William Blake

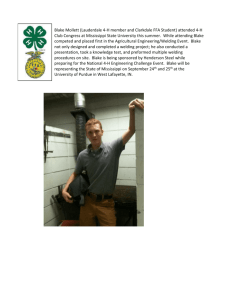

advertisement

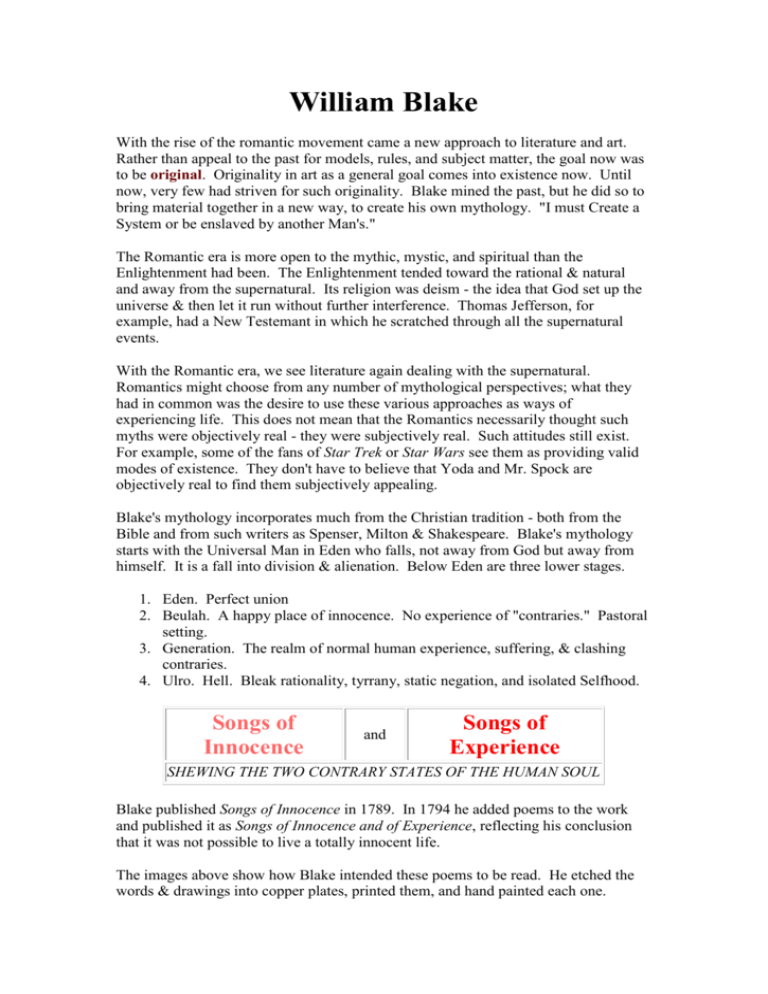

William Blake With the rise of the romantic movement came a new approach to literature and art. Rather than appeal to the past for models, rules, and subject matter, the goal now was to be original. Originality in art as a general goal comes into existence now. Until now, very few had striven for such originality. Blake mined the past, but he did so to bring material together in a new way, to create his own mythology. "I must Create a System or be enslaved by another Man's." The Romantic era is more open to the mythic, mystic, and spiritual than the Enlightenment had been. The Enlightenment tended toward the rational & natural and away from the supernatural. Its religion was deism - the idea that God set up the universe & then let it run without further interference. Thomas Jefferson, for example, had a New Testemant in which he scratched through all the supernatural events. With the Romantic era, we see literature again dealing with the supernatural. Romantics might choose from any number of mythological perspectives; what they had in common was the desire to use these various approaches as ways of experiencing life. This does not mean that the Romantics necessarily thought such myths were objectively real - they were subjectively real. Such attitudes still exist. For example, some of the fans of Star Trek or Star Wars see them as providing valid modes of existence. They don't have to believe that Yoda and Mr. Spock are objectively real to find them subjectively appealing. Blake's mythology incorporates much from the Christian tradition - both from the Bible and from such writers as Spenser, Milton & Shakespeare. Blake's mythology starts with the Universal Man in Eden who falls, not away from God but away from himself. It is a fall into division & alienation. Below Eden are three lower stages. 1. Eden. Perfect union 2. Beulah. A happy place of innocence. No experience of "contraries." Pastoral setting. 3. Generation. The realm of normal human experience, suffering, & clashing contraries. 4. Ulro. Hell. Bleak rationality, tyrrany, static negation, and isolated Selfhood. Songs of Innocence and Songs of Experience SHEWING THE TWO CONTRARY STATES OF THE HUMAN SOUL Blake published Songs of Innocence in 1789. In 1794 he added poems to the work and published it as Songs of Innocence and of Experience, reflecting his conclusion that it was not possible to live a totally innocent life. The images above show how Blake intended these poems to be read. He etched the words & drawings into copper plates, printed them, and hand painted each one. At first glance, these poems seem to fall into traditional Christian moral dualism (the idea of good vs evil, God vs Satan, etc.). But both innocence and experience are elements of the Universal Man that have become alienated from each other. Each needs the other to be complete, which is more like the Taoist yin & yang (female & male. passive & active. dark & light, etc.) than the Christian God versus Satan. Innocence is meek & gentle, but it is also passive & weak. Experience is harsh & terrifying, but it is also strong & energetic. "The Lamb" (p. 1289) and "The Tyger" (p. 1296) Blake employs the image of the lamb, an ancient symbol of gentleness and humility, contrasting it with the tyger stalking its prey. The lamb, with "wooly bright" clothing, plays in the pastoral setting of stream, mead, and vales. The stream, mead (meadow, pasture) and vales are images we see in Psalm 23, a likely source for Blake. Psalm 23 1 The LORD is my shepherd; I shall not want. 2 He maketh me to lie down in green pastures: he leadeth me beside the still waters. 3 He restoreth my soul: he leadeth me in the paths of righteousness for his name's sake. 4 Yea, though I walk through the valley of the shadow of death, I will fear no evil: for thou art with me; thy rod and thy staff they comfort me. Blake sanitizes "the valley of the shadow of death" into "Making all the vales rejoice!" There is no such valley in Beulah, the pastoral world. With innocence portrayed this way, no wonder Blake considered experience to be necessary. The second stanza answers the question of the first stanza. The Lamb who made the lamb is obviously Jesus. The tradition of seeing Jesus as a lamb goes back to the New Testament, where Jesus becomes the Passover Lamb. "The next day John seeth Jesus coming unto him, and saith, Behold the Lamb of God, which taketh away the sin of the world" (John 1: 29). Blake makes Jesus the representative of innocence: He is meek & he is mild. He became a little child; Blake portrays Jesus' goodness as meek, mild, & weak (little children don't have adult strength), almost as goody-goody rather than good. "We are called by his name." Children are sometimes called little lambs. Blake could be referring to the speaker's status as a Christian "The Tyger" contrasts sharply with "The Lamb." The lamb is innocent. To the tyger, it's also delicious. If we compare the meters of the 2 poems, "The Lamb" follows a regular pattern. The first two and last two lines of each stanza have 6 syllables (1-2, 9-10, 10-11, 19-20). The middle six lines in each stanza have 7 syllables per line (3-8, 13-18). The effect of the meter gives us the feeling of a lamb skipping through the fields. "The Tyger" follows a less regular pattern. Most lines have 7 syllables, but some have eight (4, 10, 11, 18, 20, 24), and one line has only 7 syllables (6). The rhythms and sounds of the poem evoke the predator tiger rather than the innocent lamb. If the lamb was "wooly bright," the tyger is "burning bright." It's time in night. It is active rather than passive, hard rather than soft. The opening question of each poem is similar - where did you come from? But the tone of each is different. What god COULD create the "fearful" (frightening) tyger (4)? What god DARES do so (24)? If the lamb was created by the Lamb of God, who created the Tyger? Did he who made the Lamb make thee? (20) Are the lamb & tyger manifestations of the same divinity? Perhaps, but the imagery is as different for the creators as for the creatures. The tyger has been put together in the underworld and is a creature of the night. These are the tools of the tyger's creator: fire sinews hammer chain furnace anvil These are the tools of the blacksmith. Thus Blake has modeled the tyger's creator on the ancient god Vulcan/Hephaestus, the blacksmith of the gods who worked inside a volcano making Zeus' thunderbolts. "The Garden of Love" (p. 1297) In some of our reading, we have come across the idea of sex without guilt, remorse, or bad consequences. Paradise Lost and "The Passionate Shepherd to His Love" are 2 examples. What is it that makes sex fall from this paradisal condition? According to orthodox theology, it was the fall of Adam & Eve. Sex is now part of our sinful fallen nature & must be circumsized with rules to keep it from becoming destructive. For Blake in this poem, it is the prohibition itself that makes sex guilty. To borrow from a NRA bumper sticker, "When sex is outlawed, only outlaws will have sex." He goes to the Garden of Love but finds that his earlier Eden has undergone the fall & is now a chapel. This chapel has "Thou shalt not" written over the door. It is defined by its prohibitions, especially the one against adultery. Priests busily bind his "joys & desires" with "briars." They turn something fun into something painful. What is in the churchyard? A cemetary. Graves (death) have replaced the flowers (life) that were once here. "Infant Joy" (p. 1299) and "Infant Sorrow" (p. 1299) Blake contrasts innocence in the newborn with experience. Even when we are first born, we bear the marks of alienation and contraries. In the first poem, the infant gives itself the name Joy. The smiling baby inspires the adult to sing. The joy spreads. In the second poem, the sorrow also spreads. The baby is born with its mother groaning from the birth-pangs and with the father weeping. The baby is "piping loud; / Like a fiend hid in a cloud." Unhappy babies can cry and disrupt those around them. This baby struggles against its father, against its swadling clothes, and sulks upon its mother's breast. Even food doesn't make it happy. Could this be the same infant? "To Tirzah" (p. 1300) Tirzah was the capital of the Northern Kingdom of Israel, Jerusalem of the Southern Kingdom. Blake uses Jerusalem to symbolize spiritual generation & immortality, Tirzah to symbolize material generation & mortality. Blake treats life in the body as difficult, mortal, and sorrowful. Jesus died to release us from this life, from which Blake accordingly turns away. There is an ancient idea that the body is a prison for the soul that Blake seems to follow here. "The Divine Image" (p. 1291) The Human Abstract" (p. 1298) "A Divine Image" (p. 1299) "The Human Abstract" shows that the innocent, "good" human emotions and actions have roots in the world of experience. We would not need pity if there were no poor, etc. Peace comes from mutual fear (As in the Cold War, where their atom bombs kept us from launching ours & vice versa). God may dwell in us, but so does Deceit. "A Divine Image" contrasts with "The Divine Image" point by point. "The Divine" "A Divine": Traits "A Divine": Source Heart mercy cruelty hungry Gorge Face pity jealousy Furnace seal'd Dress peace secrecy forged iron Human form love terror fiery Forge