ABSTRACT - DRUM - University of Maryland

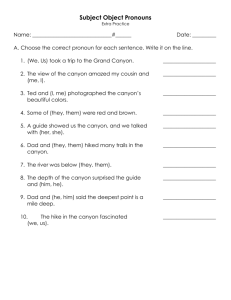

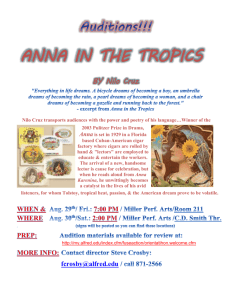

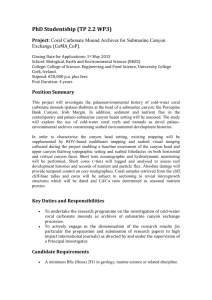

advertisement