Assessment Introduction

advertisement

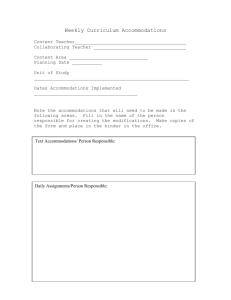

Join Together: A Nationwide On-Line Community of Practice and Professional Development School Dedicated to Instructional Effectiveness and Academic Excellence within Deaf/Hard of Hearing Education Objective 2.4 – Assessment Submitted by: Topical Team Leaders – John Luckner, Ed.D. and Sandy Bowen, Ph.D. 1 Topic – Test Adaptations Rationale Legislated mandates ensure the participation of students with disabilities in current education reform efforts. The provision of assessment accommodations within current legislation is used to ensure that students with disabilities participate in assessments on a ‘level playing field’ with their non-disabled peers (McDonnell et al., 1997; Pitoniak & Royer, 2001; Schulte et al., 2000; Thurlow & Bolt, 2001; Thurlow et al., 2000). With the use of accommodations, students who are D/HH who otherwise would not be able to participate in statewide assessments, or who would participate but not on a ‘level playing field’, can now participate demonstrating their knowledge and/or skills on standardized tests without being penalized for aspects related to their disabilities that might interfere with their ability to demonstrate their knowledge or skills. Federal Legislation and State Policies Federal legislation within the United States has played a critical role in the education of children with disabilities. Four major pieces of legislation within the United States have been passed that effect persons with disabilities and their access to nondiscriminatory testing on the basis of their disability. Stemming from each of these federal laws, are individual state’s policies with respect to testing accommodations for students with disabilities. Rehabilitation Act of 1973, Section 504 (P. L. 93-112). The Rehabilitation Act of 1973 was the first major piece of legislation related to persons with disabilities (Phillips, 1994). Section 504 requires that accommodations be made in any program or activity receiving federal funding or assistance so that persons with disabilities are given equal access and participation. This includes that adaptations are required for those individuals with physical or mental disabilities, or for those having a record of such disabilities, or for those regarded as having such disabilities (Rehabilitation Act, Section 504, 1973). The Americans with Disabilities Act (PL 101-336). The Americans with Disabilities Act extended the protections afforded persons with disabilities within the Rehabilitation Act of 1973 to the private sector. The Individuals with Disabilities Education Act (IDEA: PL 101-476) and IDEA Amendments of 1997 (IDEA 97: PL 105-17). The 1997 reauthorization of the IDEA requires that students with disabilities be included in statewide and district-wide assessments, with appropriate accommodations where necessary (PL 105-17). Participation in state and district-wide assessments is viewed as a related component. No Child Left Behind, Title I Provisions (PL 107-110). The Title I provisions within the No Child Left Behind (NCLB) legislation of 2001 provide that students with disabilities participate in state assessments and accountability reporting (PL 107-110). As such, NCLB requires, like IDEA 97, students with disabilities be afforded the accommodations necessary for their participation in such assessments. 2 State Policies. State policies shape the use of accommodations in large-scale assessment, though they do not delineate the actual usage of accommodations by students with disabilities (Koretz & Barton, 2003; Sireci et al., 2000; Thurlow, House, Boys, Scott, and Ysseldyke, 2000). As such, states have varying policies with respect to accommodations, impacting both district and statewide assessments. General Accommodations Guidelines: Hearing Students For hearing students who do not have disabilities, no general guidelines exist with respect to testing accommodations, as none are needed. For hearing students with disabilities (other than hearing impairment), a variety of testing accommodations and policies have been established. Test Accommodations: Definitions and Types Accommodations have been defined within the literature as changes in the assessment materials or procedures that address the aspects of a student’s disability that may interfere with their ability to demonstrate knowledge and/or skills on standardized tests (Thompson, Blount, & Thurlow, 2002; Thurlow & Bolt, 2001; Tindal & Fuchs, 1999). Accommodations are a means of attempting to make the assessment (testing) process more equitable for persons with disabilities by eliminating barriers to meaningful testing based upon disability (Thurlow & Bolt, 2001; Tindal & Fuchs, 1999). The goal is to ‘level the playing field’ among students with and without disabilities, while at the same time ensuring that administering the test under non-standard conditions does not alter the validity of the test (McDonnell et al., 1997; Pitoniak & Royer, 2001; Schulte et al., 2000; Thurlow & Bolt, 2001; Thurlow et al., 2000) Within the literature and practice, four major categories, or types, of accommodations have been utilized by students with disabilities. These include accommodations related to: 1) timing and/or scheduling, 2) presentation of testing materials, 3) response to testing materials, and 4) setting: environment or administration of assessments (Thompson et al., 2002; Thurlow et al., 1998). Timing/Scheduling. Timing and scheduling accommodations are those that address the total amount of time a student is allotted to complete the assessment, the time of day during which the assessment occurs, or the length of the testing session. These accommodations could include: extended time, multiple day testing, frequent breaks within testing sessions, or the provision of breaks between testing sessions. Presentation. Presentation accommodations are those that are made that affect the appearance of testing materials, or administration of the assessment. Some examples include: oral presentation, large print edition of the test, Braille, sign language administration, oral administration (“read aloud”), computer administration, and simplified language. 3 Response. Response accommodations are those that are made that enable the student with disabilities to respond or indicate his or her answers to the test materials via methods different from standard means. Examples include: dictated (use of a scribe), signed, or tape recorded responses, use of Braille, use of a word processor, use of a calculator, and marking answers directly in the test booklet. Setting. Setting accommodations are those that are made to the setting in which the assessment is administered to the student. Examples of these could include: individualized testing in a place free from distractions (separate setting), small group administration, preferential seating within the testing room, and use of a study carrel. In addition to the four categories, or types, of accommodations described above, use of multiple accommodations during testing often occurs. These are sometimes referred to as ‘accommodations packages’ (Thompson et al., 2002; Thurlow et al., 1998). Formal Assessment Accommodations Best Practices: Hearing Students No formal assessment accommodations best practices exist for hearing students without disabilities. For hearing students with disabilities (other than hearing impairment), a variety of testing accommodations and policies have been established. Thompson, Blount, and Thurlow (2002) analyzed 46 empirical research studies published between 1999 and 2001 that examined the use of testing accommodations by students with disabilities during large-scale testing. Thompson et al. (2002) found the primary purpose of accommodations research conducted between 1999 and 2001 to be to determine the effect of accommodations on large-scale test scores (performance) of students with disabilities. The second most common purpose was to investigate the effects of accommodations on test validity. The results of the 46 studies analyzed and reviewed were presented according to each type of accommodation utilized within the research. Major categories included read aloud, computer administration, extended time and multiple days, and meta-analyses. Thompson et al. (2002) found that the accommodations of computer administration, oral presentation, and extended time demonstrated a positive effect on student performance (test scores) on at least four studies within their review. Additionally, Thompson et al. (2002) found that other studies within their review examining these same accommodations found no significant impact on students with disabilities test scores. As such, they concluded that additional studies were necessary in order to investigate the effects of specific accommodations on student performance under more stringently delineated conditions (Thompson et al., 2002). Thurlow and Bolt (2001) compiled data from the National Center on Educational Outcomes (NCEO) searchable database on research in accommodations. Their report addressed the accommodations most frequently allowed within state policies regarding large-scale testing, summarizing information available at the time with respect to the most frequently allowed testing accommodations. Thurlow and Bolt (2001) noted that the accommodations they discussed within their report were not necessarily the most frequent utilized, rather the most frequently permitted within state policies. 4 Informal Assessment Accommodations Best Practices: Hearing Students No informal assessment accommodations best practices exist for hearing students without disabilities. For hearing students with disabilities other than hearing impairment, students may use accommodations per federal legislation and state policies during district and statewide testing, as well when accessing their educational program for daily assignments and testing as provided within the student’s Individualized Education Plan (IEP) or 504 Plan. Some basic accommodations have been reviewed. These are presented here. Read Aloud Results related to the presentation read aloud accommodation include that this accommodation was generally found to have positive effects on performance (test scores) of students with disabilities. However, two studies reported that the read aloud accommodation affected the construct the test was intended to measure (Thompson et al., 2002). Some within the fields of education and measurement believe that use of the read aloud accommodation on tests designed to measure reading changes the construct of what is being measured from reading proficiency to listening comprehension (Meloy, Deville, & Frisbie, 2000; Phillips, 1994). Others such as Elliott, Ysseldyke, Thurlow, & Erickson (1998) and Harker & Feldt (1993), maintain that the read aloud accommodation levels the playing field for students who have reading disabilities due to their disability. Much of the debate and controversy surrounding the read aloud accommodation is related to the aspect of test constructs being changed and test score validity due to the use of the accommodation (Koretz & Barton, 2003; McKevitt & Elliott, 2003; Meloy et al., 1998; Phillips, 1994). Most studies addressing the read aloud accommodation have been examined student performance on mathematics achievement tests. While some studies have been conducted that address the read aloud accommodation on tests of reading achievement, these are considered more controversial due to the potential that the construct being measured will be altered (Koretz & Barton, 2003; McKevitt & Elliott, 2003; Meloy et al., 1998; Phillips, 1994). Some of these studies found that students with disabilities performed better (obtained higher scores) when the read aloud accommodation was utilized, permitting tests to be read to them (Koretz, 1997; Meloy et al., 2000; Tindal et al., 1998). Harker and Feldt (1993) found that students without disabilities who were considered poor readers performed better under accommodated conditions, but those students considered strong readers were adversely affected by use of the accommodation. Bielinski, Thurlow, Ysseldyke, Freidebach, and Freidebach (2001) conducted a study to investigate the effect that the read aloud accommodation had on the validity of math test scores and reading comprehension test scores of students with identified disabilities and established Individualized Education Plans (IEPs) in the area of reading and with nondisabled students. Bielinski et al. (2001) sought answers to two questions related to item difficulty for students with disabilities and those without, in accommodated and non-accommodated conditions. Results indicated that for students with reading disabilities taking a 3rd grade test of reading comprehension, and a 4th grade mathematics achievement test, the use of the read aloud accommodation was either unnecessary, or the accommodation only benefited 5 a subgroup of the student population (Bielinski et al., 2001). Additionally, the authors state that it would appear that the reading comprehension test utilized measures the reading construct differently for students with an identified reading disability and those without, regardless of having received or not received the read aloud accommodation (Bielinski et al., 2001). The authors raised the question of how to determine those students who would benefit from a particular accommodation (Bielinski et al., 2001). Additionally, Bielinski et al. (2001) conclude that 1) more research is needed to determine best practice for measuring reading proficiency for students with identified reading difficulties or disabilities, and 2) “strong conclusions about the validity of the read-aloud accommodation itself will require the accumulation of evidence from many studies, including more analysis of extant data” (Bielinski et al., 2001: 17). Meloy, Deville, & Frisbie (2000) studied the effects of a read aloud accommodation on the test performance of 198 middle school students with identified learning disabilities in reading and 68 middle school students without identified disabilities. Students were randomly assigned to either the ‘read aloud’ or ‘standard’ test administration conditions for taking the Math Problem-Solving and data Interpretation, Reading Comprehension, and Science, Usage and Expression tests within the Iowa Test of Basic Skills (ITBS) (Meloy et al., 2000). Results indicated that use of a read aloud testing accommodation by students with learning disabilities in the area of reading significantly positively impacted their performance, with these students obtaining higher scores than their peers with reading learning disabilities who took the tests under standard (non-accommodated) conditions (Meloy et al., 2000). Additionally, results indicated that the students without disabilities also scored significantly higher that their nondisabled peers tested using standard administration conditions (Meloy et al., 2000). As such, Meloy et al. (2000) concluded that general use of the read aloud accommodation for students with learning disabilities taking standardized achievement tests would not be recommended. McKevitt and Elliott (2003) conducted a study examining and analyzing the accommodations teachers believed valid and appropriate for students, as well as the effect teacher recommended accommodations and reading accommodations packages had on the performance of students with and without disabilities. Results indicated that use of the reading accommodations packages were not consistently or necessarily effective for students with disabilities or their nondisabled peers. Computer Administration Research conducted to determine the effects of computerized administration of assessments as an accommodation for students with disabilities yielded varied results. The majority of the nine studies revealed computer administered assessment had a positive effect on student performance (Thompson et al., 2002). Other results included no significant effects on scores were obtained under the accommodated condition, while other studies found the use of computerized administration affected the construct of the assessments (Thompson et al., 2002). Calhoon, Fuchs, and Hamlett (2000) compared the effects of several testing accommodations utilized by secondary aged students with learning disabilities on performance when taking mathematics assessments. The accommodations were all 6 presentation accommodations, and included “read aloud”, and computerized administration, both with and without supplemental video (Calhoon et al., 2000). Student performance with accommodations was compared to performance utilizing standard paper and pencil administration of the assessment (Calhoon et al., 2000). Results indicated that each accommodation had a positive effect on student performance. Students with learning disabilities with varying reading abilities all benefited significantly from the accommodations (Calhoon et al., 2000). Extended Time and Multiple Day Extended time is one of the most widely studied and frequently utilized testing accommodations for students with disabilities. Walz, Albus, Thompson, and Thurlow (2000) examined the effects of using a multiple-day test accommodation on the performance of middle school students with learning disabilities. Results indicated that use of a multiple-day testing accommodation did not (significantly) enhance the performance scores of the students (Walz et al., 2000). Additionally, results indicated that general education students’ test scores were significantly negatively affected when taking the test across multiple days (Walz et al., 2000). Zurcher and Bryant (2001) conducted an examination of the effects of extended time accommodations on the performance of 15 college students with identified learning disabilities and 15 college students without disabilities on the Miller Analogies Test (MAT). Two of the student specific accommodations were accommodations packages, including accommodations (oral and oral with scribe) in addition to extended time (Zurcher & Bryant, 2001). Results of the Zurcher and Bryant (2001) investigation indicated no significant improvement for students with or without disabilities under the accommodated testing condition. It should be noted that several limitations to their study were present, including small sample size; students were not randomly selected, nor were students matched. Runyon (1991) examined the effect of extended time on student performance (scores) for college students with learning disabilities, and those without. Results indicated that the extended time accommodation positively effected students with learning disabilities mean percentile reading scores. The use of extended time by students without learning disabilities had no significant effect. General Accommodations Guidelines: Students who are Deaf or Hard of Hearing Students who are D/HH are permitted the use of accommodations during instruction and testing as per federal legislation. Within the current literature base, there is no documentation regarding what is considered to be best practice for students who are deaf or hard of hearing with respect to accommodations usage. That is, though a variety of accommodations have been, and are, utilized by students who are deaf or hard of hearing, not all have been shown to be effective, or to have made statistically significant differences with respect to assessment outcomes. Students who are D/HH often require presentation accommodations, such as use of a sign language interpreter, during assessment. Students who are D/HH who have additional disabilities may use multiple accommodations, or ‘accommodations packages’ during assessment. The prevalence of specific disability categories varies greatly and is inconsistent from state to state (Table 1). The incidence of hearing impairment is low; 7 and, as such, one would expect to see this reflected within the accommodations literature either with small amounts of reference to students identified as D/HH, or through little disaggregated data specific to disability category and accommodations types utilized. Formal Assessment Accommodations Best Practices: Students who are Deaf or Hard of Hearing No formal assessment accommodations best practices exist for students who are deaf or hard of hearing. However, several large testing boards have provided accommodation guidelines. The ACT Testing Services, the College Board, and the Educational Testing Service (ETS) offer accommodations to students with disabilities taking examinations Students who are D/HH are eligible to utilize a sign language interpreter or an oral interpreter to translate testing directions. The College Board states that use of a sign language interpreter or an oral interpreter may be used for examinees who are D/HH “to translate testing directions from spoken English into American Sign Language or an English-based sign system” (http://www.collegeboard.com/disable/students/html/accom.html). The College Board states that if the only accommodation needed by the examinee is use of an interpreter, the examinee may test at a national administration, and that the test would be considered a “standard administration”. All examinees requiring use of an interpreter are responsible for providing their own interpreter. The College Board does not require a student eligibility form for use of an interpreter to translate spoken testing directions during testing administration. Students who are D/HH are required to inform the College Board Service for Students with Disabilities division in writing that they will be utilizing an interpreter. The ACT Testing Services, like the College Board, permits the use of interpreters during testing administration for students who are D/HH. The ACT cites the following as examples of standard- time national testing accommodations students with hearing impairments may request: “seating near the front of the room to lip-read spoken instructions; a sign-language interpreter (not a relative) to sign spoken instructions (not the test items); a printed copy of spoken instructions with visual notification from testing staff of test start, time remaining, and stop times” (http://www.act.org/aap/disab/opt1.html). Students who are D/HH using above described accommodations would have their tests considered as “standard-time” administrations, and their test scores would be reported as “National”. The ETS website states, “reasonable testing accommodations are provided to allow candidates with documented disabilities (recognized under the Americans with Disabilities Act) an opportunity to demonstrate their skills and knowledge” (www.ets.org/disability/info.html). The ETS states that use of a sign language interpreter for spoken directions only may be used for examinees who are D/HH. Additionally, the ETS notes that examinees may test under standard conditions should they (ETS) determine the accommodation requires only minor modifications to the testing environment. As an example, the ETS cites the use of a sign language interpreter for directions. 8 Informal Assessment Accommodations Best Practices: Students who are Deaf or Hard of Hearing No informal assessment accommodations best practices exist for students who are deaf or hard of hearing. However, several guidelines have been presented. In addition to their use during district and statewide testing, accommodations may be provided during testing done within students’ school classes as provided within the student’s Individualized Education Plan (IEP) or 504 Plan. The IDEA requires that access to testing accommodations be available to students throughout daily instruction in order for them to access the general curriculum (IDEA 97, PL 105-17). As such, it is important that teachers of students who are D/HH, know about the specific accommodations each of their students requires, and is legally entitled to utilize, not only during standardized and informal testing situations, but during the course of daily instruction. Additionally, teachers must know how to provide access to, and implement use of, these accommodations for their students who are D/HH. Summary of Accommodations Research The literature that exists within the fields of accountability and the provision of testing accommodations shows a variety of accommodations types, and findings with respect to a broad spectrum of students identified as having disabilities. Some research presented within this context includes that which addressed accommodations within the categories of 1) timing and/or scheduling, 2) presentation of testing materials, 3) response to testing materials, and 4) setting: environment or administration of assessments. Gleaning accommodations data for students identified as D/HH from the body of accommodations research is difficult to do. This is because the preponderance of the existing body of research does not disaggregate data by type of accommodation. Additionally, data for students with low incidence disabilities, such as sensory loss including hearing impairment, most often is not disaggregated. Accommodations research is complex. As shown within this review and others, it often demonstrates inconsistent results across different studies of similar assessment accommodations. Though no indisputable effects were found for particular accommodations across the literature, it is important to remember that the provision of testing accommodations during testing provides students with disabilities access to the material, and promotes equity and validity within educational assessment. As such, it is an area that requires further attention and research to increase our body of knowledge and promote more accessible, equitable, and valid educational assessment of students. References ACT Assessment Services for Students with Disabilities: Testing Accommodations for Students with Disabilities 2004-2005. Retrieved 6-29-04 from the World Wide Web: http://www.act.org/aap/disab/chart.html The Americans with Disabilities Act (PL 101-336). 9 Bielinski, J., Thurlow, M., Ysseldyke, J., Freidebach, J., & Freidebach, M. (2001). Readaloud accommodations: Effects on multiple-choice reading and math items. Technical Report 31. Minneapolis, MN: University of Minnesota, National Center on Educational Outcomes (NCEO). Retrieved 10-24-2003 from the World Wide Web: http://education.umn.edu/nceo/OnlinePubs/Technical31.htm Calhoon, M. B., Fuchs, L. S., & Hamlett, C. L. (2000). Effects of computer-based test accommodations on mathematics performance assessments for secondary students with learning disabilities. Learning Disabilities Quarterly, 23, 4, 271-282. College Board: Services for Students with Disabilities: Accommodations. Retrieved 629-04 from the World Wide Web: http://www.collegeboard.com/disable/students/html/accom.html The Educational Testing Service: Disabilities and Testing. Retrieved 6-29-04 from the World Wide Web: http://www.ets.org/disability/index.html The Education of All Handicapped Children Act of 1975 (P.L. 94-142) Elliott, Ysseldyke, Thurlow, & Erickson (1998). What about assessment and accountability? Practical implications for educators. Teaching Exceptional Children, 31, 1, 20-27. Fuchs, L. S. & Fuchs, D. (2001). Helping teachers formulate sound test accommodation decisions for students with learning disabilities. Learning Disabilities Research & Practices, 16, 3, 174-181. Gordon, R. P., Stump, K., & Glaser, B. A. (1996). Assessment of individuals with hearing impairments: Equity in testing procedures and accommodations. Measurement and Evaluation in Counseling and Development, 29, 111-119. The Individuals with Disabilities Education Act (IDEA: PL 101-476) The Individuals with Disabilities Education Act Amendments of 1997, 20 U.S.C. (IDEA 97: PL 105-17) Haigh, J. (1999). Accommodations, modifications, and alternates for instruction and assessment (Maryland/Kentucky Report 5). Minneapolis, MN: University of Minnesota, National Center on Educational Outcomes. Retrieved 10-16-2003 from the World Wide Web: http://education.umn.edu/NCEO/OnlinePubs/MdKy5. Harker, J. K. & Feldt, L. S. (1993). A comparison of achievement test performance of non-disabled students under silent reading and reading plus listening modes of administration. Applied Measurement in Education, 6, 307-320. McDonnell, L. M. McLaughlin, M. J., & Morrison, P. (Eds.) (1997). Educating one and all: Students with disabilities and standards-based reform. Washington, D. C.: National Academy Press. 10 McKevitt, B. C., & Elliott, S. N. (2003). Effects and perceived consequences of using read-aloud and teacher-recommended testing accommodations on a reading achievement test. School Psychology Review, 32, 4, 583-600. Meloy, Deville, & Frisbie (April, 2000). The effects of a reading accommodation on standardized test scores of learning disabled and non learning disabled students. A paper presented for the National Council on Measurement in Education Annual Meeting. New Orleans, LA No Child Left Behind Act of 2001 (PL 107-110), 2001 Phillips, S. E. (1994). High-stakes testing accommodations: Validity versus disabled rights. Applied Measurement in Education, 7, 93-120. Pitoniak, M. & Royer, J. (2000). Testing accommodations for examinees with disabilities: A review of psychometric, legal, and social policy issues. Review of Educational Research, 71, 1, 53-104. Ray, S. R. (1989). Adapting the WISC-R for deaf children. Diagnostique, 7, 147-157. Ray, S. R. (1989). Context and the psychoeducational assessment of hearing impaired children. Topics in language Disorders, 9, 4, 33-43. Rehabilitation Act of 1973, Section 504 (P.L. 93-112). Runyon, M. K. (1991). The effect of extra time on reading comprehension scores for university students with and without learning disabilities. Journal of Learning Disabilities, 24, 2, 104-108. Schulte, A. G., Elliot, S. N., & Kratochwill, T. R. (2001). Effects of testing accommodations on students’ standardized mathematics test scores: An experimental analysis. School Psychology Review, 30, 527-547. Sireci, S. G., Li, S., & Scarpati, S. (200). Center for Educational Assessment Research Report no. 485 (PDF file) School of Education, University of Massachusetts Amherst. This paper was commissioned by the Board on Testing and Assessment of the National Research Council of the National Academy of Sciences. Retrieved 6-1-2004 from the World Wide Web: http://education.umn.edu/nceo/new.htm Sullivan, P. M. (1982). Administration modifications on the SIXC-R performance scale with different categories of deaf children. American Annals of the Deaf, 127, 6, 780-788. Thompson, Blount, & Thurlow (2002). A summary of research on the effects of test accommodation 1999 through 2001. Technical Report 34. Minneapolis, MN: University of Minnesota, National Center on Educational Outcomes (NCEO). 11 Retrieved 9-28-2003 from the World Wide Web: http://education.umn.edu/NCEO/OnlinePubs/Technical34.htm Thompson, S. J., Erickson, R., Thurlow, M. L., Ysseldyke, J. E., Callender, S. (1999). Status of the states in the development of alternate assessments (Synthesis Report No. 31). Minneapolis, MN: University of Minnesota, National Center on Educational Outcomes. Retrieved 9-28-2003, from the World Wide Web: http://education.umn.edu/NCEO/OnlinePubs/Synthesis31.html Thurlow, M., & Bolt, S. (2001). Empirical support for accommodations most often allowed in state policy (Synthesis Report 41).Minneapolis, MN: University of Minnesota, National Center on Educational Outcomes. Retrieved [today's date], from the World Wide Web: http://education.umn.edu/NCEO/OnlinePubs/Synthesis41.html Thurlow M. E., Elliott, J. L., & Ysseldyke, J. E. (1998). Testing students with disabilities: Practical strategies for complying with district and state requirements. Thousand Oaks, CA: Corwin Press, Inc. Thurlow, M., House, A., Boys, C., Scott, D., & Ysseldyke, J. (2000). State participation and accommodation policies for students with disabilities: 1999 update (Synthesis Report No. 33). Minneapolis, MN: University of Minnesota, National Center on Educational Outcomes. Retrieved 11-15-2003, from the World Wide Web: http://education.umn.edu/NCEO/OnlinePubs/Synthesis33.html Thurlow, M., & Wiener, D. (2000). Non-approved accommodations: Recommendations for use and reporting (Policy Directions No. 11). Minneapolis, MN: University of Minnesota, National Center on Educational Outcomes. Retrieved 10-4-2003, from the World Wide Web: http://education.umn.edu/NCEO/OnlinePubs/Policy11.htm Thurlow, M., Ysseldyke, J., Bielinski, J., House, A., Trimble, S., Insko, B., Owens, C. (2000). Instructional and assessment accommodations in Kentucky (MarylandKentucky Report 7). Minneapolis, MN: University of Minnesota, National Center on Educational Outcomes. Retrieved [06-14-04], from the World Wide Web: http://education.umn.edu/NCEO/OnlinePubs/MDKY_7. Thurlow, M. L., Ysseldyke, J. E., & Silverstein, B. (1995). Testing accommodations for students with disabilities. Remedial and Special Education, 16, 5, 260-270. Tindal, G & Fuchs, L. (1999). Summary of research on test changes: An empirical basis for defining accommodations. Lexington, KY: University of Kentucky Mid-south Regional Resource Center, Interdisciplinary Human Development Institute. Tindal, G., Heath, B., Hollenbeck, K., Almond, P., & Harniss, M. (1998). Accommodating students with disabilities on large-scale tests: An experimental study. Exceptional Children, 64, 4, 439-450. 12 U.S. Department of Education, (2001). To assure the free appropriate public education of all children with disabilities: 23rd Annual report to Congress on the implementation of the Individuals with Disabilities Education Act. Table AA10. Retrieved 10-4-2003 from the World Wide Web: http://www.ed.gov/about/reports/annual/osep/2001/appendix-a-pt1.doc Walz, Albus, Thompson, & Thurlow (2000). Effect of a multiple day test accommodation on the performance of special education students. Minneapolis, MN: University of Minnesota, National Center on Educational Outcomes (NCEO). Retrieved 9-282003 from the World Wide Web: http://education.umn.edu/nceo/OnlinePubs/MnReport34.html Ysseldyke, J, & Thurlow, M.(1994). Guidelines for inclusion of students with disabilities in large-scale assessments (Policy Directions No. 1). Minneapolis, MN: University of Minnesota, National Center on Educational Outcomes. Retrieved 628-04, from the World Wide Web: http://education.umn.edu/NCEO/OnlinePubs/Policy1.html Zurcher and Bryant (2001). The validity and comparability of entrance examination scores after accommodations are made for students with LD. Journal of Learning Disabilities, 34, 5, 462-471. 13 Table 1 Percentage of Students Ages 6-17 years Served Under IDEA, Part B, States and U.S. (50 States and the District of Columbia), 1999-2000 Lowest State All Disabilities 9.11 (CO) Specific Learning Disabilities Highest State 15.58 (RI) 3.04 (KY) U.S. Total 11.26 9.05 (RI) 5.68 Speech or Language Impairments 1.01 (IA) 3.86 (WV) 2.27 Mental Retardation 0.32 (NJ) 2.97 (WV) 1.13 Emotional Disturbance 0.10 (AR) 1.92 (VT) 0.93 Hearing Impairments 0.04 (DC) 0.20 (UT) 0.14 Orthopedic Impairments 0.04 (NJ; UT) 0.68 (DE) 0.14 Visual Impairments 0.02 (IA; NJ) 0.55 (DC) 0.05 Note: From U.S. Department of Education, To assure the free appropriate public education of all children with disabilities: 23 rd Annual report to Congress on the implementation of the Individuals With Disabilities Education Act. 2001, Table AA10. Available online at http://www.ed.gov/about/reports/annual/osep/2001/ appendix-a-pt1.doc 14 Table 2 Percentage of Kentucky Students With Disabilities Receiving Assessment Accommodations, by Grade, 1995 Grade 4 Grade 8 Grade 11 None 19 33 39 Oral presentation 72 56 45 Paraphrasing 49 48 47 Dictation 50 14 5 Cueing 10 12 10 Technological aid 3 5 5 Interpreter 2 3 4 Other 8 5 6 Note: Individual students may receive multiple accommodations. From Koretz, D. (1997). Assessment of students with disabilities in Kentucky (CSE Tech. Rep. No. 431), University of California, Los Angeles, Center for Research on Evaluation, Standards, and Student Testing, p. 13 (Table 6). 15