Introduction

One of the keys to effective management lies in harnessing the motivation of

employees in order to achieve the organisation’s goals and objectives. Motivation

is therefore a key topic in the study of organisational behaviour. This chapter

discusses several motivation theories and the concept of empowerment in terms of

how they may contribute towards increasing both productivity and the quality of

working life. The theories in this chapter are an important foundation for the ideas

to be developed throughout the rest of this book. Before looking at the separate

theories, two key points should be made. First, motivation to work refers to

forces within an individual that account for the level, direction and persistence of

effort expended at work. Within this definition of work motivation:

• level — refers to the amount of effort a person puts forth (for example, a lot or

a little)

• direction — refers to what the person chooses when presented with a number

of possible alternatives (for example, to exert effort on achieving product quality

or product quantity)

• persistence — refers to how long a person sticks with a given action (for

example, to try for product quantity or quality, and to give up when it is difficult

to attain).

Motivation to work refers to the forces within an individual that account for the

level, direction and persistence of effort expended at work.

Second, it is important to emphasise that motivation to work (or willingness to

perform) is one of three components of the individual performance equation,

which was presented in chapter 2 (the other two are the capacity to perform and

organisational support). High performance in the workplace depends on the

combination of these three individual performance equation factors (as will be

emphasised later in the chapter when motivation theories are integrated).

Motivating and empowering the workforce

Each employee is different, each organisation’s workforce may have different

characteristics, and at different times or in different locations there may be

different circumstances that affect motivation and empowerment strategies in

different ways. In order to meet the challenge of motivating employees, managers

must be concerned with the context in which this is being done. Managers also

need to understand the challenges of the work effort–motivation cycle.

1 LEARNING OBJECTIVE

Motivating and empowering today’s workforce

Contemporary issues affecting motivation and

empowerment

When considering motivation, contemporary organisations are not just dealing

with existing employees — they must also consider how they might attract

future employees. They are concerned about attracting and retaining employees,

especially in a competitive labour market. The business media carries much

discussion relating to competition for talented workers as well as on attracting

and retaining staff, engaging employees, providing employee benefits, rewards

and remuneration programs and helping employees to balance work and life

demands. These and many other contextual factors for motivation illustrate how

difficult and complex it can be for employers to motivate employees and to

enhance their performance. Organisations that fail to recognise these contextual

factors and their implications for workplace motivation risk losing their best

people to other organisations with more exciting, satisfying or rewarding

opportunities. Some particular contemporary issues that underpin these concerns

are labour skills shortages, an ageing population and workforce mobility. These

are briefly summarised below. Motivation is applied in workplaces through the

use of various strategies such as the provision of workplace rewards, job

designing and flexible work places.

Labour skills shortages

Leading up to, and during, 2008 the business media carried a lot of advice

about labour and skills shortages and competition for talent. Shortages among

employees such as accountants, chefs, metal tradespersons and construction

workers were very evident. Regionally uneven, the shortages in the Northern

Territory, South Australia and Queensland were increasing while a survey of

more than 500 businesses in Australia found that 73 per cent of Victorian

companies nominated the inability to employ skilled staff as a barrier to their

success.1 Skills shortages in New Zealand were the main constraint on

expansion for just under one-third of organisations in the services sector and

44 per cent of building firms were experiencing problems finding skilled staff.

There were also high vacancy levels for agriculture and fishery workers, and

for machine operators and assemblers, with shortages perceived to be worse

on the South Island.2

With the global financial downturn that began in late 2008, a sudden change in

the labour market was seen. The large-scale retrenchments of the 1990s

returned, with unemployment rising, overshadowing the focus on skills

shortages and talent wars. However, skills shortages can and do coexist with

high unemployment3 and despite a sudden shift in the labour demand, some

skills shortages will remain and in the future new shortages may develop. Both

Australia and New Zealand had modified their immigration policies to attract

more skilled immigrants but in response to more recent developments

Australia temporarily reduced its intake for 2009.4 High levels of competition

for ‘talented’ workers may continue in some areas despite economic downturn

and many employers will need to maintain their efforts for attracting and

retaining talent. One of many explanations about why skills shortages emerged

was that professions had a poor image in terms of compensation, career path

and development opportunities and young people chose to seek out other

careers.5 Whenever labour shortages occur (such as when there are particular

skills shortages or as the population ages) there will be a growing need for

organisations to carefully consider employee needs and expectations as well as

how they can attract and retain trained and skilled workers and older

employees. A method they might use is looking at groups that have previously

been underutilised — such as people with disabilities, indigenous people,

older people, women who wish to work part-time and international workers.6

Profiles of employees over time may necessitate adjustments so employee

benefits and rewards suit the different personalities in a workplace.

The ageing population

In conjunction with skills shortages, the ageing population is contributing to a

potential ‘experience deficit’ as older workers retire.7 In Australia, the median

age will rise from 35 years to between 43–46 years by 20518 and the rate of

effective growth in labour supply will be slower than population growth.9

There will still be services that need to be provided to the community but

organisations may have trouble finding enough employees to work to provide

those services. JobNetwork findings indicate that while there were six workers

for every retired person in Australia recently, by 2025 there will only be three

workers for every retired person.10 Responses by organisations to these

looming problems vary. Studies reveal 80 per cent of Australian businesses are

struggling to compete for talent and 59 per cent of businesses are aware the

ageing population is affecting their work environment. However, only about

46 per cent of businesses are doing any workforce planning and about 17 per

cent have strategies for recruiting and retaining older workers.11 Some

organisations still focus on hiring only younger employees12 and consider

older workers who are looking for employment to be too old.13 Considering

the particular needs of older employees is important for staff retention levels

and for attracting new employees from older age groups. For example, health

and well-being programs may be more attractive to older employers. Such

programs have been shown to provide a 3: 1 return on investment by

Pricewaterhouse-Coopers14 and, along with employment itself, to have value

in preventing illness in older age.15 It is also evident that many older people

emphasise the importance of job satisfaction and self-worth in their work, and

some report that they would not work unless they could have work that was

satisfying and worthwhile.16 More men than women are interested in working

in their retirement.17 As the following example from Australia Post shows,

there is a lot of focus on considering the needs of different age cohorts in

organisations, especially in the context of competitive labour markets.

Workforce mobility

Another feature of many workplaces is the mobility of the workforce. This

relates to the willingness of workers to move from job to job and from

organisation to organisation. Many young people opt to travel and work

overseas for extended periods. As a result of the Australian resources boom,

many people are being tempted to accept jobs that require them to work in hot

and isolated locations — sometimes thousands of kilometres from their homes

— for high financial rewards. For some it is a case of flying in and flying out

for work and missing time with family or being subjected to excessive

tiredness from travelling long distances.19 Mobility also relates to the trend for

organisations to seek whole workforces from other locations (such as from

different states, provinces or countries). Many organisations are already

familiar with multicultural workforces, either domestically or in various global

locations. Motivation of different cohorts within the workforce may require

local or cross-cultural knowledge and an understanding of the psychological

bond an employee has with the organisation. The following International

spotlight discusses the importance and prevalence of sourcing workforces

from other locations.

The work motivation challenge

Managers in organisations affected by such changes and pressures must build or

rebuild loyalty and commitment, and create a positive organisational climate in

which employees are motivated to achieve at high levels of work performance.

This challenge is examined in more detail in figure 3.1. The figure shows how

an individual’s willingness to perform is directly related to the needs,

expectations and values of the individual, and their link to the incentives or

aspirations presented by the organisational reward system. Rewards fulfil

individual goals such as financial remuneration and career advancement.

FIGURE 3.1 • Understanding the work effort–

motivation cycle

The degree of effort expended to achieve these outcomes will depend on:

•

the individual’s willingness to perform, and his or her commitment to

these outcomes in terms of the value attached to a particular outcome

•

the individual’s competency or capacity to perform the tasks

•

the individual’s personal assessment of the probability of attaining a

specific outcome

•

the opportunity to perform (which is central to empowerment,

discussed later in the chapter).

A number of organisational constraints or barriers, if not minimised, may restrict

high levels of individual performance.

Figure 3.1 shows that if the outcome or goal is attained, then the individual

experiences a reduction in pressure or tension, and goal attainment positively

reinforces the expended effort to achieve the outcome. As a result of this

positive experience, the individual may repeat the cycle. On the other hand, if

the outcome is frustrated after a reasonable passage of time then the individual

experiences goal frustration and arrives at a decision point. The individual is

presented with three alternatives:

1.

exit from the organisation

2.

renew attempts at goal achievement, or modify or abandon the goals

3.

adopt a negative response to the frustration experience, and perform at

below–optimum levels.

The challenge for managers is to create organisations in which the opportunities to

perform through competency building and empowerment are maximised and the

impediments to performance are kept to a minimum to avoid the negative

consequences of goal frustration. The next OB in action highlights some of the sorts

of frustration one man experienced in his job in IT. Figure 3.1 shows the complexity

of the work motivational process and emphasises the importance of individual needs,

expectations and values as key elements of this process.

Content and process motivation theories

Two main approaches to the study of motivation are known as the content and

process theories. More recent approaches, based on personal values and selfconcept, are also presented later in the chapter.

2 LEARNING OBJECTIVE

The difference between content and process theories

Content theories are primarily concerned with what it is within individuals or

their environment that energises and sustains behaviour. In other words, what

specific needs or motives energise people? We use the terms ‘needs’ and

‘motives’ interchangeably to mean the physiological or psychological deficiencies

that one feels a compulsion to reduce or eliminate. If you feel very hungry (a

physiological need), you will feel a compulsion to eliminate or satisfy that need by

eating. If you have a need for recognition (a psychological need), you may try to

satisfy that need by working hard to please your boss. Content theories are useful

because they help managers understand what people will and will not value as

work rewards or need satisfiers.

Content theories offer ways to profile or analyse individuals to identify the

needs that motivate their behaviours.

Process theories seek to understand the thought processes that take place in the

minds of people and that act to motivate their behaviour.

The process theories strive to provide an understanding of the cognitive

processes that act to influence behaviour. Thus, a content theory may suggest that

security is an important need. A process theory may go further by suggesting how

and why a need for security could be linked to specific rewards and to the specific

actions that the worker may need to perform to achieve these rewards. Process

theories add a cognitive dimension by focusing on individuals’ beliefs about how

certain behaviours will lead to rewards such as money or promotion; that is, the

assumed connection between work activities and the satisfaction of needs.27

3 LEARNING OBJECTIVE

Content theories of motivation

Content theories

Maslow, Alderfer, McClelland and Herzberg proposed four of the better-known

content theories. Each of these content theories has made a major contribution to

our understanding of work motivation. Some have provided a basis for more

complex theorising in later years.

Maslow’s hierarchy of needs theory

Abraham Maslow’s hierarchy of needs theory (figure 3.2) identifies higherorder needs (self-actualisation and esteem) and lower-order needs (social,

safety and physiological requirements). Maslow’s formulation suggests a

prepotency of these needs; that is, some needs are assumed to be more important

(potent) than others, and must be satisfied before the other needs can serve as

motivators. Thus, the physiological needs must be satisfied before the safety

needs are activated, and the safety needs must be satisfied before the social

needs are activated, and so on.

Higher-order needs are esteem and self-actualisation needs in Maslow’s

hierarchy.

Lower-order needs are physiological, safety and social needs in Maslow’s

hierarchy.

FIGURE 3.2 • Maslow’s hierarchy of needs

The physiological needs are considered the most basic; they consist of needs for

such things as food, water and the like. Individuals try to satisfy these needs

before turning to needs at the safety level, which involve security, protection,

stability and so on. When these needs are active, people will look at their jobs in

terms of how well they satisfy these needs.

The social needs of a sense of belonging and a need for affiliation are activated

once the physiological and safety needs are satisfied. The higher-order needs

depicted in figure 3.2 consist of the esteem and self-actualisation needs — that

is, being all that one can be. Here, challenging work and recognition for good

performance assume centre stage.

Maslow: the research

Some research suggests that there is a tendency for higher-order needs to

increase in importance over lower-order needs as individuals move up the

managerial hierarchy.28 Other studies report that needs vary according to a

person’s career stage,29 the size of the organisation30 and even geographic

location.31 However, there is no consistent evidence that the satisfaction of a

need at one level will decrease its importance and increase the importance of

the next higher need.32 It is interesting to note that, despite being widely

adopted and referred to, Maslow retained concerns and criticisms about his

own theory. For example, in his later writing he appears to have questioned

the position of self-actualisation at the peak of the hierarchy. He moved

beyond this precept to a belief in self-transcendence as the highest level need

(where the individual transcends his or her identity and ego to higher level

aesthetic, mystical and emotional experiences).33 As the Counterpoint shows,

there may be many limitations to our knowledge of needs in terms of how they

apply to different people.

To what extent does Maslow’s theory apply only to Western culture? In many

developing nations the satisfaction of lower-order needs, such as basic

subsistence and survival needs, consumes the entire lifetimes of many millions

of individuals, with little opportunity to progress to higher-level need

satisfaction. But in societies where regular employment is available, basic

cultural values appear to play an important role in motivating workplace

behaviour. In those countries high in Hofstede’s uncertainty avoidance, such

as Japan or Greece, security tends to motivate most employees more strongly

than does self-actualisation. Workers in collectivist-oriented countries such as

Pakistan tend to emphasise social needs

Alderfer’s ERG theory

Clayton Alderfer has developed a modification of Maslow’s hierarchy with the

ERG theory (figure 3.3). ERG theory is more flexible than Maslow’s theory in

three basic respects.41 Firstly, the theory collapses Maslow’s five need

categories into three: existence needs relate to a person’s desire for

physiological and material wellbeing; relatedness needs represent the desire for

satisfying interpersonal relationships; and growth needs are about the desire for

continued personal growth and development. Secondly, while Maslow’s theory

argues that individuals progress up the hierarchy as a result of the satisfaction of

lower-order needs (a satisfaction–progression process), ERG theory includes a

‘frustration–regression’ principle, whereby an already satisfied lower-level need

can become activated when a higher-level need cannot be satisfied. Thus, if a

person is continually frustrated in their attempts to satisfy growth needs,

relatedness needs will again surface as key motivators. Thirdly, according to

Maslow, a person focuses on one need at a time. In contrast, ERG theory

contends that more than one need may be activated at the same time.

ERG theory categorises needs into existence, relatedness and growth needs.

Existence needs are about the desire for physiological and material wellbeing.

Relatedness needs are about the desire for satisfying interpersonal

relationships.

Growth needs are about the desire for continued personal growth and

development.

FIGURE 3.3 • Satisfaction–progression, frustration–

regression components of ERG theory

Source: Marc J Wallace, Jr, and Andrew D Szilagyi, Jr, Managing behavior in

organizations (Glenview, IL: Scott, Foresman, 1982).

ERG: the research

Research on ERG theory is relatively limited and includes disclaimers.42 One

of the earlier articles on this topic suggested interesting findings such as that

growth needs are higher for respondents with more highly educated parents

and women have lower strength of existence needs and higher strength of

relatedness needs than men.43 Another study from China argues that gender

makes some difference to motivational preferences using Alderfer’s approach

in a Chinese context.44 In regards to gender, males are more likely to be driven

by growth and existence needs. The same study also inferred complex links

between personality types and motivation using Alderfer’s and Maslow’s

theories.

Additional research is needed to shed more light on its validity, but the

supporting evidence on ERG theory is stronger than that for Maslow’s theory.

For now, the combined satisfaction–progression and frustration–regression

principles provide the manager with a more flexible approach to understanding

human needs than does Maslow’s strict hierarchy. Importantly, Alderfer’s

theory emphasises that performance constraints outside the control of the

individual (see figure 3.1), or innate disposition (such as lack of competence

or low intrinsic work motivation), may cause a decline in effort or negative

behaviour. Managers need to examine the workplace environment continually

to remove or reduce any organisational constraint that will restrict

opportunities for personal growth and development.

McClelland’s acquired needs theory

In the late 1940s the psychologist David McClelland distinguished three themes

or needs that he feels are important for understanding individual behaviour.

These needs are:

•

the need for achievement (nAch) — that is, the desire to undertake

something better or more efficiently, to solve problems or to master complex

tasks

•

the need for affiliation (nAff) — that is, the desire to establish and

maintain friendly and warm relations with others

•

the need for power (nPower) — that is, the desire to control others, to

influence their behaviour or to be responsible for others.

The need for achievement (nAch) is the desire to do something better, solve

problems or master complex tasks.

The need for affiliation (nAff) is the desire to establish and maintain friendly

and warm relations with others.

The need for power (nPower) is the desire to control others, influence their

behaviour and be responsible for others.

McClelland’s basic theory is that these three needs are acquired over time, as a

result of life experiences. People are motivated by these needs, which can be

associated with different work roles and preferences. The theory encourages

managers to learn how to identify the presence of nAch, nAff and nPower in

themselves and in others, and how to create work environments that are

responsive to the respective need profiles of different employees. One study

indicates that motivation has links to emotional intelligence. For example, those

with a higher perceived ability to regulate their emotions are more likely to be

motivated by achievement needs, while those who score highly in terms of being

able to appraise the emotions of others are more likely to be motivated by

affiliation needs.45

McClelland and his colleagues began experimenting with the Thematic

Apperception Test (TAT) as a way of measuring human needs.46 The TAT is a

projective technique that asks people to view pictures and write stories about

what they see. In one case, using projective techniques, McClelland tested three

executives on what they saw in a photograph of a man sitting down and looking

at family photos arranged on his work desk. In terms of nAch, McClelland

scored the stories given by the three executives as follows:47

•

person dreaming about family outing — nAch = + 1

•

person pondering new idea for gadget — nAch = + 2

•

person working on bridge-stress problem — nAch = + 4.

To provide a more complete profile, each picture would also be scored in terms

of nAff and nPower. Each executive’s profile would then be evaluated for its

motivational implications based on the three needs in combination.

One of the most important aspects of McClelland’s theorising is that he

challenges and rejects many other psychological theories that suggest the need

to achieve is a behaviour that is only acquired and developed during early

childhood. Alternatively, psychologists such as Erickson have supported a view

that the learning of achievement-motivated behaviour can only occur during

critical stages of a child’s development; if it is not obtained then it cannot be

easily learned or achieved during adult life.48 McClelland’s research contradicts

this viewpoint; he maintains that the need to achieve is a behaviour that an

individual can acquire through appropriate training in adulthood.

McClelland: the research

Research lends considerable insight into nAch in particular and includes some

interesting applications in developing nations. McClelland trained business

people in Kakinada, India, for example, to think, talk and act like high

achievers by having them write stories about achievement and participate in a

business game that encouraged achievement. The business people also met

with successful entrepreneurs and learned how to set challenging goals for

their own businesses. Over a two-year period following these activities, the

people from the Kakinada study engaged in activities that created twice as

many new jobs as those who did not receive training.49 Research on Chinese

entrepreneurship confirms McClelland’s view that the stronger a person’s

nAch, the greater likelihood that the person would be likely to start a

business.50

Other research also suggests that societal culture can make a difference in the

emphasis on nAch. Anglo-American countries such as Australia, the United

States, Canada and the United Kingdom (countries weak in uncertainty

avoidance and high in masculinity) tend to follow the high nAch pattern. In

contrast, strong uncertainty, high femininity countries, such as Portugal and

Chile, tend to follow a low nAch pattern. There are two especially relevant

managerial applications of McClelland’s theory. Firstly, the theory is

particularly useful when each need is linked with a set of work preferences

(table 3.1). Secondly, if these needs can truly be acquired, it may be possible

to acquaint people with the need profiles required to succeed in various types

of jobs. For example, McClelland found that the combination of a moderate to

high need for power and a lower need for affiliation enables people to be

effective managers at higher levels in organisations. Lower nAff allows the

manager to make difficult decisions without undue worry of being disliked.51

High nPower creates the willingness to have influence or impact on others,

though misuse of that power may result in sabotage by those mistreated or

prevented from rising to the top of the organisation.52

TABLE 3.1 • Work preferences of persons high in

need for achievement, affiliation and power

Individual needs

Woference

Example

High need for achievement

Individual responsibility; challenging but achievable goals; feedback

on performance

Field salesperson with a challenging quota and the opportunity to

earn individual bonus; entrepreneur

High need for affiliation

Interpersonal relationships; opportunities to communicate

Customer service representative; member of a work unit that is

subject to a group wage bonus plan

High need for power

Influence over other persons; attention; recognition

Formal position of supervisory responsibility; appointment as head

of special task force or committee

Herzberg’s two-factor theory

Frederick Herzberg’s research was based on in-depth interview techniques

learned during his training as a clinical psychologist. This interview approach —

called a ‘critical incident technique’ — has been the subject of considerable

debate among academics over many decades, but the findings of his theory have

been valuable. Herzberg began his research on motivation by asking workers to

comment on two statements:

1.

job.’

‘Tell me about a time when you felt exceptionally good about your

2.

‘Tell me about a time when you felt exceptionally bad about your

53

job.’

After analysing nearly 4000 responses to these statements (figure 3.4), Herzberg

and his associates developed the two-factor theory, also known as the

motivator–hygiene theory. They noticed that the factors identified as sources

of work dissatisfaction (subsequently called ‘dissatisfiers’ or ‘hygiene factors’)

were different from those identified as sources of satisfaction (subsequently

called ‘satisfiers’ or ‘motivator factors’).

The motivator–hygiene theory distinguishes between sources of work

dissatisfaction (hygiene factors) and satisfaction (motivators); it is also known

as the two-factor theory.

According to Herzberg’s two-factor theory, an individual employee could be

simultaneously both satisfied and dissatisfied because each of these two factors

has a different set of drivers and is recorded on a separate scale. According to

Herzberg’s measurement the two scales are:

FIGURE 3.4 • Herzberg’s two-factor theory: sources

of satisfaction and dissatisfaction as reported in 12

investigations

Source: Adapted & reprinted by permission of Harvard Business Review, Exhibit 1

from ‘One More time: How Do You Motivate Employees?’ by Frederick Herzberg, Sept–

Oct 87. © 2002 Harvard Business School Publishing Corporation; all rights reserved.

Effective managers have to achieve two distinct outcomes as now discussed: (1)

to maximise job satisfaction and (2) to simultaneously minimise job

dissatisfaction.

Satisfiers or motivator factors

To improve satisfaction, a manager must use motivator factors as shown on

the right side of figure 3.4. These factors are related to job content — that is,

what people do in their work. Adding these satisfiers or motivators to people’s

jobs is Herzberg’s link to performance. These cover such things as sense of

achievement, recognition and responsibility. According to Herzberg, when

these opportunities are absent, workers will not be satisfied and will not

perform well.

Motivators (motivator factors) are satisfiers that are associated with what

people do in their work.

Job content refers to what people do in their work.

Dissatisfiers or hygiene factors

Hygiene factors are associated with the job context; that is, they are factors

related to a person’s work setting. Improving working conditions (for

example, special offices and air conditioning) involves improving a hygiene,

or job context, factor. It will prevent people from being dissatisfied with their

work but will not make them satisfied. This can be an important distinction

from the motivator factors. Lambert55 argues that dissatisfiers are issues that

employees are unhappy about in their work but that are not necessarily the

causes of them leaving an organisation. Many organisations do put in effort to

address job context factors as the following examples show.

Hygiene (hygiene factors) are dissatisfiers that are associated with aspects

of a person’s work setting

Job context refers to a person’s work setting.

TABLE 3.2 • Sample hygiene factors found in work

settings

Hygiene factors

Examples

Organisational policies, procedures

Attendance rules

Holiday schedules

Grievance procedures

Performance appraisal methods

Working conditions

Noise levels

Safety

Personal comfort

Size of work area

Interpersonal relationships

Coworker relations

Customer relations

Relationship with boss

Quality of supervision

Technical competence of boss

Base salary

Hourly wage rate or salary

As table 3.2 shows, salary or money is included as a hygiene factor. This is

perhaps surprising and is discussed further in the next section.

Money: motivator or hygiene factor

Herzberg found that low salary makes people dissatisfied, but that paying

people more does not satisfy or motivate them. It is important to bear in mind

that this conclusion derives from data that found salary had considerable

cross-loading across both motivators and hygiene factors (see the bars that

cross the central vertical line at zero percentage frequency in figure 3.4).

Because most of the variance could be explained within the hygiene or job

context group of factors, Herzberg concluded that money was not a motivator.

New ideas are constantly being explored to link money and motivation. Direct

employee involvement in the financial future of the organisation is being

widely encouraged through Employee Share Ownership Programs (ESOPs).58

The extent to which these ESOPs are provided varies around the world59 and

may depend on factors such as favourable taxation. In Australia,

approximately 6 per cent of all employees have employee shares.60 Earlier

statistics suggested that differences in share ownership exist based on criteria

such as state, industry and occupation, working arrangements, and gender. For

example, managers and administrators have a higher proportion of employee

shares than the total (11.9 per cent) and full-time employees have more shares

than part-time employees (7.0 per cent compared to 3.4 per cent).61 Schemes

exist in organisations such as Wesfarmers, Foster’s and Eyecare Partners.62

It is difficult to explain the impact of such schemes on work motivation within

Herzberg’s framework, because these schemes have an impact on Herzberg’s

job content factors (such as responsibility and accountability) but also have a

direct impact on money and its link to work motivation and performance. The

link between money, ESOPs and work motivation remains complex and

inconclusive to date.

Some Australian studies have found that the link between money and

motivation also depends on other key factors such as the work status of the

employee. One study found that casual workers employed on a part-time basis

placed a higher value on job security than on monetary reward. The

implications of this finding are far reaching because the growth in the parttime workforce in Australia and New Zealand is far greater than the growth of

the full-time workforce.

Herzberg: the research and practical implications

Organisational behaviour scholars debate the merits of the two-factor theory.63

While Herzberg’s continuing research and that of his followers support the

theory, some researchers have used different methods and are unable to

confirm the theory. It is therefore criticised as being method-bound — that is,

supportable only by applying Herzberg’s original method. This is a serious

criticism because the scientific approach requires that theories be verifiable

when different research methods are used. The critical incident method used

by Herzberg may have resulted in respondents generally associating good

times in their jobs with things under their personal control, or for which they

could give themselves credit. Bad times, on the other hand, were more often

associated with factors in the environment under the control of management.

Herzberg’s theory has also met with other criticisms.

1.

The original sample of scientists and engineers probably is not

representative of the working population.

2.

The theory does not account for individual differences (for example,

the similar impact of pay regardless of gender, age and other important

differences).

3.

The theory does not clearly define the relationship between satisfaction

and motivation.64

Such criticisms may contribute to the mixed findings from research conducted

outside the United States. In New Zealand, for example, supervision and

interpersonal relationships have been found to contribute significantly to

satisfaction and not merely towards reducing dissatisfaction. And certain

hygiene factors have been cited more frequently as satisfiers in Panama, Latin

America and a number of countries other than the United States. In contrast,

earlier evidence from countries such as Finland tends to confirm US results.65

A study of a Norwegian company, Telenor, suggested the physical

environment (incorporating the aspects of art, design and architecture) could

be a motivator — since the pleasantness of the physical environment might

impact on the mood, the wellbeing and the inspiration of workers.66 This

finding appears to work against the idea that ‘working conditions’ constitute

hygiene factors. The same Norwegian study also indicated that respondents to

their survey seemed to find it hard to distinguish between motivation and

satisfaction, presumably accepting the two as related. In view of globalising

workforces, these distinctions may have significant importance for managers

endeavouring to motivate their employees.

However, Herzberg’s theory does have value. For example, it may help to

identify why a focus on job environment factors (such as special office

fixtures, piped-in music, comfortable lounges for breaks and high base

salaries) often do not motivate. It also highlights the value of job design and

motivation as discussed in chapter 5.

4 LEARNING OBJECTIVE

Process theories of motivation

Process theories

As useful as they are, content theories still emphasise the ‘what’ aspect of

motivation — that is, ‘If I have a security deficiency, I try to reduce or remove it’.

They do not emphasise the thought processes concerning ‘why’ and ‘how’ people

choose one action over another in the workplace. For this, we must turn to process

motivation theories. Two well-known process theories are equity theory and

expectancy theory.

Equity theory

Equity theory is based on the phenomenon of social comparison and is best

known through the writing of J Stacy Adams.67 Adams argues that when people

gauge the fairness of their work outcomes compared with those of others, felt

inequity is a motivating state of mind. That is, when people perceive inequity in

their work, they experience a state of cognitive dissonance, and they will be

aroused to remove the discomfort and to restore a sense of felt equity to the

situation. Inequities exist whenever people feel that the rewards or inducements

they receive for their work inputs or contributions are unequal to the rewards

other people appear to have received for their inputs. For the individual, the

equity comparison or thought process that determines such feeling is:

Equity theory presents the idea that motivation is affected when people feel

that work outcomes are unfair or inequitable, due to social comparison in the

workplace.

Resolving felt inequities

Felt negative inequity exists when an individual feels that they have received

relatively less than others have in proportion to work inputs. Felt positive

inequity exists when an individual feels that they have received relatively

more than others have.

Felt negative inequity exists when individuals feel they have received

relatively less than others have in proportion to work inputs.

Felt positive inequity exists when individuals feel they have received

relatively more than others have.

Both felt negative and felt positive inequity are motivating states. When either

exists, the individual will likely engage in one or more of the following

behaviours to restore a sense of equity:

1.

change work inputs (for example, reduce performance efforts)

2.

change the outcomes (rewards) received (for example, ask for a raise)

3.

leave the situation (for example, quit)

4.

change the comparison points (for example, compare self with a

different coworker)

5.

psychologically distort the comparisons (for example, rationalise that

the inequity is only temporary and will be resolved in the future)

6.

act to change the inputs or outputs of the comparison person (for

example, get a coworker to accept more work).

Equity theory predicts that people who feel either under-rewarded or overrewarded for their work will act to restore a sense of equity.

Adams’s equity theory: the research

The research of Adams and others, accomplished largely in laboratory

settings, lends tentative support to this prediction.68 The research indicates that

people who feel overpaid (felt positive inequity) increase the quantity or

quality of their work, while those who feel underpaid (felt negative inequity)

decrease the quantity or quality of their work. The research is most conclusive

about felt negative inequity. It appears that people are less comfortable when

they are under-rewarded than when they are over-rewarded.

Managing the equity dynamic

Figure 3.5 shows that the equity comparison intervenes between a manager’s

allocation of rewards and their impact on the work behaviour of staff. Feelings

of inequity are determined solely by the individual’s interpretation of the

situation.

FIGURE 3.5 • The equity comparison as an

intervening variable in the rewards, satisfaction and

performance relationship

Thus, it is incorrect to assume all employees in a work unit will view their

annual pay rise as fair. It is not how a manager feels about the allocation of

rewards that counts; it is how the recipients perceive the rewards that will

determine the motivational outcomes of the equity dynamic. Managing the

equity dynamic therefore becomes quite important to the manager, who strives

to maintain healthy psychological contracts — that is, fairly balanced

inducements and contributions — among staff.

Rewards that are received with feelings of equity can foster job satisfaction

and performance. In contrast, rewards that are received with feelings of

negative inequity can damage these key work results. The burden lies with the

manager to take control of the situation and make sure that any negative

consequences of the equity comparisons are avoided, or at least minimised,

when rewards are allocated. ‘The effective manager 3.1’ below shows how

you can deal with these concerns.

THEEffectiveManager 3.1: Steps for

managing the equity process

• Recognise that an employee is likely to make an equity comparison

whenever especially visible rewards, such as pay, promotions and so on,

are being allocated.

•

Anticipate felt negative inequities.

• Communicate to each individual your evaluation of the reward, an

appraisal of the performance on which it is based, and the comparison

points you consider to be appropriate.

Managing the equity dynamic across cultures can become very complex.

Western expatriates working in multinational corporations typically adopt an

individual frame of reference when making equity comparisons. For local

employees in Eastern cultures, the value placed on rewards and the weighting

attributed to a specific outcome may vary considerably from Western norms.

The group, not the individual, is the major point of reference for such equity

comparisons and if a multinational corporation tries to motivate by offering

individualised rewards, employees may not respond as expected.69

Expectancy theory

Victor Vroom’s expectancy theory77 seeks to predict or explain the task-related

effort expended by a person. The theory’s central question is: ‘What determines

the willingness of an individual to exert personal effort to work at tasks that

contribute to the performance of the work unit and the organisation?’

Figure 3.6 illustrates the managerial foundations of expectancy theory.

Individuals are viewed as making conscious decisions to allocate their behaviour

towards work efforts and to serve self-interests. The three key terms in the

theory are as follows:

1.

Expectancy: the probability that the individual assigns to work effort

being followed by a given level of achieved task performance. Expectancy

would equal ‘0’ if the person felt it was impossible to achieve the given

performance level; it would equal ‘1’ if a person was 100 per cent certain that

the performance could be achieved.

Expectancy is the probability that the individual assigns to work effort

being followed by a given level of achieved task performance.

2.

Instrumentality: the probability that the individual assigns to a given

level of achieved task performance leading to various work outcomes that are

rewarding for them. Instrumentality also varies from ‘1’ (meaning the reward

outcome is 100 per cent certain to follow performance) to ‘0’ (indicating that

there is no chance that performance will lead to the reward outcome). (Strictly

speaking, Vroom’s treatment of instrumentality would allow it to vary from

−1 to +1. We use the probability definition here and the 0 to 1 range for

pedagogical purposes; it is consistent with the basic instrumentality notion.)

Instrumentality is the probability that the individual assigns to a level of

achieved task performance leading to various work outcomes.

3.

Valence: the value that the individual attaches to various work reward

outcomes. Valences form a scale from −1 (very undesirable outcome) to +1

(very desirable outcome).

Valence represents the values that the individual attaches to various work

outcomes.

Expectancy theory argues that work motivation is determined by individual

beliefs about effort–performance relationships and the desirability of various

work outcomes from different performance levels. Simply, the theory is based

on the logic that people will do what they can do when they want to.78 If you

want a promotion and see that high performance can lead to that promotion, and

that if you work hard you can achieve high performance, you will be motivated

to work hard. Estee Lauder, a leading skin care, fragrance and hair care

company, is an example of a business where promotion within is well

entrenched, thereby increasing employee belief that performance may lead to

promotion.

Expectancy theory argues that work motivation is determined by individual

beliefs about effort–performance relationships and the desirability of various

work outcomes from different performance levels.

Multiplier effects and multiple outcomes

Vroom posits that motivation (M), expectancy (E), instrumentality (I) and

valence (V) are related to one another by the equation: M = E × I × V.

FIGURE 3.6 • Expectancy theory terms in a

managerial perspective

This relationship means that the motivational appeal of a given work path is

sharply reduced whenever any one or more of these factors approaches the

value of zero. Conversely, for a given reward to have a high and positive

motivational impact as a work outcome, the expectancy, instrumentality and

valence associated with the reward must all be high and positive.

Suppose a manager is wondering whether the prospect of earning a merit pay

rise will be motivational to a subordinate. Expectancy theory predicts that

motivation to work hard to earn the merit pay will be low if the person:

1.

feels they cannot achieve the necessary performance level (expectancy)

2.

is not confident a high level of task performance will result in a high

merit pay rise (instrumentality)

3.

places little value (valence) on a merit pay increase

4.

experiences any combination of these.

Expectancy theory is able to accommodate multiple work outcomes in

predicting motivation. As shown in figure 3.7, the outcome of a merit pay

increase may not be the only one affecting the individual’s decision to work

hard. Relationships with coworkers may also be important, and they may be

undermined if the individual stands out from the group as a high performer.

Although merit pay is both highly valued and considered accessible to the

individual, its motivational power can be cancelled out by the negative effects

of high performance on the individual’s social relationships with coworkers.

One of the advantages of expectancy theory is its ability to help managers

account for such multiple outcomes when trying to determine the motivational

value of various work rewards to individual employees.

FIGURE 3.7 • An example of individual thought

processes, as viewed by expectancy theory

Vroom: managerial implications

The managerial implications of Vroom’s expectancy theory are summarised in

table 3.3. Expectancy logic argues that a manager must try to understand

individual thought processes, then actively intervene in the work situation to

influence them. This includes trying to maximise work expectancies,

instrumentalities and valences that support the organisation’s production

purposes. In other words, a manager should strive to create a work setting in

which the individual will also value work contributions serving the

organisation’s needs as paths towards desired personal outcomes or rewards.

TABLE 3.3 • Managerial implications of expectancy

theoryrm

Expectancy theory might also be considered in the context of uncertainty in

the work-place. It also suggests that managers need to understand the

individual expectancy and instrumentality links for all workers. Although

individuals will always be unique in their motivation, there may be new

cohorts of workers in the organisation (such as those staying past retirement

age and the Gen X and Gen Y employees) about whom generalisations may be

made.

Vroom: the research

There is a great deal of research on expectancy theory, and good review

articles are available.80 Although the theory has received substantial support,

specific details (such as the operation of the multiplier effect) remain subject

to question. Rather than charging that the underlying theory is inadequate,

researchers indicate that problems of method and measurement may cause

their inability to generate more confirming data. Thus, while awaiting the

results of more sophisticated research, experts seem to agree that expectancy

theory is a useful insight into work motivation.

One of the more popular modifications of Vroom’s original version of the

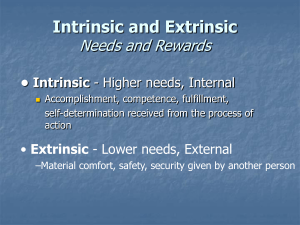

theory distinguishes between extrinsic and intrinsic rewards as two separate

types of possible work outcomes.81 Extrinsic rewards are positively valued

work outcomes that the individual receives from some other person in the

work setting. An example is pay. Workers typically do not pay themselves

directly; some representative of the organisation administers the reward. In

contrast, intrinsic rewards are positively valued work outcomes that the

individual receives directly as a result of task performance; they do not require

the participation of another person. A feeling of achievement after

accomplishing a particularly challenging task is one example. The distinction

between extrinsic and intrinsic rewards is important because each type

demands separate attention from a manager seeking to use rewards to increase

motivation. We discuss these differences more thoroughly in chapters 4 and 5.

Extrinsic rewards are positively valued work outcomes that the individual

receives from some other person in the work setting.

Intrinsic rewards are positively valued work outcomes that the individual

receives directly as a result of task performance.

5 LEARNING OBJECTIVE

Integrating content and process motivation theories

Integrating content and process motivation theories

Each of the theories presented in this chapter is potentially useful for the manager.

Although the equity and expectancy theories have special strengths, current

thinking argues for a combined approach that points out where and when various

motivation theories work best.82 Thus, before leaving this discussion, we should

pull the content and process theories together into one integrated model of

individual performance and satisfaction.

First, the various content theories have a common theme, as shown in figure 3.8.

Content theorists disagree somewhat as to the exact nature of human needs, but

they do agree that:

The manager’s job is to create a work environment that responds positively to

individual needs. Poor performance, undesirable behaviours and/or decreased

satisfaction can be partly explained in terms of ‘blocked’ needs, or needs that are

not satisfied on the job. The motivational value of rewards (intrinsic and extrinsic)

can also be analysed in terms of ‘activated’ needs to which a given reward either

does or does not respond. Ultimately, managers must understand that individuals

have different needs and place different importance on different needs. Managers

must also know what to offer individuals to respond to their needs and to create

work settings that give people the opportunity to satisfy their needs through their

contributions to task, work unit and organisational performance.

FIGURE 3.8 •

theories

Comparison of content motivation

Figure 3.9 is a model that goes further to integrate content and process theories.

The model, as proposed by Lyman W Porter and Edward E Lawler, is an

extension of Vroom’s original expectancy theory.83 The figure is based on the

foundation of the individual performance equation (see chapter 2). Individual

attributes and work effort, and the manager’s ability to create a work setting that

positively responds to individual needs and goals all affect performance. Whether

a work setting can satisfy needs depends on the availability of rewards (extrinsic

and intrinsic). The content theories enter the model as the manager’s guide to

understanding individual attributes and identifying the needs that give

motivational value to the various work rewards allocated to employees. Research

has linked individual attributes such as personality with motivation in terms of

achievement factors and intrinsic and extrinsic motivation. For example, highly

conscientiousness employees are likely to work well and achieve in environments

high in intrinsic motivation opportunities.84 Managers are also interested in

promoting high levels of individual satisfaction as a part of their concern for

human resource maintenance. You may recall that we concluded our chapter 2

review of the satisfaction–performance controversy by noting that when rewards

are allocated on the basis of past performance (that is, when rewards are

performance contingent), they can cause both future performance and satisfaction.

Motivation can also occur when job satisfactions result from rewards that are felt

to be equitably allocated. When felt negative inequity results, satisfaction will be

low and motivation will be reduced. Thus, the integrated model includes a key

role for equity theory and recognises job performance and satisfaction as separate,

but potentially interdependent, work results.85

FIGURE 3.9 • Predicting individual work

performance and satisfaction: an integrated model

Other perspectives on motivation

In recent years more work has developed to explain other dimensions that

contribute to our understanding of motivation. These extend beyond what is

traditionally explained by content and process theories. A complex interplay of

factors can affect motivation. Some particular ideas collated by Humphreys

include the following:

• the follower’s self-concept, be influenced by transformational leaders (see

chapter 11) who are able to increase follower motivation by maintaining and

enhancing their self-concept

• through maturity and experience, individuals experience motivational

development — they are likely to engage in behaviours that relate to status,

extrinsic rewards and personal fulfilment

• there is a relationship between follower self-efficacy and performance with

self-efficacy contributing to the motivation aspect of the performance equation

• altering task complexity can affect one’s work identity and self-image both

negatively and positively and be a moderating variable in motivation

• leaders have responsibilities to establish and develop a relationship for goal

success and individual growth with the subordinate so they are jointly

responsible to each other

• there must be congruency between a leader’s communication and a follower’s

values, and/or between the leader’s focus and the follower’s identity and values.

Leader-follower congruency may affect leader’s attempt to enhance a follower’s

self-concept

• some work indicates that different personalities can be explained as different

temperaments. Temperament can impact upon how individuals are motivated,

their likely satisfaction and goal-directed behaviour.86

6 LEARNING OBJECTIVE

Other perspectives on motivation

Collectively, such factors can contribute to a congruent temperament model which

suggests that motivation is enhanced when the leader can understand the

employee, and respond appropriately with behaviours that are congruent with the

follower’s temperament and perspective.

There has also been quite a bit of work done researching why people often offer

their services voluntarily or engage in altruistic deeds without having any

anticipated rewards (intrinsic or extrinsic). Personal value systems and the idea of

self-concept, underlie this approach. Self-concept is the concept that individuals

have of themselves as physical, social and spiritual or moral beings.

Self-concept is the concept that individuals have of themselves as physical,

social and spiritual or moral beings.

The self-concept approach comes from personality theory. It focuses on using the

concept of the self as an underlying force that motivates behaviour, that gives it

direction and energy and sustains it. Self-concept is derived from many influences

including family, social identity and reference groups, education and experience.

Generally speaking, these aspects of personality are a guide to our behaviour and

help us to decide what to do in specific situations. So, for example, a young

person may choose to study medicine or dentistry at university, or to enter the

family trade, because that is what was always expected of them and has therefore

become an important part of their identity. Rewards such as money and status may

be secondary considerations. Many acts are done out of a sense of responsibility,

integrity or even humour, which relate to the self-concept aspect of personality.87

This sort of approach would help to explain the nurse who waits with the relatives

of a critically injured patient for hours after his shift is completed; or the person

who works the shift of a friend who is studying for exams.

In contrast to a focus on needs or cognitive thought processes to explain

motivation, the self-concept approach relies on other ways of

understanding motivation to explain the full range of motivated behaviour. People

may also draw on the values they hold, and the way that these values are a guide

to behaviours that seem right or appropriate for them. For example, people

internalise values that are espoused by the professional group (or the organisation)

to which they belong. Behaviours consistent with such values might include

saving lives and property at considerable personal risk, exposing unethical

financial practices despite censure from management, or facing personal hardship.

A study by Camilleri found that there might be an altruistic motivation

relationship between some public servants’ commitment to serving the public

interest and their sense of compassion. The relationship was evident for married

public servants with children and bachelors but not for those married without

children, or without children at home.88 Having identified content and process

theories and an integrated model of these two approaches, as well as considering

the ideas of self-efficacy, self-concept, personal values and temperament in

motivation, it is worth reflecting on how managers may be able to understand and

implement these concepts in the workplace.

Summary

Motivating and empowering today’s workforce

1 LEARNING OBJECTIVE

In the contemporary world, a key challenge is to motivate and empower workers

towards productive performance. With an ageing population, when there are

labour shortages and with mobile workforces, organisations need to understand

how to motivate and empower employees in order to attract and retain them and

to enhance performance.

Difference between content and process

motivation theories

2 LEARNING OBJECTIVE

There are two main types of motivational theories — content and process.

Content theories examine the needs that individuals have. Their efforts to satisfy

those needs are what drive their behaviour. Process theories examine the thought

processes that people have in relation to motivating their behaviour.

Content theories of motivation

3 LEARNING OBJECTIVE

The content theories of Maslow, Alderfer, McClelland and Herzberg emphasise

needs or motives. They are often criticised for being culturally biased, and

caution should be exercised when applying these theories in non-Western

cultures.

Maslow’s hierarchy of needs theory arranges human needs into a five-step

hierarchy: physiological, safety, social (the three lower-order needs), esteem and

self-actualisation (the two higher-order needs). Satisfaction of any need

activates the need at the next higher level, and people are presumed to move step

by step up the hierarchy. Alderfer’s ERG theory has modified this theory by

collapsing the five needs into three: existence, relatedness and growth. Alderfer

also allows for more than one need to be activated at a time and for a

frustration–regression response. McClelland’s acquired needs theory focuses on

the needs for achievement (nAch), affiliation (nAff) and power (nPower). The

theory argues that these needs can be developed through experience and

training. Persons high in nAch prefer jobs with individual responsibility,

performance feedback and moderately challenging goals. Successful executives

typically have a high nPower that is greater than their nAff. Herzberg’s twofactor theory treats job satisfaction and job dissatisfaction as two separate issues.

Satisfiers, or motivator factors such as achievement, responsibility and

recognition, are associated with job content. An improvement in job content is

expected to increase satisfaction and motivation to perform well. In contrast,

dissatisfiers, or hygiene factors such as working conditions, relations with

coworkers and salary, are associated with the job context. Improving job context

does not lead to more satisfaction but is expected to reduce dissatisfaction.

Process theories of motivation

4 LEARNING OBJECTIVE

Process theories emphasise the thought processes concerning how and why

people choose one action over another in the workplace. Process theories focus

on understanding the cognitive processes that act to influence behaviour.

Although process theories can be very useful in explaining work motivation in

cross-cultural settings, the values that drive such theories may vary substantially

across cultures and the outcomes may differ considerably.

Equity theory points out that people compare their rewards (and inputs) with

those of others. The individual is then motivated to engage in behaviour to

correct any perceived inequity. At the extreme, feelings of inequity may lead to

reduced performance or job turnover. Expectancy theory argues that work

motivation is determined by an individual’s beliefs concerning effort–

performance relationships (expectancy), work–outcome relationships

(instrumentality) and the desirability of various work outcomes (valence).

Managers, therefore, must build positive expectancies, demonstrate

performance-reward instrumentalities, and use rewards with high positive

valences in their motivational strategies.

Integrating content and process motivation

theories

5 LEARNING OBJECTIVE

The content theories can be compared, with some overlap identified. An

integrated model of motivation builds from the individual performance equation

and combines the content and process theories to show how well-managed

rewards can lead to high levels of both individual performance and satisfaction.

Other perspectives on motivation

6 LEARNING OBJECTIVE

Other theories go beyond content and process theories to draw links with

personality theory, leadership, individual values, self-concept and self-efficacy.

Such theories tend to place a lot of emphasis on leader responsibility for

motivation and on the complexity of motivation. Theories that focus on selfconcept and personal values seek to describe motivation as a desire that is

derived from a person’s self-concept. This self-concept guides individual

behaviour.

(Wood. Organisational Behaviour: Core Concepts and Applications, 2nd Edition.

John Wiley & Sons Australia, 10.10).

Preparation

Complete the following ‘Motivators or hygienes’ assessment before coming

to class.

Most workers want job satisfaction. The following 12 job factors may

contribute to job satisfaction. Rate each according to how important it is to

you. Place a number on a scale of 1 to 5 on the line before each factor.

______ 1. An interesting job

______ 2. A good boss

______ 3. Recognition and appreciation for the work I do

______ 4. The opportunity for advancement

______ 5. A satisfying personal life

______ 6. A prestigious or status job

______ 7. Job responsibility

______ 8. Good working conditions (nice office)

______ 9. Sensible company rules, regulations, procedures and policies

______ 10.

The opportunity to grow through learning new things

______ 11.

A job I can do well and at which I can succeed

______ 12.

Job security

To determine if hygienes or motivators are important to you, place your

scores below.