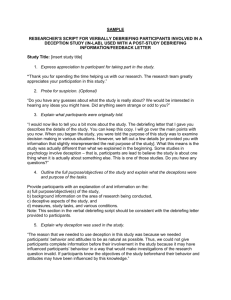

Script - Royal Air Force

DEMONSTRATION STAND

(EXPLORE)

At this first stand, we shall consider the question,

“What deception measures did the RAF employ to protect its airfields from

Luftwaffe attacks? What comparisons can be made with deception techniques employed by Serbia against coalition air attacks during the

Kosovo conflict, and what lessons can be learned?”

Starting, then, with the measures used by the RAF to protect its airfields from

Luftwaffe attack, we will orientate ourselves – where are we, and why?

We’re currently standing on the Northern tip of the main runway of what used to be RAF

Folkingham. (VA01 - Google Map)

The station was originally created as a decoy airfield for the nearby RAF Spitalgate in

Grantham, but was abandoned in late 1941 when daylight air raids ceased.

So we’re here to look at what role Folkingham played in the wider RAF plan to protect its airfields.

Before we start doing that, I’d like to continue with a brief walk down memory lane and tell you a little more about RAF Folkingham to create that link between the past and the present.

In 1943 it was developed as a standard pattern heavy bomber station for Number 5 Group

Bomber Command but, as it was finished in 1944, it was handed over to the American

Troop Carrier Command.

On 6 June 1944, C-47s and C-53s from the 313 th Transport Carrier Group took off from this runway to drop the 82 miles south of St Mere Eglise

– the famous Church in Normandy that featured in the film

‘The Longest Day’. nd Airborne Division into Normandy. The troops were dropped 3

On 17 September 1944, Transport aircraft and Troop carrying gliders also took off from here to drop paratroopers from the British 1 st Airborne Brigade into Arnhem.

We’ve all familiar with the events that followed, even if it is just from watching ‘ A Bridge Too Far”.

After the end of WW2, Folkingham was used for several different purposes. It was briefly a maintenance unit before being transferred to Technical Training Command. It housed

Number 3 RAF Regiment Sub-depot, which trained Gunners for service overseas until mid-1946.

It was inactive again from 1947 until 1959 when it was reactivated to become part of the

RAF North Luffenham Thor Inter-Continental Ballistic Missile c omplex. We’ll talk more about the post-war years later as we explore another area on the site.

In 1963 the airfield was closed. As you can see, quite a historical pedigree on our backdoorstep!!

1

Military Deception

If we turn now to the exam question and look at military deception.

Sometimes we can deceive the enemy merely by giving them something that approximates to what they want to see

….

(Demonstrate

‘Coins Trick’ – mixing British

coins with foreign coins of a similar size, shape & colour)

…you wanted to see the complete range of British coins and were fooled by my addition of a few impostors. Crucial to this was the distance I deliberately put between the coins and you!

Now, deception in war is nothing new. Sun Tzu advocated that, “All military operations involve deception. Even though you are competent, appear to be incompetent. Though effective, appear to be ineffective”.

If we think about Homer’s tale of the Trojan Horse, it is a classic demonstration of deception. The Greeks believed they had been left a gift whereas, in reality, the Trojans had prepared a skilful ploy to attack the Greeks from within.

Military Deception encompasses both denial and deception activities – ‘denial’ hides the real and

‘deception’ shows the fake. It also operates on two levels – strategic and tactical.

Strategic deception is a branch of intelligence that attempts to falsify the bigger picture of the war, misleading the adversary over the strength of forces and what is likely to be done with them. Its use has been decisive in numerous operations in the 20 th Century.

(VA02 - Decoy WW II Tanks) A classic example is the deception strategy to make the

Germans believe we would begin the invasion in Calais. During Operation BODYGUARD, the allies set up an entire decoy/fake army, including the appropriate radio traffic and commanders assigned to lead them – General Patton.

Tactical Deception, on the other hand, operates on the battlefield’ by leading the attacking forces to waste bombs and ammunition on bogus targets or decoys. We’re going to concentrate on the tactical measures undertaken by the RAF. Much of this information has only come to light since the late

‘70s, as it was still considered sensitive material.

RAF Decoy Sites

In 1939, the Air Ministry formed a secret department to oversee ways to fool the Luftwaffe by using decoys and other means of deception. It would be the first time Britain operated a nationally co-ordinated system of decoy targets to mislead enemy bombers. This was the first positive step, since planning for this had started in the early 1930s but was never pursued with any real determination.

(VAs 03 & 04 - Luftwaffe Maps - Spitalgate) In the pre-war years, we had been openly hospitable to the Luftwaffe. If a German officer knocked on the front gate, he would have been welcomed into the Mess, wined and dined and allowed to take photographs! This enabled them to build up a very accurate picture of the established front-line bases.

Therefore, we knew that we could not hide the pre-war well found stations, but would have to concentrate on the smaller satellite stations.

2

(VA05 - Colonel John Turner) Colonel Sir John Turner was given the task of British

Deception Schemes. As a qualified pilot and civil engineer, he was well-qualified to create suitable decoy airfields and had indeed created many of the existing RAF Airfields – including Cranwell. He had drive, enthusiasm, and initiative and he would need all of these attributes to get the new organisation up and running from scratch. To maintain security, his branch became know as the

‘CTD’ (Colonel Turner’s Department!).

Turner reviewed the existing ideas and consulted with frontline commanders to settle tactics.

It’s important to remember that, given the technology of the day, decoys were designed to meet a visual attack – no thermal imaging technology, etc.

(VA06 - Lincolnshire Decoy Sites and their Parent Airfields) His initial proposals were for a series of day decoy airfields 5 or 6 miles from the genuine airfields. Two types were proposed – a simple all grass airfield where take-offs and landings were in any direction, and a more specialised ‘tracked ground’ where aircraft movements were in defined strips.

Either type would have dummy aircraft, together with simple features aping a real airfield

– worn tracks, disturbed areas representing petrol/ammo dumps, windsocks, and crew quarters. The aim was to create a decoy that would be realistic from 6 miles at 10,000 feet. Even that was difficult, as suitable land was scarce

– the best already having been taken up by real airfields.

Turner’s plans for night decoys were simpler, using electric lights to replicate the full lighting of an airfield. He proposed yellow lights to imitate a T-shaped wind direction indicator, red lights for building obstructions and car headlamps to represent taxiing aircraft. These lights would be used to attract a raider, then doused to complete the deception. Night decoys could be placed anywhere, without regard to topography or other features not visible from the air in darkness.

Turner’s next move was to submit requirements for cheap and durable dummy aircraft out to industry tender. Although some companies had made elaborate and convincing decoys, they were simply unaffordable. Turner turned to the British film industry and, in particular, the Sound City Studios at Shepperton. Because of the poor weather in the UK, most pre-war films were made under cover with convincing mock-ups. They had the skills and experience to make realistic set locations to extremely tight deadlines. These film men were to become the backbone of Turner’s department, producing realistic and effective decoys at a fraction of the price of the aircraft industry. Eventually, Turner would move his headquarters to Shepperton Studios.

Now he had the plans and the team of men behind him, Turner set about the task of creating the sites.

K Sites

This brings us nicely back to our current location. Folkingham was used as one of the day decoy airfields – codenamed ‘K’ sites. It was equipped with 10 Fairy Battle decoy aircraft and manned by a SNCO and 10 ORs of the CTD, who were trained to use machine-guns in the Light Anti-Aircraft role. These men also performed the maintenance, and moved the equipment around to simulate airfield activity.

(VA07 - Decoy Airfield from Above (Cold Kirby)) K sites were not intended as a full simulation of a main front-line base, rather as a possible satellite airfield. Hedges were levelled to create open spaces typical of airfields; ¾ sized dummy buildings were

3

constructed from tubular scaffolding, canvas and chicken wire; roads were created using white limestone, and tracks created by turning over the turf.

Even at ground level, they could deceive. There is a tale of a family who sat on the perimeter of an airfield near Thetford for 3 hours waiting for a Wellington bomber to startup and take off, only to find out later that they were all decoys!

The first K-site was in operation by January 1940 and, in total, 36 were created. Some 30 attacks against these sites were recorded but, following the Battle of Britain, there were just 6 attacks on them in 1941. Subsequently, 14 of the sites were closed.

Finally, in October 1941 we recovered a map from a shot-down enemy aircraft which had

11 of the 22 remaining sites marked as decoys. As a result, the Air Ministry closed the K sites and focussed its attentions on the night-time decoys.

Q-Sites

Folkingham was also used as a night-time decoy – codenamed Q-Site from the Naval

Ships that were armed vessels made to look like merchant ships. From the air, Q-sites were designed to look like a runway flare-path and, for authenticity, had obstruction lights and lights to simulate taxiing aircraft.

There were about 170 Q sites built, initially on a simple concept of a T-shape of lights. In general, they were manned by 2 or 3 men who controlled the lights from the safety of a bunker. (VA08 - Bunker Photos) The men would switch on the lights as dusk approached, and then operate the searchlight positioned on top of their bunker - codenamed ‘scarecrow’ – to simulate aircraft movements. Power was provided from a generator inside the bunker and the crew controlled the site from a small operations room.

The bunker entrances were protected by blast walls made from concrete.

The lights were operated frequently, sometimes up to 20 hours per week, to draw attacks.

The pattern of lighting was varied throughout the war to maintain credibility. Certain lights were omitted and introduced to allow recognition by friendly aircraft. Local control of most of the Q-sites rested with the local ARP ops room, although some RAF stns controlled their own Q-sites.

Q sites were extremely successful, drawing over 450 attacks, which accounted for 5% of the ordnance dropped by the Luftwaffe. By the end of the war, the number of attacks on decoy airfields equalled the number of attacks on real airfields!

Folkingham was hit on the night of 6 June 1940.

QF Sites

During some of the initial raids on the Q sites, Luftwaffe dropped incendiary ordnance.

This led Turner to believe that controlled dummy fires might draw attacks from aircraft approaching a target they knew, or believed, to have been hit. This gave rise to a new decoy site – the ‘Quick Fire’.

Turner experimented with burning creosote tins, with roofing felt suspended above, which would give brief flares of light. He even flew with a Bomber Command pilot to view the results, which were remarkably similar to that achieved by real bombers over Germany.

4

This was later refined by the Sound City Technicians to give different visual effects.

19 QF sites were constructed, only 5 were ever lit and just 2 drew enemy attack. The fires were not operated unless there was a definite attack on the protected target, so as not to draw attention to its general area.

However, the idea of lighting fires to draw enemy aircraft to airfields spawned yet another decoy tactic.

Starfish Sites

The incendiary bombing and subsequent fires in the city of Coventry prompted the Air

Ministry to take action. In order to draw the Luftwaffe from our towns and cities, dummy towns know as ‘Starfish’ sites were created in open land between 2-8 miles from the intended target. (VA09 - Starfish Bunker Diagram & Photo) In daylight, the equipment resembled chicken sheds, but at night the boilers and fire baskets looked just like bombs exploding, incendiaries burning and buildings on fire. (VA10 - Starfish Boiler & Fire

Basket)

Again, the Sound City Film Company would be instrumental in creating a viable decoy.

They developed several different designs to simulate different effects of fire, by burning combinations of paraffin, diesel and scrap wood/sawdust.

The Starfish sites were manned by RAF personnel and used in conjunction with lighting decoys – QL Sites – that simulated factories, marshalling yards, shipyards, etc. These QL sites simulated lighting, such as railway signals, welding lights, and even windows that had been poorly blacked-out.

The idea was that the QL sites would fool the pathfinders into dropping their incendiaries, then the Starfish Baskets would be lit to simulate hits on the buildings and draw the remaining bombers in.

Key points:

The technology of the day was visual only. As such, it was much easier to fool the enemy at night

– and this was shown by the relative success of the Q sites versus the K sites.

Between June 1940 – 1941, Q sites received 322 attacks – almost ¾ of their total wartime attacks. K sites had seen just 36 attacks

– their total wartime attacks.

(TRANSLATE)

We now need to translate this to modern operations and see if there is anything we can learn. To that end, I would like to consider …

WHAT COMPARISONS CAN BE MADE WITH DECEPTION TECHNIQUES EMPLOYED

BY SERBIA AGAINST COALITION AIR ATTACKS DURING THE KOSOVO CONFLICT,

AND WHAT LESSONS CAN BE LEARNED?

The NATO Campaign

I don’t intend to cover any of the background to this – we’re all familiar with the use of

5

NATO Air Power in the Kosovo Campaign. In the short term, the aim was to get the

Serbians out of Kosovo, introduce the Peacekeepers on the ground, and allow the refugees to return to their homeland.

The first point I’d like to emphasise is that this was the first use of Air Power where the politicians and the general public genuinely believed that the war could be prosecuted enti rely from the air using ‘precision munitions’. The press briefings undertaken during

Gulf War 1, showing crosshairs and LGBs taking out targets, had given a false sense of what Air Power could achieve.

NATO thought that the air war would not need to last more than a few days, but they seriously underestimated Milosevic’s will to resist. In the end, the bombing campaign lasted from 22 March to 11 June 1999; during those 79 days, some 38,000 sorties were flown.

The campaign was initially designed to destroy the Serbian Air Defences and high-value military targets. It did not start well – bad weather hindered many of the first missions. Air

Operations then switched to attacking Serbian Ground Units, hitting individual tanks and artillery pieces.

The se cond crucial point concerns NATO’s tactics. Given the reluctance to take any casualties, the Air campaign was prosecuted from above 15,000 feet

– that’s nearly 3 miles high! As a result, with the visual targeting equipment we had in the

‘90s, it was still remarkably simple to fool the aircrew into dropping ordnance on cleverly disguised plywood decoys. This deception cost NATO billions of dollars of ‘smart munitions’, in exchange for holes in the ground and destroyed plywood!

Serbian Decoys

Thermal imaging equipment was still ‘early generation’ and quite simple to fool.

Bridges and other strategic targets were defended from laser guided weapons by lighting bonfires made from old tyres

– these emit dense, black smoke which deflected the lasers.

This tactic was further refined into a series of thermally-convincing targets, which would be used to lure NATO aircraft into a SAM ambush.

Serbian radars were reflected off heavy farm machinery, such as old tractors and combine harvesters, to confuse the precision-guided HARM Missiles.

The Serbs used cheap heat-emitting decoys, such as gas burners, to simulate nonexistent positions on Kosovo mountainsides. B-52 bombers routinely blasted these decoys.

(VA11 - Decoy AA Site) Dummy Anti-Aircraft sites were created around targets, hoping to lure NATO aircraft into real SAM ambushes.

(VA12 – Mig 29 Pictures) A convincing fleet of Mig-29 aircraft were created, and moved regularly to fool the NATO targeting staff. The decoys were designed and made by military modellers, and were quite advanced. They could be brought to life electronically and remotely, and used burning kerosene from ‘smoke-boxes’ to complete the ruse.

Although the Serbs only had 14 real Mig 29s, NATO destroyed ten times as many as this!

6

(VA13 - Artillery and SAM Decoys) Fake tanks were built using plastic sheeting, old tires and logs/drainpipes. To mimic heat emissions, ammo crates were heated by crude stoves. Telegraph poles painted black, flanked by old truck wheels, were used to create decoy artillery pieces.

Serbia also employed a series of ‘underhand tactics’ which exposed their ROE and also influenced world opinion through manipulation of the media:

Reporters were regularly steered away from legitimate military targets and shown civilian collateral damage. To exacerbate the effects, blood-stained dolls were often deployed in the rubble.

Serbian commanders also integrated their military vehicles into refugee convoys to disguise their movements and manipulate the NATO ROE to their own advantage.

Evaluation of the Air Campaign

At the end of the conflict, the Chairman of the Joint Staffs, Gen Henry Shelton, claimed that NATO had destroyed 93 tanks, 220 APCs and 450 artillery pieces. European

Inspectors later verified the numbers at just 20 tanks, 18 APCs and 20 Artillery pieces!

Although 50 aircraft were hit, most of these were old and had been intentionally placed as decoys. The vast majority of radar-emitting AA defences were also preserved, simply by not turning them on and exposing them to NATO attack.

However, it was not all doom and gloom for the NATO campaign. Most of the Serbian military infrastructure and airfields had been destroyed, as it proved almost impossible to camouflage them.

One should also not forget the effects-based approach to conflict we now employ. In order to avoid air attack, the Serbs were forced to minimise the movement of their genuine assets, split their artillery and tanks into

‘penny packets’, and didn’t even turn on their AA radars. NATO therefore achieved the effect of seriously degrading the fighting power of the Serbian forces.

The Serb’s success was also enhanced to some extent by NATO’s self-imposed limitations regarding ROE and bombing altitudes, which limited the pilot’s effectiveness.

The lack of NATO Ground Forces also made deception operations easier for the Serbs.

Key Points: The Serbians were facing the world’s most sophisticated combat power, but by using a variety of deception techniques, they were able to reduce the effectiveness of the air campaign

– protecting their military equipment, humiliating NATO, and influencing world opinion. It was only when Milosevic believed that NATO was serious about entering

Kosovo on the ground that he eventually capitulated.

(PROJECT)

So what?

How should the lessons learned in Kosovo influence our thinking for future operations?

7

New Technology inevitably brings new Countermeasures.

(VAs 14 - Decoy T-72,

SCUD, & F-15) Early generation IR sensors could be fooled by the use of simple gasburners and ammunition tins to create a thermal decoy. Today’s decoys are now being professionally created, themselves using technology to defeat technology. For example, most modern decoys have inbuilt IR-defeating technology.

Lack of Military Deception Expertise. Deception is an art and a science, manifested by clever minds. Military members need the training and understanding to be able to detect clever deception tactics, or we will continue to be duped by inferior Machiavellian enemies. Whilst ‘Deception’ is one of the 7 Domains of Information Ops, there is no

Deception Organisation within the UK Forces. We only undertake minimal Passive Ops – cam and concealment!

Western Military Complacency. Finally, and most significantly, Western Military Forces are still susceptible to the use of Deception operations.

Cunning and inventive tactics used by technically inferior enemies can still outwit technological superpowers. Low-tech deception strategies, such as a strategically placed bloodied doll or the use of a loudspeaker to broadcast tank engines, can be extremely effective.

The effectiveness of a deception is not a function of technology.

The story of the Trojan Horse should continue to remind us that even the greatest of nations can be defeated with deception.

Questions:

How can the RAF ensure that we minimise the deception tactics of our current enemies?

Have you encountered any deception tactics used by Coalition, or enemy forces, whilst you were on operations?

8