Non-academic Impact of Research through the Lens of

advertisement

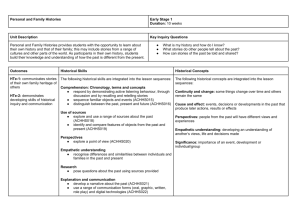

DRAFT DRAFT DRAFT Non-academic Impact of Research through the Lens of Recent Developments in Evaluation J. Bradley Cousins1 University of Ottawa, Canada Paper presented at the conference ‘New Frontiers in Evaluation’, Vienna, April 2006 1 Contact: J. B. Cousins, Faculty of Education, University of Ottawa, 145 Jean Jacques Lussier, Ottawa, ON, CANADA, K1N 6N5; email: bcousins@uottawa.ca DRAFT DRAFT DRAFT Non-academic Impact of Research through the Lens of Recent Developments in Evaluation What is the role of research evidence in policy formulation relative to the wide array of forces that operate within the policy arena? The answer to this question is undeniably complex. Prunty describes policy making as “the authoritative allocation of values” (1985, p. 136) or statements of prescriptive intent that are rooted in normative propositions and assumptions about societal issues. Policies are likely to be “determined by what policy makers see as ideologically appropriate, economically feasible and politically expedient and necessary.” (Jamrociz & Nocella, 1998, p. 53). Knowledge for policy (Linblom & Cohen, 1979) may be understood in terms of its explicit or declarative dimensions (knowledge that can be stated) and as well as its tacit or procedural aspects (knowledge of how to do something without being able to articulate how). Tacit knowledge has been equated with craft expertise and thought of as being an important trait of a skilled practitioner. It is also relied upon quite heavily in the policy formulation process. Of course, explicit knowledge is promoted as being central to conceptualizations of evidence-based policy (Nutley, Walter & Davies, 2003). One source of evidence for evidence-based policy making is research. Typically, social sciences and scientific knowledge is generated in the academic sector through funded and unfunded pure and applied research activity. Consistent with longstanding academic traditions, such knowledge is integrated into the academic knowledge base, but increasingly, forces among granting agencies (e.g., government, foundations, donors) marshal to ensure relevance for policy decision making. Interest has moved from funding individual studies toward funding programs of research. In some cases, funding agencies elevate proposals for research programs that include an element of interdisciplinarity and that privilege connectedness with the non-academic, especially, policy community. As a result of such interest in augmenting the relevance of research to policy making, understanding knowledge transfer and how to assess the non-academic impact of research is increasingly capturing the attention of funding agencies and academics alike (Davies, Nutley & Walter, 2005; Landry, Amara & Lamari, 2001; Nutley et al., 2003; Pawson, 2002a, 2002b). It has long been understood that, how research evidence factors into policy development is a function of the multidimensional and non-rational dynamics of the policy process (Lindblom, 1968; Lindblom & Cohen, 1979; Weiss, 1980). As such, the challenges of evaluating the non-academic impact of research are significant. 1 DRAFT DRAFT DRAFT . Evaluation shares many of the same tools and methods that are used in social sciences research, yet the two differ in fundamental ways. Social science research may be differentiated from evaluation on contextual (Hofstetter & Alkin, 2003) or valuing (LevinRozalis, 2003; Scriven, 2003/2004) dimensions. First, evaluation is typically defined as systematic inquiry to judge the merit, worth or significance of some entity. Judgement implies comparison. Observations or systematically collected data are necessarily compared against some thing. For example, in program evaluation, observations about the program might be compared against program performance at an earlier point in time, against the performance of a group that is similar to the program group but that does not receive the program, or against some external standard or benchmark. In research, no such requirement for judgement exists. A second distinction is that despite remarkable overlap in methods with social science research, evaluation by definition is context-bound; knowledge is produced for a particular purpose for a particular set of users in a specific context. While social science research can have significant uses and influences in the community of practice or policy making, its use is not context bound in the way that evaluation knowledge would be. For this reason, the “applied versus basic research dichotomy … does not adequately capture the evaluation-research distinction” (Alkin & Taut, 2003, p. 3, emphasis in original). Presently, we are interested in the problem of evaluating the non-academic impact of research. In a symposium on the topic sponsored by the Economic and Social Research Council (ESRC) in the UK in May 2005, four related purposes of such evaluation were identified: Accountability – providing an account of the activities and achievements of the unit being assessed (such as a funding agency or a research programme); Value for money – demonstrating that the benefits arising from research are commensurate with its cost; Learning – developing a better understanding of the research impact process in order to enhance future impacts; Auditing evidence-based policy and practice – evaluating whether policy and practice … is using social science research to support or challenge decision making and action. (Davies et al., 2005, p. 5) These purposes are comprehensive and resonate well with traditional conceptions of use and impact including instrumental (support for discrete decisions), conceptual (educative function) and symbolic (persuasive, legitimizing function) (Landry et al., 2001). 2 DRAFT DRAFT DRAFT In the ESRC symposium, participants identified an array of approaches and methodological issues and choices and articulated the complexities involved in understanding the process of research impact. The outcomes of the deliberation were captured well in the Davies et al. (2005) report. While this document undoubtedly advances thinking in the area, underrepresented in my view are recent developments in evaluation as a domain of inquiry that may lend themselves to addressing at least some of the challenges inherent in understanding research impact in non-academic settings. In this paper I explore potential contribution to such understanding of developments in three specific areas: collaborative inquiry processes, conceptualizations of evaluation use and influence, and unintended consequences of evaluation including its potential for misuse. I selected these developments because they all relate in some way to understanding the use of evaluation and/or evaluation consequences. I conclude by summarizing some thoughts about how such considerations might benefit the challenge of evaluating the non-academic impact of research. Collaborative Processes in Evaluation Whether traditionalistic approaches have yielded centre stage to emergent perspectives in evaluation is a matter for debate, but the rise of collaborative, participatory and empowerment approaches (Cousins, 2003; Fetterman & Wandersman, 2005), democratic-deliberative frameworks (House & Howe, 2003; Ryan & Destefano, 2000), and culturally sensitive evaluation choices (Thompson, Hopson & SenGupta, 2004) is undeniable. Collaborative inquiry is relevant to the challenge of evaluating the non-academic impact of research because pragmatic applications have been shown to foster the use of evaluation findings (and use of process – to be discussed below) (Cousins, 2003). In the domain of research use, prior research and theory have focused on the concept of sustained interactivity between members of the knowledge user and the knowledge producer communities (e.g., Huberman, 1994). The establishment and exploitation of contacts between these communities throughout the process of research promises to have desirable effects in increasing the likelihood that the research would be taken up in the non-academic community. Moveover, the chances of mutual benefit or reciprocal influences are heightened; researchers stand to benefit from deeper understandings of the context of use and the needs of intended users which may in turn influence design choices, questions addressed, and the like. 3 DRAFT DRAFT DRAFT But collaborative evaluation approaches imply a more direct relationship and one that I would argue ought to be considered seriously in the context of evaluating the impact of research because they have been shown to foster evaluation utilization (e.g., Cousins, 2003). Central to these approaches is the working relationship between members of the trained evaluation community and members of the community of program practice. In the case of assessing the non-academic impact of research we might include as members of the community of practice at least the following: Researchers and their colleagues who produce research-based knowledge – Increasingly we are seeing that contributors to a research program are from a variety of disciplines and that roles range from professors or academics, to research associates, research collaborators, and students; Policy makers and developers who are the potential beneficiaries of the knowledge produced – Policy makers may be elected officials but would also include public servants and members of government bureaucracy, whether federal, state or local; Research program sponsors – This would include government funding agencies such as ESRC, foundations or even corporations. Special interest groups – Lobbyists and advocates wanting to influence policy themselves belong to this category. Such advocates may be working to support identified causes (e.g., anti-smoking activists) or to counter the influence of such activists on the basis of competing issues or values (e.g., tobacco companies, hospitality service associations). Out of this work have emerged conceptual frameworks for understanding the collaborative processes between trained evaluation specialists and professional, practicebased and community-level stakeholder groups. In some of our prior work we endeavoured to conceptualize the collaborative inquiry process (Cousins & Whitmore, 1998; Weaver & Cousins, 2004). Weaver and I (2004) revised and earlier version of a framework for conceptualizing the collaborative inquiry process (Cousins & Whitmore, 1998) by unbundling one of three dimensions and ultimately arriving at a set of five continua on which any collaborative inquiry process could be located. The five dimensions are: Control of technical decision making (evaluator vs. non-evaluator stakeholder) – Who controls such decision-making? Is control garnered by members of the research 4 DRAFT DRAFT DRAFT community, by members of the non-researcher stakeholder community or is it balanced between the two? Diversity of non-evaluator stakeholders selected for participation (limited vs. diverse –How diverse is the range of stakeholder interests among the participants? To what extent is inclusiveness promoted to maximize the potential that all important perspectives are represented? Power relations among non-evaluator stakeholders (neutral vs. conflicting) – Do those with an important stake in the evaluation vary in terms of their power to enact change? To what extent are relations among the different groups conflict-laden? How aligned are the interests of the participating groups? Manageability of the evaluation implementation (manageable vs. unwieldy) – To what extent do logistical, time and resource challenges impede the manageability of the research process? Is it feasible? Unwieldy? Depth of participation (involved in all aspects of inquiry vs. involved as a source for consultation) – To what extent do non-researcher stakeholders participate in the full spectrum of technical research tasks, from planning and shaping the research; to data collection, processing and analysis; to interpretation, reporting and follow up? Is their participation limited to consultative interactions or do participants engage directly in all of the technical research tasks? Using the revised version in a “radargram”, we showed hypothetical differences in form among conventional stakeholder-based evaluation, and two forms of participatory evaluation, practical and transformative (see Figure 1). We then independently analyzed two case examples of participatory evaluation using the framework. In each case, the collaborative inquiry was described using the radargram, which helped to reveal differences and points of convergence between them. In another application, I analyzed an array of case reports of empowerment evaluation projects using this device (Cousins, 2005). The results revealed considerable variation over the independently implemented empowerment evaluation projects. –– Insert Figure 1 about here –– My suggestion is that this conceptualization of collaborative inquiry stands to benefit the evaluation of non-academic impact of research in at least the following ways. First, 5 DRAFT DRAFT DRAFT addressing the questions associated with each of the five dimensions at the point of planning the evaluation would help to focus attention on the important aspects to be considered. We are of the view that the framework is comprehensive in capturing the essential elements of effective collaborative inquiry. Second, the framework would be useful retrospectively in evaluating the implementation of the collaborative evaluation of research impact. To what extent was the collaborative inquiry successful in striking the appropriate balance between evaluator control and input from non-evaluator stakeholders? Were members of the latter group effectively involved in the inquiry? Was the group homogeneous or highly diversified and were there implications for the manageably of the inquiry? The dimensions provide guidance for the development of indicators of the inquiry process and the indicators could then be used to describe and characterize the evaluation process. Third, measured indicators of the collaborative process could then be related to measures of non-academic research impact, shedding light on the nature of collaboration that is likely to be effective in this context. We now turn to recent developments in the study of evaluation use and influence and consider their relevance to the problem of evaluating the non-academic impact of research. Conceptions of Use and Influence Among those interested in evaluation utilization, the concept of process use – as distinct from the instrumental, conceptual and symbolic use of findings – has emerged as a powerful mode of understanding impact. In addition, some evaluation scholars have extolled the merits of moving ‘beyond use’ in favour of a theory of influence (Kirkhart, 2000; Mark & Henry, 2004; Henry & Mark, 2004). I will consider each of these developments in turn. Process Use: In evaluation circles, Patton’s concept of process use (1997) has come to the fore and has stimulated much interest on several levels. Process use is defined as effects of the evaluation in the stakeholder community that are independent of its findings. In essence, by virtue of their proximity to the evaluation – whether through ongoing consultation, dialogue and deliberation, or through direct participation in it as in collaborative evaluation – stakeholders develop knowledge and skills associated with evaluation logic and methods that may benefit them in other ways. Process use can take on various manifestations. First, evaluation can enhance communication within an organization by sending a clear message to the community about what elements of program are important to investigate. Second, evaluative inquiry can take the form of interventions with the purpose of improving 6 DRAFT DRAFT DRAFT the program while examining it. Third, the evaluation processes can be used to engage program participants in their work in more crucial ways (e.g., reflection, discrimination, logical analysis). Finally, the process can lead not only to individual, but to group and even organizational development. Regardless, process use is a concept that moves the study of impact of inquiry beyond the focused assessment of uptake of findings. The concept has been operationalized and studied empirically. For example, in a large scale survey, Preskill and Caracelli (1997) observed evaluators’ self-reported user benefits and effects of evaluation were attributable to the process of user participation in or proximity to the evaluation. Russ-Eft, Atwood and Egherman (2002) carried out an evaluation utilization reflective case study within the American corporate sector. Despite the apparent non-use of findings in their study, the authors identified several process uses of the evaluation: supporting and reinforcing the program intervention; increasing engagement, selfdetermination, and ownership; program and organizational development; and enhancing shared understandings. In a more recent exploratory study of process use within the context of the Collaborative Evaluation Fellows Project of the American Cancer Society, Preskill, Zuckerman and Matthews (2003) concluded that evaluators should be intentional about process use and that stakeholders should understand learning as part of the evaluation process. Process use has also found its way into theoretical formulations about integrating evaluation into the organizational culture (Cousins, 2003; Cousins, Goh, Clark & Lee, 2004; Preskill & Torres, 1999). Developing the capacity to learn by virtue of proximity to evaluation logic and processes can occur at the individual, group or organizational level. Evaluation playing a role in developing organizational learning is considered by some to be an instance of process use (e.g., Cousins, 2003; Cousins et al., 2004). Of course, considerations about developing a culture of evidence based policy and practice are very much of concern to those interested in augmenting the uptake of research. I would suggest that the likelihood of such organisational cultural change would be increased if process use were recognized and embraced as a legitimate concept within the domain of inquiry of research impact. The direct involvement of non-evaluator stakeholders in the evaluation of research impact – researchers, sponsors, end-users – may imply considerable costs. But research on process use of evaluation reveals that non-evaluator stakeholders need not be directly involved. Huberman’s (1994) notion of increasing the mutuality of contacts between the knowledge production community and the user community would seem to apply. 7 DRAFT DRAFT DRAFT I would assert that the endeavour to understand at deeper levels the non-academic impact of research would benefit from targeted interest in process use of its evaluation. From Use to Influence: This brings us to another recent development within evaluation that may be of interest in the broader research use domain. Some theorists in evaluation are now advocating the expansion of thinking beyond use to theories of evaluation influence and they have even identified process use as examples of evaluation influence. Kirkhart (2000) critiqued theory and research on evaluation use on a number of fronts. Among her chief concerns are a narrow focus on an inappropriate imagery of instrumental and episodic application and attendant construct under-representation. She maintains that models of use imply purposeful, unidirectional influence, and that an broadened perspective is required in order to more fully and completely understand evaluation impact. Kirkhart advocates abandoning use in favor of a theory of influence. She proposes a conceptual framework of utilization that consists of three fundamental dimensions: source of influence (evaluation process, evaluation results), intention (intentional use, unintentional use) and time (immediate, end-of-cycle, long-term). A theory of influence, according to Kirkhart, would permit: (1) tracking of evolving patterns of influence over time; (2) sorting out conceptual overlap between use and misuse (by expanding conversations about misuse and illuminating beneficial and detrimental consequences of influence); (3) improving the validity of studies of evaluation consequences (by dealing with the problem of construct under-representation); (4) tracking the evolution of evaluation theory; (5) comparing evaluation theories; and (6) supporting theory building through empirical tests of evaluation theory. In two significant papers, Henry and Mark recently extend thinking about a theory of influence in important and complex ways (Henry & Mark, 2003b; Mark & Henry, 2004). They acknowledge and accept many of Kirkhart’s arguments and use her initial framework as a platform for further conceptual development and contribution toward a theory of influence. One of their concerns about alleged conceptual constraints inherent in models of use is that research productivity has been hampered. Henry and Mark cue on Kirkart’s temporal dimension and provide an elaborate development of possible pathways of influence that would follow from the sources of influence (evaluation process or findings) and intention (intended or not) dimensions. They add to her argument and framework of evaluation influence by highlighting the many social change processes that can result in influence, showing how interim outcomes can facilitate longer term outcomes and how change mechanisms can serve to create complex pathways of 8 DRAFT DRAFT DRAFT processes and outcomes. In their most recent article (Mark & Henry, 2004) they reframe a prior conception of utilization (Cousins, 2003) as a logic model or theory of evaluation influence. Outputs and outcomes in the model are characterized in a two dimensional matrix of “level of analysis” (intrapersonal, interpersonal, collective) and “type of mechanism” (general, cognitive/affective, motivational, behavioral). No less that 31 suggested potential outcomes appear within the 12 cells of this matrix, all supported by research as elaborated in Henry and Mark (2003). Whether evaluation ought to move beyond theories of use to a theory of influence is a matter for debate. For example, Taut and Alkin (2003) argue that to understand all possible impacts of evaluation we need a broad framework, such as those developed by Kirkart and Henry and Mark, but the question of “how and to what extent the process and findings of an evaluation lead to intended use by intended users is a more narrow, yet equally important question” (p. 8). Many evaluation influences, they argue, are unquestionably important but are unintended and must be addressed after they have occurred, whereas practicing evaluators have to do their best in actively ensuring and promoting evaluation use, while at the same time noting evaluation influences that might occur but which are outside of their sphere of action. Another concern has to do with Henry and Mark’s question as to why evaluators would be guided by the goal of maximizing use in the first place. “Use is inadequate as a motivation for evaluation because it fails to provide a moral compass … and falls short of recognizing and promoting the ultimate purpose of evaluation as social betterment.” (Henry & Mark, 2003, pp. 294-295). Regardless, important contributions arising from this work warrant serious consideration in the context of evaluating the non-academic impact of research. Specifically, Mark and Henry’s concepts of “level of analysis” (intrapersonal, interpersonal, collective) and “type of mechanism” (general, cognitive/affective, motivational, behavioral) provide a comprehensive framework for considering the impact of research and the notion of pathways of influence moves us beyond the linear frameworks for thinking about research use that have traditionally characterized inquiry of this sort. This approach has a great deal to offer in terms of capturing the complexities of the context for use (Davies et al., 2005) and provides a platform for thinking about a wide array of intended and unintended consequences or impacts. The framework could be used proactively to design tracer studies of research impact, permitting a well reasoned assessment of the sorts of variables that ought to be taken into account. It could also serve as a basis for retrospective analysis of research impact, in more or less of a backward mapping approach. The notion of 9 DRAFT DRAFT DRAFT intentionality is another important dimension for consideration. Moving beyond use to a theory of influence broadens the net for capturing intended and unintended effects. We now turn to other work that has been done in evaluation that embraces the notion of intentionality more directly. Unintended Consequences Ideas about evaluation ‘misuse’ and ‘unintended consequences’ of evaluation are of increasing interest. Cousins (2004) recently built on prior work to develop a framework for understanding the misuse of evaluation findings. Unintended consequences of evaluation, whether positive or undesirable, can be located on a continuum ranging from unforeseen to unforeseeable according to Morrell (2005) in a recently published, penetrating analysis on the topic. We will examine each of these in sequence. Misuse: A stream of inquiry in evaluation use has to do with the misuse or inappropriate use of evaluation findings, an area to which Alkin and Patton have made considerable contributions, respectively. Patton has long argued that fostering intended use by intended users is the evaluator’s responsibility. He also proposes that: as use increases so will misuse; policing misuse is beyond the evaluator’s control; and misuse can be intentional or unintentional (Patton, 1988, 1997). Others started to think about evaluation misuse in serious ways: how to define it? Identify or observe it? Track it? (see, e.g., Alkin, 1990; Alkin & Coyle, 1988; Christie & Alkin, 1999). My own distillation of some of these ideas is captured in Figure 2 (see also Cousins, 2004). –– Insert Figure 2 about here –– The Figure is divided into four quadrants by two orthogonal dichotomous dimensions corresponding to the intended user’s choices and actions: (1) Use – evaluation findings are either used or not used; and (2) Misuse – evaluation findings are either handled in an appropriate and justified manner or they are not. Patton (1988), who initially proposed these dimensions, used the terms ‘misutilzation’ and ‘non-misutilization’ as opposite sides of the same coin for the latter. In the first quadrant we have the best case scenario, ‘ideal use’, where evaluation findings are used in legitimate ways to support discrete decisions (instrumental), foster learning (conceptual), or symbolize, persuade or legitimize (political). 10 DRAFT DRAFT DRAFT In quadrant 2, evaluation misuse results either as a consequence of evaluator incompetence (unintentional) or evaluator mischief (intentional). In quadrant 3, evaluation data are suppressed by the evaluator for inappropriate reasons and in the final quadrant (4), data are not used for justifiable reasons (e.g., they are known to be faulty, they are supplanted by competing information). As we observed elsewhere (Cousins & Shulha, in press), scholarship on evaluation misutilization is virtually devoid of empirical inquiry. While misutlization is relatively easy to define in the abstract, studying it empirically is quite another matter. While it would be difficult to implement empirical field studies on misuse, due to obvious ethical considerations (not to mention methodological challenges), a framework of this sort might be useful in simulated or contrived contexts. The framework was applied, for example, in a retrospective analysis of a hypothetical case depicting an ethical issue confronting an evaluator (Cousins, 2004). The framework might also be used proactively for planning evaluations that would maximize the desirable outcomes (quadrant 1) and at least heighten awareness about some potential pitfalls that might lead to undesirable outcomes (quadrants 2 – 4). In comparing evaluation use to its cognate fields, including research use, we (Cousins & Shulha, in press) also observed, that while the topic of misuse has received only limited attention in the evaluation domain, we are unaware of scholarship on this construct in the context of research use. Undoubtedly this is in large part due to the fact that evaluation is context-specific and end-users are typically known. One can imagine unknown downstream users distorting evaluation evidence to their advantage or otherwise behaving in unethical ways with regard to their use of evaluation findings. Such is possible within the realm of research use as well. Forward tracking methods and retrospective analyses would represent possible methodological approaches to get at such issues, but some complications arise. First, in evaluation, standards of practice that have been developed and validated by professional associations exist (e.g., American Evaluation Association, see Shadish, Newman, Scheirer & Wye, 1995), and at some level might serve as a check on the quality and legitimacy of evaluation evidence. Although academic standards and cannons for doing research exist, these would be less visible than evaluation professional standards and therefore less accessible as a benchmark with which to evaluate the integrity of the research product. A second consideration concerns whether or not evaluation data were unjustifiably suppressed. Given the distance of policy makers from the source of research knowledge production and that policy is based on such a wide range of considerations, including ideology, economics and political expediency (Jamrociz & Nocella, 1998) not to mention other sources of 11 DRAFT DRAFT DRAFT evidence, one would be hard pressed to imagine a case of non-use of research as representing an instance of misuse. Even in the context of evaluation, suppression of findings may reside in a grey area between being ethically questionable, on the one hand, and politically astute, on the other. Nevertheless, the framework does offer some preliminary thinking about research misuse and it may benefit from further consideration and development within this milieu. Unintended Consequences: Figure 2 provides some interesting thoughts about the identification of appropriately used evaluation findings and potential misuses and abuses of them. But it does not explicitly get at the issue of intentionality, the way, for example, that Kirkart’s framework of evaluation influence does. Of course, ideal or appropriate uses that were identified in advance would be considered intentional. They fit into what Patton (1997) calls ‘intended uses but intended users’. But other appropriate uses might arise that were not at all intended. An example might be an impact evaluation that concludes that a program is worthy of continuation but also serendipitously calls into question a previously unrecognized flaw in program design. The reconfiguration of the program design would be an appropriate and positive outcome of the evaluation. We might also think about less than honourable uses of evaluation as being intentional or unintentional depending on whether they arise as a matter of naiveté or mischief. Recent work in evaluation explores the concept of intentionality from a slightly different yet potentially useful slant. In a very elaborate and well developed paper, Morrell (2005) lays out a framework that considers the problem of conceptualizing the unintended consequences of programs. He categorizes unintended program consequences into two distinct classes: the ‘unforeseen’ and the ‘unforeseeable’. Unforeseen consequences are unintended consequences, good or bad, that “emerge from weak application of analytic frameworks and from failure to capture the experience of past research….unforeseeable consequences stem from the uncertainties of changing environments combined with competition among programs occupying the same ecological niche” (Morrell, 2005, p. 445). While unforeseen consequences are not always possible to anticipate in advance due to such forces as resource and time constraints, they are, in theory, within the realm of possible anticipation. The same cannot be said about unforeseeable consequences which would arise from unpredictable change in the environment or within the program itself. In any case, whether unforeseeable or not, the assumption is that it would be desirable to minimize unintended consequences, particularly those which turn out to be negative. Even in the case of positive unintended consequences undesirable effects may arise. Morrell’s framework 12 DRAFT DRAFT DRAFT assumes organismic, ecological and systemic parameters. Hence a change of one sort (or valence) has the potential to lead to a change in another and that change will not necessarily be positive. Morrell lists several tactics or strategies that program developers and evaluators can use to minimize unintended program consequences. These are summarized in Table 1. –– Insert Table 1 about here –– We can see in the Table that several strategies are available to evaluators to detect unforeseen consequences, assuming adequate time and resources. While some of these such as life cycle dynamics, building on what is known, and planning methodologies, capitalize on already available information, some are associated with broadening the spectrum of interests informing the evaluation by involving interdisciplinary teams or invoking processes that permit group or perspective expansion. Minimizing unforeseeable consequences, on the other hand, is very much about change detection. Evaluation must be flexible enough to assume that logic models are dynamic and evolving and that environmental conditions are not static. Early change detection can help to alert evaluators as to inquiry design changes that would enable emergent program consequences to be adequately measured and monitored. Some of the recommended strategies are tied quite directly to versatility in methods, ongoing monitoring and evidence-based decision making. Also, the installation of an advisory body is recommended as a way to ensure wide coverage of potential issues and changes arising from program implementation and effects. The strategies identified by Morrell (2005), particularly those associated with detecting changes that may lead to the identification of unforeseeable consequences, have considerable potential for tracking the non-academic impact of research. Many of these resonate well with approaches that have already been identified as being potentially fruitful (Davies et al., 2005; Ruegg & Feller, 2003). Because they were developed within the realm of program evaluation, some of them rely quite directly on process considerations. For example, reliance on program logic models – developed a priori in the case of unforeseen consequence minimization, and as new changes emerge in the context of unforeseeable consequence minimization – features prominently among strategy options. Yet in the context of evaluating the non-academic impact of research, process considerations may be less often emphasized, at least not to the degree suggested by Morrell. Would it be fair to say that reliable and realistic program logic models could be developed to depict the intended 13 DRAFT DRAFT DRAFT workings of a research program? Why not? Yet such an approach has not be seen, at least by me. Another consideration is the reliance on the integration of varying stakeholder perspectives into the evaluation process, through, for example, involving interdisciplinary teams, building on what is already known, group processes, knowledgeable pool of advice, and future markets. These strategies are appropriate whether the goal would be the minimization of unforeseen or unforeseeable consequences. Such strategies reaffirm the case made earlier for serious consideration of collaborative and participatory approaches to the evaluation of non-academic impact of research. Summary and Conclusions Summary: In this paper I recognized the focus for evaluation – the non-academic impact of research – to be distinct from the usual fare in program evaluation, but I suggest that recent developments within evaluation as a realm of inquiry have much to offer in terms of advancing approaches to the evaluation of research use. There is no question that the challenges of tracking and evaluating the impact of research on policy, program and organizational change poses special and unique problems and challenges. But I have taken the position that the development of potential solutions to such problems would do well to be informed by recent developments in the domain of inquiry of evaluation, which by definition and in comparison with inquiry on research use and knowledge transfer, is largely concerned with more tangible, local and accessible contexts for use. To that end, I reviewed three primary recent developments in evaluation, each bearing some, mostly direct, relationship to the study and practice of enhancing evaluation use. First, I gave consideration to developments in collaborative evaluation, an approach that is congruent with several emergent approaches in evaluation including empowerment, democratic-deliberative and culturally sensitive evaluation. Collaborative, and especially participatory, approaches have been shown to foster evaluation use, in some cases to quite powerfully (Cousins, 2003). I presented a framework that identified five distinct dimensions of the participatory process and has proven useful as a conceptual tool in the retrospective description and analysis of collaborative inquiry projects (Weaver & Cousins, 2004). I proposed that the tool would be useful in the context of evaluation of research use, to the extent that non-evaluator stakeholders (e.g., researchers/knowledge producers, policy makers/end-users of research) are involved in the evaluation process. The argument for 14 DRAFT DRAFT DRAFT adopting collaborative approaches to the evaluation of research impact is buttressed by other developments in evaluation, summarized below. I then described recent developments in the conceptualization of evaluation use. One such development is the concept of process use, which can occur at the individual, group or organizational level. Process use – non-evaluator stakeholder benefits that accrue by virtue of proximity to evaluation – advances our understanding of use beyond traditionalistic use-offindings conceptions. It ties in well with the proposal put forward by some colleagues to move beyond a theory of use to a theory of influence in evaluation (e.g., Kirkhart, 2000; Henry & Mark, 2003). A theory of influence has the potential to more adeptly capture evaluation consequences that may be related to the process or attributable to findings that are, perhaps, unintended or, at least, unanticipated. A significant advantage of the theory of influence perspective is the concept of pathways of influence and its implications for research designs on use and influence that would be more powerful in representing the complexities of consequences of evaluation in context. These developments have implications for the evaluation of research use, particularly given the complexities inherent in non-academic user communities such as the policy arena. I carried the notion of intentionality further by describing two frameworks that have been recently developed in association with unintended consequences of evaluation. The first is a framework for considering the misutilization of evaluation (Cousins, 2004) that targets end users of evaluation and their potential for inappropriate action on the basis of misunderstanding or mischief. Admittedly, the applicability of the framework to the case of research misuiltization is limited in that end users are not often readily identifiable. Nevertheless, the framework provides food for thought and speaks to the notion of intentionality. Further extension on that notion derives from a framework for unintended consequences of evaluation, developed by Morrell (2005) that features a continuum of unforeseen and unforeseeable consequences and a set of tactics for minimizing both. This framework seems more directly relevant to the problem of tracking the non-academic impact of research. Proposals for Consideration: By way of concluding the paper, I wish to offer a set of proposals, rooted in the foregoing discussion, which I believe have great potential to advance our understanding of the how to augment desired non-academic impact of research. I present seven such proposals in no particular sequence. At the outset I draw attention to potentially significant implications for costs and practical logistics but I hasten to add that I was not guided by such considerations in developing these ideas. If we are serious about enhancing 15 DRAFT DRAFT DRAFT the link between research and policy/practice and moving more completely to organizational cultures of evidence-based policy, than such practical considerations would require further deliberation and debate. My first proposal is that evaluators of research use embrace models of collaborative inquiry and employ such approaches a great deal more than is presently the case. Collaborative approach ought to be considered partnerships between evaluators of research use and non-evaluator stakeholders. Members of the partnership contribute different things: evaluators contribute knowledge and expertise in evaluation and standards of professional practice; non-evaluator stakeholders contribute knowledge of research program logic and dynamics and of the context within which such programs operate. The Weaver and Cousins (2004) framework could be a valuable aid to choice making concerning the design and implementation of collaborative approaches. Whether or not non-evaluator stakeholders are involved directly or in a consultative mode, they have much to contribute and their input should be exploited. Second, I propose that evaluators of research use continue to use innovative research methodologies that are sensitive to the exigencies of tracking non-academic impact of research. To be sure, excellent repositories and reviews of such innovation have been made available in recent years, those covered by Ruegg and Feller (2003) and Davies et al. (2005) being most notable and laudable. But others may be added, some arising for Morrell’s interesting paper on understanding unintended consequences of use. His list of approaches is very comprehensive and imaginative and worth serious consideration. Mark and Henry’s (2004) framework for pathways of influence provides another thought provoking basis for designing research not only on the consequences of evaluation but, as well, the impact of research in non-academic settings. A third proposal for consideration that I would offer is that evaluators of research use expand their conceptions of utilization to incorporate the dimension of process use or benefits to non-evaluator stakeholders that are quite independent of research findings and would accrue by virtue of proximity to the research. This notion resonates well with Huberman’s (1994) conception of sustained interactivity which implicates the augmentation of contacts between the knowledge producer and user communities. The closer that knowledge users are to the production process, the more likely such benefits would be to accrue. And, most importantly, such benefits are likely to be essential elements of serious attempts to move organizational cultures toward evidence-based policy and decision making. Another consideration would be reciprocal effects on researchers and research with the likely effect of 16 DRAFT DRAFT DRAFT increasing responsiveness to the information needs of policy and decision makers (Huberman, 1994). Another consideration, fourth on my list, is that evaluators of research use should take steps to augment their understanding of and sensitivity to unintended consequences of research, particularly its misuse. While this would provide considerable challenge, conceptual frameworks developed by Cousins (2004) and Morrell (2005) provide some guidance at least in terms of constructs worth thinking about. Of course the grey area between unethical or unjustifiable use of inquiry and politically adept use would be even more difficult to clarify within the context of research use as opposed to evaluation use. Nevertheless, such issues are most certainly worth serious attention. Fifth, many current approaches to the evaluation of research impact, focus on consequences and outcomes, while paying relatively little attention to process. Recent approaches to evaluation have embraced the concept of program theory and developing and using logic models to guide inquiry. This approach could be adapted to the context of evaluation of research use. I would propose that the development of logic models or theories of research program logic would be both relatively easy to do and would provide clear guidance for the evaluation of research impact. In this way, approaches to such evaluation could move beyond more or less ‘black box’ approaches to at least ‘grey box’, if not ‘clear box’, alternatives. My sixth proposal is that the frameworks that have been described and discussed above could and should be used in both retrospective and prospective ways. Evaluators of research impact would do well to use conceptions of collaborative inquiry, research misuse, and unintended consequences, for example, in retrospective analyses or post mortems of research impact. But considerable purchase might be derived from proactive use of these frameworks to inform, perhaps, research program design. As such, the power and potential of longitudinal designs to better understand and trace research impact could be exploited to a much higher degree than is presently the case. Finally, I would propose that empirical research on research impact be augmented. While a good deal of empirical work exists (e.g., see Cousins & Shulha, in press; Landry et al., 2001), such research has not been informed by the recent developments in evaluation presented in this paper. While the development of elaborate conceptual frameworks is undeniably an important step and clearly intellectually stimulating, more needs to be known about the veracity of such conceptions in practice. Virtually all of the frameworks addressed in this paper could easily be used to inform the design of empirical inquiry on research use. 17 DRAFT DRAFT DRAFT The results of such research would be invaluable in helping to refine and adapt recent developments in evaluation to the evaluation of research use in non-academic contexts. References Alkin, M. C. (Ed.). (1990). Evaluation debates. Thousand Oaks: Sage. Alkin, M. C., & Coyle, K. (1988). Thoughts on evaluation misutilization. Studies in Educational Evaluation, 14, 331-340. Alkin, M. C., & Taut, S. (2003). Unbundling evaluation use. Studies Educational Evaluation, 29, 1-12. Amara, N., Ouimet, M., & Landry, R. (2004). New evidence on instrumental, conceptual and symbolic utilization of university research in government agencies. Science Communication, 26, 75-106. Christie, C. A., & Alkin, M. C. (1999). Further reflections on evaluation misutilization. Studies in Educational Evaluation, 25, 1-10. Cousins, J. B. (2004). Minimizing evaluation misutilization as principled practice. American Journal of Evaluation, 25, 391-397. Cousins, J. B. (2003). Utilization effects of participatory evaluation. In T. Kellaghan, D. L. Stufflebeam & L. A. Wingate (Eds.), International handbook of educational evaluation (pp. 245-265). Boston: Kluwer. Cousins, J. B., Goh, S., Clark, S., & Lee, L. (2004). Integrating evaluative inquiry into the organizational culture: A review and synthesis of the knowledge base. Canadian Journal of Program Evaluation, 19(2), 99-141. Cousins, J. B., & Shulha, L. M. (in press). A comparative analysis of evaluation utilization and its cognate fields. In B. Staw, M. M. Mark & J. Greene (Eds.), International Handbook of Evaluation. Thousand Oaks: Sage. Davies, H., Nutley, S., & Walter, I. (2005, May). Approaches to assessing the non-academic impact of social science research. London: Economic and Social Research Council. Fetterman, D., & Wandersman, A. (Eds.). (2005). Empowerment evaluation principles in practice. New York: Guilford. Jamrozik, A., & L, N. (1998). The sociology of social problems: Theoretical perspectives and methods of interpretation. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press. Henry, G. T., & Mark, M. M. (2003). Beyond use: Understanding evaluation’s influence on attitudes and actions. American Journal of Evaluation, 24, 293-314. 18 DRAFT DRAFT DRAFT Hofstetter, C., & Alkin, M. C. (2003). Evaluation use revisited. In T. Kellaghan, D. L. Stufflebeam & L. A. Wingate (Eds.), International handbook of educational evaluation (pp. 189-196). Boston: Kluwer. House, E. R., & Howe, K. R. (2003). Deliberative, democratic evaluation. In T. Kellaghan, D. L. Stufflebeam & L. A. Wingate (Eds.), International handbook of educational evaluation (pp. 79-100). Boston: Kluwer. Huberman, A. M. (1994). Research utilization: The state of the art. Knowledge and Policy, 7(4), 13-33. Kirkhart, K. (2000). Reconceptualizing evaluation use: An integrated theory of influence. In V. Carcelli (Ed.), The expanding scope of evaluation use. New Directions in Evaluation, No 88 (pp. 5-24). San Francisco, CA: Jossey Bass. Landry, R., Amara, N., & Lamari, M. (2001). Utilization of social sciences research knowledge in Canada. Research Policy, 30, 333-349. Levin-Rozalis, M. (2003). Evaluation and research: Differences and similarities. Canadian Journal of Program Evaluation, 18(2), 1-32. Lindblom, C. E. (1968). The policymaking process. Upper Saddle River, NJ: Prentice Hall. Lindblom, C. E., & Cohen, D. K. (1979). Usable knowledge: Social science and social problem solving. Newhaven CT: Yale University Press. Mark, M. M., & Henry, G. T. (2004). The mechanisms and outcomes of evaluation influence. Evaluation, 10, 35-57. Morrell, J. A. (2005). Why are there unintended consequences of program action, and what are the implication for doing evaluation? American Journal of Evaluation, 26, 444463. Nutley, S., Walter, I., & Davies, H. (2003). From knowing to doing. Evaluation, 9, 125-148. Patton, M. Q. (1988). Six honest serving men. Studies in Educational Evaluation, 14, 301330. Patton, M. Q. (1997). Utilization-focused evaluation: A new century text (3rd ed.). Thousand Oaks, CA: Sage. Pawson, R. (2002a). Evidence-based Policy: In search of a method. Evaluation, 8, 157-181. Pawson, R. (2002b). Evidence-based Policy: The promise of 'realist synthesis'. Evaluation, 8, 340-358. Preskill, H., & Carcelli, V. (1997). Current and developing conceptions of use: Evaluation use TIG survey results. Evaluation Practice, 18, 209-225. 19 DRAFT DRAFT DRAFT Preskill, H., & Torres, R. T. (1999). Evaluative inquiry for learning in organizations. Thousand Oaks. CA: Sage. Preskill, H., Zuckerman, B., & Matthews, B. (2003). An exploratory study of process use: Findings and implications for future research. American Journal of Evaluation, 24, 423-442. Prunty, J. (1985). Signposts for a critical educational policy analysis. Australian Journal of Education, 29, 133-140. Russ-Eft, D., Atwood, R., & Egherman, T. (2002). Use and non use of evaluation results: Case study of environmental influences in the private sector. American Journal of Evaluation, 23, 19-32. Ryan. K.E & DeStefano, L. (Eds.), Evaluation as a democratic process: Promoting inclusion, dialogue, and deliberation. New Directions in Evaluation, No. 85, (pp. 312). San Francisco: Jossey-Bass. Ruegg, R., & Feller, I. (2003). A toolkit for evaluating public R & D investment: Models, methods, and findings from ATPs first decade. Washington: National Institute of Standards and Technology. Shadish, W., Newman, D., Scheirer, M. A., Wye, C., & (Eds.). (1995). Guiding principles for evaluators. New Directions in Evaluation. No.66. San Francisco: Jossey-Bass. Scriven, M. (2003/2004). Michael Scriven on the differences between evaluation and social sciences research. Evaluation Exchange, 9(4), 4. Thompson-Robinson, M., Hopson, R., & SenGupta, S. (Eds.). (2004). In search of cultural competence: New Directions in Evaluation. No. 102. San Francisco: Jossey-Bass. Weiss, C. H. (1980). Knowledge creep and decision accretion. Knowledge: Creation, Diffusion and Utilization, 1, 381-404. 20 DRAFT DRAFT Depth Manageability Control 5 4 3 2 1 DRAFT Diversity P-PE T-PE SBE Power Figure 8-1: Hypothetical dimensions of form in collaborative inquiry (adapted from Weaver & Cousins, 2004) 21 DRAFT DRAFT DRAFT Use 2. Misuse 1. Ideal Use Mistaken Use Instrumental Use (incompetence, uncritical acceptance, unawareness) Conceptual Use Mischievous Use Symbolic/Persuasive Use (manipulation, coercion) Misuse Legitimate Use Abuse Rational non-use (Inappropriate suppression of findings) Political non-use 3. Unjustified Non-use 4. Justified Non-use Non-use Figure 2: Intended user uses and misuses of evaluation findings 22 DRAFT DRAFT DRAFT Table 1: Summary of Tactics Dealing with Unforeseen and Unforeseeable Consequences (adapted from Morrell, 2005) Unforeseen Consequences Unforeseeable Consequences Life cycle dynamics: can be used to model program and identify relevant variables Extend internal monitoring: evolving logic models, open ended qualitative methods to detect change Interdisciplinary teams: combine diverse perspectives with views of a core group of stakeholders Environmental scanning: low-cost methods to detect source of change Building on the already known: exploit history, literature review Futures markets: aggregating independent knowledge, belief and intuition. Planning methodologies: multiple scenario, assumption-based, back-casting approaches Retrospective logic modelling: construct logic after the fact thereby basing design decisions on observations and evidence Temporal, causal distance: shorten distance between innovation and outcome Data: flexibility, multipurpose data source usage Group processes: expand group size through methods such as Delphi Technique Knowledgeable pool of advice: advisory boards, expert panels, peer review.