2 Classroom Observation Tasks

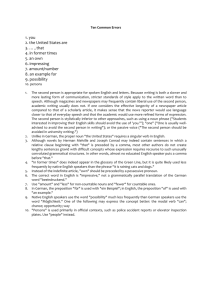

advertisement