DSE, Office of Water response to the MDBA issues paper

advertisement

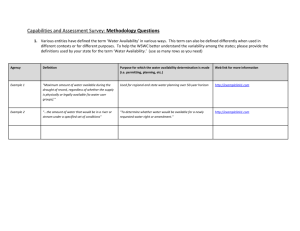

The Office of Water Department of Sustainability and Environment, Victoria submission in response to the Murray-Darling Basin Authority’s Issues Paper: “Development of Sustainable Diversion Limits for the Murray-Darling Basin” January, 2010 Contents 1. INTRODUCTION ....................................................................................................................................................... 1 2. OPTIMISING ENVIRONMENTAL, ECONOMIC AND SOCIAL OUTCOMES .................................................................... 3 2.1 MAKING TRADE-OFFS ...................................................................................................................................................... 3 2.2 ENVIRONMENT .............................................................................................................................................................. 7 2.3 ECONOMIC ................................................................................................................................................................... 7 2.4 SOCIAL ......................................................................................................................................................................... 8 3. CLARIFYING ENVIRONMENTAL ASSETS, FUNCTIONS & OUTCOMES ......................................................................... 9 3.1 DEVELOPING A LOGICAL PATH ......................................................................................................................................... 10 Logic path ................................................................................................................................................................. 10 3.2 DEFINING “KEY ENVIRONMENTAL ASSETS”, “KEY ECOSYSTEM FUNCTIONS” AND “KEY ENVIRONMENTAL OUTCOMES”........................ 12 3.3 DEFINING THE “PRODUCTIVE BASE OF THE RESOURCE” ......................................................................................................... 13 3.4 DEFINING THE LEVEL OF ASSET PROTECTION: WHAT DOES “NOT COMPROMISE” MEAN? ............................................................. 14 3.5 PROVIDING IMPROVED ENVIRONMENTAL OUTCOMES EFFICIENTLY AND EFFECTIVELY .................................................................. 15 3.5.1 USE OF WORKS ......................................................................................................................................................... 16 3.5.2 ACTIVE MANAGEMENT OF ENVIRONMENTAL ENTITLEMENTS............................................................................................... 17 3.5.3 SMART USE OF CONSUMPTIVE WATER EN ROUTE ............................................................................................................. 19 3.5.4 MANAGEMENT OF GROUNDWATER LEVELS ..................................................................................................................... 20 3.5.5 COMPLEMENTARY HABITAT RESTORATION AND MANAGEMENT ........................................................................................... 20 3.6 SETTING AN SDL IN THE FACE OF CLIMATE CHANGE ............................................................................................................. 20 4. IMPLEMENTING SDLS: RISKS AND KEY ELEMENTS ................................................................................................. 21 4.1 MECHANISM TO REACH THE SDL ..................................................................................................................................... 21 4.2 DISTRIBUTION OF IMPACT .............................................................................................................................................. 21 4.3 STRUCTURAL ADJUSTMENT ............................................................................................................................................. 22 4.4 PATHWAY TO IMPLEMENTATION...................................................................................................................................... 23 4.5 COMMUNITY INVOLVEMENT ........................................................................................................................................... 23 1. Introduction The Office of Water welcomes the opportunity to make a submission in response to the MurrayDarling Basin Authority’s Issues Paper on the Development of Sustainable Diversion Limits (SDLs) for the Murray-Darling Basin. Please note that this is not a Victorian Government submission. This Submission describes the issues that will need to be resolved in the process of setting and implementing SDLs. It also includes some suggestions to provide for environmental outcomes while minimising impacts on existing water users and regional communities. Included with this Submission is the Victorian Northern Region Sustainable Water Strategy, which was released in December 2009. The Strategy is the result of eighteen months of consultation with communities in Northern Victoria. However, it would be more properly viewed as the product of learnings accumulated over the past twenty years of water management. As such, it represents ongoing evolution of water management. It contains actions and policies to manage the consequences of prolonged drought and climate change for the environment, towns and irrigators. It deals with many of the issues that the Basin Plan was established to address and, given the significant effort devoted to improved policy and the level of stakeholder involvement in its development, we would recommend that it be given serious consideration by the Authority in developing SDLs for the Basin. The Murray-Darling Basin showcases all the values and services that water can provide. It is the most productive agricultural region of Australia. It provides the water needs for, and is home to, over 2 million Australians. It includes national parks and seven internationally recognised Ramsar Wetlands. It also holds spiritual and historic significance for all Australians. The record dry conditions in the southern Basin since 1997 have forced rapid adjustment and substantial hardship to all water users -people in towns, people on farms and the environment. Difficult tradeoffs across different water uses have been made -for communities, the economy and the environment. The uncertainties of climate change mean that all water users will need to continue to adapt to reduced water availability and reliability, and more trade-offs will be made. The Basin Plan provides the opportunity for the communities of the Basin to determine trade-offs between environmental and consumptive uses of water. Just as the increases in water allocations in the southern basin prior to 1995 caused costs to the environment, increasing allocations to the environment will impose costs to existing water users and water dependent economic activity. 1 1 Basin planning must aim to improve water security for all uses. Given the uncertainties of climate change and many substantial data gaps, the Authority is most likely to be able to do this if it adopts adaptive planning processes that: achieve healthy rivers, aquifers, floodplains, estuaries and catchments capable of delivering the wide range of water services that are valued by the community; enable communities to have access to safe, reliable and affordable water services provided at least cost; enable all water users to participate in water markets and make informed choices about the use of water; and provide transparent and consultative processes to determine trade-offs over time across environmental, social and economic needs as valued by the community. The Office of Water has worked on the development of the Basin Plan with the Authority since the Authority’s establishment, and appreciates the considerable work undertaken by the Authority to date. However, substantial work is still required to produce an implementable SDL. Specifically, the community is yet to see a statement of environmental outcomes and an evaluation of the social and economic trade-off to achieve those outcomes; or how the SDLs will be implemented consistently within the Murray-Darling Basin Agreement and Basin caps, amongst other things. The Office of Water will continue to work with the Authority as it refines its approach to the setting of SDLs. For now, this Submission is shaped around three key elements to be considered in setting SDLs: 1. the need to manage trade-offs for the use of the water resources of the Basin in a way that optimises environmental, economic and social outcomes in line with the objectives of the Water Act (Section 2): 2. clarifying the environmental outcomes and the various ways they can be provided for, including through the setting of SDLs (Section 3); and 3. addressing issues surrounding implementation of the SDLs, including risks associated with various approaches and key elements of the existing water allocation framework that need to be protected (Section 4). 1 Improved water security for all uses is required under the Water Act 2007 (Cth) see: Section 3 “Objectives of Act”; Section 20 “Purpose of Basin Plan” (which includes to promote objectives of the Act); and Section 21 “General Basis on which Basin Plan to be developed”. 2 2. Optimising environmental, economic and social outcomes The uncertainties of climate change mean that all of the Basin’s water uses will need to continue to adapt to reduced water availability and reliability. In light of this, trade-offs will need to be made across environmental, social and economic water needs if a viable, and workable, solution is to be developed. Prioritisation of any one of these needs, at the expense of any other, has the potential to undermine the Basin’s future. Further, as the examples in this submission illustrate, such an approach is not necessary. It is possible to use the Basin’s resources in a strategic way that maximises the environmental, economic and social benefits of their use. We would recommend that the Authority take this into account in setting its SDLs for the Basin. 2.1 Making trade-offs The Murray-Darling Basin is a major asset for Australia, made up of interdependent environmental, economic and social elements. However the Basin is not a natural pristine landscape, it is a managed landscape which requires continued active management. The interdependence of these elements means that management decisions affecting one element will have consequences for the other elements and thus management of the Basin needs to consider all elements together to maximise benefits to the community and to avoid unintended consequences. This interdependence is recognised in Clause 13 of the Agreement on Murray-Darling Basin Reform, which states: “The Basin Plan will also seek to improve the use and management of the Basin water resources in a way that optimises economic, social and environmental outcomes” This Clause is consistent with Clause 36 of the National Water Initiative which deals with recognising and settling the trade-offs between competing outcomes for water systems.2 In Victoria, a general process for making water resource trade-off3 decisions between classes of use and within classes has been successfully applied through the following steps: 1. define the existing water access entitlements and shares to form the basis for quantifying the effects of options to achieve the objectives; 2. draft objectives covering economic, social and environmental outcomes; 2 Schedule E of the National Water Initiative Guidelines for Water Planning, provide more detail but provides only limited assistance in making trade-off decisions (refer Clause 2 of Schedule E). 3 Many trade–off decisions are, and should be, made by individual water users through the water market, it is important that planning processes only deal with the trade-off decisions that should not be made by water users and water entitlement holders. 3 3. develop options to achieve objectives including how they would be implemented; 4. identify the impacts of options on water users, the environment and the community and identify trade-offs (costs, benefits, distributional impacts, risks vs. effectiveness); 5. seek feed-back from water users, agencies and the community; 6. revise and settle on the preferred option that includes the implementation plan that addresses distributional impacts; and 7. implement and review and adapt periodically. The Authority’s Issues Paper only partly describes the process that it will use to set SDLs and it is unclear how economic and social objectives (Step 1) will be developed and then considered in all of the subsequent steps proposed above. Also, the Paper is silent on how distributional impacts will be identified and mitigated. This step is critical to the ultimate acceptability and success of the Basin Plan. Finally, the paper is silent as to how the water quality and salinity plan will interact with the setting of the SDLs. Setting SDLs requires hard trade-off decisions because of the inevitable distributional impacts involved. Sometimes these impacts are hard to identify and they may be glossed over, however the six real life examples listed below show the potential magnitude of the trade offs involved: 1. To restore full flooding flows to Lake Albacutya, a Ramsar site, it is important to understand the volumes required. Water to fill Lake Albacutya must first flow through Lake Hindmarsh. Lake Hindmarsh must hold at least 380 GL before water commences to flow into Lake Albacutya. The Northern Mallee and Wimmera Mallee Pipeline projects will return 118 GL on average (based on historic flows) to the environment (Wimmera River, Glenelg River and a small amount across rivers in northern Victoria). However even if this could all be returned to the Wimmera River, it would be insufficient to provide for flood flows to Lake Albacutya. In the order of 800 GL would be required to fill Lake Albacutya from empty (recommended to occur about once every 8 years). In addition, the combined average annual evaporation in Lake Hindmarsh and Albacutya is 200-320 GL (depending on their capacity). Based on the extent of water use in the catchment (which has already undergone a significant reduction due to the pipeline projects) combined with significant reductions in streamflows (should dry conditions continue) it would be difficult to envisage the full environmental flow requirements of Lake Albacutya being provided. Such an SDL would be unachievable. 2. The Campaspe River floodplains have been effectively lost due to clearing, development of levee banks, and conversion to private land. Questions would need to be asked about the value of restoring overland flooding to what is now cleared private land, and the resultant changes to the community. Restoring overbank flooding would result in loss of 4 irrigation and, possibly, some town water supplies. Consequently, an SDL appropriate for the environment would have unsatisfactory consequences economically and socially. 3. High Summer flows below dams are an example where remediation costs would have an extremely high cost to address. This issue is not identified in the Issues Paper, although addressing these flows would have huge ramifications. Below irrigation dams, regulated rivers can have flow patterns opposite to those which would naturally occur because water is stored in dams in winter (when river flows would naturally be high) and then released to irrigators in summer (when rivers would naturally be drier). With fifty years of rural development and an active Interstate Water Market based on these altered flows, restricting summer flows would have dramatic effects on consumptive water supplies, and would result in: inability to meet summer irrigation demands; lower storage levels, as releases would be made more frequently; and more severe restrictions during droughts. High summer flows undoubtedly have serious environmental impacts. However they also support high value irrigation and recreation. The Goulburn River has been listed as a Heritage River - with its current set of values. These benefits need to be included in determining what environmental outcomes will be pursued in the setting of SDLs. 4. It can be possible to work within a changed landscape to achieve environmental outcomes through careful and targeted management of environmental water. While large dams have a range of well-documented negative impacts on the environment, there are actions that can mitigate impacts on the environmental water regime. One is the use of callable entitlements to provide the high flows and freshes required by the environment. The environmental releases to provide the floods at Barmah Millewa forest are a good example of this where releases of ~ 300 GL in 2000-01 and ~ 500 GL in 2005-06 had clear and measurable environmental benefits.4Storages can also be operated to provide passing flows and freshes, or releases of water during drought to top-up or freshen refuges. Additionally, the MDB Ministerial Council’s Living Murray program uses structural works to deliver water to priority areas of floodplains along the Murray River -avoiding the need to recover the thousands of gigalitres that would be needed to water the sites by re-creating floods. These options involve some environmental trade-offs, but do not compromise key Basin assets. 4 King A et al, Environmental flow enhances native fish spawning and recruitment in the Murray River, Australia, 2008. 5 5. Groundwater extraction can have multiple purposes that need to be balanced. Agricultural productivity in irrigation districts has been underpinned by management of groundwater levels through pumping. The highest volume of groundwater extraction in Victoria (check) comes from the Shepparton Irrigation Region WSPA. This has been developed for salinity control. The resource used is, in effect, recycled irrigation water that is temporarily stored in the groundwater system. In determining SDLs for such systems, the trade-off between maintaining groundwater levels for the environment and maintaining productivity for irrigation areas need to be recognised. 6. The Authority’s paper acknowledges that the majority of actions to mitigate quality problems are outside the scope of the Basin Plan (Issues Paper Section 3.8). The Office of Water is concerned that if the MDBA determines flow is a limiting factor in achieving water quality and salinity targets, that they will only look to the consumptive pool to meet these targets, rather than the most efficient measure available. For example, it is entirely possible to use water treatment facilities to meet drinking water targets at off-take sites rather than reducing SDLs. Environmental degradation in the Basin is evident, particularly in the stress caused by the current drought. That there can be insufficient water available to enable key environmental assets to survive through drought gives a clear signal that some resetting is required. However, any decisions require a full understanding of the social and economic impacts involved, and recognition that the protection of environmental assets can be achieved in a number of ways. This is discussed in more detail in the next section. The Basin Plan provides a mechanism for rebalancing water use and improving environmental outcomes, however, we also need to understand what we want from the Basin in terms of economic, social and environmental imperatives. The Productivity Commission, in its draft report on “Market Mechanisms for Recovering Water in the Murray-Darling Basin”, December 2009, has also expressed concerns regarding the setting of SDLs and the trade-offs between consumptive uses and the environment. The Commission considers that this could result in the Basin Plan over-correcting -from too little water being allocated to the environment to a situation where serious social and economic costs are imposed for small addition environmental gains. The trade-offs related to the environmental economic and social outcomes are discussed in broad terms below. Each will need to be explicitly dealt with by the Authority when setting SDLs to ensure the Basin Plan is a success. Trade-offs involve deciding upon the amount of water to be removed from consumptive purposes and allocated to the environment through SDLs. Presumably, the desired outcome will be to ensure there is a net gain to the community from the transfer to 6 environmental use. However, the Authority’s Paper does not describe what information will be used to inform this trade-off decision, or how decisions will be made. 2.2 Environment When considering SDLs to improve the environmental condition of the Basin, the Authority should aim to: focus on improved environmental outcomes, rather than a narrower objective of reducing consumptive water use; provide water entitlements to environmental managers to maximise their ability to manage and adapt environmental watering regimes to efficiently deliver environmental outcomes; provide environmental outcomes as efficiently as possible -to achieve the most benefit possible from the water available (e.g. through infrastructure or re-use of water, complementary habitat restoration); minimise and mitigate the impacts on other users of actions it takes to improve environmental outcomes; and provide for adaptive management to incorporate improved knowledge and to respond to climate change. These environmental issues are discussed in detail in Section 3. 2.3 Economic Water is a fundamental input into business and industry which provide significant value to communities. Reducing the security and reliability of supply can reduce productivity and investment, impacting on economic growth and employment in a region. Security and reliability are essential to enable market mechanisms to efficiently and effectively allocate water. Uncertainty undermines confidence and distorts efficient investment. The impact is most significant where effective water markets exist and are used by communities to manage risk, access supply and reallocate water to its highest value use. Currently, these markets provide an effective mechanism to move water from one use to another including between towns, environmental managers, industry and irrigators. Options that erode the security and reliability of existing entitlements (the products bought and sold) run the risk of creating unintended economic costs by eroding the value of the product, and destroying the confidence of participants in each states’ water entitlement regime and the water markets that are dependent on secure entitlements. Uncertainty drives away investment and encourages water users to pursue political processes to secure their water needs, rather than the market. This outcome would be inconsistent with important reforms encouraged through the National Water Initiative. 7 Sections 74 (2) and (3) of the Commonwealth Water Act suggest an intention to not only protect water access entitlements, but also to avoid a reduction in the amount of water allocated to water access entitlements. However, the Authority’s Issues Paper is less clear than the legislation and leaves the door open for reducing both the volumes of water allocated under water access entitlements and the reliability of those allocations. A further issue is the identification and mitigation of the wealth transfer impacts on existing holders of water access entitlements that might arise from setting SDLs. Any change in the volume and/or reliability of water allocations to water access entitlements will have direct and indirect wealth transfer impacts. This issue -which is discussed in the next section dealing with social issues -is not dealt with in the Authority’s Issues Paper. 2.4 Social The social value of water comes from a diverse range of uses. The most significant value is derived from its role in ensuring healthy communities but also in enhancing the quality of life through aesthetic and recreational uses, as well as where financial benefit is derived from water activities or the value of water holdings. Much of the social value derived from water is difficult to quantify. However, the chances of achieving a successful balance are maximised if the people affected by decisions are given the opportunity to participate in the decision making processes that determines the outcomes, particularly where that outcome will be sustained long in to the future. The iterative process of identifying and testing information, options and implications on which to base trade-off decisions (as described earlier) is designed to achieve this. To be successful, the process has to be applied at a scale which enables each individual to understand and consider the impacts of the proposed SDLs on their quality of life and their livelihood. Social impacts may be direct (e.g. on water access entitlements) or indirect. Indirect impacts are a particular concern for small and medium sized communities which have local economies that are dependent on water intensive business. Towns that owe their existence to the surrounding irrigation districts are likely to be particularly affected. Managing these impacts and providing adjustment support will need to be explicit within the Authority’s Basin Plan if proposed SDLs substantially reduce irrigation use in local areas which then have flow on effects to local towns and the people who live in them (see Section 4.3 “Structural Adjustment” below). In resetting water use in the Basin, we propose that the following principles are adopted: the key outcome to be provided by the Basin Plan is improved environmental outcomes, not just a reduction in consumptive water; all water use, including that used to achieve environmental objectives, will be as efficient as possible, aiming to achieve the most benefit from the available volume of water; 8 in improving environmental outcomes, impacts on other users will be minimised as far as possible and approaches will be sought to provide capacity to maximise economic production from the reduced consumptive pool; and solutions to provide improved environmental outcomes will be robust and responsive under climate change. 3. Clarifying environmental assets, functions & outcomes As stated in the Authority’s Issues Paper, one of the first steps in developing sustainable diversion limits is to understand and determine what environmental values we are seeking to protect within the Basin. Office of Water strongly supports this view, and notes their environmental values, and their associated policy objectives, can be expressed in a number of ways and achieved through various means. As outlined in more detail in section 3.1 below, clarification of these values is the priority. Once this has been settled, the most efficient way of achieving those values can be determined. Examples of how this may be done are outlined below and include the use of works and measures, and the active management of environmental entitlements. In order to minimise the impact on other water users a suite of flexible options is needed to protect the environmental values we are seeking within the Basin. In accordance with the Commonwealth Water Act, the SDL must reflect an environmentally sustainable level of take for a water resource -which means the level at which water can be taken from that water resource which, if exceeded, would compromise: a) key environmental assets; or b) key ecosystem functions; or c) the productive base of the water resource; or d) key environmental outcomes. There are a number of issues that must be resolved in the development of SDLs to meet these objectives. The first is to develop the clear logic path between environmental assets, environmental outcomes, environmental water needs and SDLs, making it clear when and if trade-offs have been made. This is discussed below in section 3.1. Following this is a discussion (sections 3.2 to 3.6) of the key issues of: defining “key environmental assets, ecosystem functions and environmental outcomes”; understanding what is meant by ‘the productive base of the resource’; defining the level of asset protection (i.e. what does ‘not compromise’ mean?); providing improved environmental outcomes efficiently and effectively; and 9 setting SDLs in the face of climate change. 3.1 Developing a logical path Given that any additional water provided to the environment is proposed to be taken from the consumptive pool -with possible economic and social impacts -it is important that the rationale for changing water uses is clear, transparent and demonstrable. The Office of Water proposes a Logic Path, set out in detail below, to achieve this. This Logic Path would provide improved environmental outcomes whilst simultaneously minimising, as far as possible, the need to reduce the consumptive pool by: defining the environmental outcomes as target flow regimes for key assets which are determined through a trade-off between the number of key assets and the level of improved environmental protection provided to them and the impact on consumptive use; providing these targeted flow regimes as efficiently as possible through: o active management of environmental water entitlements – including credit for return flows and/or use of environmental water at multiple downstream sites; o existing operating rules; o works; and o use of consumptive water en route; and setting the SDLs to provide any additional water required to meet the targeted flow regimes. Logic path 1. Identify key assets (i.e. river reaches and wetlands of high value) on the basis of their attributes which meet agreed criteria for high environmental value. This can be done at the catchment scale and, for the Murray and Darling Rivers, at the Basin scale. 2. Identify the flow regimes necessary to maintain these assets at a low level of risk. These are known as the Environmental Water Recommendations established through scientific studies and include all relevant flow components (e.g. summer and winter minimum flows, summer and winter freshes, channel forming flows, overbank and floodplain flows and groundwater dependence). They should also include what is required under different climatic conditions including dry inflow sequences. 3. For rivers, aggregate flow recommendations for assets to form a single recommended flow regime at a catchment/major tributary scale, and then assess effectiveness of this flow regime to meet flow recommendations in the Murray River/Darling River. If not adequate, the additional flow requirements should be included. For wetlands now disconnected from 10 their river systems, watering regimes should be established for each system according to the opportunity to supply water (often an irrigation supply system) and dependence on groundwater. 4. Identify the existing capability to meet these flow requirements from current environmental entitlements and operating rules, including consideration of opportunities to modify their operation. This should take into account: a. opportunities for synergistic use of water provided through existing operating rules in Bulk Entitlements in Victoria and water sharing plans in other jurisdictions; b. potential use of environmental entitlements – including those owned by jurisdictions and the Commonwealth Environmental Water Holder (CEWH); c. opportunities for efficient use of water including: targeted management of entitlements; re-use of environmental water; and capitalising on consumptive water en route; and d. opportunities to integrate groundwater and surface water management to meet overall consumptive and environmental water needs. 5. Make this assessment under different climatic conditions. Additionally, identify what complementary habitat restoration/ongoing management is required. 6. Identify the gap between available water and that which would be required to provide the environmental flow recommendations. 7. Identify the social and economic costs and benefits of providing this water. This should include impacts on local and regional communities, including urban, irrigation, domestic and stock and recreational water users in regulated, unregulated and groundwater systems. It should include direct impact as well as third party impacts. 8. Where full environmental flows cannot be provided without unacceptable impacts, identify alternatives to providing the full scientific recommendations, but which would still protect the key assets. These would include: a. reduced frequency or extent of watering, though still within the range that protects key assets, including though extended droughts; and b. use of structural works to deliver water to disconnected wetlands or floodplains rather than restoration of large and long overbank floods. In the case of floodplains, this may result in a reduction in the area that could be flooded and reduced connectivity, and whilst this includes some compromise, it would still enable key assets to be protected. These alternatives should be assessed under a range of climatic scenarios 11 9. Re-assess social and economic implications 10. Determine the target watering regime by undertaking an assessment of the environmental benefits that would be achieved by the range of potential flow regimes, the level of risk, and the social and economic costs, including costs of works and complementary restoration activities. This may require several iterations of steps 8 and 9 to achieve a sensible balance. 11. Describe target watering regimes for key assets as the environmental outcomes of the Basin Plan, clearly identifying the target assets, condition and the level of risk accepted. 12. Set the SDLs to provide the required water, identifying the product needed in terms of the optimal mix of: a. callable environmental entitlements; b. operating rules; or c. reduced extraction. 3.2 Defining “key environmental assets”, “key ecosystem functions” and “key environmental outcomes” An important step for the Basin Plan (and in the model outlined above) is defining “key environmental assets”, “key ecosystem functions”, and “key environmental outcomes”. The Office of Water does not object to the use of ‘key assets’ as the focus for the definition of environmental outcomes to be achieved through the Basin Plan. We note the criteria proposed by the Authority to establish key assets, as set out in its Issues Paper. Victoria’s criteria are described in the Victorian River Health Strategy, and in discussion papers for the revised strategy (Victorian Strategy for Healthy Rivers, Wetlands and Estuaries) and applied in Regional River Health Strategies. Victoria’s approach is to identify high value river, wetland and estuarine assets and set objectives and priorities for restoration and protection actions for these assets. These include habitat improvement, stress reduction and the application of environmental water. Ensuring alignment between the Victorian framework and the Authority’s intended approach would provide an essential link between the Basin Plan and ongoing regional river and wetland management programs. This link would enable Victoria to integrate improved flow regimes resulting from the Basin Plan with complementary habitat restoration and management activities. This is critical if improved river and wetland health are the desired environmental outcomes of the Plan. Providing improved flow regimes alone will not be sufficient to achieve improved environmental health of these systems. Aligning these processes would also ensure that information collected by Victoria and its Catchment Management Authorities (upon which DSE bases its ongoing Victorian River Health 12 Program) is relevant to the Basin Plan. This includes information on environmental assets and their environmental flow requirements, environmental water provisions and complementary habitat requirements proposed for the revision of the Victorian Strategies. Groundwater dependent ecosystems (GDEs) have varying levels of dependence on water. The type and scale of a groundwater system will influence its relationship with any GDEs. Unconfined aquifers are more likely to have a direct connection with the surface, and may provide water to wetlands and streams. Confined aquifers (such as those found in the major sedimentary basins) have less interaction with the surface and may support ecosystems within the aquifers and in areas where they ultimately discharge to the surface. Victoria has funding under the National Groundwater Action Plan to trial methodologies for assessing GDEs and incorporating their needs into management plans. This work is scheduled for completion by June 2010 and will be available to assist in the refinement of thinking about this issue after that time. In the absence of detailed information about GDEs and their significance across the Basin, the Office of Water encourages the Authority to focus its considerations on sites of national significance as described in the Issues Paper. With regard to the approach to define “functions” as outlined in the Issues Paper, we note that there is a lack of detail at this stage regarding how these would be translated into flow requirements, and hence used in determining an SDL. 3.3 Defining the “productive base of the resource” The term ‘productive base of the resource’ can be highly ambiguous. The Authority’s Issues Paper defines the productive base as the capacity of the resource to provide for a range of uses, as distinct from its actual use for these purposes. However, it could be interpreted in a range of ways – from the level of agricultural production from the resource to the measure of ecological productivity. The difference in these interpretations goes to the heart of the issue of whether SDLs should be set with some recognition of the economic and social benefits of consumptive water use in addition to environmental needs, and subsequently, whether trade-offs should be made. The Office of Water draws the Authority’s attention to the National Water Initiative where the term is first used. This definition allows for the productive base of the resource to include economic perspectives. Clause 36 of this document recognises that there are ‘trade-offs between competing outcomes for water systems’ and states that: ‘Water planning is an important mechanism to assist governments and the community to determine water management and allocation decisions to meet productive, environmental and social objectives’ [bolding added]. The Office of Water recommends the adoption of the broader definition of “productive base”. 13 3.4 Defining the level of asset protection: what does “not compromise” mean? The level of environmental protection to be provided to key assets through the Basin Plan as defined in the Water Act is that they are ‘not compromised’ by the extraction of water. This term needs to be clearly defined as its meaning will significantly impact on the quantum of water to be transferred from the consumptive pool to the environment. The term ‘not compromise’ does not necessarily mean providing water to meet full scientifically determined Environmental Water Recommendations which are aimed at protecting all key assets at a low level of risk. In Victoria, we have learnt considerably from our experience in managing rivers and wetlands in the current drought. Our approach has evolved to deal with climatic variability and the uncertainty posed by climate change. Our aim now is to ensure river and wetland assets survive during dry sequences and recover and fully function during average and wetter years (see Northern Region Sustainable Water Strategy Chapter 7 for further details). This is an approach that more closely mimics the behaviour of natural aquatic systems. The current drought has shown that for many river and wetland systems, the additional stress posed by a sequence of dry years has been too much. They have been unable to cope and as a consequence there has been significant change in their species composition or state (for example, significant river red gum death at key floodplain sites along the Murray). In many cases, these sites are approaching (or have crossed) an ecological threshold with a consequential change of state for the site. These assets have been clearly compromised and this has been made evident when they were put under the additional stress posed by the drought. The Victorian proposal for the definition of the term ‘not compromise’ is to ensure that all key assets in the Basin are provided with sufficient water to survive during dry sequences and recover and fully function during average and wetter years. From our perspective, this would include the provision of sufficient environmental water (and where necessary, works) to provide during the driest 10 year historical period: key rivers with minimum flows and dry spell breaking freshes; and key wetlands with dry spell breaking waterings. The minimum and dry spell breaking flows are aimed at minimising key threats to the assets and allowing breeding and recruitment at frequencies which are not optimal but ensure that there is no loss of species or communities. If environmental water provisions were developed to provide for this, these assets would be able to survive the drought and in wetter years would clearly have additional water to recover. This focus on survival during drought is not a ‘low bar’ for water recovery for the environment but a real recognition of the fact that aquatic systems, where there is 14 insufficient water for minimum flows and for breaking dry spells through the drought, show signs of ecological collapse. Examples of what this would mean in Victoria over the last 10 years include: the provision of summer baseflows in Broken Creek to ensure adequate water quality for Murray Cod to ensure no fish kills which had occurred in previous dry years; widespread flooding of Lindsay-Walpolla Islands at least once during the last decade (although with river flows, this would have required works); and provision of river flushes. It should be noted that this aim of survival during the driest 10 year sequence on record will require works to water a number of wetland and floodplain sites. Environmental water provisions that would meet these survival requirements would consist of high reliability entitlements (or flow rules) that in wetter years would yield enough water for system maintenance and recovery and when supplemented by lower reliability water entitlements would be sufficient to sustain key assets in the future. In addition, this focus on ensuring survival during drought provides a realistic buffer against climate change. This does not mean that the key assets of the Basin will be returned to a pristine state but that they will be able to be sustained through time in a highly variable climate. The conceptual diagram below shows the states of ecological health a river or wetland may be in and their relationship to Environmental Water Provisions. With the proposed approach above, Victoria considers that all key assets in the Basin would be in at least the 'sustainable working' state or the 'ecologically healthy' state. This is a realistic and desirable outcome from the Basin Plan. Figure 1 (removed): Conceptual example of different ecological states for rivers and wetlands Figure two (removed) shows water recovery targets and the expected benefits for river reaches and wetlands in the Northern Region of Victoria using this approach.5 Figure 2 (removed): Water recovery targets expected benefits for river reaches and wetlands in the Northern Region 3.5 Providing improved environmental outcomes efficiently and effectively A key assumption behind the Basin Plan is that the primary way of delivering improved environmental outcomes for the Basin is through setting SDLs and limiting water extraction for 5 See also the Northern Region Sustainable Water Strategy, Chapter 7, pages 133 and 134 for a more detailed discussion. 15 consumptive use. This is one essential component of improving environmental outcomes but it cannot be effective in isolation of other considerations. In fact, the SDL volume itself can be reduced given other considerations. As described in our proposed model in Section 3.1 (and discussed in further detail below) these include: the use of works to water efficiently, particularly wetlands and floodplains; active management of environmental entitlements ( i.e. held environmental water including use of carryover, credit-for-return flows or multiple use of environmental water at downstream sites); smart use of consumptive water en route; management of groundwater levels; and complementary habitat restoration and management. 3.5.1 Use of works The Living Murray program has been a learning process for defining environmental objectives, assessing the water and works required to meet those objectives and for collaboration across jurisdictional boundaries to both build works and to allocate and manage environmental water. The focus was not on achieving a specified flow in the rivers, but on achieving specific environmental outcomes, enabling approaches to be developed which achieved this with efficient use of water though use of structural works. These lessons are useful for development and delivery of the Basin Plan. They clearly show that using works to assist in watering wetlands and floodplains can dramatically reduce the water required for the environment. For example, investigations at Lindsay Island have shown that $43m of works would reduce the need for environmental water from around 1200 GL/month to only 90 GL -an order of magnitude less water for 2/3 the area inundated (i.e. ~5 000 ha of floodplain). At Gunbower, almost 5000 ha of wetlands and red gums can be flooded using only 165 GL per month, with works instead of at least 1000 GL per month without. Similar outcomes are possible at Chowilla, Pericoota-Koondrook Forest and Hattah Lakes. Whilst these works do not provide all of the ecological benefits of overbank flooding, they do have the advantage of being able to be used in all climatic conditions, including very dry years when overbank flooding would be impossible. They are therefore a robust investment which would allow these areas to be maintained even in the worst case climate change scenarios. In addition to the efficiency of works in terms of water use, for some key assets, works are the only solution to getting water to them. A number of key and high value environmental assets have been isolated from their parent rivers due to infrastructure (e.g. levee banks, roads, towns irrigation systems). For these wetland systems, works are the only way to water them effectively. 16 For other wetland and floodplain systems, restoration of overbank flooding may be theoretically possible but not practical or feasible due to serious delivery constraints, for example, the risk of flooding towns and/or private property, or storage outlet capacity. In some cases, water delivery may require, in the first instance, land acquisition. The Office of Water considers that wherever possible in the development of the Basin Plan, the use of works/actions to provide environmental outcomes efficiently and effectively should be investigated on the premise that they: minimise the call for consumptive water; enable watering within the current landscape configuration; and offer robust solutions under climate change. 3.5.2 Active management of environmental entitlements In unregulated systems, target flow regimes (as outlined above) can only be provided by rules which limit extraction at varying times of the year or limit activities which intercept water before it enters waterways. However, in regulated systems, there are several ways that environmental water can be provided to meet target flow regimes. These include: the provision of operating rules for storages which require the storage operator to release water in a planned way to meet downstream environmental needs; the provision of callable (or held) environmental entitlements which can be used with great flexibility by an environmental manager with capacity to make decisions to call water, carryover, claim credit-for-return flows and/or use it multiple times downstream and trade; or a mix of the above. Currently, there are operating rules in all regulated systems and these are being augmented by callable environmental entitlements as water is being recovered for the environment. There is some debate as to whether in the setting of SDLs to provide environmental outcomes, target flow regimes should be provided as changes in operating rules (e.g. the introduction of translucent dam rules, the forcing of more spills) or as callable (or held) environmental entitlements. The Office of Water strongly believes that additional environmental water should be provided as far as possible as callable, tradable environmental entitlements which can be actively managed by an environmental water manager. This allows environmental water to be deployed: according to actual seasonal requirements and antecedent conditions, recognising the climatic conditions at the time; 17 to a wider scope of key assets including the provision of water to wetlands and rivers through infrastructure; in conjunction with consumptive water to achieve environmental outcomes e.g. underwriting losses when consumptive water is used en route for an environmental purpose; and prioritised to ensure the best environmental outcome. This approach encourages the most efficient and smartest use of environmental water and provides a more robust and responsive arrangement in light of the uncertainty posed by climate change. The alternative to this (providing environmental water as operating rules and forced spills) will mean that rules will have to be set generally on the basis of a few high-water-demand or ‘thirsty’ assets (e.g. the Murray floodplain sites or the Lower Lakes) with the assumption that this would meet all the needs of other key assets in the Basin. This is a ‘water hungry’ and inefficient approach. In addition, it does not necessarily provide for the needs of all key assets in the Basin which include: high value rivers such as the Campaspe, Kiewa and Ovens, which have annual requirements, including minimum and maximum summer flows, and various frequencies of in channel summer/autumn and winter/spring freshes; and high value wetlands which are now isolated from river systems due to significant landscape change (e.g. Kerang Lakes) but which can be provided with water through the irrigation delivery system and works. However, these criteria do lead to identification of a very large suite of assets as key assets, and the Issues Paper appears to provide no rating system to enable further refining of “key” key assets. The Office of Water can provide details on the approach used in Regional River Health Strategies if this is considered useful. We understand that only some of these assets, the “indicator assets”, will be used to develop the modelled demands, with the expectation that this will then provide suitable flows for all key assets. The proposed indicator sites are the water hungry floodplain sites that require intermittent watering. Whether these will meet the needs of rivers such as the Campaspe, Kiewa and Ovens, which have annual requirements, including minimum and maximum summer flows, and various frequencies of in channel summer/autumn and winter/spring freshes, is not yet clear. The Authority’s proposal to establish demands for the other sites by use of the “functions” is not developed suitably at this stage to test its effectiveness. To provide transparency and rigour, the flows required to provide these functions would need to be identified. While Victoria can provide environmental flow recommendations to protect the key assets in the regulated rivers, water requirements to meet functions are not available. 18 The Office of Water’s preferred approach would be to define the level of protection required for the riverine systems (see section 3.4), and use the existing environmental flow studies to define the water requirements to provide this level of protection. While agreeing that “indicator assets” will need to be used to define demands, we request that the environmental flow recommendations (to meet an agreed level of protection) are used to assess whether the modelled SDL will provide the appropriate flows. The Office of Water believes that the Basin Plan should provide target flows for all key assets and that this is best done by providing as far as possible, callable, tradable environmental entitlements for discretionary use by an environmental water manager. A concern in the use of operating rules and forced spills is that it would rely too heavily on the southern regulated system to supply the Lower Murray system, as these needs would have to be built into the operating rules of the major storages. Historically, flows from the Darling system whilst more unpredictable, have played a vital role in maintaining the lower Murray system. These should be still protected and utilised as far as possible and supplemented with use of environmental entitlements in the southern connected system whenever necessary to provide improved environmental outcomes in the Lower Murray. A further concern of the Office of Water is that the identified indicator assets are not indicative of all Basin assets. Wetlands isolated from river systems are currently unlikely to be included, and while pragmatic, it is not a principled approach and a rationale needs to be provided as to what is “in” and what is “out”. With regard to key assets, functions, productive base and key environmental outcomes there is minimal detail provided in the Issues Paper on how objectives and targets would be set. The provision of more detail by the Authority would allow for greater comfort around what the modelled flow regimes would be, and what they would achieve. However, the Office of Water is keen to engage with MDBA further on all of the matters outlined in this section. 3.5.3 Smart use of consumptive water en route There are real opportunities in the MDB system to utilise consumptive water en route for environmental outcomes. This is particularly the case with Inter-Valley Transfer water. Wherever possible, consumptive water should be used to deliver environmental benefits providing there are no third party impacts. Again, this allows achievement of environmental objectives with a reduced call for consumptive water. Victoria is preparing guidelines to govern the process to formalise existing arrangements to provide certainty for the environmental water manager, while still ensuring flexibility for the system operator. The guidelines will also encourage new opportunities to be actively sought. Operating 19 arrangements for the use of consumptive water for environmental benefits will be formalised through existing planning processes, such as the environmental programs in bulk entitlements.6 3.5.4 Management of groundwater levels There are opportunities to use adaptive approaches such as groundwater level management to improve security of groundwater dependent ecosystems. In addition to management to a volume, the capacity to set target aquifer levels to maintain flows to GDE’s can be an effective management approach. Any restrictions to groundwater use can be based on risk to a GDE, optimising the use of the groundwater storage. 3.5.5 Complementary habitat restoration and management As discussed above, flow is a key determinant of improved environmental outcomes but is not the only one. The key environmental assets need to be managed in a way that achieves environmental targets and this includes complementary water quality, habitat restoration and land management. The Victorian approach of aligning the objectives and priorities for key assets in our Regional River Health Strategies with the Basin Plan provides a mechanism to ensure that this complementary management occurs and maximises the chances of achieving the desired environmental outcomes. 3.6 Setting an SDL in the face of climate change Setting meaningful SDLs in the context of climatic change is extremely challenging. With the uncertainty that the community is facing, it is very risky to set rigid targets based on either the historical climate or modelled predictions. To manage effectively in this context, the best approach is to establish a flexible and adaptive approach to managing water: this would include establishing a regime where water managers can actively direct water to the most valuable environmental use, and build in the ability to review water management as information improves. Victoria’s approach, as set out in its Northern Region Sustainable Water Strategy, is to establish a system of flexible environmental entitlements which can be moved across the state, either through infrastructure or by trade, to their most valuable use.7 Water recovery targets are established to provide healthy rivers under historic flow conditions, but which would also enable protection of drought refuges under high climate change scenarios. This enables immediate protection of high 6 Northern Region Sustainable Water Strategy, Chapter 7, page 140 7 Northern Region Sustainable Water Strategy, Chapter 2, page 76 20 value assets through long dry periods. As information on the implications of climatic change on assets and objectives improves, the water management requirements will be reviewed. Likewise for groundwater, protection of GDE’s through use of target groundwater levels provides a more adaptive response to changes in climate. Any restrictions on use are developed and agreed through the planning process and regularly reviewed. 4. Implementing SDLs: risks and key elements 4.1 Mechanism to reach the SDL Once the volume of the SDL has been identified, a mechanism is required to secure it. The Office of Water is firmly of the view that any mechanism to secure water needs to protect the integrity of Victoria’s existing water entitlement and allocation framework. Protecting the integrity means retaining the reliability of entitlements and the security of water products. This is essential to allow a healthy water market to continue to operate, which we consider to be critical in any approach to implementing the SDL. For a market to operate, people must have confidence in the reliability of the product. A functioning market, with clearly defined products, including clearly defined reliability of supply, is necessary to enable water users to manage their own risks by confidently using market mechanisms. This is especially important in light of the current uncertainty about the severity and implications of climate change. By maintaining the reliability of entitlements as a secure product, markets will be able to function and water holders will be able to manage their own risks. High reliability water products in particular are an extremely valuable and sought after product. They underpin urban water supplies and high value horticulture, where an interruption to supply cannot be tolerated. They also underpin rural and regional economies, especially in times of drought. Implementing the SDL by, for example, reducing security of supply would have a severe impact on the integrity of products and the confidence of users to participate in the markets and, consequently, for the market to effectively establish a value for water. As well as effecting urban and rural communities, reducing the security of high reliability water will also effect environmental water held by the environmental water holder. This would necessitate a greater recovery of water to make up for this loss. It is also the long held view of the Office of Water that any increases to environmental entitlements should be protected by a subsequent reduction in the relevant cap on consumptive use. 4.2 Distribution of impact The starting point is very important in determining how SDLs will be implemented. 21 For example, Victoria currently accesses 37% of the water resources from the Murray River system, even though Victoria and NSW are entitled to a 50% share of the River Murray Flows (after accounting for South Australia). This is a consequence of the Murray-Darling Basin cap. The cap was not based on scientific study, but was set at the volume of water that would have been diverted under 1993-94 levels of development. As the cap was set at the level of extractions at a point in time, it picked up and embedded anomalies between jurisdictions because extractions by NSW were higher than extractions by Victoria at that time. Consequently, the NSW cap for the Murray River system is 400GL more than for Victoria for neither scientific, economic, social nor hydrological reasons. It is the Office of Water’s view that existing cap levels are not a valid starting point for the development of sustainable diversion limits. As a further example, there is no formal sharing agreement for groundwater between NSW and Victoria. In the connected aquifers of the Riverine Plain and upper Murray, there are substantially different approaches to groundwater extraction, with NSW having much higher extraction volumes than Victoria. Any development of SDLs needs to be consistently developed so that such anomalies are balanced. Good management should reflect the actual need to revise extraction policies where that is it required. 4.3 Structural adjustment No matter how they are configured, SDLs will have structural adjustment implications. These will affect all individuals, communities and regions to a greater or lesser extent. There will be an economic impact on those who use water for productive purposes, or who are in any industry that adds value to that production. There will be social impacts as a result of changes to water availability for household or community use, and as a result of changes to viability of towns in a changed irrigation landscape. Depending on the extent of change required to implement the SDL, some level of structural adjustment will be required. The costs and potential impacts need to be determined through discussions with affected communities. The Office of Water agrees with the National Water Commission finding in 2009 that: Despite considerable recent and valuable work to improve understanding of structural adjustment, the Commission considers that there is insufficient understanding of the processes and causes of structural adjustment and a paucity of data at the necessary spatial and temporal scales to enable effective monitoring of adjustment. The Commission is concerned about this lack of understanding, 22 as the success of the overall national water reform process will ultimately depend on how well the adjustment process proceeds in irrigation-dependent communities 8 As a minimum essential support in this regard, the Basin Plan needs to include an explicit process to enable transition when the SDLs are implemented. For the Basin Plan to identify the social and economic impact of the proposed SDL, and hence to develop a strategy for transition, a clear understanding will be needed of the local and regional impacts. This would need to include regulated and unregulated systems, and the different user groups – which include those benefiting from urban, irrigation and domestic and stock supplies, as well as recreational users. Co-ordination is also required with the Commonwealth Government’s Water for the Future program which has committed $3.1 billion over 10 years to purchase water in the Murray-Darling Basin. The Commonwealth intends to spend $2 billion on water by mid 2012. The total value of permanent trade in Victoria in 2007/08 was estimated to be $277 million making the size of the Commonwealth’s intended purchase seven times Victoria’s 2007/08 market turnover. This water purchase will force adjustment in addition to that being felt from reduced rainfall. It is critical to Victoria that the Commonwealth maintains the integrity of the market as much as possible. Once SDLs are set, they must be used to guide Commonwealth purchases. 4.4 Pathway to implementation In addition to determining the magnitude of the SDL, the Basin Plan will need to provide a clear and feasible pathway to put in to practice any required changes to current water availability. For practicality of implementation, this pathway should enable compatibility with existing state water management frameworks and should enable reconciliation with the Murray-Darling Basin Agreement. Clarity is also required around accountability for implementing the changes; and support or compensation to enable required changes. The Commonwealth’s role in defining details of the mechanism to implement the SDLs, and for structural adjustment, also needs clarification. 4.5 Community involvement In the face of any potential changes to water management that affects peoples’ livelihoods, Victoria undertakes a rigorous process of engagement and consultation. Communities are a rich source of 8 National Water Commission, Australian water reform 2009, Second biennial assessment of progress in implementation of the National Water Initiative, Chapter 10 – Structural Adjustment and Water Reform (page 201), Finding 10.9. 23 information about their regions and are best placed to help us understand the implications of tradeoffs in water management. Community involvement takes time, but without the knowledge and support of communities, managed change will not happen. The Office of Water is committed to a rigorous process of consultation with rural communities, water corporations, catchment management authorities and representative organisations. For instance, in developing and delivering the Northern Region Sustainable Water Strategy, the Department undertook an 18 month consultation process that was led by a consultative committee, supported by 4 working groups and was delivered right into the heartland of regional communities. The Northern Region Sustainable Water Strategy was a two way process that focused on face to face communication via the boards and irrigators' water service committees of the various water corporations and catchment management authorities, special stakeholder briefings, and presentations to farming, environmental industry, government and tourism groups. This was punctuated by a series of media briefings and media releases to inform the broader public of the development of the Strategy, and advertising during specific periods where public comment was sought. While engagement with local communities is intensified through the development of major water policies/strategies, there is ongoing communication between government and its irrigators/regional communities. This is facilitated by water corporations and catchment management authorities’ boards and the water services committees/implementation committees. For example GoulburnMurray Water has twelve Water Services Committees established to advise the Board and represent customers in its six irrigation areas, private diverters, groundwater users and domestic and stock customers. Based on this experience, the Office of Water notes that appropriate and thorough consultation is crucially important for gathering community knowledge, informing trade-off decisions and ensuring community acceptance of any new water management arrangements that are proposed to be implemented. Given the significance of the Basin Plan and SDLs for the Basin communities, thorough consultation and community input will help facilitate acceptance and understanding of what the Authority is proposing to implement. Flexibility in implementation, particularly when the first Basin Plan is rolled out, would allow for this, and also provide scope for the Authority to address any adverse or unacceptable impacts. 24