POM1 Module 2 - Integrative Medicine

advertisement

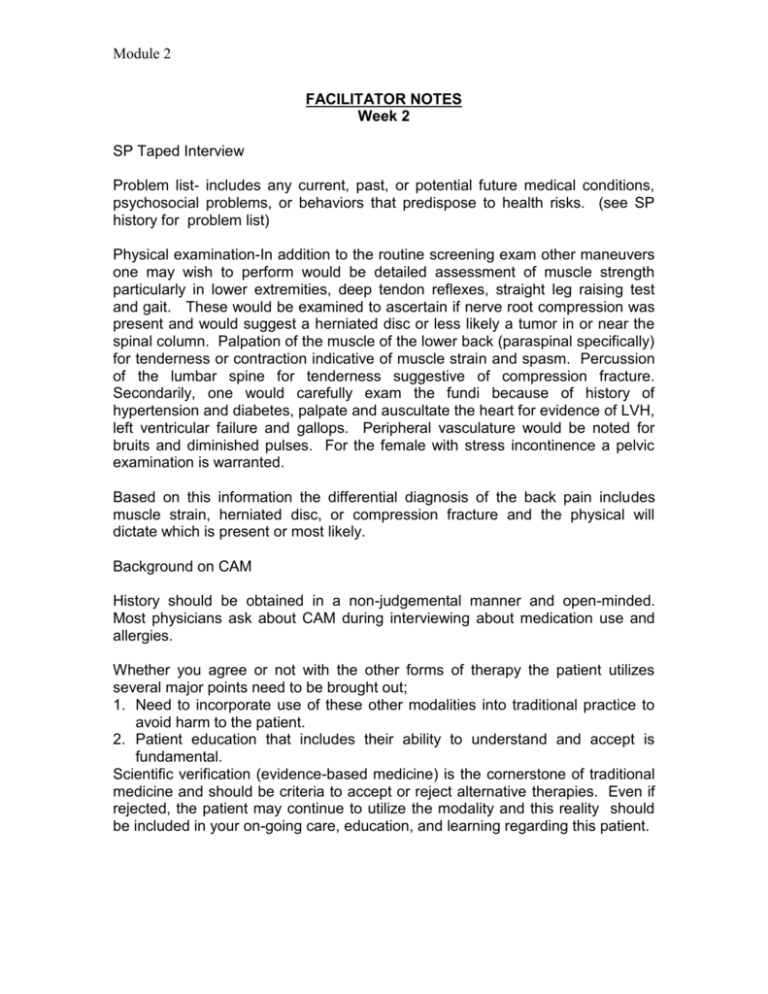

Module 2 FACILITATOR NOTES Week 2 SP Taped Interview Problem list- includes any current, past, or potential future medical conditions, psychosocial problems, or behaviors that predispose to health risks. (see SP history for problem list) Physical examination-In addition to the routine screening exam other maneuvers one may wish to perform would be detailed assessment of muscle strength particularly in lower extremities, deep tendon reflexes, straight leg raising test and gait. These would be examined to ascertain if nerve root compression was present and would suggest a herniated disc or less likely a tumor in or near the spinal column. Palpation of the muscle of the lower back (paraspinal specifically) for tenderness or contraction indicative of muscle strain and spasm. Percussion of the lumbar spine for tenderness suggestive of compression fracture. Secondarily, one would carefully exam the fundi because of history of hypertension and diabetes, palpate and auscultate the heart for evidence of LVH, left ventricular failure and gallops. Peripheral vasculature would be noted for bruits and diminished pulses. For the female with stress incontinence a pelvic examination is warranted. Based on this information the differential diagnosis of the back pain includes muscle strain, herniated disc, or compression fracture and the physical will dictate which is present or most likely. Background on CAM History should be obtained in a non-judgemental manner and open-minded. Most physicians ask about CAM during interviewing about medication use and allergies. Whether you agree or not with the other forms of therapy the patient utilizes several major points need to be brought out; 1. Need to incorporate use of these other modalities into traditional practice to avoid harm to the patient. 2. Patient education that includes their ability to understand and accept is fundamental. Scientific verification (evidence-based medicine) is the cornerstone of traditional medicine and should be criteria to accept or reject alternative therapies. Even if rejected, the patient may continue to utilize the modality and this reality should be included in your on-going care, education, and learning regarding this patient. Module 2 Taped Interview Module 2 Week 2 Demographics 56 year-old married male/female who lives with his/her wife/husband and two children in an affluent section of Galveston. Chief Complaint “I’ve had pain in my low back for the last 10 days” HPI Patient describes pain in the lower mid-section of his/her back. The pain is a dull ache in nature. It is a constant pain. A heating pad helps reduce, but does not totally relieve, the pain. He/She went to a chiropractor for spinal manipulation, but states it does not seem to have helped very much like it did 4 years ago with a similar episode. Answers to specific questions: Pain first occurred acutely when he/she was lifting a heavy box in the garage Pain is a 5/10 intensity, bending or lifting exacerbate the pain Bedrest improves the pain Pain does not radiate down his/her legs Pain is partially relieved by 1000mg Tylenol There are not paresthesias (abnormal sensations) in his/her legs No abnormal/spontaneous movements of his/her legs No previous trauma to the lumbar area PMH He/She has had diabetes for the last 20 years controlled on “pills” called glipizide. He/She does not check his/her blood sugars regularly. Has hypertension for the past 20 years controlled with a diuretic, hydrochlorothiazide. He/She sees his/her doctor once or twice a year. He/She doesn’t remember when he/she had his/her last immunizations. He/She has no known drug allergies. FH Father is 77 and has diabetes and hypertension. Mother is 74 and had breast cancer treated with surgery 10 years ago. Once brother 44 years with diabetes and one sister 42 alive and well. One son age 11 alive and well and a daughter age 7 alive and well. Module 2 SH Works as a manager of the local K-Mart. Lives in a house with his/her wife/husband of 20 years and two children. Smoked 1 ppd cigarettes for 10 years, but quit 6 years ago. Drinks a beer with dinner. No illicit drug use. Bowls with his/her friends in a league once a week and spends of his/her off time with his/her family. He/She works 60 hours a week at the K-Mart. His/Her sexual relations with his/her wife/husband have been progressively less frequent, “I just don’t have the same desire I used to, maybe I am getting old”. ROS Patient has been overweight all of his/her life. He/She has gained 25 pounds over the last 18 months and now weighs 268 pounds (223 for female). He/She has been trying to lose weight but eats a lot of junk food at work. He/She has “stress headaches” almost every day that he/she treats with Tylenol. He/She attributes this to his/her job. No other problems. Pertinent Review of Systems Decreased energy Allergic rhinitis Lower dentures Dyspepsia (heartburn) after spicy or heavy meals and sometimes when lying supine Pain in both knees if stands too long or walks too far History of UTIs x 4 if female and with stress incontinence Dyspnea on exertion Discussion 1. Problem List a. Low back pain b. Headaches c. Obesity d. Diabetes Mellitus e. Essential hypertension f. Knee pain g. UTI (female) h. Stress incontinence (female) i. Allergic rhinitis j. Dyspepsia k. History of tobacco use l. Alcohol use m. FH of diabetes, hypertension, breast cancer 2. Differential Diagnosis (Low back pain only) a. Muscle strain-exacerbated by body habitus b. Herniated inter-vertebral disc c. Compression fracture of vertebral bodyPhilip LaBarbera, MD Module 2 Evidence-Based Curriculum in Alternative Therapies Victor S. Sierpina, MD CATEGORIES OF ALTERNATIVE MEDICINE The National Institutes of Health and its National Center for Complementary and Alternative Medicine define 5 areas of alternative medicine for the purposes of research and clinical care. These are briefly described and listed as follows: Alternative Medicine Systems are complete systems of theory and practice that have developed outside of the western medical approach, e.g. traditional oriental medicine (including practices such as acupuncture) ayurvedic medicine, homeopathy, naturopathy. Mind-Body Therapies employ a variety of non-mainstream techniques intended to facilitate the mind’s capacity to affect bodily function and symptoms, e.g. meditation, dance therapy, prayer, mental healing, relaxation therapies, stress management. Biological-based Therapies include natural and biologically based practices, interventions, and products, e.g., herbal, special dietary, orthomolecular, and individual biological therapies, nutritional supplements. Manipulative and Body Based Therapies include methods based on manipulation and or movement of the body, e.g., chiropractic, osteopathy, massage therapy, or other body work. Energy Therapies focus on energy fields originating from within the body (biofields) or those from other sources (electromagnetic fields), e.g., Qi Gong, Reiki, Therapeutic Touch, and use of pulsed fields or magnet fields. RESEARCH ISSUESAND CLINICAL USE OF ALTERNATIVE THERAPIES While each of these areas has been used clinically, some such as acupuncture or ayurveda for thousands of years, research on the benefits, safety, cost, and efficacy continues to evolve. Many studies on these alternative therapies have historically been poorly designed, lack adequate sample size, controls, clearly defined inclusion and exclusion criteria, experimenter blinding, and so on that we consider essential to reliable study design. This is largely why these therapies continue to be considered “alternative.” With increased public awareness and use of these therapies along with federal and other Module 2 funding for research, it is becoming increasingly clear which of these therapies are useful, cost-efficient or cost-additive, and how and if they should be integrated within our health care systems. Despite conclusive studies, however, between 40-50% of adults in the US use alternative therapies. They make more visits to alternative practitioners than to primary care physicians. And they spend $28 billion annually, mostly out-of-pocket, for these services, a figure that approximates their expense for all other medical services (Eisenberg 1993, 1998). THE ROLE OF ALTERNATIVE THERAPIES IN LOW BACK PAIN: A Brief Review of Opposing Evidence The most commonly used alternative therapies for back pain are: 1) spinal manipulation, e.g., chiropractic or osteopathy, 2) acupuncture, 3) massage. These are in the categories of manipulative or body-based therapies (chiropractic, osteopathy, and massage) and alternative systems of care (acupuncture). Low back problems are one of the most common causes of both acute and chronic pain. They form a heterogeneous group of disorders often lumped together as “low back pain,” “sciatica,” or “lumbago.” Though serious conditions such as ruptured intervertebral discs, fractures, tumors, and infections can cause low back pain, the majority of cases defy precise anatomical definition. Treatments, therefore, are often used that either seem to work or offer hope of improvement while the back pain resolves, often on its own. This makes the study of the benefits of any therapy complex. A recent review article (NHS Centre, 2000) utilized the Cochrane Collaboration systematic reviews to assess the “best evidence” for the treatment of both acute and chronic back pain. (See Tables 1 & 2). While they described a wide variety of approaches, evidence for effectiveness was strongest in acute back pain for: 1) advice to stay active, 2) non-steroidal anti-inflammatory drugs (NSAID’s), 3) muscle relaxants, 4) analgesics. For chronic back pain, best evidence favored: 1) back schools, 2) behavioural treatments, 3) exercise therapy, 4) multidisciplinary programmes, 5) NSAID’s. What are we to make of the failure the most commonly used alternative therapies for back pain, spinal manipulation, acupuncture, and massage to be proven as effective? Indeed, they are described in this review as having either “unclear effectiveness” or “evidence for ineffectiveness.” One explanation is that methodology of studies on these therapies was often poor, failing to support the benefits many individual patients claim for relief. Indeed, there are some studies showing the adverse events of such therapies such as cerebrovascular accidents with spinal manipulation and pneumothorax with acupuncture. This clearly indicates as need for more and better studies before these therapies can be considered mainstream medicine. Yet patients continue to seek these therapies despite final scientific documentation of clinical effectiveness for personal reasons, and perhaps because of Module 2 individualized benefits that cannot be adequately supported by the randomized controlled trial. Other studies, do show suggestion of effectiveness for such alternative therapies. For example, a prospective, randomized study comparing acupuncture with physiotherapy for low back pain in pregnant women showed significant decrease in pain in the acupuncture group over the physiotherapy group as rated by the Visual Analog Scale (VAS). It also showed a significant decrease in the Disability Rating Index (DRI) in the acupuncture group (Wedenberg, 2000). Though a small study, this suggests some benefit for acupuncture in this population. Chiropractic has certainly found a major place in our health care system both here and abroad is reimbursed by major insurance carriers, including Medicare. To reach this level of acceptance by third-party payors, clearly some scientific support was required and many studies do show a place for this modality in back pain(Waddel, 1996, Manga, 1993). An outcomes study on chiropractic treatment for low back pain vs. treatment by family physicians showed 31% of patients had reduction of pain after 1 month in the manipulation group compared to 6% in the physician group (Nyiendo, 2000). This indicated that perhaps those choosing chiropractic care may be more likely to recover from back pain, though by no means proved it. Massage has been widely studied and is the most frequently used treatment for back pain on the European continent. Results using massage therapy as a control show its effectiveness in systematic review but fall short of conclusive evidence (Ernst 1999). A study comparing comprehensive massage (soft tissue work, remedial exercise, and posture education) with soft tissue massage only, remedial exercise with posture education, and sham-laser therapy showed significant improvement in decreased pain in the comprehensive massage therapy group compared to any of the other groups (Preyde, 2000). CONCLUSION: Clearly, these alternative therapies for back pain have not only wide usage but are supported by some clinical studies. While the overall evidence for their effectiveness remains inconclusive, clinical trials suggest benefit in some populations. A wide range of other alternative therapies are also used for back pain and other musculoskeletal disorders, again with a varying level of evidence for their effectiveness (see Table 3). POTENTIAL QUESTIONS FOR SMALL GROUPS: 1) If a patient presented with chronic back pain and insurance plan that covered acupuncture, chiropractic, or massage, which, if any would you recommend? What if the patient demanded a referral? What would you say? 2) How can the results of a randomized controlled clinical trial differ from a systematic review or meta-analysis? Module 2 3) How do you make rational clinical decisions in the face of conflicting or inconclusive data from the medical literature, as illustrated in this discussion? 4) What has been your real-life experience with any of these alternative therapies? Have friends or members of your family used them, been benefited or relieved? Have any sustained an injury or other adverse outcome with these alternative therapies? Answer these same questions for conventional medical or surgical interventions? REFERENCES: Eisenberg D, et al. 1993. Unconventional medicine in the United States. Prevalence, costs, and patterns of use. N Engl J Med 328:246–242. ——, et al. 1998. Trends in alternative medicine use in the United States, 1990–1997: results of a follow-up national survey. JAMA 280:1569–1575. Ernst E. Massage. 1999. Massage therapy for low back pain: a systematic review. Pain Symptom Manage 17:65-69. Manga P, et al.1993. The effectiveness and cost effectiveness of chiropractic management of low back pain. Toronto: Ontario Ministry of Health. NHS Centre for Reviews and Dissemination. Acute and chronic low back pain. 2000. Effective Health Care 6(5): 1-8. Nyiendo J et al. 2000 Patient characteristics, practice activities, and one-month outcomes for chronic, recurrent low back pain treated by chiropractors and family medicine physicians: a practice-based feasibility study. J Manipulative Physiol Ther 4:239-245. Preyde M. 2000 Effectiveness of massage therapy for suacute low-back pain: a randomized controlled trial. Can Med Assoc J 162: 1815-20. Waddel G, et al. 1996. Low Back Pain Evidence Review. London: Royal College of General Practitioners. Wedenberg K, et al. 2000. A prospective randomized study comparing acupuncture with physiotherapy for low-back and pelvic pain in pregnancy. Acta Obstet Gynecol Scand 79: 331-35. Module 2 Box 1 – Summary of the effectiveness of conservative treatments for acute low back pain (adapted from Van Tulder et al. 2000)* Evidence for effectiveness Advice to stay active NSAIDs Muscle relaxants Analgesics Unclear effectiveness (no, limited or contradictory evidence for effectiveness) Acupuncture Back schools Behavioural treatments Colchicine Electro myographic biofeedback Epidural steroid injections Facet joint injections Ligamental injections Lumbar supports Multidisciplinary programmes Physical treatments Spinal manipulations Traction Transcutaneous electrical nerve stimulation (TENS) Trigger point injections Evidence for ineffectiveness Bedrest Exercise therapy *Tulder M, van, Koes B, Assendelft W, et al. Acute low back pain: activity, NSAID’s and muscle relaxants effective; bedrest and targeted exercise not effective; results of systematic reviews. Ned Tijdschr Geneeskd 2000;144:1484-9. Cited from: Acute and Chronic Low Back Pain in Effective Health Care. 2000;6(5):1-8. Module 2 Box 2 – Summary of the effectiveness of conservative treatments for chronic low back pain (adapted from Van Tulder et al. 2000)* Evidence for effectiveness Back schools Behavioural treatments Exercise therapy Multidisciplinary programmes NSAIDs Unclear effectiveness (no, limited or contradictory evidence for effectiveness) Advice to stay active Analgesics Antidepressants Bedrest Colchicine Epidural steroid injections Ligamental injections Lumbar supports Muscle relaxants Physical treatments Spinal manipulations Transcutaneous electrical nerve stimulation (TENS) Trigger point injections Evidence for ineffectiveness Acupuncture Electro myographic biofeedback Facet joint injections Traction *Tulder M, van, Koes B, Assendelft W, et al. Acute low back pain: activity, NSAID’s and muscle relaxants effective; bedrest and targeted exercise not effective; results of systematic reviews. Ned Tijdschr Geneeskd 2000;144:1489-94. Cited from: Acute and Chronic Low Back Pain in Effective Health Care. 2000;6(5):1-8.