Geologic History of the Idaho Batholith

advertisement

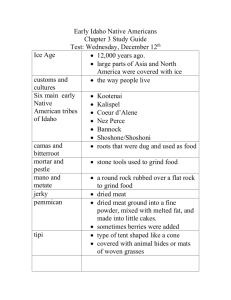

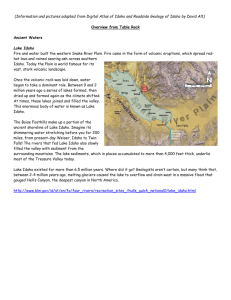

1 - Idaho Basement Rock 6 - Idaho Batholith 11 - SRP & Yellowstone 2 - Belt Supergroup 7 - North Idaho & Mining 12 - Pleistocene Glaciation 3 - Rifting & Passive Margin 8 - Challis Volcanics 13 - Palouse & Lake Missoula 4 - Accreted Terranes 9 - Basin and Range 14 - Lake Bonneville Flood Mesozoic Idaho Batholith by Laura DeGrey, Myles Miller and Paul K. Link, Idaho State University Introduction to the Idaho Batholith Geologic History of the Idaho Batholith Geology of the Idaho Batholith References Batholith Slideshow THIS IS A SHOW OF THE ATLANTA LOBE BY PAUL LINK WE WILL ADD THREE IDAHO BATHOLITH SHOWS FROM JIM CASH, N. IDAHO, BITTERROOT LOBE, AND ATLANTA LOBE. Vocabulary Words batholith granodiorite Farallon Plate subduction isostatic rebound Diagram showing plate configuration at about 80 Ma. 5 - Thrust Belt 10 - Columbia R 15 - Snake River Introduction to the Idaho Batholith The Idaho Batholith is composed of Cretaceous granite and granodiorite and covers approximately 35,000 km2 in central Idaho; it is roughly 320 kilometers long by 120 kilometers wide, and 8 kilometers thick. The Atlanta Lobe and the Bitterroot Lobe of the Idaho Batholith (Figure 1) are separated by Middle Proterozoic Belt Supergroup metamorphic rocks in the Salmon River Arch (Evans and Green, 2003). The Atlanta lobe is older, 100 to 75 Ma, while the Bitterroot lobe is mainly 85 to 65 Ma. The Idaho batholith forms a barrier to travel between northern and southern Idaho . Except for US 95, which follows the Salmon River suture zone through McCall and Riggins, there are no paved roads that cross the Idaho batholith from north to south. Figure 1. Map of Idaho showing the location of the lobes of the Idaho Batholith. Geologic History of the Idaho Batholith The granitic rocks of the Idaho Batholith formed during late Cretaceous compression event. At this time, the dense oceanic Farallon Plate was subducted beneath the more buoyant continental North American Plate. The oceanic crust was subducted into the lithosphere until heat, pressure, and slab dewatering initiated melting of the oceanic plate. This melting and the superheating of water that was also subducting formed basaltic magma chambers. These chambers rose up through the lithosphere because of differences in buoyancy. They then caused partial melting of overlying continental crust, to form a melt of granitic composition. The magma bodies stopped approximately 4-25 km below the surface and cooled slowly (Lewis et al., 1987). The magma then crystallized into the granites and the granodiorites of the Idaho Batholith (Figure 2). This process included many small magma bodies that formed one large mass when they coalesced. Cooling of the magma bodies over different rates and with different timing produced many different crystalline rock types and textures. The rising of the magmatic plutons caused the uplift of large mountains at the surface of the Earth. Thrust faulting occurred to the east in the IdahoWyoming Thrust Belt due to crustal thickening and compression. Isostatic rebound, mainly between 65 and 50 Ma caused erosion of the overlying rock exposing the Idaho Batholith at the surface. Eocene Challis volcanic rocks (50 Ma) rest unconformably on the middle depths of the Atlanta lobe of the batholith, demonstrating this Paleogene uplift. Geology of the Idaho Batholith The Atlanta Lobe intruded between 100 – 75 Ma and the younger Bitterroot Lobe intruded between 85 – 65 Ma. There is a general age-progressive trend from the southwest to northeast, coincident with eastward subduction of the Farallon Plate. Both lobes display compositional zoning from west to east. The Atlanta Lobe contains six types of granitic rocks (King and Valley, 2001). The western boundary of the lobe is composed mainly of tonalite. Muscovite-biotite granite surrounded by biotite granodiorite form the core of the lobe. Other lithologies include hornblende-biotite granodiorite, porphyritic granodiorite, and leucocratic granite (King and Valley, 2001). The boundary between the tonalitic and granitic rocks coincides with the boundary between the Mesozoic Seven Devils volcanic arc including Paleozoic and Mesozoic oceanic rocks on the west juxtaposed with the continental Middle Proterozoic Belt Supergroup and crystalline basement rocks on the east side (Hyndman, 1983). This area is not well understood geologically and recent work by Karen Lund of the U.S. Geological Survey suggests that Mesozoic oceanic rocks (Clearwater Ridge orthogneiss) may be present to the east in thrust sheets. The Bitterroot Lobe contains two main phases; hornblende-biotite tonalite and muscovite-biotite granodiorite (Wiswal and Hyndman, 1987; Vallier and Brooks, 1987). Granitic pegmatites are also found locally within the Bitterroot Lobe (Alt and Hyndman, 1989). According to Hyndman (1983), the tonalites on the west side originated when melting of more mafic, upper mantle, or oceanic rocks occurred near the subduction zone. The granitic intrusive rocks on the east side of the Bitterroot Lobe and of the north and northeast side of the Atlanta Lobe developed by melting of Belt and pre-Belt basement schists and gneisses. The country rocks on the eastern side of the Atlanta Lobe include Paleozoic marine clastic sediments. West of McCall is the Western Idaho Shear Zone (WISZ) where the western side of the batholith is truncated by a right-lateral oblique thrust zone. Tens of kilometers of the western side of the batholith may be missing along this shear zone (McClelland et al., 2000; Lund, 2004). See discussion in the Accreted Terranes module. The eastern side of the Bitterroot Lobe consists of the Bitterroot Metamorphic Core Complex. There is a mylonite zone on the eastern edge of the complex. Eocene-age hypabyssal dike swarms of basaltic and andesitic composition, parts of the Challis magmatic complex) are pervasive throughout both lobes along the Trans-Challis Fault Zone (Jordan, 1994; Alt and Hyndman, 1989). Eocene granitic plutons, slightly younger than the dominant dacitic volcanic and intrusive rocks intrude the Cretaceous granites within the Atlanta Lobe (Johnson et al., 1988; Jordan, 1994; King and Valley, 2001). INCLUDE PDF OF JOHNSON ET AL FIELD TRIP FROM IGS BULLETIN 1988, LINK AND HACKETT. References Alt, D.D., and Hyndman, D.W., 1989, Roadside Geology of Idaho: Mountain Press Publishing Company, Missoula, 393 p. Evans, K.V., and Green, G.N., 2003, compilers, Geologic Map of the Salmon National Forest, and vicinity, east-central Idaho: U.S. Geological Survey Geologic Investigations Series I-2765, two sheets, scale 1:100,000. Hyndman, D. W., 1983, The Idaho batholith and associated plutons, Idaho and Western Montana, in Roddick, J. A., editor, Circum-Pacific Plutonic Terranes: Geologic Society of America Memoir 159, 213-240. Johnson, K. M., Lewis, R. S., Bennett, E. H., Kiilsgaard, T. H., 1988, Cretaceous and Tertiary intrusive rocks of south-central Idaho, in Link, P. K., and Hackett, W. R., editors, Guidebook to the Geology of Central and Southern Idaho: Idaho Geologic Survey Bulletin 27, p. 55-86. Jordan, B.T., 1994, Emplacement and Exhumation of the Southeastern Atlanta Lobe of the Idaho Batholith and Outlying Stocks, South-Central Idaho, [M.S. Thesis]: Pocatello, Idaho, Idaho State University, 110 p. King, E.M., and Valley, J.W., 2001, The source, magmatic contamination, and alteration of the Idaho Batholith: Contributions to Mineralogy and Petrology, v. 142, p. 77-88. Lewis, R. S., Kiilsgaard, T. H., Bennett, E. H., and Hall, W. E., 1987, Lithologic and chemical characteristics of the central and southeastern part of the southern lobe of the Idaho Batholith, in Vallier, T. L. and Brooks, H. C., editors, Geology of the Blue Mountains Region of Oregon, Idaho, and Washington: The Idaho Batholith and its border zone, U. S. Geological Survey Professional Paper 1436, p. 171-196. Lund, Karen, 2004, Geologic setting of the Payette National Forest and vicinity, Westcentral Idaho: U.S. Geological Survey Professional Paper 1666-A, 89 p. McClelland, W.C., Tikoff, B., and Manduca, C.A., 2000, Two-phase evolution of accretionary margins; examples from the North American Cordillera : Tectonophysics, v. 326, no. 1-2, p. 37-55. Vallier, T. L., and Brooks, H. C., 1987, The Idaho Batholith and its border zone: A regional Perspective, in Vallier, T. L. and Brooks, H. C., editors, Geology of the Blue Mountains Region of Oregon, Idaho, and Washington: The Idaho Batholith and its border zone, U. S. Geological Survey Professional Paper 1436, p. 1-8. Wiswall, C. G., and Hyndman, D. W., 1987, Emplacement of the main plutons of the Bitterroot lobe of the Idaho Batholith, in Vallier, T. L. and Brooks, H. C., editors, Geology of the Blue Mountains Region of Oregon, Idaho, and Washington: The Idaho Batholith and its border zone, U. S. Geological Survey Professional Paper 1436, p. 59-72. Continue to Module 7 - Geology of Northern Idaho and the Silver Valley