the Provision of Cross-Border Public Services for Wales

advertisement

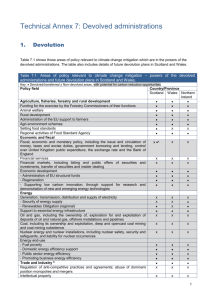

1 Memorandum of Evidence Welsh Affairs Committee Inquiry on the Provision of Cross-Border Public Services for Wales Professor Charlie Jeffery, University of Edinburgh Introduction 1. This memorandum draws on findings from research supported by the Economic and Social Research Council under its research programme on Devolution and Constitutional Change, which ran from 2000-6 under my direction. In particular it draws on work done in collaboration with the Institute for Public Policy Research as reported in books on Devolution in Practice. Public Policy Variations in the UK in 2002 and 2005. 2. It is an inherent feature of devolved systems of government that the packages of public policies experienced by citizens vary from place to place. Devolution in the UK, as elsewhere, is intended, inter alia, to bring greater proximity of decision-making and in that way to reflect better different territorial preferences and identities in public policy in different jurisdictions. 3. It is no surprise, therefore, that devolution here, as elsewhere, has produced greater divergence of public policy. Indeed, post-1999 divergences have built on long-standing practices of territorially differentiation of public policy that are in part rooted in the different terms of union among the different nations of the UK, and the administrative practices developed before 1999 by the Wales, Scotland and Northern Ireland Offices. The UK has long experience of territorial policy variation. The Structure of Devolution 4. But the UK also has a structure of devolution that is very, and in comparative terms, unusually open to far-reaching policy variation and lacks the mechanisms employed elsewhere to balance divergent territorial preferences with overarching state-wide concerns. 5. There are three features of that structure that promote variation. The first is the relatively tidy division of powers between those reserved to Westminster and those variously devolved in Wales, Scotland and Northern Ireland. The division is neatest in the Scottish and Northern Irish cases, though Wales after the 2006 Government of Wales Act is moving in a similar direction, all the more so if a referendum is held and won on full legislative powers. The tendency is to establish four discrete jurisdictions in a range of important policy fields, including health, education, local government, planning and so on. 6. The second feature promoting variation is the UK’s system of financing devolution through block grants transferred to devolved administrations by 2 central government. These grants are transferred unconditionally; the devolved administrations in principle have complete discretion in how they spend those grants. 7. The third feature promoting variation are the different terms of political competition in Wales, Scotland and Northern Ireland as compared to Westminster. Westminster is dominated by a classic left-right contest between Labour and the Conservatives. The Conservatives are very weak in Wales and Scotland, and left-leaning Nationalist parties pull party competition there to the left (while also introducing constitutional questions into party competition that are generally marginal at Westminster). The terms of political debate in Wales and Scotland therefore diverge significantly from those at Westminster, as they do in Northern Ireland, where there is an entirely distinctive party system and constitutional debate. 8. Discrete policy responsibilities, full discretion on spending, and different terms of party political competition have already fostered – and are likely to do so all the more over time – notable territorial policy variations in Wales, Scotland and to a lesser extent Northern Ireland. These extend some way beyond those variations inherited from pre-devolution arrangements. There are few institutional counterbalances to that dynamic of variation. In particular the UK lacks those forms of systematic intergovernmental coordination that exist in most other decentralised states to identify and pursue common objectives across jurisdictional boundaries and to build understandings of the legitimate scope of cross-jurisdictional policy variations and the implications for crossborder relationships that arise. Cross-Border Policy Variation 9. There is a growing number of examples of policy variation. Some of the innovations of the devolved administrations – for example in children’s policy in Wales and on smoking in Scotland – have prompted UK-wide changes. Other devolved innovations – on free personal care, prescription charging, the licensing of NHS treatments, or tuition fees – have not been generally emulated. As significant a source of variation has been Westminster in its role as legislature for England. Its changing approach to the structure and performance management of public services has not been emulated and in many cases has been rejected by the devolved administrations. England also is a force for divergence. 10. A patchwork of different territorial packages of public services has resulted. This – it bears repeating – is entirely consistent with the purposes of devolution. But without an institutional framework for a discussion of the cross-border and UK-wide coordination issues and other implications of crossjurisdictional policy variation, the UK’s policy patchwork is and will remain ad hoc, inconsistent and confusing for the citizen. 11. Some have pointed to the potential for territorial policy variation to corrode the UK’s ‘social citizenship’, the postwar commitment to a welfare statehood that treated all citizens equally irrespective of income or place of residence. 3 Public attitudes surveys suggest that citizens in all parts of the UK share broadly the same values on the role and scope of the state and the obligations of citizens to one another. They also suggest (without the same depth of evidence) that citizens in their majority disapprove of the idea of territorial policy variation (even while endorsing devolved, and therefore potentially divergent decision-making in clear majorities outside England). 12. In these circumstances an under-coordinated structure of devolution runs the risk of producing perceptions of inequity that might lend themselves to political mobilisation. One example of this on a small scale was the recently reported (and, no doubt, methodologically suspect) commercial opinion poll in Berwick-on-Tweed which suggested that the majority of Berwick’s population would prefer re-unification with Scotland to enjoy what are perceived to be better public services there. Equivalent pollster-led skirmishes are conceivable on the Anglo-Welsh border, where in particular different prescription charging policies have been contentious. 13. On a larger scale there have been repeated contributions in some sections of the London-based media, in parts of the Conservative Party, but also parts of the Labour Party in London and in northern England (and more mischievously the Scottish National Party in Scotland) that the arrangements for devolution outside of England are unfair to people in England. A particular focus has been on the seeming connection between the higher level of per capita public spending in Wales, (especially) Scotland and Northern Ireland as compared to England, and the perceived generosity (in some views, profligacy) of public services outside England. 14. These contributions have largely been misguided. They tend to misunderstand both the system used to allocate funding to the devolved administrations, and the pattern and sources of post-devolution policy variation, much of which has been driven by Westminster in England, and in many cases might be said to produce there ‘better’ or ‘more generous’ public services than those available outside England. However misguided, these contributions point to a potential for the political mobilisation of territorial difference. Mechanisms of Cross-Border Coordination 15. To summarise: the post-devolution political system Has a lack of institutional counterbalances to a structure that promotes territorial policy variation And runs the danger – in part through widespread misunderstanding of the reasons for policy variation – of causing conflict over perceived inequities between the component parts of the UK 16. Other political systems provide examples of how more robust institutional balances and more rounded understandings of cross-jurisdictional equity and coordination can be achieved. Among the institutional techniques used elsewhere, but absent in the UK, are: Statewide policy-making by intergovernmental agreement between central and devolved governments 4 Statewide framework legislation leaving a wide scope for detailed regulation and implementation at the devolved level Joint central-devolved funding of agreed common policy objectives Specific-purpose transfers of central funding to devolved administrations to achieve statewide objectives Systems of fiscal equalisation to ensure all jurisdictions have sufficient resources to deliver equivalent levels of services 17. Typically, such institutional techniques are underpinned by codified, routinised and systematic processes of intergovernmental coordination. These processes provide forums for identifying common purposes, resolving any disputes that may arise, managing the interfaces between jurisdictions, and pursuing joint decision-making. They also, through their codes and routines, generate enduring common understandings about the purposes, benefits and limits of territorial policy variation as balanced against statewide objectives. 18. The UK’s system of post-devolution intergovernmental relations is extraordinarily underdeveloped. It would be difficult to assess it as fit for purpose. The UK does have codified arrangements – for example Joint Ministerial Committees – but these in most cases are not used. Intergovernmental relations instead work typically through ad hoc, case-bycase interactions among different and changing groups of officials. There is an absence of routine and as a result a failure to embed understandings of the ‘rules of the game’ in balancing UK-wide and devolved interests. Without clear, enduring common understandings of balance the devolution arrangements remain vulnerable to their own inconsistencies and the consequent danger of partisan mobilisation of territorial conflict. Choices 19. This is an unsatisfactory situation. Its uncertainties are reflected in formal debates about constitutional relationships in Wales and Scotland, and at the UK level in the constitutional ‘review’ or ‘commission’ under discussion by the three main unionist parties. A number of options might be considered in this context: 20. The status quo. The discussion above suggests that the ill-coordinated adhockery of current arrangements is not the optimal route forward. Two alternative trajectories appear possible. 21. Renewal of union. Some mixture of the types of technique listed under paragraph 16. are introduced, and underpinned by a more systematic approach to intergovernmental relations. This option would involve the identification of, and measures to achieve, UK-wide objectives across jurisdictional borders. In doing so, it may require some restrictions on the current scope of devolved responsibilities; it is not clear that the devolved administrations would be willing to accept this. A more systematic approach to joint decision-making would also require a conception in Westminster and Whitehall of powersharing with the devolved administration in the identification and pursuit of 5 common objectives; it is not clear that Westminster and Whitehall would be willing to accept this. 22. A state of the autonomies. This option would not involve the pursuit of a wide range of shared objectives, but rather the acceptance of growing territorial policy variation by the devolved administrations and by Westminster acting for England. In effect England would be governed as a unitary sub-state of the UK by Westminster, while Scotland, Wales and Northern Ireland would pursue autonomous objectives, no doubt on the basis of a fuller devolution of powers than at present, including extensive fiscal autonomy. The effect would be to harden the UK’s internal borders and limit the scope of citizenship rights enjoyed uniformly across the UK. It is not clear that this option would receive public support, for reasons stated above in paragraph 11. 23. These alternatives are presented here in bald terms. Presented baldly they each appear to present difficult problems. No doubt there are elements in them that are reconcilable (for example the Liberal Democrats’ Steel Commission in Scotland proposed devolution arrangements with greater autonomy alongside measures to strengthen the UK union). Yet put baldly they raise issues of principle whose resolution would appear a precondition for sustainable reform: do we want a more consciously integrated union than at present, with limits on the scope of cross-border variations; or are we happy to see far-reaching differentiation in what the UK state does for its citizens from one part of the UK to the next?