Cognition and semiotics – from sensation to dialogue

advertisement

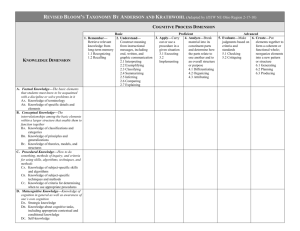

Cognition and semiotics – from sensation to dialogue © Flemming Ask Larsen 2009 One of the major challenges we face when dealing with cognition in general is that cognition is only accessible via interpretation from behaviour. When we seek to assess cognitive ability of people, who perform almost no linguistic behaviour (here people with congenital deafblindness), this challenge is even greater. Regardless if we are concerned with neurological, neuropsychological, psychological, sociological, educational, or developmental issues we need to map a theoretical model of cognition onto some observable behaviour in order to get access to cognition. This leaves us with three very intriguing challenges. Firstly, we need to have a good theory about cognition. Secondly, it is crucial to our results how we understand behaviour. Thirdly, it is important that we have a method of observation that will embrace behaviour as an expression of cognition in a manner that includes the full complexity of the theoretical understanding of cognition as well as the full range of contextual influences on the situated instance of ongoing cognition that we observe. These three challenges imply some quite complex semiotic tasks that are intimately interconnected. On the one hand we need a theoretical model that describes the dynamical parameters underlying cognition, and a way of analysing the mapping of these parameters onto the observation. Setting up such a paradigm of observation cues, and the mapping of these cues onto the behaviour is a semiotic task that should not be taken lightly. On the other hand we need a phenomenological approach to understanding behaviour, that is reliable and at the same time operational. This entails a semiotic analysis of the ongoing social and dialogical interaction in terms of how the situation and the actions within that context are understood by the participants. Especially when dealing with people with cdb, this is an important and not at all straight forward semiotic task. 1 These two tasks are connected in the sense that one does not work without the other. In order for us to understand ongoing cognition, we need to apply a theory and a method that allow us to integrate the two approaches while exploring the online cognition of the person with cdb and their partners. One of the reasons for this being a complex matter is the fact that we do not know all of the global dynamic parameters that govern cognition. This means that we cannot apply classical mathematical, forced dynamic, or cause relational descriptions of the phenomenon. Instead we must apply local descriptions of qualitatively different states in terms of how crucial parameters are organized, and then deduct from the organization of these parameters in the individual states to underlying hidden process that lead to the observed change in state. René Thom (Thom 1972 from Stjernfeldt 1992 p51ff) put up a general model of how such very complex phenomena (systems) can be addressed. According to Thom, we need a set of parameters in a set of propositions P. Then every state in the process can be described by a set of these propositions. If one state A transforms into another state B then the process that results in this transformation can be described by deducing the set of parameters b for B from the parameters a that described the first state A. Graphically Thom shows it like this: Figure 1 (Thom 1977 from Stjernfeldt 1992 p53) A process B parameterization system parameterization a deduction b P In other words, the deduction from a to b is the only way in which we can describe the process from A to B in a scientifically valid manner. That set up very high demands for the quality of the propositions in P. The task of parameterization of a set of states in a complex system and the deduction of the change is a qualitative analytical task. 2 The dynamics of ongoing cognition If we apply this way of understanding the description of complex systems to ongoing cognition we can set up a simple model based on our knowledge from neuropsychology and the science of meaning analysis. From the study of neurological processing we know, that cognition is a two way process. We integrate information that is taken in by our sensory systems in a bottom-up process, and at the same time we focus and organise this information according to existing neurological structures in a top-down control of the process. In semiotic terminology these two interrelated processes are what we call structures in the world that influence and restrain our meaning making (bottom-up), and mental conceptual and schematic structures that we project onto the world in order to make sense of it (top-down). This would be a good place in the text for a discussion with Gadamer (1960), and his concepts of “Vorverständnis” and ”Wirkungsgeschichtliches Bewusstsein”, which are other notions of preconceptualisations that we bring into the situation. But limitations in space prevent this discussion to be unfolded here. Another relevant contribution would be a discussion with the dialogists and the notion of “third parties” (Cf. Markova 2006). Both of these scholars are concerned with cultural and biographical historical context that we carry around, integrated in our minds as memory, as a consequence of our participation in culture. The cognitive semiotic notion presented here is concerned with ongoing meaning making, and the pre-conceptions that are to be taken into consideration are divided into (at least) two different domains. One is the here-and-now scenario, which is equivalent to the Base Space in the semiotic tradition from Brandt and on (Cf. Brandt & Brandt 2005). The other domain is partly in line with Gadamer and Markova, and is operationalised in the 6-spacer (Ask Larsen 2003 and 2006) in the Memory space. But memory is also to be considered on another level, namely a more schematic level, as it is developed in the research on cognitive semantics and bodily schematics (Eg. Talmy (2000) and Lakoff & Johnson (1999)). We end up with two distinct phenomenological spaces – Base Space and Memory Space (Ask Larsen 2006) – from which all structure as well as all of the juicy content is to be recruited into the meaning construct. The two-way process of meaning making is what results in experienced meaning. 3 In addition we know from the study of meaning, that we cannot escape coherence. If coherence is not provided by the world, we will project schematic structure top-down in order for coherence to be maintained/restored. If coherence is not achieved, we do not experience meaning, but instead a frustrating sense of not-understanding. Following this line of thought, we always carry with us an understanding of the world. Ongoing cognition will then be a matter of integrating new occurrences in the world with the meaning construction that is already active. This integration may be more or les automatic depending on how easily the new occurrence fit into the understanding of the here and now. Some occurrences are unconsciously integrated in the existing meaning construction. These are insignificant to the understanding. A good example of this kind of conceptual integration is physical activities such as walking. Once you have learned how to walk, the repeated occurrence of the floor beneath your feet will not cause any changes in how you conceptualise the walking. The better you know an activity, the less you need to focus on the different sub-aspects of its unfolding, and more aspects of the task can be performed automatically, without the energy expensive use of attention. The better you are at walking, the less mental energy it acquires. Other occurrences put up more resistance, and must be dealt with more actively in order for coherence to be maintained. This kind of occurrences will tend to influence the overall conceptualisation, and give rise to a change in the understanding of the situation as such. Such changes may be of varying significance. Some changes will just be modifications within the understanding of the situation, while others will rearrange much more of the conceptual structure in order for coherence to be maintained. An example of the former could be the arrival of new guests to a small dinner party, which might influence what kind of topics that are suitable. An example of the latter could be the ringing of the school bell, which dramatically changes the definitions of everybody in the classroom from silent listening pupils and a lecturing teacher to highly socially interactive children and a baffled grownup taking refuge in the coffee room. In this case we have a drastic change in the understanding of the situation from it being a lecture-scenario to it being a getting-of-from-school-scenario, with all of the redefinitions of self in relation to others that such a scenario-shift offers. 4 Below is a schematised version of this analysis of ongoing cognition with the three qualitatively different processes sketched out: The Automatic, the significant, and the unsuccessful cognition. Figure 2: Automatic, significant and unsuccessful cognition 1 Time Significant cognition Automatic cognition Scenario A Unsuccessful cognition Scenario A Scenario A Scenario A ? Scenario A Scenario ??? Scenario B ! ! ! When we, in this way, understand the significant new elements as a kind of barrier to the maintenance of coherence (cf. Ask Larsen 2004 p. 6), it becomes clear that we need to establish situations that the person with cdb is familiar and comfortable with, before we introduce such barriers for the understanding. In other words, we need to balance the unknown against the known. Testing this balance is testing cognition. 1 The first sketch for this model was made for a seminar at Conrad Svensen Senter in Oslo that I held together with the Norwegian special pedagogue Gunnar Vege in 2005. It has been developed to its present form during the intermediate years through presentations by the author at the courses on co-creating communication with persons with cdb at NUD, and at the lectures at the international masters’ programme on communication and cdb at University of Groningen (and other places). It is published here for the first time. 5 Working memory In order to exemplify the above we can consider the cognitive ability that is described as working memory. When we attempt to assess ongoing cognition, the recognition and observation of working memory is quite a complex matter. First of all memory in general is only observable when applied on some task where the recollection of memory is influencing the performance of the task. Likewise, working memory is only observable as actions that take into consideration what is believed to be active in working memory, in order for some specific task, or part of such task, to be performed optimally. This again must be backed up by a good description of what the task is about, and how it may be performed more or less optimally according to the different degrees of applied working memory. On top of all of this, we must consider, whether the person that we are trying to assess is at all attempting to perform the task that we describe. Thus we need to be sure about that person’s intentions, which in itself is quite a complex analytic task. It is fair to say, that the ongoing use of working memory is a system that is not at all possible to describe in a classical mathematical manner. Therefore we need to apply a model of the kind that Thom suggests. First of all we need to find task that is organizes in such a way, that there may be at least two outcomes: One successful and one that is unsuccessful. In doing so, we must make sure, that it is possible to distinguish the failure of working memory from other possible explanations for the failure of performing the task. The task must be motivating for the person undertaking the task. This is to ensure, that it is not lack of intention to perform the task that lead to the failure. In addition, the task must be understood by the person in question. Failure of understanding the task or the presentation of the task may be another reason for failure of performing the task. Another problem that poses itself is how we make sure, that what we think occupy working memory are actually the right things? As Anne Nafstad pointed out on the network seminar on which this publication is based2, deafblindness in itself puts a lot of pressure on working memory. When things in the environment are not accessible via perception, the environmental context will necessarily take up some of working memory. This leaves us with quite a complex semiotic problem when dealing with people that we cannot simply ask about their intentions and understanding: How can we distinguish between failure Working seminar of Network on Assessment of Cognition in relation to Deafblindness – From Sensation to Dialogue, NVC Denmark, Dronninglund February 2-4, 2009. 2 6 because of failing working memory, failure because of lack of understanding, and failure because of lack of motivation? This problem leaves us with no other option than to set up parameters for assessing understanding and intention as well as working memory. In addition to this, we need a way of accounting for the possibility, that the pressure of perceiving the environment on working memory is not what causes the failure of performing the task. This leaves us with the problem of how to assess this environmental pressure. On top of all of this come all the other cognitive functions that are involved in performing tasks in general, such as attention span, processing speed, executive function, action planning, just to mention the most obvious ones. Analysing contextualised actions From a semiotic point of view, the most fruitful way of addressing the complex matters of cognition, is to perform our analyses on the level of the contextualised action itself. The different cognitive functions are all derived from action performance, and are in combination an attempt of a theoretical parameterization of cognition as such. We can thus never assume that some of the parameters (e.g. motivation or understanding) are fixed in a given situation, but we must always account for these parameters in an analysis of the contextualised actions that we consider as data. Finding good data, with actions where motivation and understanding is easily agreed upon as high, is a high priority task. This is what we in the field of deafblindness talk about as optimising the situations (e.g. the communication and the conditions for perception), before even beginning to assess anything (Cf. Andersen & Rødbroe 2000, Temahæfte 3 p11f). The analysis of the data is per definition a semiotic analysis, no matter how we perform it, in the sense that we attempt to map out the cues that shows us how the participants (agents) conceptualise the situation. The difficult twist on this task is how to describe these conceptualisations from within a set of structured dynamical parameters (P in Thom’s model above). The 6-space model (Ask Larsen 2003 and 2006) is an attempt to set up such a structured set of parameters that might help explicate some of the conceptualisations that underlie the actions of the participants. In combination with analyses of the conceptual complexity of the situations and actions in terms of the structural and schematic complexity of these situations (cf. Ask Larsen & Nafstad 2006), this 7 kind of analysis may account for the degree of understood conceptual complexity of the actions, and thus help us in assessing what level of cognition is performed in different situations. In order for us to come to an understanding of cognition from observing behaviour, we must first of all understand how the specific behaviour makes sense for the one who performs the actions. When we cannot simply ask the person in question, we must analyse this conceptualisation from the actions themselves. This kind of analyses is semiotic interpretation. By making these interpretations as motivated as possible we can set up good hypotheses about the cognitive abilities and potentials of the person we are trying to assess. All other kinds of assessment of cognition are likewise based on interpretation of actions. We in the field of deafblindness just need more analysis than what is normally needed, because we need to analyse many of the parameters that are normally accounted for by linguistic instruction of, or report from, the participants. This paper have argued that assessing cognition is never a simple matter of counting a number of failed or successful actions, but is always woven into a complex system of mental and environmental context that has to be accounted for in the analysis. The qualitative interpretation from the successfulness of the action to the cognitive ability always need to be based on a good theory that embrace the whole human condition, and is to be performed in a highly analytical manner. Especially when dealing with such difficult circumstances for assessing cognition as is provided by deafblindness, we need to be theoretically and analytically well informed. This goes for cognition and human behaviour, as well as for the theory of and analysis of meaning. Referencer: Andersen, Karen & Rødbroe, Inger (2000): Identification af medfødt døvblindhed – Et diagnosticeringsmateriale, Videncenter for Døvblindfødte, Dk. Ask Larsen, Flemming (2006): Mental space theory – an introduction to the 6-spacer, in CNUS No. 7, www.nud.dk/cnus Ask Larsen, Flemming (2004): Den uforståelige, den meningsfulde og den betydningsfulde oplevelse in Døvblinde-Nyt Nr. 2, 2004 pp. 4-7, Videncenter for Døvblindfødte, Dk. Ask Larsen, Flemming (2003): The Washing-Smooth Hole-Fish: And other findings of semantic potential and negotiation strategies in conversation with congenitally deafblind children, 8 MA thesis, Centre for Semiotics, University of Aarhus, Denmark (available as CNUS No. 9 at www.nud.dk/cnus) Ask Larsen, Flemming & Nafstad, Anne Varran (2006): Døvblindfødtes sproglighed: Et dokumentations-projekt, Skådalen Publication Series No. 23, Oslo. Brandt, Line and Brandt, Per Aage (2005): Making sense of a blend – A cognitive semiotic approach to metaphor, research paper, Centre for Semiotics, Århus, Denmark. http://www.hum.au.dk/semiotics/docs2/pdf/brandt&brandt/making_sense.pdf Gadamer, Hans-Georg (1960): Wahrheit und Metode. Grundzüge einer philosophischen Hermeneutik, 3. Aufl., Tübingen 1972 Lakoff, George & Johnson, Mark (2000): Philosophy in the flesh: The embodied mind and its challenge to western thought, Basic Books, New York. Marková, Ivana (2006): On the “Inner Alter” in Dialogue in International Journal for Dialogical Science, Spring 2006. Vol 1, No. 1, pp. 125-147. Stjernfelt, Frederik (1992): Formens betydning – Katastrofeteori og semiotik, Akademisk Forlag, Dk. Talmy, Leonard (2000): Toward a Cognitive Semantics, Massachusetts, USA. 9