Chapter 4 - Economics

advertisement

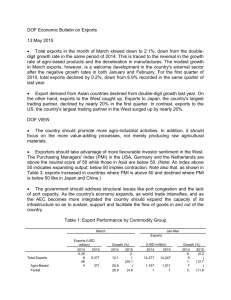

1 Lecture 3 Resources and Trade: The Heckscher-Ohlin Model Introduction The Ricardian model has two short comings: First, it does not allow for the study of the effects of trade on income distribution; everyone gains from trade in the Ricardian model, while we know in the real world some people lose from trade. Second, the Ricardian model does not explain differences in labor productivity amongst countries. In the real world, part of labor productivity is due to the resource endowment. Labor productivity is higher in countries with higher capital or land endowments. In addition the constant opportunity cost is not a desirable property in the Ricardian model. This property leads to compete specialization which we do not observe very often in the real world. Swedish Econ History Eli Heckscher (article 1919) and his student Bertil Ohlin who developed these idea in his 1924 dissertation Explained trade on the bases of difference in resource endowment Shows that comparative advantage is influenced by: • Relative factor abundance (refers to countries) • Relative factor intensity (refers to goods) Is also referred to as the factor-proportions theory The Heckscher-Ohlin model allows studying the impact of trade on income distribution and it partially explains labor productivity based on capital endowment The main result of H-O model is expressed in H-O theorem. This theorem states that for example a capital-abundant country exports the capital-intensive good while the laborabundant country exports the labor-intensive good. Here's why: – A capital-abundant country => higher relative supply of K-intensive goods – => Lower relative price of k-intensive good before trade – The H-O theorem demonstrates that differences in resource endowments (as defined by national abundances) can be a reason for international trade to occur. 2 Assumptions H-O Model Two goods: An economy can produce two goods, Shoes (QS ), Computers (QC ) Two Countries: Home and Foreign Two Factors of Production: • The production of these goods requires two inputs labor L and Capital K. • Supply of the two inputs are given and fixed • The two factors are perfectly mobile domestically (a long run view is taken here) within countries and immobile between countries. Technology • Same technology in both countries. • Constant Returns to Scale (CRS) production functions: QS = QS(LS, KS) QC = QC(LC, KC) Production of computer is capital-intensive and production of shoe is labor-intensive in both countries. LC /KC < LS /KS , (e.g., wage share of production cost in higher in shoes compared to computers) These two curves slope down just like regular demand curves, but in this case, they are relative demand curves for labor (i.e., demand for labor divided by demand for capital). That is the labor/labor content in shoes are larger than computers. Perfect competition prevails in all markets and no transportation cost. The two countries differ only in their factor endowments (same tastes, same tech) 3 Production Possibility Frontier (PPF): Increasing Opportunity Economy Opp Cost of Shoes in terms of Computer increases as more computers are produced. QS Opp. Cost of Computers in terms of Shoes = Slope = -PC/PS A 1/2 A E 1/2 B B QC Why do we get this result? Because resources are not equally suitable for production of all good! Why PPF represents increasing opportunity cost? Why PPF is not a straight line? To see this consider will show that can do better than E (above the line) in the figure above: A = QS produced if all resources are allocated to shoes production B = QC produced if all resources are allocated to computer production E = (½ A and ½ B) if ½ of all the resources (½ of all K and ½ of all L) are allocated to shoes and the other half to computers Can do better than E (North East of E up to the PPF), if in shifting resources from Kintensive computers to L-intensive shoes if less than ½ capital and more than ½ Labor is released to the shoes sector. 4 PPF, Resource Endowment and Technology In general PPF of two countries can be different for reasons of resource endowment or technology. Countries with identical resources and technology have identical PPF. To see how PPF’s of two countries might be different consider the following exercises: a) an increase in Labor endowment, b) an increase in capital endowment and c) an improvement in technology of production. QS QS QC (a) An increase in Labor Endowment and the shift in PPF QC (b) An increase in Capital Endowment and the shift in PPF QS (c) An unbiased improvement in the technology of production QC 5 Equilibrium before International Trade QS G QS1 A U Slope = - PC/PS G’ QC1 QC Production and Consumption in absence of International Trade In absence of international trade the production mix of computers and shoes depends on domestic demand. In this economy demand is such that production takes place at point A on PPF, where PPF is tangent to the highest indifference curve. The slope of the PPF at the point of tangency determines domestic relative price of computers: PC/PS. Note that this line, GG’ also measures the value of mix of production at point A. That is GG’ represents GDP when production takes place at point A. To see this notice that: GDP = PC QC1+PS QS1 Heckscher-Ohlin Theorem: Each country will export the good that uses its abundant factor intensively. To show this let’s make the following assumptions: • There are two countries (Home and Foreign) with: – Same tastes & Same technology – And Different factor endowment • In particular let’s assume L/K < L*/K* – i.e. Home is Capital Abundant, Foreign is Capital Scarce Then under these assumptions the theorem implies that Home country exports capital intensive computers and imports labor intensive shoes. Before trade Home production and consumption takes place at point A at autarky price ratio of PC/PS. Before trade Foreign production and consumption takes place at point A* at autarky price ratio of P*C/P*S . Since Home is relatively Labor scarce (capital abundant) its autarky relative price of Computer would be lower that that of the Foreign country PC/PS<P*C/P*S. 6 Before Trade Production and Consumption in Home and Foreign Country QS Slope = -PC/PS Slope = -P*C/P*S Q*S A* A U* U (a) Home Country QC (b) Foreign Country Q*C Once trade opens up Home will export Computers and Foreign will export Shoes. International prices will be somewhere between the autarky prices of the two countries: PC/PS < (PC/PS)W<P*C/P*S Post-Trade: Production and Consumption of Home and Foreign Country QS Slope = (PC/PS)W Slope = (PC/PS)W Q*S B* • C • B A* U2 C* U2* U A (a) Home Country QC (b) Foreign Country Q*C At (PC/PS) < (PC/PS)W < P*C/P*S capital abundant Home exports capital intensive computer and Labor abundant Foreign exports Labor intensive shoes. Aggregate Economic Efficiency – The H-O model demonstrates that when countries move to free trade, they will experience an increase in aggregate efficiency. – The change in prices will cause a shift in production of both goods in both countries. – Each country will produce more of its export good and less of its import goods. – Unlike the Ricardian model, however, neither country will necessarily specialize in production of its export good. 7 – – – – – As a result of the production shifts though, productive efficiency in each country will improve. Also, due to the changes in prices, consumers, in the aggregate will experience an improvement in consumption efficiency. In other words, national welfare will rise for both countries when they move to free trade. However, this does not imply that everyone benefits. Later we will show some factor owners will experience an increase in their real incomes while others will experience a decrease in their factor incomes. Trade will generate winners and losers. The increase in national welfare essentially means that the sum of the gains to the winners will exceed the sum of the losses to the losers. For this reason economists often apply the compensation principle. The compensation principle states that as long as the total benefits exceed the total losses in the movement to free trade, then it must be possible to redistribute income from the winners to the losers such that everyone has at least as much as they had before trade liberalization occurred. Testing the Heckscher-Ohlin Theorem: Leontief’s Paradox In 1953 Wassily Leontief performed the first test of the Heckscher-Ohlin theorem, using data for the United States from 1947. Leontief measured the amounts of labor and capital used in all industries needed to produce $1million of U.S. exports and to produce $1 million of imports into the U.S. His results are shown in Table below. Table 4.1 Leontief’s Test Leontief first measured the amount of capital and labor required in the production of $1 million worth of U.S. exports. Leontief measured the labor and capital used directly in the production of final good exports in each industry, as well as indirectly the labor and capital used in the industries that produced the intermediate inputs used in making the exports. From the Table we see that $2.55 million worth of capital was used to produce $1 million of exports. What is being measured is the capital stock. Only the annual depreciation on this stock was actually used to produce exports that year. For labor, 182 person-years were used to produce the exports. Taking the ratio of these, we find that each person employed (directly or indirectly) in producing exports was working with $14,000 worth of capital. 8 Leontief used the data on U.S. technology to calculate estimated amounts of labor and capital used in imports from abroad. o Does this invalidate Leontief’s test of the Heckscher-Ohlin model? Not really, because the Heckscher-Ohlin model assumes that technologies are the same across countries, so Leontief is building this assumption into the calculations needed to test the theorem. $3.1 million of capital and 170 person-years were used in the production of $1 million worth of U.S. imports, so the capital-labor ratio for imports was $18,200 per worker. This amount exceeds the capital-labor ratio for exports, of $14,000 per worker. From the Heckscher-Ohlin theorem Leontief expected that the United States would export capital-intensive goods and import labor-intensive goods. But he found was just the opposite: the capital-labor ratio for U.S. imports was higher than the capital-labor ratio found for U.S. exports! This finding contradicted the Hecksher-Ohlin theorem, and came to be called “Leontief’s paradox.” A wide range of explanations have been offered for Leontief’s paradox, such as: U.S. and foreign technologies are not the same, as HO theorem and Leontief assumed; By focusing only on labor and capital, Leontief ignored land abundance; Should have distinguished skilled versus unskilled labor (since it would not be surprising to find that U.S. exports are intensive in skilled labor); The data for 1947 may by unusual, The U.S. was not engaged in completely free trade, as the H-O model assumes. Many Goods, Factors and Countries Measuring Factor Abundance: When there are more than two factors and two countries, how should we measure factor abundance? With only two factors of production, we said that a country is abundant in a factor if the amount of that factor found in the country, relative to the other factor, is greater than the same ratio abroad. For example, Foreign is abundant in labor if L* / K* L/ K, as we assumed earlier in the chapter. This definition of factor abundance applies when there are two factors of production. What happens to our descriptions of factor abundance when we include land, or distinguish various types of labor, so there are more than two factors? In that case we need to give a more general definition of factor abundance, as illustrated by the data in Figure 4.6. 9 Figure 4.6: Shares of World Factor Endowments Because the U.S. has 24% of the world’s capital, and 21.6% of the world GDP, we can conclude that the U.S. is (slightly) abundant in physical capital. Japan has 13.3% of the world’s capital and 7.5% of the world’s GDP, so it is also abundant in capital, as is Germany. The opposite holds for the China, India and the rest of the world, however; their shares of world capital are less than their share of GDP. We compare the country’s share of that factor with its share of world GDP: if its share of a factor exceeds its share of world GDP, then we conclude that the country is abundant in that factor; if its share of world GDP exceeds its share in a certain factor, then we conclude that the country is scarce in that factor. For example we see that the United States is abundant in R&D scientists (with 26.1% of the world’s total as compared to 21.6% of the world GDP) and also skilled labor, but is scarce in semiskilled or illiterate labor. India was scares in R&D scientists (with 2.5% of world R&D compared with 5.5% of the world GDP) but abundant in skilled labor, semiskilled labor, and illiterate labor. US was scares in arable land (12.6% of world’s total land compared with 21.6% or world’s GDP). US exports agricultural products and from the H-O theorem we would expect US to be land abundant. 10 China was abundant in R&D scientists! It had 14% of world’s R&D scientists, as compared with 11.2% of world’s GDP in 2000. This observation also contradicts H-O as we do not think of China as exporting highly skilled-intensive products. These observations make us wonder whether an R&D scientist or an acre of land has the same productivity in all countries. Differing Productivities Across Countries One explanation for the Leontief paradox would be that labor is highly productive in the United States, and less productive in the rest of the world. If that is the case, then the effective labor force in the United States, which is defined as the labor force times their productivity, is actually much higher than we would think by just counting people. In that case, perhaps the United States is abundant in (skilled) labor after all, and it should be no surprise that it is exporting labor-intensive products. Figure 4.7 “Effective” Factor Endowments, 2000 Once we allow factors of production to differ in their productivities across countries then we define: Effective factor endowment = Actual factor endowment * Factor productivity 11 Modified H-O theorem: Each country exports the good that uses its abundant effective factor intensively Figure 4.9 Differences in Wages and Productivities Across Countries Figure 4.9 shows the estimated labor productivities across countries, and their wages, relative to the United States in 1990. Notice that labor productivity and wages are highly correlated across countries: the points roughly line up along the 45 degree line. This close connection between wages and labor productivity 12 Effects of Trade on Factor Prices An increase in the relative price of computers leads to an increase in the production of computers relative to shoes. In Figure below this is illustrated by a movement from production mix A to B. PC/PS↑ QC/QS ↑ An increase in the relative production of computers leads to an increase in demand for capital relative to labor (a reduction in relative demand for labor). QC/QS ↑ Economy-Wide Relative Demand for Labor ↓=> W/R↓ Solper-Samuelson Theorem: An increase in the price of a product will increase the (real) price of the factor used intensively in the production of that product and a reduction in the (real) price of the other factor. Proof: Suppose we have two products shoes and computers, shoes are labor intensive and computers capital intensive now suppose relative price of computers go up Pc/Ps↑ this will lead to a change in production mix (more Qc and less Qs) Qc/Qs↑. That leads to a reduction of economy-wide relative demand for labor which in turn reduces relative price of labor (W/R↓). To show the effect on real W and R note that lower relative demand for labor implies higher L-K-ratio in both sectors in face of higher capital employed in computers (due to higher Qc) and lower capital employed in shoes (due to lower Qs). 13 Lower L-K ratios implies lower MPL=W/Ps and higher MPK=R/Pc. That is lower real wage rate and higher real return on capital. The relationship between Goods-Prices, Factor-Prices, and Factor-Contents In Stolper-Samuelson we saw how relative factor prices are related to goods prices. In particular we saw that wage-rental ratios are inversely related to Computer (K-int) Shoe (L-int) prices: i.e., PC/PS↑=> W/R↓ This relationship is illustrated in the figure below. Wage-rental ratio W/R (W/R)1 (W/R)2 SS (PC/PS)1 (PC/PS)2 PC/PS Before trade relative computer prices are higher in Home country: PC/PS> (PC/PS)W > (PC/PS)* The corresponding W/R is higher in Home country: W/R> (W/R)* 14 International trade leads to equalization of international prices. Convergence of international prices leads to convergence of Home and Foreign factor prices (W/R) (W/R)W (W/R)* SS (PC/PS) (PC/PS)W (PC/PS)* PC/PS Putting it all together: The relationship between goods prices PC/PS , factor prices W/R, and factor content L/K in each sector is illustrated in the figure below. W/R L/KS L/KC (W/R) (W/R)W (W/R)* PC/PS (PC/PS) PC/PS)w (PC/PS)* (Lc/Kc)W (LS/KS)W Once trade opens between the two countries and goods prices equalize, factor prices and factor contents equalize too. L/K 15 The Factor-Price Equalization Theorem: Under HO assumption international trade leads to equalization of factor prices across countries. That is when the prices of the output goods are equalized between countries, as countries move to free trade, then the prices of the factors (capital and labor) will also be equalized between countries. This implies that free trade will equalize the wages of workers and the rentals earned on capital throughout the world. – The theorem derives from the assumptions of the model, the most critical of which is the assumption that the two countries share the same production technology and that markets are perfectly competitive. – In a perfectly competitive market factors are paid on the basis of the value of their marginal productivity which in turn depends upon the output prices of the goods. – Thus, when prices differ between countries so will their marginal productivities and hence so will their wages and rents. – However, once goods prices are equalized, as they are in free trade, the value of marginal products are also equalized between countries and hence the countries must also share the same wage rates and rental rates. Note that the theorem implies that international trade is a substitute for the international mobility of factors Factor-price equalization formed the basis for some arguments often heard in the debates leading up to the approval of the North American Free Trade Agreement (NAFTA) between the US, Canada and Mexico. Opponents of NAFTA feared that free trade with Mexico would lower US wages to the level in Mexico. Factor-price equalization is consistent with this fear although a more likely outcome would be a reduction in US wages coupled with an increase in Mexican wages. Note that if production technologies differ across countries, as we assumed in the Ricardian model, then factor prices would not equalize once goods prices equalize. As such a better interpretation of the factor-price equalization theorem applied to real world settings is that free trade should cause a tendency for factor prices to move together if some of the trade between countries is based on differences in factor endowments. But do Factor Prices Equalize in Reality? Why not? Figure 4.9 shows the estimated labor productivities across countries, and their wages, relative to the United States in 1990. Notice that labor productivity and wages are highly correlated across countries: the points roughly line up along the 45 degree line. This close connection between wages and labor productivity is what we expect from the Ricardian model, and is also what we expect to hold in the Heckscher-Ohlin model once we drop the assumption of identical technologies 16 Summary The Heckscher-Ohlin model, in which two goods are produced using two factors of production, emphasizes the role of resources in trade. A rise in the relative price of the labor-intensive good will shift the distribution of income in favor of labor: • The real wage of labor will rise in terms of both goods, while the real income of capital owners will fall in terms of both goods. The owners of a country’s abundant factors gain from trade, but the owners of scarce factors lose. In reality, complete factor price equalization is not observed because of wide differences in resources, barriers to trade, and international differences in technology. Empirical evidence shows that the Heckscher-Ohlin model is inadequate for trade patterns unless we allow for technological differences. • Differences in resources alone cannot explain the pattern of world trade or world factor prices. 17 Appendix 1 Measuring the Factor Content of Trade How do we measure the pattern of trade when there are thousands of products traded between countries? How can we summarize all that information into categories that allow us to test the Heckscher-Ohlin model? It turns out that Leontief’s test gives us a good way to answer this question. Leontief measured the amount of labor and capital used to produce $1 million worth of U.S. exports and $1 million worth of U.S. imports. If we multiply the numbers shown in Table A.1 by the actual value of U.S. exports, which were $16,700 million in 1947, and U.S. imports, which were $6,200 million, we obtain the values shown in Table 4A.1. These values are called the factor contents of exports and imports, and they measure the amounts of labor and capital used to produce exports and imports. Table 4A.1 Factor Content of Trade for the United States, 1947 In 1947, the net exports of the United States required some $23.4 billion worth of capital and 2 million person-years. The fact that both of these factor contents are positive indicates that the U.S. was running a trade surplus (with the value of exports greater than the value of imports) in that year. Extending the Heckscher-Ohlin Theorem: From the factor contents of net exports in Table 4A.1 we can calculate the capital/labor ratio embodied in net exports, which is $16,700 of capital per person. Given that both capital and labor (as embodied in goods) were being exported, and that the U.S. was capital abundant, we would expect that relatively more capital per person was being exported than that found in the U.S. Was this the case in 1947? In 1947, there was $327 billion of K in the United States, and 47 million L. Taking the ratio K/L= $7,000. $7,000 is the overall average for the U.S. economy, and it is much less that the capital/labor ratio embodied in net exports, of $16,700 from Table 4A.1. So compared with the average for the economy, the U.S. net exports were indeed capital-intensive. 18 Extended Heckscher-Ohlin Theorem If both labor and capital are being exported, and Home is capital abundant, then the capital/labor ratio in net exports should exceed the capital/labor ratio found at Home. The “extended” HO Theorem is more general that our earlier statement of the theorem: this extended version holds even if there are other factors besides labor and capital (like land), being used to produce exports and import-competing goods; it holds with many countries; and it also takes into account the fact that the U.S. had a trade surplus in 1947. So this “extended” version is actually a better way to test the HO model, and we see that it is confirmed for the United States in 1947, and also when it is checked in other years. Many Factors of Production and Testing HO Model It turns out that in a world of many factors of production and many countries the correct test of H-O model is a comparison of a country’s relative factor endowment with its relative income, where the comparison is made with the world total factor endowment and the world total income. The “Sign Test” in the Heckscher-Ohlin Model The sign test states that: If a country is abundant in a factor, then the factor content of net exports should be positive. But if a country is scarce in a factor, then the factor content of net exports should be negative. In order to measure whether a factor is abundant or scarce in a country, we compare the amount of the factor found there with that country’s share of world GDP. So the form of the “sign test” is as follows: Sign of (Country’s % share of factor – % share of world GDP) = Sign of (Country’s factor content of net exports) Let us illustrate this test using the 1947 data for the United States. First let’s do the test for capital: Sign of (US Capital content in net exports) > 0 ($23,400 in Table 4A) Sign of (KUS/KWorld – GDPUS/GDPWorld ) >0 o The U.S. share of world GDP in 1950 was about 40%. o It is hard to estimate the U.S. share of the world capital stock in the post-war years. But given the devastation of the capital stock in Europe and Japan due to World War II, we can presume that the U.S. share of world capital was more than 40%. Have same signs: On capital the United States in 1947 passes the sign test. Now let’s do the test for labor: Sign of (US Labor content in net exports) > 0 ($2 million in Table 4A) Sign of (LUS/LWorld – GDPUS/GDPWorld ) < 0 19 o The U.S. share of world GDP in 1950 was about 40%. o The U.S. share of world population in 1950 was about 6%. Have different signs: On labor the United States in 1947 fails the sign test. So even once we extend the Heckscher-Ohlin model to allow for many goods, factors and countries, the sign test still gives us a paradoxical finding for labor in 1947, similar to Leontief’s original test Differing Productivities Across Countries Now we turn to a second extension, which was actually suggested by Leontief himself when he first discovered the paradox. Leontief said that we should abandon the assumption that technologies are the same across countries, and instead allow for differing productivities, as in the Ricardian model. Let us define the effective amount of a factor in each country as the actual amount found there times its productivity. For example, if Pakistan has a labor force of 100 million people but their productivity is only 5% of that of the United States, then a measure of their effective labor force that would be comparable to the United States would be 5 million people. If we do the same for every other country, and add up the effective labor across all countries we obtain the world effective labor force. A country’s share of effective labor is then its own effective labor force divided by the world’s effective labor force. This idea of an effective factor applies to capital and land, too: we would adjust the amount found in each country by its productivity. The sign test for the extended Heckscher- Ohlin model states that if a country is abundant in the effective amount of a factor, then its factor content of net exports should be positive; but if a country is scarce in the effective amount of a factor, then the factor content of net exports should be negative. This sign test is written as: Sign of (Country’s % share of effective factor – % share of world GDP) = Sign of (Country’s factor content of net exports) The Sign Test in a Recent Year Once Again There are 33 countries and 9 factors in the test. The sign test for the Heckscher-Ohlin model extended to take into account different productivities across countries has been applied to the same 33 countries and nine factors of production we considered earlier (for 1990). We allow capital, seven types of labor, and two types of land to differ in their productivities across countries. 20 The results of the extended sign test are shown in Table 4A.2. For the countries with low GDP per capita (less than one-third of the U.S. level), nearly 6 out of nine effective factors now pass the sign test. This finding suggests that measuring effective factors (rather than actual factor amounts) for the poor and middle-income countries is particularly important. In contrast, for the richest countries the extended sign test performs just the same as it did before, passing for 5.3 factors out of nine, while failing for 3.7 factors. Combining all the countries, the sign test is now successful in more than one-half of the cases (passing for 5.6 factors out of nine, on average). Thus, allowing productivities to differ across countries is an important extension of the Heckscher-Ohlin model that allows the model to better predict actual trade patterns. Table 4A.2 The Sign Test for 33 Countries with Differing Technologies, 1990 Once the FPE is dropped, about three-quarters of cases in the bilateral trade flows have the correct signs i.e., capital abundant countries indeed export more capital intensive goods than they import. Appendix 2 Increasing Wage Inequalities in U.S – is International Trade culpable? Since the early 1980’s the wage of skilled relative to unskilled workers in U.S has increased. Is this related to the growth of exports of manufacturing goods of Newly Industrialized countries, NIC’s? Is this a move toward FPE? There is skepticism based on 4 observations: 1- According to H-O a K-abundant country such as U.S is expected to export Kintensive goods. This would increase r and decrease w. If so then we should observe (r.K/GDP) ↑ and (w.L/GDP)↓. But there has been no change in the distribution of income of K and L. 2- According to SS-Theorem, an increase in the price of skilled intensive good leads to an increase in the wage rate of skilled labor. But there is no clear evidence of a rise in the relative price of skilled intensive goods. 3- If increase in the price of skilled intensive good was the reason for an increase in High skilled-Low skilled wage gap in U.S. then we should have observe the reverse in low-skilled labor abundant countries such as China. That is with an increase in the price of low-skilled intensive goods the wage gap in China should have decreased but in fact the gap has increased in China too. 4- Trade of advanced countries with NIC’s is a small share of total spending in advanced countries. 21 Two explanations for Increasing High skilled-Low skilled Wage Gap in U.S. The skilled-unskilled wage gap has increased dramatically in U.S. But the same pattern in other countries. - The rising wage gap should have led to a shift in employment away from skilled workers, along demand curve, but it has not. - The only explanation consistent with these facts is that there has been an outward shift in the demand for more skilled workers since 1980’s, leading to an increase in their relative employment and wages. - The fact is that the bulk of the increase in the relative demand for skilled labor occurred within the manufacturing industries, and not by shifts in labor between industries. Two explanations are offered to explain this 1 - Outsourcing and trade in intermediate input (offered by Feenstra) - Suppose there are two factors inputs (low skilled labor and skilled labor) used to produce two intermediate goods say Parts and R&D. Parts is a low-skilled intensive product and R&D is a high-skilled-intensive one. The two intermediate goods (Parts and R&D) are bundled together to produce a final good Y (without use of any input). All activities take place within a single manufacturing industry. All three products can be internationally traded. - Suppose Home is a High-skilled abundant country. Then according to H-O model Home would export High-skilled intensive R&D and imports Lowe-skilledintensive Parts. Trade leads to a drop in price of Parts in Home. The effect on wage gap is predicted by Stolper-Samuelson: a reduction in price of Parts leads to an increase in the relative price of High-skilled labor. Notice that absolute wages do not need to fall due to lower final good prices (because of lower input costs). 2 - Non-traded Goods and the Wage Gap (Harrigan) - Harrigan argues that the movement in wages over 1980s and 1990s are not correlated with trade prices or outsourcing, but rather with non-traded goods: i.e. there is a sharp increase in the price of skilled intensive non-traded goods in the U.S. as well as a decrease in the price of unskilled-intensive non-traded goods. - This finding poses a challenge to the idea that either trade or technology is responsible for the changes in wages.