Willems_2011_Neuropsychologia_suppl_material

advertisement

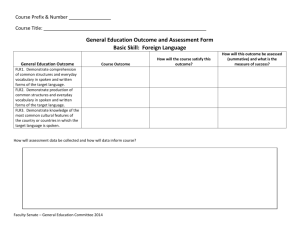

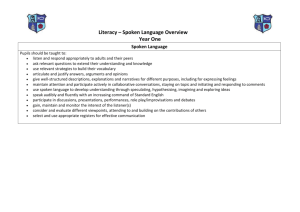

Participant JCB SA PR ST Age (years post-onset) 64 (14) 64 (17) 65 (9) 73 (9) Lexical-semantic assessments ADA spoken word picture matching 58/66 60/66 61/66 55/66 60/66 62/66 66/66 61/66 80/160 123/160 121/160 94/160 (chance = 16.5) ADA written word picture matching (chance = 16.5) ADA spoken synonym matching (chance = 80) ADA written synonym matching (chance = 137/160 121/160 145/160 101/160 80) PALPA 54 spoken picture naming 8/60 0/60 0/60 0/60 PALPA 54 written picture naming 37/60 24/60 2/60 0/60 Syntactic assessments Comprehension of spoken reversible 32/100 49/100 38/100 55/100 48/100 42/100 49/100 62/100 19/40 26/40 21/40 28/40 sentences (chance = 50) Comprehension of written reversible sentences (chance = 50) Written grammaticality judgements (chance = 20) Verbal working memory assessment PALPA 13 digit span (recognition) 2 items 3 items 4 items 3 items 1 Supplementary Table S1. Results of standardised language tests for each aphasic participant. Tests are taken from the Action for Dysphasic Adults (ADA) Auditory Comprehension Battery [1] and the Psycholinguistic Assessments of Language Processing in Aphasia (PALPA) [2] or were devised for the purposes of this study. Spoken and written word comprehension was assessed by word-picture matching and synonym judgment tests, with the latter permitting evaluation of lower-imageability non-picturable words. Patients showed greater impairment in comprehension of low imageability words than high (errors on spoken high imageability pairs: JCB 13; SA 8: PR 7; ST 18; errors on written high imageability pairs: JCB 0; SA 2: PR 0; ST 13; errors on spoken low imageability pairs: JCB 32; SA 9: PR 14; ST 17; errors on written low imageability pairs: JCB 14; SA 19: PR 8; ST 15); Word-picture matching tests required a stimulus word (spoken or written) to be matched to a corresponding picture in the presence of visual, phonological/orthographic, and semantic distracters. Synonym judgment tests involved decisions as to whether two words (spoken or written) had similar meanings. Lexical retrieval was assessed through spoken and written picturenaming tests. Grammatical processing was evaluated by comprehension of reversible spoken and written sentences, and a written grammaticality judgment test. The reversible sentence comprehension tests required matching of a spoken or written sentence to the corresponding pictured event in the presence of a distracter picture showing the reversed roles of the protagonists (e.g., ‘‘The man killed the lion’’ and ‘‘The lion killed the man’’). The stimulus sentences included equal numbers of active and passive sentences to prevent use of an order-of-mention strategy in decoding the sentence (e.g., assuming that the first-mentioned noun is the subject of the sentence). Patients showed impairments on both active and passive sentence comprehension (spoken sentence comprehension (active vs. passive correct) JCB 20 vs. 12, SA 32 vs. 17, 2 PR 24 vs. 14, ST 31 vs. 24; written sentence comprehension (active vs. passive correct) JCB 34 vs. 14, SA 33 vs. 9 , PR 23 vs. 26, ST 33 vs. 29). The grammaticality judgments test required the patient to decide whether a written sentence was grammatical. This task was not performed in the phonological modality to avoid prosodic cues influencing grammaticality judgments. The task examined sensitivity to flagrant violations of English syntactic conventions e.g., ‘sentences’ with no verbs, sentences with postpositions vs. prepositions. Only simple sentence structures were evaluated i.e., a single main clause. Each patient’s short-term phonological memory capacity was determined by a digit span test. Span was established in a recognition paradigm in order to eliminate speech production problems from the task. The patient decided whether two auditorily presented strings of numbers were the same or different. 3 L L L Supplementary Figure S1. Axial slices the anatomical scans of three of the four patients (JCB, PR and SA). Note the extensive damage in the left hemisphere, encompassing the whole peri-sylvian language network. No images are available for patient PZ who cannot be scanned because of contra-indications for imaging. 4 References 1. 2. Franklin, S., J.E. Turner, and A.W. Ellis, The ADA Auditory Comprehension Battery. 1992, York, UK: University of York. Kay, J., R. Lesser, and M. Coltheart, Psycholinguistic Assessment of Language Processing in Aphasia 1992, Hove, UK: Psychology Press. 5