King Robert the Bruce 1274-1329 - Blog Franco

advertisement

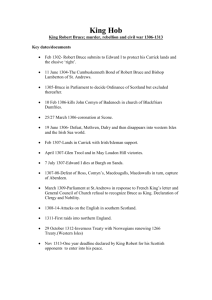

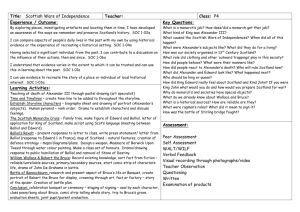

King Robert the Bruce 1274-1329 Where did the family Bruce originate? Addressing the question of whether a Robert of Brix accompanied William on his conquest of England. To find a list of the names of the noblemen of Normandy who accompanied William the Conqueror in 1066, look to contemporary writers to find a credible account. For example, Guillaume Caillon, monk from Jumièges who, although not part of the ducal expedition of William the Conqueror, was considered a notable witness of events from the point of view of the Norman people of his time, especially his writing regarding the succession of Edward the Confessor and the conquest of England. The most well-known chronicler of the time was Robert Wace who wrote 'Le Roman de Roi' a history of the dukes of Normandy since Rollon a Norwegian who became the first duke of Normandy in 911. However, Wace lived one hundred years after the conquest of England. His work was written between 1160 and 1170. Born on Jersey, he became a clerc in Caen, then a prébendier in Bayeux. He was a court poet and served to flatter whomever he happened to be serving. Viewed from modern times it is difficult to separate fact from fiction in his writing. The Bayeux tapestry is another source of information of the history of the time. Throughout the ages others have attempted to chronicle the participants and numbers of names vary considerably. Recent lists follow the work of Wace and the Domesday Book, which showed the owners of land in England in 1086, however, that is not proof of a person's presence at the battle of Hastings. Some illustrious families who gained domains on the English side of the channel did not take part in the battle. Roger de Montgommery, for example, cited by Wace to be part of the roll call from Dives sur Mer, the port of departure of William's troops, stayed in Normandy at the head of the council which governed the duchy and he did not go to England until December 1067. There is also confusion with the name Briouze, an entirely different family who came from Argentan area and held important lands in the South of England. So, did a noble from Brix take part in the conquest of England? Wace lists: Brius, Brompton: Brus, Leland: Bruys, Holinshed: Brutz, Scriven: Brus. Note, no Brix. Modern lists from the Roll of Falaise and Dives give the actual name and the parish of origin: Brix and the prénom Robert. The first mention then of Robert of Brix dates from a record written a whole century after the event, that is to say that the presence of a member of the Bruce family on the conquest of England leading to the Battle of Hastings in 1066, appears from that time to have been possible but not certain. What does appear more certain is that there is a link between the Bruce family and the village of Brix, situated between Cherbourg and Valognes, of which the name has been changed over the centuries. Various accounts of ancient history cite that the hill of Brix was inhabited at the time of the conquest and that the Romans established a villa there, a small centre of administration. The oldest document to mention the village of Brix still in existence dates from 747 and refers to the relics of Saint George being transported from Portbail to a hill at Brix where flowed the river Undwa (l'Ouve). Mention is made of the village of Brutius, which belonged to a powerful man named Benehardus. He built a church in honour of St. George. Brix, situated on the banks of the D'ouve was called Brutius before the Scandinavian invasion and its lord took his surname from that Roman word. It is probable that the church of St George built on the hill of Brix was destroyed in the 9th Century by the Vikings, as were most of the sanctuaries of the Contentin and that the village of Brix was also ravaged by them. We hear no more of Brix until the year 1000 when Richard II had the domain of Brix, then named Bruet, in the dowry of his fiancée Judith of Bretagne. So there was a chateau at Brix, probably a simple tower or donjon in wood above a motte (earth mound). Castles in stone did not appear until the 11th century. The establishment of the first lord of Brix is placed between 1030 and 1035, headed by Duke Robert. It is probable that his family originated in Scandinavia and from that time the lands of the family Brus became ever more important and in high favour, whether through blood ties or for services rendered or both. Many Scottish clans and family names have their roots in Normandy. This area of northern France was colonised by land hungry Vikings in the early 10th century. The name Normandy means Home of the Northmen. Their leader, Rollo the Viking, signed a treaty with King Charles the Simple of France in 911 which gave the Norsemen a permanent home on French soil. However, conserved in Edinburgh is a manuscript written by George MacKenzie, lord advocate of Scotland under king Charles II, wherein is a study of the house of Bruce. This commences with Adelme de Bruis, a Norman noble who received the town and castle of Bruis, and who, with other Norman lords in 1050 accompanied Queen Emma to England and remained there with her. Emma was the wife, first of king Ethelred of England and then, on the death of Ethelred she married his vanquisher, king Canute (Knut) in 1017. After her death in 1052, extremely hated by the English, Bruis fled to Scotland where he gained the land of Boulden, either by marriage or gift of the king. Most of the Normans who went with Queen Emma then entered the service of King Macbeth in Scotland. We now have established the family of Bruce in the United Kingdom before the conquest of England by William. Who to believe as chronicler? We must remember that the village of Brix continued to be held by the family named Bruis, albeit that there is a record of a member of that same family recorded in Scotland. Let us leave discussion of the village of Brix and concentrate on the subject of this paper, King Robert the Bruce of Scotland. 2 According to Scottish history, the Bruce family from Brix in Normandy, were in England before William the Conqueror and were granted land in Galloway, southern Scotland, by King David I in the 12th Century. The name of Robert de Brus was seen in England for the first time around 1094. The youngest son of William the Conqueror, Henri, was born in 1068 in Yorkshire. His brother William failed to successfully manage the estates back in Normandy and had to sell to Henri in 1088 for 3000 livres, the 'comte' of Coutances which comprised le Cotentin and L'Avranchin. It is probable that at this time Henri encountered Robert de Brus. Robert went on a crusade to the holy land around the time that Henri became king of England. (Henri de Beauclerc, king of England 1100-1135, Duc de Normandie 1106-1135.) It is practically certain that a Robert de Brus fought on the side of Henri I in 1106 at the battle of Tinchebray and, as a reward, Robert was given the fiefdom of Yorkshire (including Cleveland and Durham). A record of his ownership appeared in the Domesday Book Robert de Brus had been a friend in his youth of King David of Scotland but had to take Anglo-Normand loyalty and during the Battle of the Standard (Northallerton) in 1138 his sons found themselves on opposing sides. When Robert died in 1142 his son Adam inherited his English possessions of Yorkshire and remained 'suzerain' of the baronerie of Brix which was held for him by his cousins. Robert's younger son, Robert of Meschin inherited the fiefdom of Annandale in Scotland through his loyalty to King David. Robert the Bruce was probably born in Turnberry Castle in Ayrshire on 11 July 1274 two years after Edward Plantagenet became King Edward I of England. However, there are alternative claims for the place of his birth, notably, Lochmaben Castle in Annandale, Dumfriesshire, which was the seat of the Bruce family. His grandfather, Robert Bruce of Annandale, a descendant of King Alexander II, had estates in Huntingdon, England, as well as Scotland The struggle for control of Scotland began when Alexander III died in 1286, leaving as heir his grandchild Margaret, the infant daughter of the King of Norway. King Edward of England, with his eye on the complete subjugation of his northern neighbours, suggested that Margaret should marry his son, a desire consummated at a treaty signed and sealed at Birgham. Under the terms, Scotland was to remain a separate and independent kingdom, - 'separate, distinct and free in itself without subjection from the realm of England', although Edward wished to keep English garrisons in a number of Scottish castles. On her way to Scotland, somewhere in the Orkneys, the young Norwegian princess died. The succession was now open to many claimants, the strongest of whom were John Balliol and Robert Bruce. John Balliol was supported by King Edward, who believed him to be the weaker and more compliant of the two Scottish claimants. Balliol was an English baron belonging to a house with an established tradition of loyalty to the English crown. The name 'de Bailleul' is mentioned on both the Falaise roll and also the list from the plaque at the church of Dives which tells us that this family did indeed accompany William to invade England in 1066. At a meeting of 104 auditors, with Edward as 3 judge, the decision went in favour of Balliol, who was duly declared to be the rightful king in November 1292. Robert Bruce, Earl of Carrick, one of the seven Celtic earldoms of Scotland, and his grandson Robert the Bruce, refused support for John Balliol. The English king's plans for a peaceful relationship with Scotland now took a different turn. In exchange for his support, Edward demanded that he should have feudal superiority over Scotland, including homage from Balliol, judicial authority over the Scottish king in any disputes against him by his own subjects and defrayment of costs for the defence of England as well as active support in the war against France. Even the weak Balliol could not stomach these outrageous demands. Showing a hitherto unknown courage, in front of the English king he declared that he was the King of Scotland and should answer only to his own people, refusing to supply military service to Edward. The impetuous man then concluded a treaty with France prior to planning an invasion of England. Edward was ready. He went north to receive homage from a great number of Scottish nobles, as their feudal lord, among them none other than 21 year old Robert Bruce, who owned estates in England. Balliol immediately punished this treachery by seizing Bruce's lands in Scotland and giving them to his brother-in-law John Comeyn. Yet within a few months, the Scottish king was to disappear from the scene. His army was defeated by Edward at Dunbar in April 1296. Soon after, at Brechin, on 10 July, he surrendered his Scottish throne to the English king, who took into his possession the stone of Scone, 'the coronation stone' of the Scottish kings. At a parliament, which he summoned at Berwick, the English king received homage and the oath of fealty from over 2,000 Scots. He seemed secure in Scotland. Flushed with his success, Edward had gone too far. The rising tide of nationalist fervour in the face of the arrival of the English armies north of the boarder created the need for new Scottish leaders. Following a brawl with English soldiers in the market place at Lanark, a young Scottish knight, William Wallace of Paisley, after killing an English sheriff found himself at the head of a fast-spreading movement of national resistance. At Stirling Bridge, a Scottish force led by Wallace won an astonishing victory when it completely annihilated a large, lavishly equipped English army under the command of Surrey, Edward I's viceroy. Yet Wallace's great victory, successful because the English cavalry were unable to manoeuvre the marshy ground and their supporting troops had been trapped on a narrow bridge, proved to be a Pyrrhic one. Bringing a large army north in 1298 and goading Wallace to forgo his successful guerrilla campaign into fighting a second pitched battle, the English king's forces were more successful. At Falkirk, they crushed the over-confident Scottish followers of Wallace. Falkirk was a grievous loss for Wallace who never again found himself in command of a large body of troops. After hiding out for a number of years, he was finally captured in 1305 and brought to London to die a traitor's death. With the execution of Wallace, it was time for Robert the Bruce whose heritage of Carrick made him much more than a 'mere Anglo-Norman fish out of water grassed on a Celtic riverbank' to free himself from his fealty to Edward and lead the fight for Scotland. Robert the Bruce became a convert to the patriotic cause. In the 13th century Scotland and England were good friends before Edward I invaded and declared the country a 4 vassal kingdom in 1296. Anglo-Norman nobles held lands in both countries and Bruce had spent most of the early part of his life in the court of Edward I of England. The period between 1291 and 1328 is described as the Wars of Independence. Wallace' example might well have inspired Bruce to do his duty by Scotland. One must take into consideration the fact that Bruce was only half Norman, his mother being the Celtic Countess of Carrick. Bruce became a Guardian of Scotland with his cousin, John Comyn, Lord Badenoch. When King Edward offered a truce in 1302, Bruce accepted and joined Edward's Scottish Council. In 1304, on the death of his father, the Earl of Carrick, Bruce was reputedly the richest man in England and had ambitions to become king of Scotland. Bruce fought his first action at Methven in 1305 and lost heavily. In 1306 he forced a quarrel with John Comyn, his life rival and Balliol's agent in Scotland. He arranged a secret meeting and murdered him at the altar of Greyfriar's Kirk in Dumfries. This led to him becoming an enemy of King Edward; the Comyn family; and the Church for committing murder in a holy place. King Edward captured Bruce's wife and family and put some of them in cages as a punishment. The Comyns were the main family against Bruce although he had many other lesser enemies. Bruce declared himself King of Scotland. He was crowned at Scone in March 1306. He then began a guerrilla war against the English King Edward I known as the Hammer of the Scots. After a year of demoralisation and widespread English terror let loose in Scotland, during which two of his brothers were killed, Bruce came out of hiding and won his first victory on Palm Sunday 1307. From all over Scotland the clans answered the call and Bruce's forces gathered in strength to fight the English invaders. Edward I was by now an ageing, weak and sick king and it was left to his son Edward II to try to carry out his father's dying wish that Scotland be crushed. However, he was no man for the task and had no wish to get embroiled in the affairs of Scotland. Bruce was left alone to consolidate his gains and to punish those who opposed him. Initially he was not successful, but after wandering in the highlands and islands, gradually, with increasing support, he captured a number of castles, chivalrously allowing the defenders to return to England. In 1309 he was recognised as sole ruler of Scotland by the King of France, and, despite his earlier excommunication, even received the support of the Scottish Church. Thus emboldened, in 1311 Bruce drove out the English garrisons in all their Scottish strongholds except Stirling and invaded northern England. Edward II now had to bestir himself and responded by taking a large army north. On mid-Summer's Day, 24th June 1314, one of the most momentous battles in British history occurred. The armies of Robert the Bruce heavily outnumbered by their English rivals, but employing tactics that prevented the English from effectively employing its strength, won a decisive victory at Bannockburn. Scotland was wrenched from English control, its armies free to invade and harass Northern England. 5 Bruce's staunchest lieutenant was Sir James Douglas, son of Douglas 'Le Hardi'. Know as the Black Douglas, he was a brilliant guerrilla fighter. The second was Thomas Randolph, the Earl of Moray, Bruce's nephew. Both played a key role at Bannockburn in 1314 and their raiding into the north of England was a key factor in bringing Edward III to the negotiating table. Angus Og MacDonald, Lord of the Isles was an early supporter of the Bruce cause. Other included Sir Neil Campbell of Lochawe and Sir Andrew de Moray. Bishop Lamberton, primate of Scotland was also a close supporter. Bruce was a great military leader and Bannockburn was a classic example of applications of the principles of war. He was also a great trainer of men and took great pains to know personally his veteran soldiers and their officers. It is understood he spoke some Gaelic in addition to Latin, Norman-French and the crude Inglis, forerunner to modern English. Modern re-constructions of his face show him to have a very pronounced jaw and strong, noble features. His compassion and sense of humour are also well documented. In 1320 the Scottish nobility signed the Declaration of Arbroath which was sent to the Pope in Rome, pleading the case for a Scotland free of English domination. The declaration was drawn up by Bishop Lamberton and other clergy. It is a long document but its most quoted line may be translated as follows: "for so long as one hundred of us remain alive, we shall never in any wise submit to the domination of the English, for it is not for glory we fight, for riches or for honours, but freedom alone, which no good man loses but with his life". Bruce defeated Edward II's invasion in 1322. Raiding continued against the north of England until 1327. Bruce also fought in Ireland with his brother Edward, who for a time was King of Ireland. In1328, Bruce, by now an old and stricken man witnessed the culmination of a lifetime's work when English King Edward III eventually agreed to sign the Treaty of Edinburgh acknowledging Scotland's independence, ending the 30 years of Wars of Independence. The next five hundred years would see both nations fight one another in more wars but never again would Scotland's very existence be denied. This is Bruce's true legacy. He was the best-loved monarch in all Scotland's long and bloody history. King Robert was gravely ill by this time and died at Cardross on 7 July 1329. His body was buried in Dunfermline Abbey. It had long been Bruce's wish to go on a crusade against the Infidel and, after his death, his heart was taken on a crusade by James Douglas. In a fight against the Moors in Spain, Douglas was killed and the embalmed heart was returned to Scotland by Sir Keith Graham of Gawliston. It was buried in Melrose Abbey. Recently a new casket was created for the embalmed heart. A new stone was placed over the spot where his heart is interred. It is inscribed with the words, in Scots, "A noble hart may hae nae ease, gif freedom failye." "A noble heart may have no ease if freedom fail". Bruce was married two times; in 1296 to Isabella of Mar who died in childbirth, then in 1302 to Elizabeth de Burgh of Ulster from whom there was one male heir, David, who later became David II of Scotland in 1329. His daughter Marjorie married 6 Walter the Steward, whose son later became Robert II of Scotland in 1371, and from this union was the Royal House of Stewart/Stuart descended and the current British royal family. Bruce also had a number of illegitimate children. Legends The legend of Bruce's spider is most famous. After the capture of his wife and children by Edward, when his fortunes were at a low ebb, he spent the winter alone sheltering in a cave on a deserted island. He is reputed to have seen a spider in the cave trying and failing again and again to spin a web. It was eventually successful, encouraging Bruce to continue his campaign against the English. Inspired by the spider's example, Bruce returned to inflict a series of minor defeats on the English which won him fame and brought him more supporters. Then he turned on the Balliols and Comyns and destroyed them because they would not accept him as king. There are also many stories that Bruce may have been a leper. This is untrue, Bruce fathered a number of children late in his life, none of them or his wife ever showed signs of the disease. It is more likely that he had syphilis, the 'disease of kings'. Bruce is also said to have slain Sir Henry de Bohun, the English champion on the first day of the battle of Bannockburn. He faced a heavily armed knight on a light pony and killed him with one blow from his battle-axe. Modern historians strongly dispute that de Bohun ever existed. -----With reference to the family Bruce and liaison with France against England, see article by Martin Collins given to the group studying the 100 Years War; "in 1336, David Bruce, King of Scotland fled to France and, with the king's connivance, collected a fleet and raided Jersey and Guernsey. De Normandie au Thrône d'Ecosse - La saga des Bruce, Claude PITHOIS (Look for same author, Brix, Cerçeau des Rois d'Ecosse, impremerie Charles Corlet, Ave de General de Gaulle, Condé sur Noireau 1980). Kathleen Cameron January 2005, Normandy 7