CONGENITAL PYLORIC STENOSIS IN A FOAL

advertisement

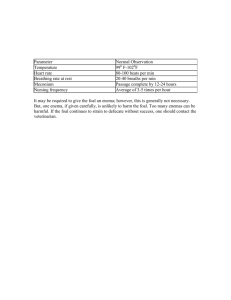

ISRAEL JOURNAL OF VETERINARY MEDICINE CONGENITAL PYLORIC STENOSIS IN A FOAL Kol A.,*, Steinman A., Levi O.,, Haik R.,, and Johnston D. E. Department of Large Animal Medicine and Surgery, Koret School of Veterinary Medicine, Faculty of Agricultural, Food and Environmental Quality Sciences, The Hebrew University of Jerusalem, P.O.B. 12, Rehovot, Israel 76100. Abstract Pyloric stenosis was diagnosed in a 48 hour-old thoroughbred foal that suffered from colic after each suckling since foaling. The foal presented with clinical signs of severe colic that relieved following gastric emptying, with no abdominal distention. It was feeble, depressed, did not suckle, could barely stand and had signs of dehydration and diarrhea all compatible with a surgical lesion of the small intestine. Exploratory laparotomy revealed a pyloric obstruction as the only lesion found. A side-to-side hand sutured gastrojejunostomy was performed. The foal recovered well from surgery and started suckling a few hours later without showing signs of pain. He was discharged from the hospital ten days after surgery and grew normally to the age of six months.At that time the foal developed severe colic which resulted in its death. Post-mortem examination revealed that the colic was caused by a volvulus of the root of the mesentery and did not involve the site of the surgery which had been performed six months earlier.This is the second reported case of congenital pyloric stenosis in a newborn foal. Introduction Pyloric obstruction is common in humans and dogs, but not in horses (1). Pyloric stenosis is either acquired or congenital, however in horses, most cases are acquired (2). Acquired pyloric stenosis is secondary to gastritis, duodenitis, and to gastric and duodenal ulceration, all of which can lead to the formation of granulation tissue and chronic inflammation with fibrosis (3).Two types of congenital pyloric stenosis are known in humans and dogs: neurogenic pylorospasm and muscular hypertrophy of the pylorus (3). Congenital pyloric stenosis in horses has been reported previously only twice. The first report described the condition in a newborn foal that showed signs of colic a few hours after birth (4). The second report described a case of a two-month old Thoroughbred filly with history of stress (5). The condition began at the age of one month, developed into chronic abdominal pain, hence it may not have been a true congenital lesion. Three surgical procedures have been described for relief of pyloric stenosis in foals: pyloroplasty (4,5), gastroduodenostomy, (6,1) and the third procedure included various bypass operations (6). In humans the surgical procedure of choice is Ramstedt pyloromyotomy. The procedure is performed through a short transverse incision or via a laparoscope (7). This report describes a case of true congenital pyloric stenosis in a newborn foal, a rare condition reported only once before (4). The stenosis was treated by a gastrojejunostomy bypass procedure. Case details History A Thoroughbred foal that was born at term, following an uneventful parturition, was showing abdominal pain 3 hours after foaling. The abdominal discomfort was relieved following naso-gastric intubation and gastric emptying. Initial treatment by the referring practitioner included gastric emptying and intravenous (i.v) administration of lactated Ringer's solution (LRS) with 5% dextrose and flunixin meglumine (0.5 mg/kg bwt, i.v). Initially the foal was bright, alert and responsive. However, the foal exhibited abdominal pain for a few minutes following each suckling. After 24 hours the foal’s condition started to deteriorate. Since a gastroduodenal obstruction was suspected, the foal was referred to the Koret School of Veterinary Medicine Veterinary Teaching Hospital (KSVM-VTH). Clinical examination On arrival, at the KSVM-VTH, 48 hours after parturition, the foal was feeble, depressed, did not suckle and could barely stand. Clinical examination revealed a normal temperature, pulse and respiratory rate. Gastrointestinal sounds were reduced and the foal had white pasty diarrhea. Clinicopathologic abnormalities included elevated packed cell volume (40%), elevated total solids (5 g/dl), low plasma electrolytes (Na, 134 mmol/l; K, 2.9 mmol /l; Ca, 1.24 mmol/l) and low white blood cell count (2.7 x 104/mm3). Further diagnostic procedures were not performed due to the signs of severe colic and rapid systemic collapse. Two hours after arrival at the hospital, an exploratory laparotomy was performed. Surgical Treatment Before surgery the stomach was decompressed with a naso-gastric tube and the foal was treated with penicillin ( 40,000 IU/Kg bwt i.v), flunixin meglumine (1 mg/kg bwt i.v) and was vaccinated with tetanus antitoxin and toxoid ( i.m ). An exploratory laparotomy was done through a ventral midline incision starting at the xyphoid cartilage. The entire gastrointestinal tract was evaluated and no abnormalities were found except for a slight visual narrowing of the pylorus and a hard palpable nodule approximately 0.5 cm in diameter in the pyloric lumen. The wall of the pylorus was not thickened. The stenosis was bypassed by a gastrojejunostomy. The duodenocolic ligament was located and the anastomosis was made at the proximal part of the jejunum close to the ligament. A side-to-side anastomosis was performed, using a hand suture method. The jejunum was fixed to the caudal aspect of the pyloric antrum with two stay sutures of 3/0 PDS 6.5cm apart. The first suture line was made with number 3/0 PDS, as a continuous Lembert suture joining the jejunum to the stomach between the stay sutures. Then six centimeter full-thickness incisions of the jejunum and the stomach were made, parallel and close to the suture line. The mucosa and submucosa of the stomach was sutured to the mucosa and submucosa of the jejunum with 3/0 PDS in a simple continuous suture for the full circumference of the two openings. Then the 1800 of the stoma close to the surgeon was oversewn with a 3/0 PDS continuous Lembert suture. The abdomen was closed in a routine manner. Medical Treatment Post-operative treatment included intravenous administration of lactated Ringer’s solution (10 ml/kg/h bwt) with 2.5% dextrose for 36 hours, penicillin G sodium (20,000 IU/kg bwt i.v. qid), and gentamycin (6.6 mg/kg bwt i.v. sid) both for five days, flunixin meglumine (0.5 mg/kg bwt i.v. tid) for three days, and cimetidine (10 mg/kg bwt p.o qid) until the foal was discharged from the hospital. A few hours after surgery the foal was encouraged to stand and suckle once an hour. Bismuth subsalicylate (436 mg total p.o tid) was added 24 hours after surgery for five days to control the diarrhea. Outcome Recovery from surgery was rapid and uneventful, and in a few hours the foal was suckling without showing signs of pain. On the day following surgery, the foal appeared stronger, was standing unassisted and suckled hourly, however diarrhea was still present. Two days later the foal became depressed, showed signs of dyspnea and was coughing. Patent urachus was noticed. Ultrasound of the urachus showed a few hypoechoic areas. Aspiration from a hypoechoic area and cytologic smears revealed non-inflammatory fluids. Radiography of the chest revealed an interstitial pattern in the caudal lung lobe. E. coli was cultured from aspirated abdominal fluids, but no pathogenic bacteria were found in the cultured feces. Treatment included fluids (tap water) via nasogastric tube (5ml/kg/hr) for 30 hours, ceftiofur (4mg/kg bwt im bid) for 5 days, and dipping the umbilicus in a 2% povidine iodine solutiontwice a day for 5 days. The foal improved and was discharged from the hospital ten days following admission. During the hospitalization there was only one episode of pain, which was relieved by decompression of the stomach with a nasogastric tube. At the age of 2.5 month and 6 month, the owners reported that the foal was behaving and developing normally. However, soon afterwards, the foal developed acute colic and was found dead by the referring veterinarian one hour later. On post-mortem examination a volvulus of >3600 was found at the root of the mesentery. The surgical area had a few insignificant adhesions, some fibrosis with no leakage or inflammation. It was remote from the site of the volvulus and did not seem to contribute to it. No explanation was found for the volvulus. Discussion In equine practice there are not enough cases to establish a diagnostic protocol to congenital pyloric stenosis. In our case and the one reported by Crowhurst et al. (1975), a tentative diagnosis was based on history and clinical signs. The diagnosis was confirmed by a laparotomy. A tentative diagnosis of gastric outflow obstruction in dogs is based on the history, signalment, and physical examination findings. Radiography and fluoroscopy, with or without positive contrast studies, provide the most definitive method of diagnosis (9). The diagnosis in humans is established by palpation of the pyloric mass, which is firm, movable and olive shaped. The diagnosis can be established clinically approximately in 60-80% of the cases by an experienced examiner. Abdominal ultrasonography has replaced barium contrast studies in establishing the diagnosis in difficult cases (7). The clinical signs of severe abdominal pain which were evident only following suckling and were relieved by decompressing the of stomach, and the fact that the foal was otherwise normal and free from obstruction by meconium, lead us to several differential diagnoses of small intestinal lesions (congenital defect, intussusception, ilial impaction), all of which require surgical intervention. In contrast to the situation in humans and dogs, we conclude based on this case and the previously reported case (4), that the clinical signs of congenital pyloric stenosis in foals are much more severe and develop more rapidly. The clinical signs start a few hours after parturition and include severe abdominal pain. The foal’s systemic condition deteriorates and must be treated as soon as possible. In the current case we decided that further preoperative diagnostic tests should not be performed due to the rapid deterioration and since all of the above differential diagnoses require surgical interventions. Therefore an exploratory laparotomy was done as quickly as possible. Pyloric stenosis in the horse is most often acquired as a result of chronic EGUS (2). The authors of this paper have found onlytwo case reports of suspected congenital pyloric stenosis. One of those (5), described a case of a two month old filly that, with the current knowledge of equine gastric ulcer syndrome (EGUS), could have been an acquired pyloric stricture secondary to healing ulcers. The second report (4), described a true congenital disorder which is similar ours and was treated with a different surgical procedure. In both reports there was no histological classification of the stenosis. The gross findings in this case are most suitable with focal mucosal hypertrophy. Stenosis of the pyloric canal is one of the more common causes of gastric outlet obstruction in dogs (8). Obstruction of the pyloric canal can be caused by hypertrophy of the pyloric circular smooth muscle, mucosal hypertrophy or both (9). Neurologic or hormonal (gastrin) factors can also play a role (10). Two forms of the disorder are encountered clinically congenital and acquired. The congenital luminal obstruction results from concentric hypertrophy of the circular smooth muscle and the acquired obstruction results from antral/mucosal hypertrophy (9). The most common cause of nonbilious vomiting in children is infantile hypertrophic pyloric stenosis (HPS) (7). The obstruction results from diffuse hypertrophy and hyperplasia of the smooth muscle of the antrum of the stomach and pylorus (11). Low birth weight and increased maternal age were associated with a reduced incidence (12). The cause of pyloric stenosis is unknown, but the offspring of a mother and, to a lesser extent, a father who had pyloric stenosis are at high risk. Another suspected cause is erythromycin. Infants prescribed systemic erythromycin have increased risk of HPS, with the highest risk in the first two weeks of life (13). At surgery in this case, the pylorus appeared to be slightly narrower than normal, and there was a distinct, firm moveable nodule in the pyloric canal. From these findings, the surgeon concluded that there was focal mucosal hypertrophy with no evidence of a muscular abnormality. This is in contrast to the condition in humans and dogs, which involves only muscular hypertrophy. A pyloromyotomy alone was not indicated in this case because the lesion was of mucosal hypertrophy with no involvement of the muscle. Various reconstructive procedures of the pylorus were considered, including penetration of the lumen, however the main determining factor was the severely compromised systemic state of the foal, and speed was essential. The surgeon decided to use the jejunum, which can be exteriorized, for an anastomotic site to the stomach. The pyloric area is difficult to isolate, exteriorize and handle gently, and therefore was left untouched in order to do a safe, rapid and clean surgery. Three surgical procedures have been described for relief of pyloric stenosis in foals. Pyloroplasty was described in foals by Crowhurst et al. 1975 (3) and by Barth et al. 1980 (4). All treated foals recovered and subsequently developed normally. Gastroduodenostomy, which resulted in euthanasia of one treated foal and recovery and normal development of the other three foals, was described by Orsini and Donawick 1986 (5) and by Arnoff et al. 1997 (1). The third procedure included various bypassoperations for relief of obstructions of the pylorus and duodenum as a result of equine gastric ulcer syndrome (EGUS). These operations include gastroduodenostomy after partial resection of the stomach, pylorus and a small segment of the duodenum, duodenojejunostomy followed by jejunojejunostomy to bypass duodenal stricture beyond the hepaticopancreatic ampulla, and gastrojejunostomy followed by jejunojejunostomy to bypass extensive stricture of the duodenum (5). This is the first case that gastrojejunostomy was done alone to bypass pyloric stenosis. After surgery the foal was encouraged to suckle as soon as possible, since he had had almost no nutrition from birth (~50 hours). Recovery from surgery was amazingly rapid and no pain was observed after suckling. A few days after surgery, the foal started to show signs of sepsis, including dyspnea, depression and acquired patent urachus with dribbling of urine. We believe that the foal suffered from failure of passive transfer (FPT). The stenosis was severe, therefore the pyloric canal was probably fully blocked and sufficient colostrum did not reach the small intestines. In cases like this, we would now recommend treating the foal with IV plasma as soon as possible because of the high risk for FPT. In retrospect it should have been done in this foal. The foal was normal at the age of six month and signs of colic were not reported by the owners. We found no connection between the volvulus of the root of the mesenterium that was the cause of death at the age of six months and the gastrojejunostomy surgery at the age of two days. At necropsy the surgical area was not involved in the volvulus and appeared to be in good condition. Referencees 1. Aronoff, N., Keegan, K.G., Johnson, P.J., Wilson, D.A. and Reed, A.L. Management of pyloric obstruction in a foal. J. Am. Vet. Med. Assoc. 210(7), 902907. 1997. 2. McIlwraith, C.W. and Robertson, J.T. Surgery of the gastrointestinal tract. In: Equine Surgery Advanced Techniques, 2nd edn, Williams & Wilkins, Baltimore. pp 299-230. 1998. 3. Vatistas, N.J. The stomach. In: Equine Surgery, 2nd edn, Ed: Jorg A. Auer and John A. Stick, W.B. Saunders Co., Philadelphia. pp 213. 1999. 4. Crowhurst, R.C., Simpson, R.J. and Greenwood, R.E.S. Intestinal surgery in the foal. J. S. Afr. Vet. Assoc. 46(1), 59-67. 1975. 5. Barth, A.D., Barber, S.M. and McKenzie, N.T. Pyloric stenosis in a foal. Can. Vet. J. 21(8), 234-236. 1980. 6. Orsini, J.A. and Donawick, W.J. Surgical treatment of gastroduodenal obstructions in foals. Vet. Surg. 15(2), 205-213. 1986. 7. Wyllie, R. Pyloric stenosis and other congenital anomalies of the stomach. In: Nelson Textbook of Pediatrics, 15th ed, Eds: Behrman, R.E., Kliegman, R.M. and Arvin, A.M., W.B. Saunders Co., Philadelphia. chap. 275(cd). 1996. 8. Hall, J.A. Disease of the stomach. In: Textbook of Veterinary Internal Medicine, 5th edn., Eds: S.J. Ettinger and E.C. Feedman, W.B. Saunders Co., Philadelphia. pp 1169-1170. 2000. 9. Matthiesen, D.T. Stomach: chronic gastric outflow obstruction. In: Textbook of Small Animal Surgery, 2nd edn, Ed: Douglas Slatter, W.B Saunders Co., Philadelphia. pp 561-568. 1993. 10. Fossum, T.W., Hedlond, C.S., Hulse, D.A., Johnson, A.C., Seim, H.B., Willard, M.D. and Carroli, G.L. Benign gastric outflow obstruction. In: Small Animal Surgery, 2ed edn., Mosby, St. Louis. pp 360-363. 2002. 11. Beals, D.A. Pyloric Stenosis Hypertrophic. eMedicine Journal, 2 (9). 2001. 12. Hedback, G., Abrahamsson, K., Husberg, B., Granholm, T. and Oden A. The epidemiology of infantile hypertrophic pyloric stenosis in Sweden 1987-96. Arch. Dis. Child. 85, 379-381. 2001. 13. Mahon, B.E., Rosenman, M.B. and Kleiman, M.B. Maternal and infant use of erythromycin and other macrolide antibiotics as risk factors for infantile hypertrophic pyloric stenosis. J. Pediatr. 139(3), 380-384. 2001.