Yen-Ju Chen Professor: Hui-Shan Lin Optimality Theory 29 May

advertisement

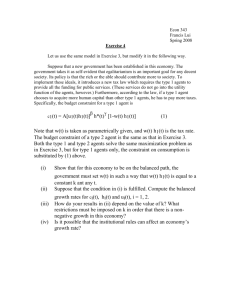

Yen-Ju Chen Professor: Hui-Shan Lin Optimality Theory 29 May 2009 Reduplication in Optimality Theory: A Case of Hakka Reduplication Chapter One Introduction This paper explores the possibility of adequately representing the relationship between morphology and phonology in Optimality Theory. We know that there are rules sensitive to morphological properties, phonological properties independently. And there are also some rules particular to morphological-phonological interface. Of course we know that these rules are explanations based on the central claim of rule-based phonology. In this paper, we adopt the claim of Optimality Theory that phonological outputs are generated not from rules, but from an interaction of different constraints. The actual phonological output is the one that is optimal with respect to the ranking of different constraints in particular language. According to this claim, we go on to consider a possibility to change the rules we refer to in the front into different constraints in a view of Optimality theory. Not only the rules sensitive to phonological rules, but also rules sensitive to morphological rules, we would love to see them adequately represented in the framework of Optimality Theory. We consider that since morphological rules are related to some actual phonological outputs, we could not leave them behind. But since these outputs are associated with some kind of morphological properties, it would be inadequate if we analyze them only in a phonological perspective. And Optimality Theory is a theory with many insightful views in phonological field. Its way to use different constraints is a step to reach universal phonological properties. Although different languages contain different sets of constraints, but constraints are universal, in other words, there is no constraint can be used in only one particular language. And any constraint can be considered as a reflection of one universal phonological property regulating phonological output, as either faithfulness constraint or markedness constraint. Faithfulness and markedness constraint competes with each other, and in one phonological output, only one constraint wins out. The outcome is the winner constraint has more impact on phonological output, the other has less impact. The outcome is an interaction of faithfulness constraint and markedness constraint and its ranking. And it should be noted that it is without exception in that we cannot find that in a situation the outcome, or any phonological output, is made by any constraint that is not defined by faithfulness constraint and markedness constraint. No matter different constraints are formed, they underlies faithfulness constraint or markedness constraint. And this analysis in Optimality theory provides strong explanatory power to wide range of different phonological phenomena. And we expect that this analysis can also combine morphological properties, like rules sensitive to morphological properties mentioned in the front. We assume that morphological motivated phonological output is also governed by faithfulness constraint or markedness constraint. And this is the point we would examine in this paper. Or we need additional force in order to satisfy our need, which is an idea we also have to consider. The issue of morphology and phonology interaction has attracted much attention from phonologists. The theory called Prosodic Morphology is a theory concerning this issue (see McCarthy and Prince 1999). And later Generalized Template Theory is proposed with a goal to reach more explanatory adequacy. The concern about reaching more explanatory adequacy is worth noting in that it eliminates the templatic categories. The constraint like “ Minimal word” with a regard to template or morphological structure is abandoned in Generalized Template Theory, instead using no specific constraint governing templatic structure and different constraints relating to different positions in a template and the ranking between these constraints also make the template structure explicit. For example, we can use alignment constraint to have segments in particular position. And the constraint like this also corresponds to the structure of foot level and also other structure, like prosodic structure. And it should also be noted that the operation of constraint is on the process of parsing and mapping. In this case, the morphological form can be retained in the parsing by faithfulness constraint or will be changed in the parsing due to the markedness constraint a particular language have. This is also a practice of faithfulness and markedness constraint. But this leaves a question that is since the parsing is a process selecting optimal phonological output; it does not have any connection with morphological properties. And if we consider the markedness constraint happening after a morphological output, and it does not have the ability to discern morphological properties, the morphological properties or morphological contrast will be lost in an effect of markedness constraint. And the output will not show morphological properties once have, that is some morphological contrasts will be lost. But this is not the case, the morphological process will be shown clearly in the phonological output, for example the reduplicated form and suffixation, if the output marks no clear morphological process, we will no longer to distinguish a contrast and have different usages. So in this paper we start with morphological theory, considering its morphological motivation. And its motivation cannot be reduced in the process of constraint operation and how this motivation retained in the framework of Optimality Theory. We narrow our scope to reduplication. And we focus our investigation to Hakka reduplication. In this study, we hope that we will find the way morphological motivation can be settled down adequately in Optimality theory. We assumed that this is also a situation of Faithfulness and Markedness interaction. But we also do not exclude other possibilities. Chapter Two Literature Review In this chapter, we first start with the review of morphological theory. Morphology theory offers us with the explanation of the nature of reduplication. It would be beneficial for us to know the underlying motivation of reduplication. And the motivation, in our consideration, has to interact with phonological rules, and then it leads to the output. In OT’s view, we come up with a standard view to explain this process. That is we can say that the morphological motivation is governed by faithfulness constraint. And these motivations have to compete with markedness constraint. Markedness constraint involves any specific phonological requirement in this language. Then in most cases markedness constraint will be ranked above the faithfulness constraint. However, in reality, this view poses some problems. This simplified view seems not to account for all the facts because the situations in different languages are complex. In the literature, there are different constraint rankings in different situations. This is the most interesting part of this study, and we are eager to propose a plausible explanation to account for this. We start with the morphological consideration in view of reduplication. 2.1 Aronoff and Fudeman’s work In Aronoff anf Fudeman’s work, they point out that morphemes are often defined as the smallest linguistic pieces with grammatical functions, and a morpheme may consist of a word, or a meaningful piece of a word. Another way to define morphemes is to say that morphemes are pairings between sound and meaning. In our view, the second definition is to phonologist’s concern. In phonology, the assumption is that there is a linking process between these sounds. But it’s not clear that phonology involves a consideration of the pairing between sound and meaning. It may be natural to say that phonology is all about the consideration of the sounds interaction in a word. In Mccarthy’s (1982) work, the linking of the sounds is toward a template consisting of consonant and vowel. This arrangement is plausible in that it captures the universal characteristic- consonant and vowel form a syllable. The sounds combination is based on a consideration to combine with a vowel and a consonant. But there is a problem that is the original linkage between sound and meaning is broken if we consider a linkage only to CV template. That is we have no specification to affixation and base form. In OT’s view, the form with affixation and base form are all considered as input. And it goes through constraint competition and form an output. There are different outputs between the affixated form and base form. We argue here is that is this plausible for us to say that the similarity between the two outputs indicates the two forms are related. Only through the competition of constraint, then we can find that the similarity of the two forms. In this way, the indication of grammatical function or meaning happens after the competition of constraints and we have to say that the relevant constraint rankings ensure the indication of grammatical function or meaning. In some cases, this idea seems reasonable. For example, the allomorph of English morpheme-‘a’ is ‘an’, and this allomorph is conditioned by its environment to be assimilated. In this stance, we can say the occurrence of ‘a’ or ‘an’ is conditioned by the constraint ranking. The occurrence of ‘an’ can be regarded as the outcome of the dominance of markedness constraint. However, if we also consider the occurrence of the ‘a’, there is a problem we have to consider. The problem is that how can we get ‘a’ from the relevant constraint ranking instead of other sounds? If we adopt the view above that the indication of grammatical from or meaning, maybe the way to combine indication of meaning is absurd, we consider only the indication of grammatical function, then it is the constraint ranking that derives the output ’a’. Therefore, we can consider also another possibility. If we consider ‘a’ is actually specified in the input, then we don’t have to counter this difficulty. In other words, in the input section, there are not only sounds. Instead, there is also a separation of base form and grammatical function form. The settlement here breaks the assumption above that the paring between sounds is only recognized in the phonology. In OT’s literature, we find that the input of reduplication is specified as the RED part and the base form part. However, this is the central idea of Correspondence Theory. The RED part is derived through the constraint ranking copying from the base. But is there the same situation if we consider the ‘a’ morpheme. The problem is that how can we use the relevant constraint ranking to guarantee the derivation of ‘a’? The ‘a’ is believed not to be an instance of reduplication. We cannot copy one sound from the base form then get the ‘a’ morpheme. The ‘a’ morpheme seems to us is abstract, we cannot say that it is derived through constraint ranking. We have to the possibility that ‘a’ is identified as a marker in the input already then along with the base form to have the constraint ranking. Then the ‘a’ remains faithful in the output. Is this proposal plausible? The proposal part we will discuss in the later paragraph. Now, we return to the Aronoff and Fudeman’s work and see more of morphological consideration of reduplication. In Aronoff and Fudeman’s work, they hold that morphology is distinct component in the grammar. The morphology specification cannot be simply accounted for by phonological rules. This view also draws our concern. In our view, when we face the problem like the ‘a’ morpheme, we come up with another idea. We imagine that is there a possibility that ‘a’ morpheme has to be intact in the process of input-output derivation. We consider that it would be reasonable if we consider the morphological motivation of ‘a’ morpheme. The morphological motivation is for ‘a’ to specify the grammatical function. In order to specify the grammatical function, it needs the incorporation of phonological constraint to make the morpheme intact, untouchable. If it undergoes some change due to the influence of markedness constraint, the function to indicate grammatical function is deprived. This is our prime idea. We know that the relevant discussions may be in the literature of OT, and there are also some perfect solutions. We will find the relevant literature to reach further explanation. There are also some morphological motivations that draw our attention, but we will not discuss all these here. We here posit our findings form the literature we find about the discussion of various languages. Reduplication can be regarded as an independent process in some languages, and it can also be taken as affixation in some languages. Actually, in Aronoff and Fudeman’s work, there is no need to make a clear distinction of the replication form. In the concern of morphology, there are only affixation and derivation. The difference between them is one to specify meaning, and one to specify the grammatical function. As for reduplication, it can be taken as either of one kind, depending on the context it is used to specify meaning or function. We find that the reasons to take reduplication as affixation or not in different languages are vary. We do not go on explicate here. But is we adopt the view of morphology, and then there is no need to specify reduplication. According to this view, in the OT’s analysis, the specification of RED in input is actually out of phonological consideration. The specification is actually a linkage of different sound combination between the base form and reduplicated form. 2.2 Alderete et al. ‘s work In Alderete et al ‘s work, we find that reduplicated morpheme in some cases is invariant and not through copying. This finding appeals to us in that reduplication does not result from base form regularly. In the most stances, we have to construct the relation of reduplicated form and the base form, and we convince that the reduplicated form is the reflex of base form. The idea used in Alderete et al. ‘s work is a notion called Emergence of the Unmarked. In our concern, Emergence of the Unmarked explains more than reduplication. Emergence of Unmarked can be used to explain the relationship between the meaning and function pairing. If we consider the ‘a’ morpheme example, Emergence of the Unmarked can help us to explain the derivation of ‘a’ in the constraint ranking. The ‘a’ morpheme actually consists of one sound- schwa. We consider the situation can be explained by the constraint ranking. But we do not go on this discussion here. If reduplication is actually a follow of Emergence of the Unmarked, we have to consider the possibility of using the TETU in most cases. However, in this way, the morphological motivation seems not to be in focus and further erased. 2.3 Tseng’s work Tseng’s work is a discussion of Hakka reduplication. We use this study as an example to further discover the relationship of the morphology and phonology. We consider how to adopt the morphological motivation into the constraint ranking. Tseng’s work is also an analysis of Hakka reduplication, and with reasonable constraint ranking in the framework of Optimality Theory. We first consider the morphological relationship in Hakka reduplication and consider the possibility to add additional component into Tseng’s work. If there is anything we can add into Tseng’s analysis, we examine the morphological consideration in Tseng’s analysis. We first introduce Tseng’s description of the reduplication in the analysis. Tseng’s paper discusses the grammatical operation in Hakka in which a verb is followed by a complement clause heading by a morpheme do, the verb must be reduplicated. For example: (the examples are extracted from Tseng’s work) (1) Gi sii He eat shui-go [do dong fruit really fast Comp kiak]. Reduplicated form: (2) Gi He sii eat shui-go sii fruit eat [do dong kiak]. Comp really fast ‘He ate fruit really fast’ This syntactic operation of verb copying is obligatory in Hakka. And the position of this kind of verb reduplication is rigid. For example :( the data here is also extracted from Tseng’s study) (3) * Gi sii sii [do dong kiak] . This finding draws our attention in that this process is out of a consideration of morphological requirement or phonological requirement. In Tseng’s analysis, the reason is attributed to Obligatory Contour Principle. In that, the reason Tseng conclude will be a phonological motivation. We first look at Tseng’s relevant constraint ranking and propose our thoughts. Tseng’s constraints are listed as following: (4) ABUT (do L, WORD R): attaching the left edge of do to the right edge of the right edge of its preceding word. ABUT (do L, PRED R): attaching the left edge of do to the right edge of main predicate. Uniformity: disallowing the many-to –one correspondences between syntactic nodes and phonological word (i.e. against fusion) Tseng’s ranking is listed as following: gi zeu [ngip vuk] [do dong gip] he run PREP house COMP really hurried ‘He ran into house hurriedly’ ABUT ABUT (WORD) (PRED) a. Gi zeu [ngip vuk ]=do dong gip b. Gi zeu=do [ngip vuk] dong gip c. Gi zeu [ngip vuk] zeu=do dong gip *! *! Uniform * * * In Tseng’s analysis, Tseng does not depict clearly the occurrence of the reduplicated form. Alternatively, Tseng consider the position of the grammatical morpheme-do and use the relevant position of morpheme-do to influence the representation. In this way, the reduplicated verb occurs by satisfying the position requirement of morpheme-do. Tseng’s analysis here involves the morpheme-do’s distinction of word and predicate. In fact, Tseng’s analysis is based on the syntactic view. We do not deny the possibility of a morpheme to recognize some syntactic property, as Lin (1994) describe in the study. But actually according to the generalized templatic constraint, the constraint specified for a certain linguistic unit is not suggested. Moreover, in terms of OCP principle, we consider the principle is mainly used in the avoidance of the combination of certain sounds. We do not see a high potential for the avoidance of the base form and the reduplicated form. We consider the position of the grammatical morpheme-do can be explained by the faithfulness constraint. As for the reduplicated form and the position, we propose the following constraint ranking: gi zeu [ngip vuk] dong gip] [do Parse-prosodic Iden-IO(position) Max-IO word he run PREP house COMP really hurried ‘He ran into house hurriedly’ c. Gi zeu [ngip vuk ]=do dong gip d. Gi zeu=do [ngip vuk] dong gip *! * c. Gi zeu [ngip vuk] zeu=do dong gip * According to this, we can get the correct surface form. We can say that the Parse-prosodic constraint is the motivation of the occurrence of the reduplicated form. This is the markedness constraint in Hakka have to follow. The complement without a verb when preceding a verb and complement cannot be a prosodic word. This constraint outranks the faithfulness constraint and leads to the output. Chapter Three Conclusion 3.1 conclusions In this study, we focus on the relationship of morphology and phonology. We consider possibilities to deal with the relationship in the OT framework nicely. However, we do not find the unified account in this study. We concentrate the reduplication of Hakka and observe the process of the relationship to achieve in the OT’s framework. We hope that this will increase the insights of the interface of morphology and phonology. Chapter Four Reference Alderete, John, Beckman, Jill, Benua, Laura, Gnanadesikan, Amalia, Mccarhty, John, Urbanczyk. 1999. Reduplication with fixed segmentism. Linguistic Inquiry 30. 327-364. Aronoff, Mark, and Fudeman, Kristen. 2005. What is morphology. Oxford. Blakewell. Tseng Yu-Ching. 2008. An OT analysis on verb reduplication in Hakka. Concertric: Studies in Linguistics 34. 53-80.