through Logical Analysis of Language.” (Note: Empiricism is the psychological view that there are no a priori ideas, and that all of our ideas are thus based exclusively on the senses. Semantics is the study of the meaning of words and the conditions under which sentences (i.e., statements, or assertions) are true. Semantics presupposes syntax, the study of the rules governing which combinations of words (and subcomponents of words) count as (well-formed) sentences in a language. (Formal) semantics, which Carnap helped to pioneer beginning in the late 1920’s, operates by taking at first meaningless expressions, i.e., words or sentences, and then assigning an interpretation to them. Such an interpretation determines which objects names in that language designate (or refer to), and the conditions (i.e., possible ways the universe could be) under which sentences in that language would be true. (Sentences are expressions that are either true or false.) For example, take the sentence “München liegt in Bayern.” We can assign this the following interpretation: “München” is a name that in German designates (or refers to) Munich; “Bayern” is a name that in German designates Bavaria; and a sentence of the form “x liegt in y” is true-in-German if and only if x is spatially contained within y. Thus the sentence “München liegt in Bayern” is true-in-German if and only if Munich is spatially contained within Bavaria. Nominalists hold the metaphysical position that only individuals, or particulars, exist; they regard all words – such as “red”, “tall”, or “five” – that appear to designate universals as “empty sounds” (flatus vocis in Latin). They are opposed to realists (in the medieval sense), who hold that abstract entities, or universals – i.e., things, such as Plato’s Forms, that have instances, or examples – exist. Traditionally, ontology is the study of the being of beings, i.e., what it is for something to be as such; ontology is thus something that one does. Carnap dilutes to the set of objects that someone believes exist; thus for Carnap an ontology is something that one has. A linguistic framework, sometimes called a conceptual scheme, is a language, defined by its syntactic rules governing which combinations of expressions count as a word and a sentence, and its semantic interpretation. A subjective idealist holds the metaphysical position that only minds and their ideas exist; thus neither physical objects nor abstract universals exist.) 1. What, in your own words, is the distinction between an internal questions about the existence of things and external questions about the existence of things? Which kind of question can actually be answered, decided, or solved factually – and why? *2. What factors enter into our decision about which language we ought to use (p. 208, p. 221)? How are these related to Nietzsche’s will to power? 1 (A sentence is “analytic, i.e., logically true” [p. 209], if and only if its truth can be decided not by the empirical observation of facts, but simply by the logical analysis of the meanings of the terms involved. Analytic truths are opposed to synthetic ones. For example, the sentence “All bachelors are unmarried” is analytically true (since “bachelor” just means “unmarried adult male”), but “All human beings are less than 10 feet tall” is true but not analytically so (since one has to observe facts in the world to determine whether it is true or false). 3. Try to paraphrase Carnap’s argument that the sentence “There are numbers” is an answer to an internal question, but not to an external one. 4. By p. 208, Carnap has argued that internal questions are decided by appeals to facts. This is because internal questions are answered just by true sentences, and facts are just what make sentences true. External questions, on the other hand, are not decided by appeals to facts, but rather just by the choice of a linguistic framework. In the last sentence of the first full paragraph on p. 208, however, he claims that “the efficiency of [a particular] language” is a fact, and can be appealed to in deciding whether to adopt a linguistic framework. Do you see any way in which he can get around this apparent contradiction? 5. What does Carnap make of the attempt to ask whether there really are numbers, independently of which linguistic framework we adopt (p. 209)? *6. Take the sentence “God exists.” Is this an internal or an external question? Why? (Feel free to skip Carnap’s discussion of “The system of propositions” and the several short sections that follow it [pp. 209-213]; pp. 213-220 are also rather technical, and may be skimmed.) 7. The last paragraph of this essay contains what has been called Carnap’s “principle of tolerance” of linguistic frameworks. Try to paraphrase it. What do you think Nietzsche would say about it? (Here’s some background on Davidson: Davidson was a student of V.W.O. Quine, who was Carnap’s greatest critic. Quine rejects Carnap’s view that every truth is either analytic or synthetic. Quine labeled the belief in the analytic-synthetic distinction a “dogma of Empiricism.” Instead, Quine argues, this distinction is not a difference of kinds of truths, but rather merely of the degree to which we are inclined to maintain a belief in the face of evidence that might appear to contradict it. Quine’s basic metaphor is the “web of belief.” Beliefs located toward the center of the web are those that we are most strongly inclined to maintain, come what may; whereas beliefs located toward the outer boundaries of the web are those that we are most likely to give up in the face of apparently contradictory evidence. This evidence comes from what surrounds the web of belief: our immediate experiences of our sensory inputs, or sense-data, which Quine labeled “surface irritations.” Davidson’s primary target in this essay is Quine’s acceptance of the traditional Empiricistic distinction between (1) “immediate experience” (i.e., sense-data), or (empirical) content, that are “uncontaminated” by interpretation or the use of concepts; and (2) a linguistic framework, or conceptual scheme, that forms the structure of our web of beliefs and that we use to interpret our experiences. For Davidson, this distinction labels this is yet another, “and perhaps the last” (p. 189), dogma of Empiricism. For Davidson, the only evidence that there could be for such a distinction would be the existence of two or more conceptual schemes (i.e., languages or 2 scientific theories) that employ such different concepts that one scheme contains (some) sentences that cannot be translated into the other – i.e., that has truth-conditions not expressible in the other. Conceptual relativism is the view that there are such untranslatabilities. If no such evidence can be found, or if the very notion is absurd or unintelligible, then we have no reason to accept “the very idea of a conceptual scheme.” The linguist Benjamin Lee Whorf claimed that this obtains between the Hopi language and such Western European languages as English. The historian of science Thomas Kuhn labeled such untranslatability “incommensurability,” and claimed that it holds among different scientific theories, or “paradigms” (e.g., Aristotelian physics, classical Newtonian physics, and Einstein’s theory of relativity), separated by a “scientific revolution”, or “paradigm shift.” I’ve assigned this Davidson piece because I want you to think about how good Davidson’s criticisms of Quine’s distinction between immediate experience and conceptual schemes are, and whether these criticisms also apply to Nietzsche’s view of value-systems.) 1. Davidson’s first criticism of the very idea of a conceptual scheme, found in the first full paragraph of p. 184, is based on what he takes to be a paradoxical fact about the greatest proponents of the idea. What is this? 2. Davidson’s second criticism of the very idea of a conceptual scheme, in the four paragraphs beginning with the first full paragraph on p. 188, is based on the argument that, even if someone else were employing a different conceptual scheme, there would be no way for us ever to discover this. What is this argument? What conclusion are we entitled to draw from it? Next, Davidson divides up the metaphors typically used to explicate the notion of a conceptual scheme into two main groups: (1) organizing, systematizing, or dividing up the empirical content (in which case we can be conscious of empirical contents only if we have already applied concepts to them; this is Kant’s view, according to which the basic form of empirical experience is the judgment, which employs concepts to link objects of sense-experience); and (2) fitting, predicting, accounting for, or facing up to the empirical content (in which case we can be directly conscious of empirical contents, i.e., without applying concepts to them; this is the view of all Empiricists, including Quine). Davidson then divides up the metaphors typically used to explicate the notion of empirical content into two main groups: (a) a single thing, i.e., reality, the universe, the world, or nature (this is Kant’s view when he speaks of the thing in itself); and (b) a multiplicity of things, either individual sensations or physical facts (this is the view of all Empiricists, but also of Kant when he speaks of the manifold of objects of sensory intuition). 3. What’s Davidson’s argument (in the first two full paragraphs on p. 192) against the intelligibility of 1a: conceptual schemes organize reality? 4. What’s Davidson’s argument (in the last three paragraphs that begin on p. 192) against the intelligibility of 1b: conceptual schemes organize the stream of experiences? 5. What’s Davidson’s argument (in the four paragraphs that begin on p. 193) against the intelligibility of 2b: conceptual schemes fit the stream of experiences, or facts? 6. Note that Davidson fails to argue against the intelligibility of 2a: conceptual schemes fit (or fail to fit) reality. This would appear to be Kant’s considered opinion. Ludwig Wittgenstein [1889-1951] articulates 2a in his 1921 Tractatus Logico-Philosophicus, which had a profound impact on Carnap: 3 Newtonian mechanics, for example, imposes a unified form [i.e., a conceptual scheme] on the description of the world. Let us imagine a white surface with irregular black spots on it. We then say that whatever kind of picture these make, I can always approximate as closely as I wish to the description of it by covering the surface with a sufficiently fine square mesh, and then saying of every square whether it is black or white. In this way I shall have imposed a unified form on the description of the surface. The form is optional, since I could have achieved the same result by using a net with a triangular or hexagonal mesh. Possibly the use of a triangular mesh would have made the description simpler: that is to say, it might be that we could describe the surface more accurately with a coarse triangular mesh than with a fine square mesh (or conversely), and so on. The different nets correspond to different systems for describing the world [i.e., to different conceptual schemes]… The possibility of describing a picture like the one mentioned above with a net of a given form tells us nothing about the picture… Similarly the possibility of describing the world by means of Newtonian mechanics tells us nothing about the world [i.e., the one and only empirical content of our beliefs]: but what does tell us something about it is the precise way in which it is possible to describe it by these means” [sections 6.341-6.342]. Do you agree with Kant, Wittgenstein, and Carnap that option 2a is in fact plausible? Explain. 7. What does Davidson conclude about failures to translate sentences in one language into those of another? (The principle of charity is the assumption that the speaker and you agree in general on your beliefs, i.e., on which sentences you hold to be true. This is what makes it possible to figure out what someone meant to say, even if you speak different, or slightly different, languages. Davidson regards our applying the principle of charity as a necessary condition of the possibility of understanding, or interpreting, someone’s statements.) (A ketch and a yawl [p. 197] are both two-masted sailboats, where the only difference is the location of the small jigger mast: in a ketch it’s forward of the rudder, whereas in a yawl it’s abaft the rudder. Ahoy, maties!) 4