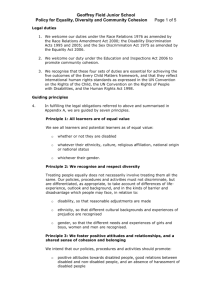

Research report 42 - Good relations a conceptual analysis

advertisement