The Development of Dermatology in the Oxford Region

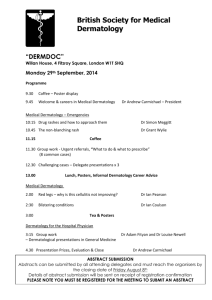

advertisement

The Development of Dermatology in the Oxford Region Terence Ryan Early days The Oxford Medical School can claim that dermatology was there right from the start. St Frideswide in Saxon times cured a student from York of his leprosy by kissing him. In addition, John of Gaddesdon, Chaucer’s Doctor of Physic in The Canterbury Tales, had a stall in St Giles market place where he sold his greases and powders for the skin. His textbook makes good reading for dermatologists.(Rosa Angelicus). However no one could claim that there was much interest in the skin before the 19th Century. The Medical School owned little teaching material apart from a piece of skin from a criminal. Bearing in mind that the clinical school did not begin until 1939, and that previously the hospital in Oxford was an infirmary overseen by general practitioners, one could not expect much expansion in the nineteenth century. There was no great regional community, and the 19th Century Oxford Medical Society attracted its members from no further away than the Cotswolds. Osler and Mallam When William Osler arrived in Oxford he gave his name to several skin conditions (Savin JA. Osler and the Skin. British Journal of Dermatology 2000; 143: 1-8. ), having discovered most of them while he was still in North America. His paper in the B.M.J., which described patients from the Oxford County attending his clinic with vasculitis, has been quoted enthusiastically by myself (Ryan 1976). A physician, Ernest Mallam, looked after skin and venereal diseases for the first three decades of the 20th Century. Alice Carleton Alice Carleton came to Oxford from Dublin in 1921 to teach a few girls, separated from the boys, about anatomy above the waist, in an attic of the Anatomy School. In the 1930s she visited Paris and Vienna and acquired the skills of a dermatologist. Her presence was noted at an early meeting of the British Association of Dermatologists. Her practice was widespread geographically, including Swindon and Cirencester, but she was still teaching anatomy as well in 1950, when I first met her. Only a few years earlier Dr Dowling’s St Thomas’s and Guys’ boys had spread out in the Oxford Region (see below). I avoided Alice in the anatomy school because her wit was capable of destroying me, and I had to struggle to learn the language of anatomy and its long lists of parts. However by 1954 it was time to do dermatology: my father had met her brother and she knew of my existence. This made me work a little harder on knowing my spots. Later I dedicated a book to her, quoting her command “Look boy, look!” She was pleased, saying she had never claimed to advance the subject but found the dedication “entirely acceptable”. The way she practiced dermatology amused her medical students. Every patient was undressed and taught on, and anyone who called a macule a papule might get hit. I was there when she swung round to a female assistant who was nodding a clue to a student from behind her, and punched her firmly in the chest. She had a psychiatrist (Kenneth Dewhurst, best known as a medical historian) in the clinic waiting in case a patient needed talking to. An allergist (Morris Owen) was also there in waiting. All prescriptions were written by the female doctor in attendance who on other days looked after female V.D. In the next room Mary Assinder and Susanne Alexander saw the follow-ups. These clinics were held twice a week and there was a weekly ward round. The dermatology inpatient department had once been the “septic ward” of the infirmary, but now comprised 40 beds at the infectious diseases unit. The occasional lumbar punctures for cerebral syphilis were done there (more whenever the ballet visited Oxford!), but students visiting this outlying unit were rare and saw only special cases such as leprosy or anthrax. I was still a student when Alice Carleton retired, and I helped to drag her car to an “Alice in Wonderland” farewell at the Infirmary on the occasion of her last clinic. I had attended her clinics electively, and when I went off to do my National Service as an E.N.T. surgeon at the Military Hospital in Colchester, I was given the job of being a dermatologist as well. I also had holidays with Alice in France and was introduced in the late `50s to the Hopital St Louis. Alice was correct in saying that she had advanced dermatology very little but because she was a brilliant raconteur, even in French, she was well-known in Europe. Tom Fitzpatrick, who studied pigmentation with Blaschko in Oxford for one year, was also a good friend and Alice was appointed as the Prosser White Lecturer at the old Royal College of Physicians while he was in Oxford. She was very nervous about this - feeling that she had little to offer, but knowing that she was expected to be amusing. She spoke about the history of scabies but it was not a good performance. Tom and I tried to cheer her up at a small dinner party afterwards. During the war she wrote papers on British anti-lewisite (BAL) and published a few significant case histories. She was one of the first to write about hereditary factors in venous leg disorders. She was the first British dermatologist to visit Japan and she published a few anecdotes about this. Her photographer, Tugwell, was superb and the black and white photos in the Oxford Textbook of Dermatology in the 1990s were from that collection and deemed outstanding by reviewers. Dr. Dowling’s boys After the 2nd World War, the following appointments were made: Hugh Calvert (Reading), Darrell Wilkinson (Aylesbury, High Wycombe and Amersham), Ken Crowe (Swindon), and Bob Bowers (Cheltenham). In “the North” (everywhere North of Oxford is Black Country until one arrives in Edinburgh!) Dickie Coles and Ivor Hodgson Jones were based at Northampton. Renwick Vickers Renwick Vickers came to Oxford in 1957. He had learned his dermatology from Rupert Hallam and was appointed as a very young man to assist him in Sheffield. The war saw him in the Royal Navy as a dermatologist and after the war he returned to a busy practice in Sheffield. His philosophy, partly learned from his friend Ingram, was that dermatologists should first and foremost be physicians and must therefore have the “Membership”. This view, supported by Charles Calnan, was a major influence on British dermatology. He also gave a Prosser White lecture, focusing on clinical dermatology and general medicine. The lecture closed with a reference to myself as a student opting for dermatology because I saw it as the least specialized of the specialties (Vickers 1969). Renwick set out to gain local and then national respect for the subject of dermatology. He gave time to the Royal College and became the Chairman of Oxford’s Medicine Board. One of the best gifts I gave him was the opportunity to follow me at the Royal Postgraduate Medical School when he wanted a retirement job. Chris Booth was delighted to have such a distinguished “physician” taking part in the well-known grand rounds. In Oxford, Renwick made special friends with Paul Beeson, the American Nuffield Professor. Although keen to gain respect for dermatology world-wide, he published little and had one tour to Australia, but only after he had retired. Other dermatologists As a registrar, and then as a senior registrar, after Renwick had become wellestablished, I had the job of helping to set up regular monthly meetings, which were attended by regional dermatologists, by American dermatologists from the Upper Heyford Air Base, and by occasional visitors to the Department of Biochemistry, such as Lowell Goldsmith who lived with his family in a wing of my country house. Much earlier, as an unmarried registrar, I had shared my house with R.S. (Charles) Wells while he worked on families with ichthyosis - at first in the Oxford region, and later nationally. An easy lodger, he possessed a small table, which I have kept, and a packet of Kellogg’s cornflakes, which I have not. In the Region we had considerable expertise and initiatives. Ken Crow made a name for himself as an advisor on dioxin and the Sevesco disaster. Bob Bowers had an interest in haemangiomas. Dickie Coles was starting his Group Therapy and used hypnotism for warts. Hugh Calvert was the most widely read, and he had an interest in French texts. Darrell Wilkinson, whose clinics I used to attend while I was a registrar at Stoke Mandeville prior to joining Renwick, had multiple interests and was the region’s most prolific writer. He started me on the topic of leg ulcers. About twice a year we would have a Saturday morning visit to one of the outlying consultants. Records of these meetings are on file. Patient Associations Renwick Vickers and I took up Dickie Coles’ interests and we became the first department to set up a local branch of the Psoriasis Association. We were also much involved with the founders of the Eczema Society. Renwick had a fatherly regard for his patients and after a formal ward round would do his own round, socializing with them. It was natural for Oxford to become the home of the first Camouflage Clinic run by Mrs. Savage, and later formally to set up a consultancy with the Red Cross. Letters to consultants about the role of patient associations and the need for camouflage make diverse reading (I have them on file). Renwick was welcoming to the representatives of the pharmaceutical industry, and so we had much support from Dennis Love of Stiefel and from Seton products - with whom we began to create a new pattern of leg ulcer service based on bandaging. The department had an ex navy male nurse, Mr. Eric Haines (later M.BE.), in charge of VD, leg ulcers and inpatients. On the academic side While I was Renwick’s Senior Registrar, the BAD scheduled him to host the Annual Meeting with the French as our guests. Ken Crow was the local secretary but inclined to depression and to be obsessive compulsive. The role of secretary was too much for him and much fell on my shoulders. It was a chance that Renwick gave me to put on a demonstration of capillary microscopy and also to have a plenary session on the growth of cutaneous blood vessels. (Ryan 1967) I mention this because, while Renwick was single-handedly attempting to give Oxford dermatology its medical flavour, he was conscious that Cambridge had the academic lead through the courses on ‘Biology of the Skin’ that Arthur Rook was organizing. My efforts were regarded as a contribution to science from the department. It resulted in my being promoted to St. John’s Hospital for Diseases of the Skin, the Mecca of Dermatology, under the leadership of Charles Calnan, where I was given my own vascular laboratory for five years. Renwick’s first Senior Registrar in Oxford was Tony Cowan, who studied the silver staining of the cutaneous nerves in psoriasis, working with the anatomist Grahame Weddell. Grahame developed the electron microscope for studying nerve axons in the skin and this attracted the leprosy field. During my time as registrar it was realized that electron microscopy needed fresh material, and not material sent from Nigeria in formalin. Renwick offered two beds for the program, and soon the department became a centre for leprosy research. First Frank Allenby, and then myself organized quarterly meetings for experts on leprosy. Attending these were Robert Cochrane, Paul Brand, Stanley Brown, Michael Walters, Dick Rees, Roy Vollum and Jamison, as well as Grahame Weddell. While I was in London for 4 - 5 years at the Institute of Dermatology, Renwick negotiated with the Nuffield Foundation for an extension to be built onto the in patient department. It was named after, and opened by Robert Cochrane. Colin MacDougall had joined Grahame Weddell from the field of leprosy and TB, and supervised patients admitted to the unit for trials of Chlorfazamine and for rifampicin. The subsequent history is lodged with the Wellcome History of Medicine project and in documents held in 13 Norhams Gardens in Oxford. Later developments Renwick Vickers was appointed as adviser on dermatology to the government. The Dermatology Outpatient Department moved to the new John Radcliffe Hospital and was still separated from its inpatient, administrative and research bases at the Slade Hospital. From time to time the Health Authority, wishing to reduce its multiple site occupancy, threatened to close this site without appropriate planning for resiting the department. Its location, with extensive lawns and mature trees as well as adequate parking, was popular with patients and staff alike. Indeed as special clinics (leg ulcer, PUVA, biopsy and minor surgery, patch testing, leprosy, camouflage) developed, they were based at the Slade. Closure was fought with the help of patient associations and the press. The Health Authority was displeased and Renwick was told by one chairman that any proposal for a ‘national honour’ would be blocked. After his retirement, a second attempt to close the department was fought by me, helped by the Community Health Council and the Media as well as by patient associations. The St. John Ambulance Brigade I had joined St John Ambulance in my days as a registrar, and progressed from Divisional Surgeon to County Surgeon, to Commissioner, and to Commander over a 20 year period. Initially St John was nominally in charge of the Ambulance Service but, by the time I had progressed in authority, a New Health Service authority was created for Ambulance Services. As someone working closely with the Community, I took part in Health Authority planning for nuclear Attack. I managed the emergency services with the Red Cross when the Ambulance Service went on strike or when extra services were required for pop festivals or for the sudden evacuation of armed services and their families from Cyprus to Oxfordshire. My first job was to manage the First Aid requirements for Churchill’s funeral in Oxford. The reason for emphasizing all this as part of the history of dermatology in Oxford is the belief that some of the battles fought for dermatology were won because of the strength of our community/patient organization relationships. Being on the Community Health Council (and Oxford’s was a powerful prototype) was unusual for a hospital consultant, and several years later this was not permitted. The part-time married women’s scheme One of Oxford’s unique pioneering schemes was the ‘Part-time Married Woman’s Scheme’ of Rosemary Rue the Regional Medical Officer. Renwick worked with Rosemary and took full advantage of the popularity of dermatology for the woman with a family. Consequently this was one of the first ways in which an increase in staffing was obtained. Renwick worked hard to get a senior registrar and later to get a second consultant. Parallel activities were the gradually increasing demand for dermatology services and the enlargement of the Medical School. Leg ulcers and lymphatic drainage On my appointment as the second consultant, there was an unwritten belief that I would lead the academic development of the department. I had become an international authority on the blood supply of the skin and maintained that role mostly by reading the non-dermatology literature in that field and taking the Chair of Microcirculation Societies, culminating in the presidency of a World Congress on Microcirculation. I was the first to use the full facilities of the new academic centre of the John Radcliffe. The management of leg ulcers became central to the development of the department of dermatology, which had otherwise concentrated on leprosy. Leg ulceration in Oxford was managed by divers national experts. Mr. Tibbs (surgeon) and Dr. Scott (physiotherapist), the geriatricians, the rheumatologists, and the family practitioners, had a big role to play. In discussions with the Area Health Authorities Medical Officer we were able to put a case for being a Gate Keeper. I had brought George Cherry into the department and eventually persuaded Alec Gatherer to employ him to manage our leg ulcer program. It was a time when many new dressings were being generated and the industry needed clinical trials. These had to be backed by animal trials. George used pigs, and we set up a cell culture laboratory to do basic science work using overseas graduates. Importantly the hands-on management needed skilled nurses. Expertise gradually enlarged and the research potential of nurses became evident. I was asked by nurses working in several fields to help to set up a Nursing Research Group, and facilitate their development through the university. I got myself onto the Regional Authority’s Nursing Committee. I was also appointed to the Board of the new Institute of Nursing and from this was able to appoint more senior nurses to the Department of Dermatology. As it moved from the study of blood supply into the study of lymphatic drainage and of wound healing, the department became the centre for a number of new initiatives. Thus with Peter Mortimer as Senior Registrar we worked with Bob Twycross in palliative care to meet the cry of help from the Post-mastectomy Society for the better management of lymphoedema. We therefore set up the British Lymphology Interest Group and gradually took on leadership in this field - locally, nationally, and internationally. Huge developments in the leg ulcer field were led by George Cherry. He established an annual course on wound healing for young European investigators, and then we joined in and led the establishment of the European Tissue Repair Society, which collaborated with the American Wound Healing Society. Dermatologists played a leading role in both. These contacts enhanced the reputation of the department, and others in the department creating global leadership too. (See below) The profile of nurses George Cherry continued to develop the nursing profile in wound healing up to an international level. I tried, over a period of seven years, to get Oxford University to approve the nurse’s intellectual development - partly to keep them in Oxford and in nursing. I worked with Basil Shepstone and several senior nurses but, partly because their language was educational and sociological rather than science-based, Oxford University refused to allow them entry. They therefore quickly went to Oxford Brookes, where they have flourished. I had attempted to get myself an ‘ad hominem’ chair when the University of Oxford began to open up this possibility to N.H.S. consultants. The very strong Department of Medicine took the first of these. Oxford Brookes gave me an ‘ad hominem’ title of Professor; but I was called to the office of the Regius Professor, Henry Harris, and told not to use it! After a couple of years the University of Oxford appointed me as Professor, and this was an important step forward for the academic reputation of the department. With the nurses in the department, we set up a committee to take their role forward. When I was President of the British Association of Dermatology, we had a combined meeting with the Canadian Association of Dermatology, and I seized the chance to have a plenary session on Community Nursing. By this time I had become Secretary of the International Foundation of Dermatology, the aim of which was to take skin care into the developing world. This organization focused on the training of allied health professionals. Through these activities we set up, in our department of dermatology, the British Skin Care Nursing Group and the International Skin Care Nursing Group. The former soon became affiliated to the British Association of Dermatology and is now its largest branch. The latter is still small but affiliated to the World Council of Nursing. George Cherry then brought another new organization to the department - the European Union Advisory Panel on Pressure Ulcers. These wound-healing initiatives spread the influence of the department world-wide. Other staff appointments When Renwick Vickers retired, Rodney Dawber was persuaded to join us from his successful post in Stoke. Over the next twenty years he established leadership in three fields: cryosurgery, hair and nails. Not only was he a national consultant in these fields, but his many publications and lectures spread his influence world wide. He was especially successful at exciting the younger members to take up research and bringing overseas trainees into the department. When we were able to add a third consultant, Fenella Wojnarowska, further national and international kudos followed, especially in the fields of bullous and vulval diseases. Sheila Powell’s appointment to manage the contact dermatitis field added one more person who was to play a national role. A new building All these activities provided the background to persuading a number of donors to fund a new building. This was helped by the political background of the ‘Thatcher era’, which encouraged such initiatives. Over a decade, several excellent new buildings in the Oxford Region have benefited dermatology. Half the money came from the Dunhill Medical Trust, which had funded my time at the Institute of Dermatology in London 20 years earlier. A substantial grant also came from the wound healing industry. A very fine new building was built in time for a “Celebration of Dermatology” at the 1992 British Association of Dermatology Meeting in Oxford. Recent developments This history goes up to the year 2000. New consultants are expanding our services in dermatological surgery and there is a fine extension to the building for this. Susan Burge has forged strong links with the medical school and the Royal College of Physicians. Several links with leading university laboratories have led to new discoveries. Oxford has trained many consultants but Darrell Wilkinson, and later his son John, have showed huge capacity for enhancement. Not only did Darrell establish the world’s most successful dermatology textbook (his Cambridge colleague Arthur Rook being his leading partner) but he set up links with Australia for training registrars, and a Korean registrar is currently a potential president of dermatology’s leading congress). Darrell developed contact dermatitis clinics before they existed in Oxford and generously, in consultation with myself, set up the channels for my own international reputation and the International Foundation of Dermatology. Unlike the case in Oxford, he won a battle to keep dermatology beds by agreeing to unisex wards. Later he negotiated a fine building for his department in Amersham. Our region continues to demonstrate that dermatologists are friendly and cooperative. Its regional meetings are well attended and carry out formal administrative and advisory functions.