ALTIPLANO DRILLING MANUAL_0

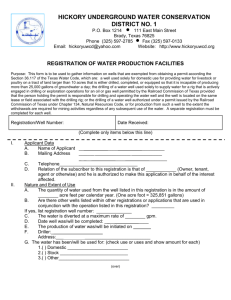

advertisement