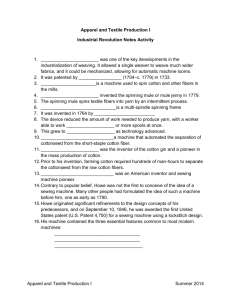

The New Lanark Spinning Mule/ People and Cotton

advertisement

The New Lanark Spinning Mule/ People and Cotton The machine that visitors see and hear in the New Lanark Visitor Centre has been installed as a working exhibit. Built in 1891, it was in production in a woollen mill in Selkirk, in the Scottish Borders for almost 100 years. The Development of the Spinning Mule Spinning was originally done by hand, on drop spindles or domestic spinning wheels. The carded or combed out yarn had to be drawn out, twisted and wound on to a spindle. The invention of spinning machines meant that many strands could be spun at the same time, and a strong, even thread could be produced. The Spinning Jenny was invented by James Hargreaves in 1764, and patented in 1770. The power was provided by the spinner turning a wheel by hand, but a moving bar meant that several threads could be drawn out at once. The Water Frame was patented by Richard Arkwright in 1769. This could be driven by water-power and it could produce strong yarn. This was the type of machine for which the New Lanark mills were built by David Dale, who formed a partnership with Richard Arkwright. In 1785, a team of men and boys were sent from New Lanark to Arkwright’s mill in Cromford, to be trained in their use. The Spinning Mule was invented by Samuel Crompton, and patented in 1779. It was called a mule because it was a cross between a water frame and a spinning jenny. Although he was technically minded, it is believed that Crompton stumbled upon his invention by accident! It was particularly suitable for spinning fine yarns, as the moving carriage, which travelled backwards and forwards along a track on the floor, meant that the threads could be drawn out further. At first the yarn had to be wound on to spindles by hand, but by 1825, the ‘self-acting’ mule had been invented by Richard Roberts, which did this automatically. The New Lanark spinning mule was built by the Platt Company. Although Platt’s mules like the one now working in the Visitor Centre were used to spin cotton in Mill Three during the 19 th century, the New Lanark mills moved with the times, and mule-spinning was gradually superseded by ringspinning. However, this mule is a wonderful example of 19 th century textile engineering, helping to give visitors a realistic impression of a period in the history of the New Lanark mills, which is now beyond living memory. The woollen yarn which is now produced on the mule is available for sale to both retail and wholesale customers. Powering the mule The spinning mule is driven in the traditional way by a system of line-shafting and a belt drive. Originally the horizontal shaft, which turns the belt would have been powered by a water-wheel, down in the basement of the mill. Again as new technology was developed, New Lanark gradually replaced its ten water wheels with three water turbines. The turbine in Mill Three was used to generate hydro-electricity, and the natural energy of the river Clyde was used in a more technologically efficient way. Today the shafting is still driven by hydro-electricity, generated on site using the restored 1930s water-turbine in the basement of Mill Three, making use of the original mill lade excavated by David Dale’s men in 1785. For more information, see the New Lanark Power Trail guide-book available from the Gift Shop or to order on-line at www.newlanark.org The Spinning Process By the time the yarn reaches the mule, it has been teased out and carded or combed out on a set of carding engines on Level Two of the mill. These machines can be viewed through the glass panels to the rear of the Gift Shop. By the end of the carding process the fibres lie parallel as a flat ‘lap’, which is divided into strands. These strands are wound onto condenser bobbins, which are brought up to Level Four and loaded on to the mule. 1 Each bobbin has 28 separate strands or ‘ends’ as they are called. These ends are passed through guides and rollers onto metal spindles at the front. Each spindle has a wooden ‘pirn’ fitted over it, which the ends are wound on to. In all there are 392 spindles. As the carriage rolls out, a controlled amount of yarn is released from the back roll, which then stops, letting the thread be stretched out more finely by the moving carriage. At the same time the spindles turn round, and twist the fibres around each other to strengthen the threads. Once the carriage has moved right out it stops, and the spindles turn even faster, adding a tighter twist. When spinning is complete the carriage moves back in and the spun thread is wound onto the pirn. A full pirn is known as a ‘cop’ and each of the 28 ends will fill more than one cop. Therefore after the first one is full, it has to be ‘doffed’ (taken off) and replaced with an empty prin. It takes about three hours to spin a full ‘cheese’; in other words to spin the full length of yarn held on the bobbin. Bits and Bobbins Piecers- From time to time during spinning, an end will break, and must be joined again. This is called ‘piecing’. It needs nimble fingers and a lot of practice! In earlier times this was a job that was often done by women and young people. Many employers believed that only children who began to learn these skills before they were 12 years old would turn out to be first-class piecers. Spin Statistics – in 1813, there were over 30,000 spindles in operation in the New Lanark Mills, and more than 500 spinners. By this time the mills were producing in one week, enough yarn to go 2 ½ times round the world Speak Up! – The noise of the machinery was deafening. Many workers learned to lip-read or use sign language to communicate with their peers. Scavengers – The machines produced over 24 tons of cotton every week; young children had to crawl under the moving machinery to keep the mule clean of dust and loose threads. This was dangerous work for these children who were known as ‘scavengers’. Mule-spinning in the 1830s – note the child worker sweeping up under the moving machine Wages – In 1885 the working week at New Lanark Mills was 60 hours from Monday to Saturday. The 1885 Wages Records show that piecers working on the Platt’s Spinning Mules in Mill 3 earned an average wage of 11 shillings a week. People and Cotton The People and Cotton Exhibition on the same floor as the spinning mule, shows large projected images and film footage of those who were employed in the cotton industry; including the cotton pickers of the Southern United States, the dockers shipping the cotton and the New Lanark mill ‘hands’. For all involved, it was hard work, as the following New Lanark workers recall (extracts from the New Lanark Oral History Archive): Tom was born in 1906 in Fife, and his family moved to New Lanark village in 1916. In 1922 he started work in the mills where he worked until closure in 1968. He lived with his wife in Caithness Row until the 1990’s. 2 ‘My first job was tying bands in the spinning department. The spinning frame consisted of a long frame with two cylinders underneath and you had a sort of special woven string, and you tied it round one of the cylinders and round the spindle. And when the cylinder revolved, it drove the spindle you see. So my first job was what was called ‘tying bands’ in the spinning department. Later on I was transferred down to the basement of the mill where they cleaned the cotton. That was the first stage of the cotton, it was called the Blowing Department. We opened the bales as they came from Liverpool, it was mostly American cotton. We opened the bales, and we fed it into what was called a bale-breaker. That teased it all up, and then it went through a big ‘opening machine’. It churned all the cotton up and underneath the machine there were ‘mines’, sort of mines, and there were fans, and it sucked all the fine dust through two rollers composed of cages. They were in the shape of rollers, but they were cages, but the dust went through, and was sucked away down into the river. And then from this it (the cotton) carried on and was formed into ‘laps’. Then these laps were fed into another machine called a ‘finisher’ and they were finished there. Each lap weighed about 44 lbs. And the sheets had to be pretty level. If you got a thick bit and then a thin bit, for instance, that carried on through the whole process, and you got faulty yarn. You didn’t get an even yarn. This lap had to be kept fairly even. And from there it went to the carding department where it was carded. Although we took the most of the dust and everything away, there was still more to come. And that was taken out in the carding department, and all the very short fibres were taken out there, and only the best long fibres were left. From there it went to what they called ‘draw frames’ and it was drawn finer. Then it went into a ‘roving frame’, and it was still drawn down finer there. It went through a series of rollers which sort of flattened out the fibres and then the speed of the spindle, with a wee traveller running round the ring, they put in a certain amount of twist and spun it. We spun it at different ‘counts’ the lower the number, the coarser the yarn. For instance 5’s were a fairly thick yarn, anything up to 22’s, 24’s is a much finer yarn. Even these 20’s, 22,s 24’s were still a pretty coarse yarn compared with the finer trade in Lancashire, you know, where they spun the very fine cottons … ….for garments. Our yarns were used for canvas – heavy canvas – mainly used for tents for the army, Bertram Mills’ circus was one of our customers, and tarpaulins for transports. The cloth was proofed after it left our mill in New Lanark, and then it was made up into tarpaulins, and there was quite a lot of repair work done for the circus tents…..’ Jessie Dale, born in the village in 1916, describes working in the weaving department It was very warm there too. It was awful heavy work, and you did perspire an awful lot, and you’d an awful lot of heavy lifts. I racked my back once from lifting heavy weights. Twice I’d a nail off my finger, an accident, - very heavy work. It was men’s work to begin with – all men weavers when they started, and then gradually they roped in women, so at the finish up there were more women than there were men’. And did the women get paid the same as men?’ ‘No, much less. Then latterly they went on to automatic looms and they stopped automatically when there was anything wrong. They were a bit heavy too. And the cotton, there was an awful lot of cotton flying about. You were covered in cotton – your hair was thick with it. And it was quite dirty and oily work. You’d all your machine to clean, and it all to oil. We wore all our older clothes. You never had anything ready for a jumble sale, because by the time you were finished with them…..! You were inclined to maybe get oil on them you know. And then latterly, after that woman got her hair caught in the machine, they made everyone wear a sort of dust-cap to cover their hair. They wore them for a while, and then got tired of them and took them off – but it kept your hair clean’. Further Reading: “Historic New Lanark” by Donnachie & Hewitt, Edinburgh University Press ISBN 0 7486 0420 0 (Available from New Lanark Gift Shop – www.newlanark.org) 3