Government of India v

advertisement

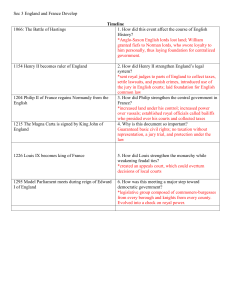

Government of India v Taylor [1955] AC 491 House of Lords A claim by a foreign state for unpaid tax is unenforceable in Australia. [In 1947 an English company, Delhi Electric Supply and Traction Co Ltd, which had carried on business in India for many years, sold its business in that country and remitted the sale proceeds to England. In 1949 the company went into voluntary liquidation in England and the respondents, Samuel Taylor and William Hume, were appointed liquidators of the company. In the course of the liquidation a claim was made by the appellant, the Government of India (India being then a sovereign independent republic), in respect of unpaid income or “capital gains” tax owed by the company under Indian law. The claim was rejected by the respondents on the ground that “no part of the company’s assets (all of which were then in England) could properly be applied in payment of any claim for taxes by a foreign government” (per Viscount Simonds at p 493). Vaisey J, in the English High Court, refused an application by the appellant for an order reversing the rejection of its claim. The English Court of Appeal agreed with Vaisey J.] VISCOUNT SIMONDS. … [503] My Lords, I will admit that I was greatly surprised to hear it suggested that the courts of this country would and should entertain a suit by a foreign State to recover a tax. For at any time since I have had any acquaintance with the law I should have said as Rowlatt J said in the King of the Hellenes v Brostron (1923) 16 Ll L Rep 190, 193: It is perfectly elementary that a foreign government cannot come here – nor will the courts of other countries allow our Government to go there – and sue a person found in that jurisdiction for taxes levied and which he is declared to be liable to in the country to which he belongs. That was in 1923. In 1928 Tomlin J in In re Visser, Queen of Holland v Drukker [1928] Ch 877, 884 after referring to the case of Sydney Municipal Council v Bull [1909] 1 KB 7 in which the same proposition had been [504] unequivocally stated by Grantham J, and saying that he was bound to follow it, added: My own opinion is that there is a well-recognized rule, which has been enforced for at least 200 years or thereabouts, under which these courts will not collect the taxes of foreign States for the benefit of the sovereigns of those foreign States; and this is one of those actions which these courts will not entertain. … My Lords, the history and origin of the rule, if it be a rule, are not easy to ascertain and there is on the whole remarkably little authority upon the subject. … [Viscount Simonds referred to “the age of Lord Mansfield CJ”.] That great judge in a series of cases repeated the formula “For no country ever takes notice of the revenue laws of another.” See Planché v Fletcher (1779) 1 Doug 251, 253, Holman v Johnson (1775) 1 Cowp 341, 343 and Lever v Fletcher (1780) unrep … [505] Where Lord Mansfield led, Lord Kenyon CJ followed, though he was not a judge who followed blindly. I agree with the learned Master of the Rolls [Evershed MR in the present case] [1954] RA/IntLaw07/Govt India v Taylor 2 Ch 131, 147-9 that it is clear from such cases as Clugas v Penaluna (1791) 4 Term Rep 466, Bernard v Reed (1794) 1 Esp 91 and Waymell v Reed (1794) 5 Term Rep 599 that Lord Kenyon accepted without qualification the broad rule which Lord Mansfield had formulated. … Here, my Lords, is a formidable array of authority. It is possible that the words “take notice of” might, if applied without discrimination, lead to too wide an application of the rule; for as Lord Tomlin pointed out in In re Visser [1928] Ch 877, 883 there may be cases in which our courts, although they do not enforce foreign revenue law, are bound to recognise some of the consequences of that law, and for this reason the terms of Lord Mansfield’s proposition have been criticized. But in its narrower interpretation it has not been challenged except in the three cases mentioned earlier in this opinion and in them it was unequivocally affirmed. … [509] I would dismiss this appeal with costs. LORD KEITH of AVONHOLM. … I am in full concurrence with the opinion of my [510] noble and learned friend Viscount Simonds. Such additional observations as I make … are due to the fact that I have had access to a judgment delivered by Kingsmill Moore J in the High Court of Eire on July 21, 1950, in the case of Peter Buchanan Ltd v McVey. This admirable judgment, which somehow has escaped the notice of the reporters, covers all the points raised … [in this] appeal and was affirmed by the Irish Court of Appeal on December 19, 1951. It illustrates two propositions: (1) that there are circumstances in which the courts will have regard to the revenue laws of another country; and (2) that in no circumstances will the courts directly or indirectly enforce the revenue laws of another country. … The plaintiff company was a company registered in Scotland which had been put into liquidation by the revenue authorities in Scotland under a compulsory winding-up order in respect of a very large claim for excess profits tax and income tax. The liquidator was really a nominee of the revenue. The defendant held 99 one pound shares of the capital of the company and the remaining share was held by a confidential cashier and bookkeeper as trustee for him. These two sole shareholders were also sole directors. The defendant having realized the whole assets of the company in his capacity as a director and having satisfied substantially the whole of the company’s indebtedness, other than that due to the revenue, by a variety of devices had the balance transferred to himself to his credit with an Irish bank and decamped to Ireland. The action was in form an action to recover this balance from the defendant at the instance of the company directed by the liquidator. … The judge held that the transaction was a dishonest transaction designed to defeat the claim of the revenue in Scotland as a creditor … . On the other hand, he held that although the action was in form an action by the company to recover these assets it was in substance an attempt to enforce indirectly a claim to tax by the revenue authorities of another State. He accordingly [511] dismissed the action. … One explanation of the rule thus illustrated may be thought to be that enforcement of a claim for taxes is but an extension of the sovereign power which imposed the taxes, and that an assertion of sovereign authority by one State within the territory of another … is (treaty or convention apart) contrary to all concepts of independent sovereignties. … RA/IntLaw07/Govt India v Taylor 3 [513] I agree the appeal should be dismissed. LORD SOMERVELL of HARROW. …[514] If one State could collect its taxes through the courts of another, it would have arisen through what is described, vaguely perhaps, as comity or the general practice of nations inter se. The appellant was therefore in a difficulty from the outset in that after considerable research no case of any country could be found in which taxes due to State A had been enforced in the courts of State B. … Tax gathering is an administrative act, though in settling the quantum as well as in the final act of collection judicial process may be involved. Our courts will apply foreign law if it is the proper law of a contract, the subject of a suit. Tax gathering is not a matter of contract but of authority and administration as between the State and those within its jurisdiction. … [I]t would be remarkable comity if State B allowed the time of its courts to be expended in assisting in this regard the tax gatherers of State A. … [515] That fact, I think, itself justifies what has been clearly the practice of States. They have not in the past thought it appropriate to seek to use legal process abroad against debtor taxpayers. They assumed, rightly, that the courts would object to being so used. … [Lord Morton of Henryton and Lord Reid agreed with Viscount Simonds.] Appeal dismissed Notes 1. For a contemporary example of the operation of the foreign revenue law exclusionary doctrine: see Jamieson v Commissioner for Internal Revenue [2007] NSWSC 324 (Gzell J). Background An Australian citizen domiciled in New South Wales, Robert Hastings, died in the United States in 2004. After his death, the United States Commissioner for Internal Revenue obtained judgment in the United States Tax Court for $US1.149m against Mr Hastings’ deceased estate in respect of unpaid United States income tax. In proceedings in New South Wales, the executor of Mr Hastings’ deceased estate, his daughter, Michelle Jamieson, sought a determination that she was not required to admit the United States Commissioner for Internal Revenue as a creditor of the estate. Disposition Applying Government of India v Taylor [1955] AC 491, Ms Jamieson was entitled to the relief which she sought. 2. The foreign revenue law exclusionary doctrine generally precludes the enforcement of a foreign revenue judgment (such as the judgment of the United States Tax Court in Jamieson) as well as a foreign revenue debt (as in Government of India v Taylor). However, there are two exceptions. The Foreign Judgments Act 1991 (Com) makes provision for the enforcement in Australia of Papua New Guinea income tax judgments and New Zealand tax judgments generally: see s 3(1) (definition of “enforceable money judgment”). RA/IntLaw07/Govt India v Taylor 4 3. A treaty between Australia and a foreign state may provide for assistance in the recovery in Australia of foreign revenue claims: see the Conventions dated 20 June 2006 between Australia and France and 8 August 2006 between Australia and Norway for the avoidance of double taxation and the prevention of fiscal evasion. Article 26 of the 2006 Convention between Australia and France and Article 27 of the 2006 Convention between Australia and Norway are as follows: 1. The Contracting States shall lend assistance to each other in the collection of revenue claims. … 3. When a revenue claim of a Contracting State is enforceable under the laws of that State and is owed by a person who, at that time, cannot, under the laws of that State, prevent its collection, that revenue claim shall, at the request of the competent authority of that State, be accepted for purposes of collection by the competent authority of the other Contracting State. That revenue claim shall be collected by that other State in accordance with the provisions of its laws applicable to the enforcement and collection of its own taxes as if the revenue claim were a revenue claim of that other State. [Emphasis added.] … 6. Proceedings with respect to the existence, validity or the amount of a revenue claim of a Contracting State shall not be brought before the courts or administrative bodies of the other Contracting State. … The International Tax Agreements Act 1953 (as amended in 2007) provides that the 2006 Convention between Australia and France (s 9) and the 2006 Convention between Australia and Norway (s 11M) have “the force of law”. _____________________________________________ RA/IntLaw07/Govt India v Taylor