Telework and Federal Employee Dependent Care

advertisement

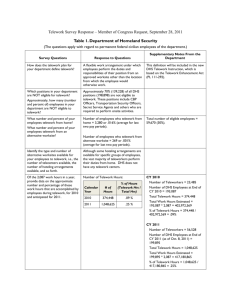

Telework and Federal Employee Dependent Care Author: Joice, Wendell; Verive, Jennifer Source: Public Manager 35, no. 3 (Fall 2006): p. 44-49 ISSN: 1061-7639 Number: 1159208151 Copyright: Copyright The Bureaucrat, Inc. Fall 2006 -------------------------------------------------------------------------------A recent government study takes a comprehensive look at the use of federal employee telework to help manage care-giving duties. Public- and private-sector employers are adopting telework, which is moving into the mainstream of workplace management. A 2005 study by the International Telework Advisory Council (ITAC) estimated that 45.1 million Americans telework from home, up from 44.4 million in 2004. Included are nearly 10 million salaried employees who telework at least one day per month, an increase from 7.6 million in 2004. Facilitating this trend in the public sector is Public Law 106-346, which requires federal agencies to offer the opportunity to telework, at least one day per week, to all eligible employees. One benefit commonly associated with telework is its potential for assisting employees with dependent care responsibilities, such as taking children to doctor appointments, keeping a disabled spouse on a medication routine, or looking after the needs of an elder. Yet, many organizations do not support the use of telework to assist employees with dependent care responsibilities; in fact, the standard practice is often to exclude this option in telework programs. The typical reasoning for this exclusion is the belief that telework should not be a substitute for dependent care and that blending the two reduces the quality of work and dependent care. From the beginning of the telework movement, the dependent care policy mantra has been that "telework is not a substitute for dependent care." A Web search of organization telework policies reveals that most (1) touch very briefly on the matter (other than a statement of the aforementioned policy mantra) or (2) provide the dependent care exclusion statement along with elaborate details and prohibited practices regarding telework and dependent care. Some policies go so far as making telework participation contingent on employee (written) certification that dependents are cared for (during business hours) by another individual or program. Such policies place management in a position of intruding into the employee's personal life. Management concern is clear: teleworkers will spend official work hours taking care of dependents as opposed to performing their employee duties or at least will be distracted from their work by the circumstances. However reasonable this concern may seem, the reality is that it is likely based on an outdated subjective view rather than empirical evidence, and the resulting standard approach may not be the best practice. A contributing factor to the outdated opinions and lack of progress in this area is the organizational anxiety over the issue, which has inhibited the usual research and evaluation needed to form a valid basis for policy and practice. In fact, empirical treatment of any kind for this issue has been minimal, if not lacking altogether. Over the years, telework's potential in mitigating employee dependent care problems has been mentioned, but only anecdotally. Recent Federal Study Earlier this year, to stimulate constructive dialogue and develop a basis for policy recommendations for program improvement, the U.S. General Services Administration (GSA) conducted a government-wide study of employee perceptions of telework as a tool for dependent care needs. GSA plans to use the findings as a basis for review and revision, if needed, of relevant policies. The findings from this study are likely to apply to state and local government and private-sector programs, so they can also serve as a basis for information exchange and policy and program practice considerations beyond the federal government. Study Goals and Objectives This study empirically explores the role of telework in assisting federal employees with managing their dependent care responsibilities. As mentioned, most current organizational policy, practice, and guidance is based on telework lore and tradition as opposed to empirical data. The research goal was to develop a more comprehensive, data-driven understanding of the prevalence, handling, and utility of federal employee use of telework to help manage caregiving duties. The key research questions were as follows: * What sort of dependent care needs do teleworking employees have? * Do their teleworking arrangements allow federal employees to better manage their dependent care needs? If so, how? If not, why not? * What can federal agencies do to use telework, and other flexibility programs, to more effectively assist employees with their dependent care responsibilities? Federal agencies are certainly an appropriate population for this study. Like most other employers, private or public, they tend to prohibit or significantly restrict teleworking arrangements as a means of assisting with dependent care situations. Moreover, because agencies have been mandated to allow telework for all eligible employees, they, perhaps more than other types of employers, need to be very clear on the eligibility standards. Thus, understanding how and when telework might acceptably assist with dependent care situations is of particular importance to federal agencies, which must meet mandated telework opportunity rates. Approach GSA recruited twenty-seven agencies and subagencies to invite their respective teleworkers to complete an online survey. Respondents included 863 federal teleworkers with dependent care responsibilities. The majority of respondents were female (73 percent), were thirty-one to fifty-nine years old, and had one or two dependents. The majority of the dependents (81 percent) were children. Findings Organizational Anxiety As expected, several agencies declined to participate in the study due to concern over management reactions or other apprehension regarding the issue, demonstrating their organizational anxiety. At least two large organizations expressed additional concern that participating in such a survey would cause an adverse management reaction that would harm the program. Telework Impact on Dependent Care Ninety-one percent of the respondents reported that teleworking helps with their dependent care needs: offering flexibility, helping with emergencies, giving the ability to transport dependents to appointments, enabling more time for personal life, allowing coordination of care, etc. Telework Impact on Care-Giving Employee The majority of respondents reported that the dependent care assistance from telework helped reduce their stress (88 percent), increase their energy for dealing with dependent care responsibilities (77 percent), and balance their job and dependent care responsibilities (97 percent). Telework Impact on Job Performance The majority (60 percent) of respondents reported that dependent care assistance from telework helped them improve their job performance. Thirty-two percent reported no impact on job performance, and 8 percent reported they did not know. Telework Impact on Other Organizational Factors Nearly all (93 percent) respondents reported their telework participation increased interest in continuing employment with their organizations, and 98 percent reported other benefits to their agencies, such as reduced sick and family leave usage. Changes Needed to Improve the Telework Program When asked if program changes would enable the telework program to better assist with employee dependent care situations, 45 percent said yes. General themes of open-ended responses included policy changes to provide (1) more flexibility in telework types and arrangements, such as allowing more frequent and permanent or fixed telework arrangements instead of only "as needed" and (2) official approval of dependent care or other personal activities as part of the telework program, so long as job performance is not reduced. Table 1 ranks program change categories recommended by the respondents. Table 1. Telework Program Improvements Recommended by Respondents Discussion Impact of Care-Giving More and more employees are finding themselves responsible for some type of dependent-an elder, spouse, disabled relative, infant, young child, teen, etc. The number of employed individuals who are caring f35, no. 3 (Fall 2006): p. 44-49or aging parents, other elders, or aging spouses is rapidly growing. So significant are the trends of parents simultaneously caring for elders, that this generation of parents has been described as the "sandwich generation." Longer working hours exacerbate the challenge of providing quality care for this variety of dependents. These trends indicate that a growing number of employed individuals must balance heavy workloads with traditional and new care-giving demands. Unfortunately, without assistance, this balancing act can adversely affect all parties involved. Care-giving employees are more likely to arrive to work late, leave early, make care-related phone calls, and tend to other dependent care tasks during work hours. These behaviors directly affect organizations' bottom lines. Employees who are caregivers for elder dependents are absent twice as often as noncaregivers, and research has quantified the cost of this absenteeism along with related costs at billions of dollars. One study found that 10 percent of caregivers quit their jobs to dedicate more time to caring for an elder. Finally, the loss of $1 million in wages and benefits in a single year has been reported for one organization due to employees who missed work to care for a child. Leave Usage Unplanned work stoppages caused by disasters or weather shutdowns are unavoidable for most employers. But well-managed organizations striving to minimize the impact of such stoppages are learning that telework is one of their most effective allies in protecting workforce productivity. The organizational impact of employee illness, sick leave usage, and other unscheduled absenteeism is substantial. Employees with dependent care situations, especially those with children, are probably more susceptible to catching contagious illnesses (from their dependents) and more likely to need to take unscheduled leave to handle dependent care issues. According to a 2005 report published on CNN Money.com, "Costs for missed work days can pile up, with unscheduled absences running employers an average of $660 an employee each year, up from $610 (the previous year)." Moreover, the report indicated that nearly half of the employers participating in an earlier survey reported that sick employees at the workplace create problems for both productivity as well as the spread of contagious illness. Fearing lost productivity from these circumstances, employers are using a variety of strategies to remedy this situation. Telework is a beneficial strategy, not only for easing the impact of illness on the employee, but also for easing such impact on productivity and the bottom line. One study found that teleworkers could reduce the amount of lost work time associated with sick or miscellaneous leave by 50 percent or more. Indirect Effects Besides the direct effects of balancing work and care-giving demands, there also are indirect effects such as role conflict (whether it is family that interferes with work or work that interferes with family) that impair care-giving employees and their organizations. First, care-giving employees report less job satisfaction and lower organizational commitment than do non-caregivers. Given that industry norms on the cost impact of turnover range from 100 to 330 percent of a positions salary, the impact of the aforementioned employee attitudes on the organization can be substantial. second, a Parents at Work study found that one in five working mothers reported their marriages were at risk due to role conflict. Although the latter is a seemingly personal issue, research has found that U.S. organizations lose $6.8 billion annually due to absenteeism attributed to marital distress. Third, care-giving employees report negative effects of role conflict on their physical and mental health, which translate into higher costs for employers in terms of increased utilization of healthcare and employee assistance program benefits. No doubt, the indirect effects of employees' inability to effectively manage work and dependent care can strongly and negatively impact their employers' bottom line. General Benefits of Telework The findings of the GSA study mirror traditional findings of telework program benefits to employees, management, and the organization. Respondents point out numerous quality-of-life benefits to themselves and to their families and dependents, including minimal time off for dependent care purposes, improved morale and lower stress leading to better job performance, and increased intention to stay with their employers (improved retention). Thus, telework helps create a work-life balance for employees with dependent care issues as well as a balance of program benefits for the organization, its management, and the employee. Continuity of Operations and Business Continuity Planning The events of 9/11 have led the federal government to emphasize risk management and business continuity planning. Organizations have begun to consider new tools to better manage such workplace issues, and one is the move toward telework. The integration of telework into continuity of operations (COOP) and disaster preparedness and recovery is growing. Establishing a policy of telework for the optimal number of employees enables them and their organizations to recover more quickly from work stoppages. Because many of these employees have dependents who also may be affected by work stoppages, telework provides greater flexibility and opportunity for those employees to handle their dependent care responsibilities, with minimal interruption in the work process. All too often, business continuity or COOP plans do not take into consideration people needs-especially employee dependent care-during a disaster recovery scenario. A 2005 ITAC survey noted the following: "Traditionally, disaster recovery has been concerned with protecting information systems, with little or no attention paid to the people who use those systems." "Few plans addressed the possibility of loss of workplace access or, worse yet, loss of workers. Sadly, 9/11 was a wake-up call for continuity planners. It became tragically apparent that continuity planning had to consider people issues. Increased threats of terrorism, infectious epidemics and workplace violence have forced organizations to reevaluate business continuity plans and include human factors in their deliberations. One of the results of this reevaluation was the realization that telework is a viable tool for dispersing a company's most valuable asset: its people." Management Concerns and Results-Based Management The management concern over performance and distraction in a dependent care telework scenario should be handled in the same way that standard telework is handled and, actually, in the same way that nontelework is handled. That is: managing by results. Management by results always has been a key theme of effective telework programs. Management focus on obtaining expected job performance results from employees precludes the need to be concerned about the household dependent care dynamics in telework arrangements with employees who have dependent care needs. A key function of successful management is providing a work environment and workplace that enables both optimal job performance as well as the best quality of work-life. The findings of the GSA study (improved job performance and quality of work-life) and the effectiveness of managing by results make it clear that sensitivity to the issue and inappropriate policies are not justified, serving only to prevent the organization from being a high-performance workplace. The success of the current focus on pay-for-performance will depend on management's ability to identify and manage results, so an effective application of managing by results not only will enable organizations to facilitate the operation of telework programs for employees with dependent care needs but also will enable them to achieve improved bottom-line cost and job performance. Conclusion The findings and related considerations discussed in this article support the assertion that telework can facilitate work-life balance for employees with dependent care issues while simultaneously creating a balance of program benefits for the organization, its management, and the employee. The GSA study also points out that a key problem in effectively using telework to help with dependent care situations is that current program policies and managerial perceptions often create an atmosphere in which the balanced use of telework for work and dependent care is not only hampered but considered inappropriate and unacceptable. The findings further suggest that organizations would be well advised to take affirmative steps to establish the following: * Clear policy of the appropriate role that telework can play in balancing work and dependent care without diminishing job performance * Top-down support to dispel the anxiety and sensitivity associated with the proper use of telework as a dependent care solution and to help managers and policymakers accept, manage, and promote the work-life (work and dependent care) balance potential of telework * Organization-wide awareness and promotion of the organizational benefits accruing from effective telework/dependent care policies and arrangements * Organization-wide skill development, training, and utilization of managing by results as the predominant management strategy. Caring for dependents is a growing challenge in employees' lives. To be effective, employers such as federal government agencies need to better understand this phenomenon and put effective practices into place that support care-giving employees. The results of the GSA study demonstrate that telework is such a practice and that it can be made more effective by revising the current standard practice of restricting telework as a dependent care solution and, instead, establishing it as an acceptable and supported practice for enabling employees to better meet their dependent care responsibilities. Over the years, telework's potential in mitigating employee dependent care problems has been mentioned, but only anecdotally. References Federal Emergency Management Agency. Federal Preparedness Circular 2001 FPC 66. 2001. http://www.fenia.gov/pdf/library/fpc66.pdf. ITAC. Exploring Telework as Business Continuity Strategy. 2005. http://www.workingfromanywhere.org/telework/twaresearch.htm. Joice, W. "The Evolving Workplace: Avoiding Costly Work Stoppages through Telework Solutions." The Public Manager, Vol. 29, No. 2 (2000), pp. 45-48. U.S. Council of Economic Advisers. Families and the Labor Market, 1969-1999: Analyzing The "Time Cmnch. " (Washington, DC: U.S. Council of Economic Advisers, 1999). http://www.clinton4.nara.gov/media/pdf/famfinal.pdf. U.S. General Services Administration. Is Standard Practice Best Practice? Emerging Perspectives on Telework and Dependent Care. (Washington, DC: U.S. General Services Administration, 2006). http://www.gsa.gov/telework. Wendell Joke, PhD, is the leader of the government-wide alternative workplace arrangements team in the Office of Governmentwide Policy, U.S. General Services Administration. He can be contacted at wjoice@erols.com. Jennifer Verive, PhD, is a founder and CEO of White Rabbit Virtual, Inc. (hup://www.wrvinc.com), where she develops research-based tools and training programs for remote and mobile workers. She is a member of the telework advisors for ITAC (http://www.workingfromanywhere.org), WorldatWork's Telework Advisory Group (http://www.worldatwork.org), and adjunct faculty at Western Nevada Community College. She can be contacted at jverive@tvrvinc.com. This article was adapted from a more thorough paper, including extensive bibliographical references and citations from both public and private sector research. You can access the unabridged research paper at www.gsa.gov/telework.