APA paper_22Nov_final - International Coalition for the

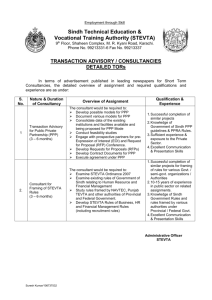

advertisement

The Responsibility to Protect: Guidelines for the International Community to Prevent and React to Genocide and Mass Atrocities Nicole Deller and Sapna Chhatpar, World Federalist Movement-Institute for Global Policy November 2006 Despite the preambular goal of the United Nations Charter to “save succeeding generations from the scourge of war,”1 the international community has not invested in collective mechanisms that would prevent conflict and has not made protecting civilians (particularly in the poorest countries) a political priority. The major powers have consistently failed to take early action in cases where large numbers of civilian lives are in jeopardy. The repeated failure of the international community to react when a country’s populations risk mass violence arises from a lack of will to invest resources in protecting the security of people, combined with a traditional view that principles of sovereignty and non-interference should shield a country from international scrutiny of its internal conduct. The tension between national sovereignty and a lack of international will to protect vulnerable populations was one of the major dilemmas that the international community sought to address at the time of the United Nations’ sixtieth anniversary. At that time, in a UN Summit Outcome Document, governments agreed that there is a national and international “responsibility to protect” populations from genocide, war crimes, crimes against humanity, and ethnic cleansing.2 The significance of the commitment to the responsibility to protect (also referred to as R2P) is that (1) it reconciles the needs and rights of the individual with the duties of the international community and the rights of the sovereign state, reinforcing human security as a priority; (2) it establishes a basis for accountability not only for the state’s failures but also for those of the international community; and (3) it codifies the responsibility of the international community to prevent as well as to react to massive violations of human rights. This paper introduces the principle of the “responsibility to protect” populations from genocide and other mass atrocities as it was initially brought into the international debate and was ultimately accepted by the United Nations. We also discuss its relevance in Southeast Asia and the ways in which it might be taken forward by civil society in Southeast Asia. The International Commission on Intervention and State Sovereignty: Introducing the responsibility to protect The term “responsibility to protect” was introduced in the 2001 report of the Canadian-supported International Commission on Intervention and State Sovereignty (ICISS), entitled The Responsibility to Protect. ICISS was formed to address the questions of when sovereignty must yield to protection against the most egregious violations against humanity and international law— genocide, ethnic cleansing, and massive human rights abuses. Secretary-General Kofi Annan presented this issue as follows: “if humanitarian intervention is, indeed, an unacceptable assault on sovereignty, how should we respond to a Rwanda, to a Srebrenica – to gross and systematic 1 Charter of the United Nations, Preamble. United Nations, General Assembly, 2005 World Summit Outcome, 31, par. 138, 139, (15 September 2005), 2 violations of human rights that offend every precept of our common humanity?3 “ After consultations in every region, ICISS made five principal findings to advance this debate: First, ICISS expanded the view of “sovereignty as responsibility”, meaning that a state has responsibilities along with its rights, principally for the protection of its citizens. Second, if the state in question is unable or unwilling to protect its citizens from mass atrocities, then there is an international responsibility to protect these civilians. Third, the ICISS report explains that the international responsibility is for a continuum of actions from prevention to reaction and rebuilding. Not only should the international community try and stop the atrocities as they occur, but also work to prevent it from happening in the future and commit to help rebuild after a conflict has ended. Fourth, the ICISS report places limitations on when the international community can and should act. This is to avoid improper interventions motivated from states own national interest rather than human protection. Specifically, the ICISS report proposed precautionary principles that would need to be considered if preventive efforts failed and military force was needed. The recommended precautionary principles are: right intention (halting or averting human suffering), last resort, proportional means and reasonable prospects of success. These criteria could serve as indicators for when the Security Council should intervene, and when an intervention is not justified to protect populations. Finally, ICISS discusses the issue of what should be done if the majority of the international community seeks action but the Security Council fails to act. The goal of R2P is to get the Security Council to work better, but if it fails to act to avert mass suffering, ICISS believes alternative sources of authority must be explored, including through the General Assembly or by a regional or sub-regional organization. The timing of the report’s release in 2001 was devastating to its initial reception. After the September 11, 2001 terrorist attacks, debates about preventing future Rwandas were replaced with consideration of measures for prevention and preemption of terrorist activities. The invasion of Iraq, premised in part on an argument of human protection, was even more destructive to the R2P agenda, adding to concern that R2P would be used to advance imperialist motives at the expense of less powerful countries. In this political climate, civil society organizations also began consideration of R2P principles. Consultations among civil society organizations reflected widespread support among NGOs for advancing the idea of sovereignty as responsibility. However, the NGOs consulted showed little interest in the advocacy of a doctrine geared at justifying military interventions, particularly those that occur without Security Council or multilateral approval. 4 Although support for R2P was limited following the release of the ICISS report, ongoing humanitarian disasters, including the crisis in Darfur, signaled that more needed to be done by the international community to respond to genocide and other massive threats against populations. How the responsibility to protect developed as an international commitment In September 2003, the Secretary-General called for Member States to strengthen the UN to better advance development, security, and the protection of human rights. In recognition of the Kofi Annan, “We the Peoples: The Role of the UN in the 21 st Century,” United Nations Department of Public Information (2000), p. 48. 4 See World Federalist Movement-Institute for Global Policy, “Civil Society Perspectives on the Responsibility to Protect,” (April 2003), Link available at: http://www.responsibilitytoprotect.org/ 3 urgent need to address the UN’s failures to respond to genocide, the Secretary-General challenged Member States to include protection from genocide as part of this UN reform agenda. The Secretary-General then formed the High-level Panel on Threats, Challenges and Change to report on how the UN should confront the greatest security threats of the 21st century. In December, 2004, the High-level Panel released its report, A More Secure World: Our Shared Responsibility. Included in the report’s 101 recommendations on strengthening the international security framework was an endorsement of an international responsibility to protect populations from grave threats. The report affirmed that with sovereignty comes responsibility; declared an international responsibility to protect which spans a continuum of prevention, response to violence, and rebuilding and set out a threshold. Secretary-General followed with his own report entitled In larger freedom: towards development, security and human rights for all. Similar to the High-level Panel, the Secretary-General emphasized the need of governments to take action against threats of large scale acts of violence against civilians. The Secretary-General called on governments to embrace the responsibility to protect, emphasizing that while it is first and foremost the individual government’s responsibility to protect its populations, the responsibility shifts to the international community when the state is unable or unwilling to protect. He also emphasized that the international community must use a range of measures to protect populations, which could include diplomatic and humanitarian efforts and may include military force, if required. The early efforts to advance R2P very much emphasized that this was a concept about whether the international community could use force in a country, without its consent, when the country wasn’t protecting its populations. The Secretary-General and key governments from the global south shifted the focus away from a debate about use of force and toward a normative and moral undertaking described by several delegations as “I am my brother’s keeper.” This included a spectrum of activities for the protection of populations, emphasizing the need for the international community to strengthen preventive responses and peaceful measures, with use of force as a last resort. Indeed, the Summit Outcome Document endorsed this framework. World leaders agreed to the following: That each individual state has the responsibility to protect its populations from genocide, war crimes, crimes against humanity and ethnic cleansing. And it is also a responsibility for prevention of these crimes. That the international community should encourage states to exercise this responsibility, including by supporting the creation at the UN of an early warning capability. That the international community, through the United Nations, also has the responsibility to use appropriate diplomatic, humanitarian and other peaceful means to help protect populations from genocide, war crimes, ethnic cleansing and crimes against humanity. That if national authorities manifestly fail to protect their populations and peaceful means are inadequate, the international community is prepared to take collective action through the Security Council, which may mean sanctions or authorization of military force. The Council should act in cooperation with regional organizations as appropriate.5 This outcome has been welcomed by many governments and civil society organizations as a vital new tool to hold governments and the international community accountable when they are 5 United Nations, General Assembly, 2005 World Summit Outcome, 31, par. 138, 139, (15 September 2005), manifestly failing to respond to grave threats to humanity. In recent remarks on the accomplishments of the past decade, Kofi Annan listed the acknowledgement by states of a responsibility to protect as one of the big steps that the UN has taken “in the common struggle for development, security and human rights.”6 The responsibility to protect within Southeast Asia The fact that the responsibility to protect is now an international commitment has not received much exposure in the broader international discourse. For R2P principles to gain wider acceptance, they must be understood as relevant to the work of policymakers and advocates dedicated to advancing issues of human security. This section discusses some of the ways in which actors in Southeast Asia can engage on the issues presented by the responsibility to protect. Does R2P apply to conflicts in Southeast Asia? One way in which governmental and non-governmental actors can relate to this issue is by considering whether there are currently any situations in the region that meet the high threshold of crimes under which R2P would apply—meaning war crimes, genocide, crimes against humanity and ethnic cleansing. Furthermore, can lessons be learned from the international failures to prevent large scale loss of life in prior conflicts such as the killings in Cambodia in the 1970s or the war crimes and crimes against humanity committed against the people of East Timor by Indonesian armed forces in the 1990s. Some have argued that the responsibility to protect may again apply today in Burma, with the widespread and systematic rape of ethnic women by the Burmese military, destruction of thousands of villages, and the torture and imprisonment of the political opposition. As R2P involves not only reaction to existing crises but prevention of future atrocities, it is also relevant to consider where lower-level conflicts may place populations at risk of mass suffering, and whether there are regional or international measures that should be adopted to prevent the conflicts from escalating. Resolving questions of sovereignty and human security Traditional conceptions of sovereignty and respect for territorial integrity remain strong within this region and throughout the world.7 Although many states support a “flexible” approach to the concept of non-interference, are ASEAN countries prepared to support measures for humanitarian protection up to and including the use of force? 8 The question posed by Kofi Annan of how to resolve the concept of sovereignty with human protection remains unsettled for many regions. According to Dr. Morada of the Institute for Strategic and Development Studies, there are many scholars, think tanks, and NGOs in the region who have begun to prioritize the need to protect people in humanitarian crises over the strict adherence to sovereignty.9 As for governments, the statements by ASEAN members leading to the UN summit affirmation on the Responsibility to Protect are instructive. “In final UN Day message, Annan warns that much still needs to be done,” UN News, (23 October 2006). Paul M. Evans, “Human Security and East Asia: In the Beginning,” Journal of East Asian Studies 4 (2004), p. 269. 8 Governments in Southeast Asia spoken out about a variety of “internal” affairs in recent years, such as the conflict in East Timor, violence in southern Thailand, and human rights abuses in Burma which ASEAN governments discouraged Burma from chairing the body in 2006. 9 Noel M. Morada, “R2P Roadmap in Southeast Asia: Challenges and Prospects,” UNISCI Discussion Papers 11 (May 2006), p. 63. 6 7 Malaysia’s primary concern with R2P is that an R2P argument may be used by some of the major powers as a motive to intervene in Third World countries for the purpose of self-interest, and not on purely humanitarian grounds. For this reason, Malaysia advocates intervention only with full consensus of the United Nations.10 The Foreign Minister commented that “actions must be in accordance with the respect for the sovereignty and territorial integrity of states as well as observing the principle of non-interference.”11 Since that time, Malaysia has voiced support for interventions for humanitarian purposes. A July 2006 statement given by Malaysia’s Foreign Minister Datuk Seri Syed Hamid Albar, indicated that Malaysia had made the decision to send troops to Cambodia, Congo, Somalia, Bosnia-Herzegovina and in Timor Leste primarily for the purpose of human protection.12 He said that, "This is an example of the concrete type of intervention that helps to protect the life of countless ordinary people and communities.” Singapore’s pre-summit statements also reflected an evolved understanding of sovereignty. On 7 April 2005, Permanent Representative of Singapore to the UN Vanu Gopala Menon said, “…it is high time that massive killings and crimes against humanity be things of the past. Yet, these things continue to happen, and they continue to be protected by walls of an antiquated notion of absolute sovereignty.”13 He stressed the need for the General Assembly to establish criteria on how to prevent and deal with these crimes, so that there would be no abuse by states when force was needed. On 19 April 2005, the Ambassador challenged the General Assembly to establish these rules, and stressed that if the GA was unable to conceive of such criteria, then the Security Council should be empowered to do so.14 Discussions among Southeast Asian governments and civil society are part of the larger debate taking shape in other parts of the world, and show an evolution of the concept of sovereignty that is consistent with R2P principles. Yet a reluctance to apply the principle to actual situations of human suffering remains. In Africa, the responsibility to protect is enshrined in the African Union’s Constitutive Act15 yet many African governments resist applying these principles to protect civilians at risk in situations such as Uganda or Zimbabwe. Members of the Security Council “reaffirmed” the World Summit Outcome document’s statement on R2P and invoked R2P in a resolution on the situation in Darfur.16 The Security Council, however, has not implemented many of the measures that is has adopted to respond to this crisis and the decision to deploy UN peacekeepers is subject to the consent of the Sudanese government.17 A recent New York Times Magazine interview with China’s Ambassador to the UN revealed the extent to which the role of sovereignty and R2P in Darfur has yet to be resolved: Dennis Ignatius, High Commissioner of Malaysia, “The Responsibility to Protect - a Third World Perspective,” Embassy: Canada’s Foreign Policy Newsweekly (24 August 2005), Link available at: http://www.embassymag.ca/html/index.php?display=story&full_path=/2005/august/24/r2p/. 11 “M'sia Recognises Need To Intercede On Humanitarian Grounds,” Bernama News (13 June, 2006), Link available at: http://www.bernama.com.my/bernama/v3/news.php?id=203052. 12 “M'sia Recognises Need To Intercede On Humanitarian Grounds,” Bernama News (13 June, 2006), Link available at: http://www.bernama.com.my/bernama/v3/news.php?id=203052. 13 Vanu Gopala Menon, Permanent Representative of Singapore to the United Nations”, 87 th Plenary Meeting on the Report of the Sec-Gen “In Larger Freedom: Toward Development, Security and Human Rights for All,” (7 April 2005). 14 Vanu Gopala Menon, Permanent Representative of Singapore to the United Nations”, Informal Thematic Consultations of the General Assembly to Discuss the Four Clusters Contained in the Secretary-General’s Report “In Larger Freedom: Toward Development, Security and Human Rights for All,” (7 April 2005). 15 African Union, “Constitutive Act of the African Union”, Article 4, (11 July 2000). 16 United Nations Document S/RES/1674 (2006) and United Nations Document S/RES/1706 (2006). 17 United Nations Document S/RES/1706 (2006). 10 In another conversation. . . the ambassador insisted that the right to exercise sovereignty free from outside interference was enshrined in international law. But, I asked, when the world's heads of state, gathered at the U.N.'s 60th-anniversary summit last September, approved the principle of ''the responsibility to protect,'' didn't this, too, become a matter of international law? This was true, Wang conceded -- even though China has strong reservations about the doctrine -- ''but you have to decide how to apply this.'' And since this new obligation applied only to genocide or ''massive systematic violations of human rights,'' it had no bearing on Darfur. 18 Without strong support for putting the responsibility to protect into practice, this may become a standard reaction to the R2P commitment. Governments may begrudgingly admit that such a commitment exists, only to resist any application to specific conflicts. Support within ASEAN countries for the broader spectrum of R2P measures One way to avoid devaluing the R2P principles is to emphasize the importance of non-military responses to fulfill the responsibility to protect. R2P is a continuum of actions ranging from assisting host governments to addressing internal situations, to application of pressure through sanctions and moral suasion, to military intervention as a last resort. While ASEAN countries are understandably cautious about yielding sovereignty for military intervention, would they be willing to call for a non-military R2P response to mass crimes? Civil society in Southeast Asia can advance this debate by identifying measures short of force that the UN, governments, and ASEAN should apply in situations of mass violence against a country’s populations. Similarly, it is also necessary to recall that the R2P definition as originally articulated in the ICISS report and later affirmed in the 2005 World Summit outcome document outlined a continuum of international responses to mass threats, ranging from prevention to reaction and then to rebuilding. Apart from the question of military intervention, R2P can be still relevant in Southeast Asia in the areas of prevention and rebuilding. As Dr. Morada wrote in his report entitled, “R2P Roadmap in Southeast Asia: Challenges and Prospects,” there is a need to identify how governments and civil society in Southeast Asia understand the norm and use it to increase their capacity for conflict prevention, response, and management.19 Placing R2P within existing peace and security frameworks R2P might best be understood within the context of the human security framework. R2P is rooted in the concept of human security because it emphasizes the duty of the state and the international community to prioritize the security of the individual. The inclusion of a broader human security agenda within the ASEAN Charter is already underway by civil society. The Solidarity for Asian People’s Advocacy (SAPA) submission to the Eminent Persons Group on the ASEAN Charter included the following clause: “The ASEAN Charter should define clearly that the responsibilities of the state to protect, promote and fulfill its obligations in respecting the rights of its citizens supersede the obligations it imposes on its citizens.”20 Ensuring the capacity and will to implement R2P should be part of a comprehensive strategy to promote human security, including through the advancement of democracy, protection Jim Traub, “The World According to China,” NY Times Magzine, (3 September 2006). Noel M. Morada, “R2P Roadmap in Southeast Asia: Challenges and Prospects,” UNISCI Discussion Papers 11 (May 2006), p. 66. 20 Solidarity for Asian People’s Advocacy (SAPA), “Submission to the Eminent Persons Group on the ASEAN Charter,” Ubud, Bali (17 April 2006). 18 19 of human rights, good governance and economic stability. The R2P concept should also be viewed in the context of the intergovernmental commitments to the protection of women’s human rights and security, such as the Beijing Platform for Action and Security Council Resolution 1325 on women, peace and security. It is important for civil society advocates of women’s rights to be involved in discussions of how R2P will be implemented. This includes using gender-specific indicators to determine which crises require regional and international responses, and ensuring that responses to humanitarian crises take into account their impact on women. Conclusion: In many regions, civil society organizations working on issues of human rights, peace and security, women’s rights and children’s rights are beginning to consider how their work might be advanced by a broader acceptance of an international responsibility to protect. They are also considering how to engage with their governments, regional organizations and international organizations on how to develop a system of prevention and reaction to mass atrocities. Civil Society organizations in Southeast Asia are strongly encouraged to become involved in these discussions. They can begin by asking: What are the main questions or concerns for your NGO and community about R2P? Can you identify the types of crises where your NGO would consider that the international community should take measures for the protection of populations? What measures short of force should NGOs ask the UN, governments and regional organizations to apply? If measures short of force are not sufficient to prevent genocide, ethnic cleansing or similarly large scale human rights violations, would your organization consider calling for military action through the UN? Through regional organizations? Does your organization support the adoption by governments of formal criteria to guide the question of military intervention (that is, should governments be required to satisfy an analysis that the intervention is for the right intention, last resort, will use proportional means and carry a reasonable prospect of success)? Is there a crisis going on now where the responsibility to protect should apply? When possible, civil society should engage government officials working on issues of human rights, protection of civilians in armed conflict, peacebuilding, and peacekeeping through letters, panel discussions, briefings and dialogues. Consider raising the following questions: Are officials aware of the commitment to R2P made at the UN Summit? Does the official/parliamentarian hold reservations about the R2P doctrine? Is your government taking steps to incorporate the responsibility to protect into its doctrines and strategies? What strategies and mechanisms are in place within your government for the prevention of armed conflict? Does your government have a mechanism to interact with civil society on these issues? Finally, in order to gain greater support within governments for the protection and prevention of populations from mass atrocities, civil society could seek for the ASEAN Charter to recognize the 2005 World Summit Outcome document and endorse the responsibility to protect.