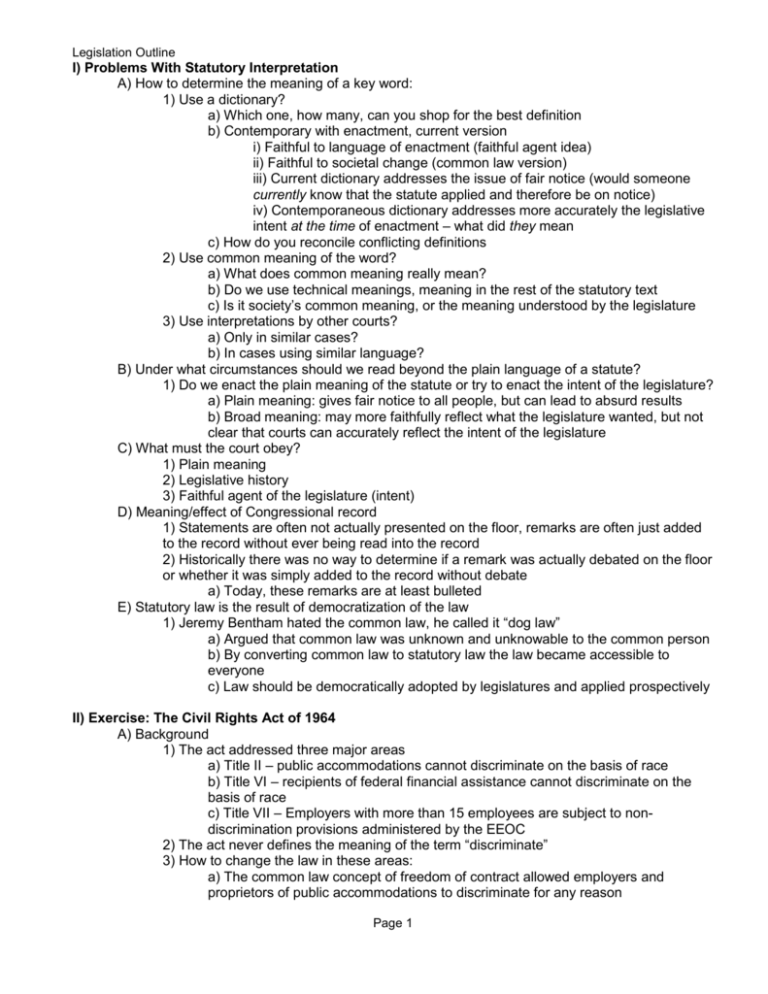

Legislation - Frickey - 2003 Spr - outline 2

advertisement