The impact of the war on women`s lives and

advertisement

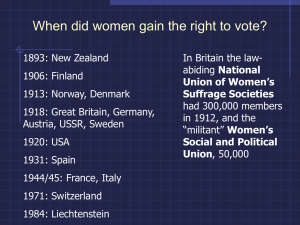

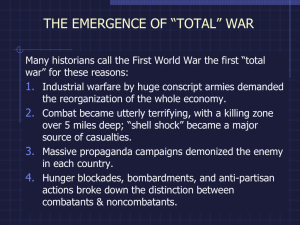

The impact of the war on women’s lives and experiences in Britain. Women were keen to contribute to the war effort, and the main way they did this was to seek employment in many areas of the economy. This meant that large numbers of women also experienced the rigours of total war. The main area of employment for women was the munitions industry. In 1914, it employed 212,000 women; by 1917, the number had risen to 819,000. This represented 60 percent of all workers in the munitions industry. Women also worked in the service industries – in banking, finance, transportation, education, administration and the police force. Women also worked as doctors and nurses, and their political organisations raised money to run hospitals for injured soldiers. The government established a Women’s Land Army to replace agricultural workers who were now in uniform. Women were even allowed to serve as auxiliaries in the army (the WAACs) and air force, where they worked as drivers, radio operators and supply officers. A negative impact of the war on women was that many suffered industrial accidents. 450 alone were killed or injured when a munitions factory blew up in 1917. Many hundreds of women died of TNT poisoning (the ‘canaries’) during the war. As the war continued, the number of women opposing it grew. This was because they were tired of the shortages of food and the deaths of their sons and husbands. These women formed the Women’s Peace Crusade (WPC), and began campaigning actively against the war. They organised street meetings in workingclass suburbs and towns, and handed out anti-war leaflets. On more than a few occasions, their protests were broken up by police, sometimes violently. Women’s self-confidence increased during the war, as did the respect men afforded them. They also developed a sense of independence, having to cope without their husbands or fathers. As a result of having paid work, women became more independent financially. Their wages rose fourfold, to a level much closer to that of men. Women’s fashions changed during the war: their skirts and hair became shorter (enabling them to perform manual work more easily), and corsets were replaced by bras. Women were even able to smoke in public during the war. In essence, the war achieved for women what years of political agitation could not. In February 1918, women over the age of 30 were given the vote, in recognition of their contribution to the war. Unfortunately, most women lost their jobs once the soldiers came home from the war. By 1920, the number of women in the workforce was less than it had been in 1914.