2 Queen Elizabeth in Front and Mary Ann Behind

advertisement

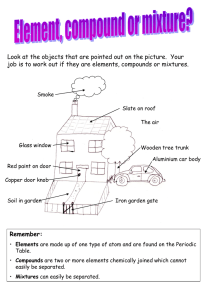

QUEEN ELIZABETH IN FRONT AND MARY ANN BEHIND After the War my father began civilian medical practice as an assistant doctor in Anfield in Liverpool. It was not long, however, before he moved to the Isle of Man. Annie, my maternal grandmother, had rented a house at South Cape near Laxey and my parents joined her there for a holiday. Mother fell in love with the Island and as the local doctor wanted to retire, she persuaded my father to buy the practice. Figure 1: Laxey Wheel In those days a medical practice was an asset which did indeed have to be bought. The average young man wishing to settle down as a general practitioner would not have the ready means to buy his practice outright. He would have to buy it 'out of income'. That is what my father did. My mother's mother died and we moved to a small house at Fairy Cottage. One of my earliest recollections is of an accident which took place there. The house was on the inside bend of a very bad corner. It was a beautiful, sunny Sunday afternoon and I was in the small front garden. Suddenly a motorcyclist came roaring, far too fast, round the corner, which of course he failed to negotiate, and man and bike ended sprawling in the road. I promptly crossed over to him. I still have a very clear mental picture of the event: of the sunshine, the blue sky, myself in a white dress looking down gravely at the man lying in the roadway with blood on his face. Three years old does seem a little young to begin touting for business but obviously I had no doubts. "Would you like to see the doctor?" I asked the young man, and told him that I would see to it. Fairy Cottage sounds a most romantic place and there may well be some folk reason for its name, but I am afraid I have never heard it. It was just a collection of a few houses and one or two shops and -1- presumably the area surrounding them. We did not stay there for very long, but soon moved again - this time to Glamorgan House in South Cape. From the front, Glamorgan House looked most imposing. It had a veranda upstairs and stone pillars at the front door. At the back, however, it was very dull with no embellishments whatsoever, and the view from the upstairs windows was of the Manx Electric Railway line which bordered the garden. My father always referred to the house as "Queen Elizabeth in front and Mary Ann behind." When we first moved there, there was no indoor lavatory or bathroom. Behind the house there was a 'backyard' with a coalshed, a washhouse and a 'tigh veg' - Manx for 'little house' - in our case, a two-seater privy! This was a very primitive affair. It consisted of a single wooden bench with two round holes. Behind and below the privy was a closed-in space to house the results of the calls of nature. Access to it could be obtained through a smaller door alongside the privy and also opening on to the backyard. This was necessary as the Parish Council employed a man to drive a horse and cart around the district for the purpose of emptying such places. We were only renting the house so the landlord had to be persuaded to install the essential amenities. He did so, but with extreme reluctance. His comment about such extravagance was that it had always been good enough for his grandfather, so he could not see why it was not good enough for the doctor. For me the house was a happy one. The garden was attractive to a child, full of trees and bushes which made lovely hiding places in games. It was built on a slope and from the front was approached by a longish drive which went right round to the back gate. This gate led to the South Cape Manx Electric Railway stop. The Railway, incidentally, was usually known as the Manx Electric or the M E R. Having a stop (it certainly was not a station) right outside the back gate was a great convenience. One could rush out at the last moment to go by train one stop down the line to Laxey, or in the opposite direction, to Douglas or any station on the way. Being a very young child, of course, I was not conscious at that time of such things. Unless I was accompanied by my mother I never went outside the gate. There was no need; for me the garden was more than -2- adequate. A few years later however, it proved insufficient for my young brother. At the age of two he disappeared from the garden, causing absolute panic. The search was on. But it was some time before he was found by a fisherman. There he was sitting on the harbour steps just above water level. It was a tidal harbour which emptied down to nothing but sludge when the tide went out. At full tide the water was very deep. It was full tide on that occasion. For me the garden provided plenty of entertainment and I was in my element in it. Because of the slope, the drive was bordered on one side at the front, by a bank, where the garden was on a higher level. On the other side, behind a hedge, there was what we called 'the Jungle' - a wilderness. No doubt it would be greatly admired by conservationists today. To get to the front door one left the drive and came up a few steps between two square concrete posts, each topped by a large concrete ball, to the front garden. This was the only part properly laid out with flower beds. It was my mother's domain. She loved flowers and always kept it looking very pretty. Inside the house, coming through the front door - past those stone pillars - and through the front porch and the inside front door, there was a wide hall. On one side at the front there was a dining room and on the other a sitting room. Behind the sitting room was the kitchen and behind the dining room another room that estate agents would no doubt, refer to as a 'third reception room'. In fact, this was my playroom and I loved it. It had a door leading into a lean-to greenhouse and so, out into the garden. It was in this room that the tree was housed at Christmas. It was always a lovely big tree, appearing to my small person almost to touch the ceiling. It would have real miniature candles on it, in little clip-on holders. These would be lit only on Christmas Day and only when my parents were present. Half way along, the hall was divided by the staircase which mounted from the centre to the half landing, thus leaving a passage on either side. Each of these passages had a door at the end leading first to the back porch and then to the back door. This in turn led to the backyard which stretched right across the width of the house. The yard had a solid gate at either end. Such an 'embarras de richesse' by way of -3- gates and doors produced an endless, exciting variety of hiding places in young people's games. In summer, my father grew tomatoes in the greenhouse. Well, I am not sure that in fact he did grow them himself, but they were always regarded as his bit of gardening. He was most particular about his hands; he maintained that as a doctor he could not afford to let them become rough or calloused as it would not be fair to a patient who needed an examination. Whenever he washed his hands, as well as soap he used glycerine. I am quite sure that he genuinely held this opinion and he undoubtedly kept his hands in beautifully smooth condition. I suspect however, that it was also convenient. When I was older, I remember, the whole family used to clean the car - except my father. From an early age I was interested in the tomatoes. I soon learnt which shoots had to be removed and enjoyed pinching them out. It was exciting too, to watch the fruit ripening and to be allowed to pick tomatoes straight from the plant. Anyone who grows his own would agree that they certainly do taste decidedly nicer when they are as fresh as that. There was no electricity in the area at that time. The cooking was done by means of the kitchen range - a large fire which could be closed in and which had ovens at the side. This was fine in the winter but rather overpowering in summer. It also had to be cleaned out and relit every day, and no doubt consumed vast quantities of coal. The coal was delivered in sacks which the coalman would carry in on his back and empty in the coalhouse. There was no light inside except for what was supplied by a small window and through the door. There was always a spade standing against the wall and this was used to fill coal scuttles and buckets for the house. Light inside the house was supplied by tall oil lamps which my mother used to fill. In the evening then, she would light them. I thought the lamps were beautiful with attractive, colourful bases, glass chimneys and globes which went over the top. Later on, mother acquired an oil cooker - a Valor Perfection, I think it was called. This had an oven and about three burners on the top and a container at one end which had to be filled with oil. The latter was probably a nuisance but it was progress and was no doubt regarded as -4- very modern. For my part I loved the kitchen fire. The front was usually open and it always looked cosy, warm and comfortable. Toast was made at it. We had long toasting forks for the purpose; the bread was skewered on these and held close to the fire and in no time at all the toast was made. It was never hard but always beautifully soft, and, smothered with butter, it tasted delicious. In the months before Christmas, Mother would be busy making Christmas puddings, mincemeat and Christmas cake. Everyone had to take a turn to stir the puddings and at the same time make a wish. I cannot recall what tartaric acid was used for, but I do remember standing at the big kitchen table, my head barely reaching over the top and solemnly repeating my version of it: tar-ty-di-gastic! Because of my father's profession the house was never left empty. He was insistent that there must at all times be someone there in case of an emergency. His surgery was in Laxey village, not in the house, but of course there were occasions when people would call at the house looking for him. Mother, being a nurse, could at times be helpful too, with maybe, first aid, bandaging or even reassurance. A really bad emergency did once occur not very far from us. There was a place about half a mile away, between South Cape and Fairy Cottage where the Manx Electric Railway crossed the road. Here it was that a bad accident occurred involving a train. My father, of course, rushed there at once to do what he could for the injured. One woman, unfortunately, was trapped by her leg in the wreckage and could not be freed and it upset him greatly that her leg had to be amputated. In my young days there was no television and even radio was in its infancy and played no great part in our lives. My father however was always interested in what was happening in the world. he had his radio set, his wireless as we then knew it, and loved listening to the news. The set was powered by very large batteries which, when they ran down, had to be taken to a shop in the village to be recharged. My mother had a maid to help with the housework. This was particularly useful, in that it meant that she was not obliged at all times to be in the house, so to speak, on call. She had always been athletic and enjoyed sports. She still played hockey and later on took up golf. Having a maid in the house ensured that at least she could get out and also could safely leave me at home. -5- She loved animals and we were never without at least one dog and one Manx cat - sometimes more. She was not a patient woman but she had endless patience with the animals. If they were sick she would be quite prepared to sit up all night with them. I seem to remember that when they were convalescing she would hand-feed them calves foot jelly. Her feeling for animals is perhaps not surprising, for her own mother had been exactly the same. Mother once told me how her mother had been given a gift of three live ducks which were intended for the table. It never came to that however, because instead, they became family pets, Shem, Ham and Japheth, and lived long and happy lives! These traits do seem to come down the generations. Partly heredity maybe, but also the fact of having family pets and being taught to respect and love them. I am convinced that children can learn a great deal by having animals in their family circle. One of the most important things perhaps is responsibility. Learning to adopt a caring attitude to creatures weaker than themselves can lead to responsibility in other drections too. An added dimension is the sheer pleasure and actual friendship and loyalty that an animal imparts. One of the dogs we had was Paddy, a pure bred Kerry Blue. He was my father's idea. He had bought him and had him sent over from Ireland. We all loved Paddy but he was a menace. He couldn't stand any other dog and would pick a fight with one if he got the chance. My father often took him with him on his rounds, but each time, had to make sure that whilst he visited a patient, Paddy was safely in the car with locked doors. Paddy loved going to the beach, but because of his fighting habits, it became impossible to take him with us. There was a very amusing incident in Paddy's early days with us. Mother was in the water, swimming, when he decided she was in peril of her life. He swam out to her, caught her swimsuit in his mouth and made a gallant attempt to tow her to the shore. After she had resisted all his efforts, he gave up and, from then on, insisted on swimming in circles round her. It was, to say the least, somewhat restricting and therefore an additional reason for confining Paddy to the house when we went to the beach. On one occasion, however, Paddy defeated our efforts. He found an open window upstairs above the lean-to greenhouse and, fortunately -6- without injuring himself, escaped that way and joined us on the beach! Paddy was our first dog and he was of course, only a puppy when he came to us. At that time we had a female cat, Manx of course, called Chichi. Manx cats are a definite breed. They have hind legs longer than those of other cats and this seems to balance out the fact that they have no tail. Our Chichi was a most independent creature and strongly resented the canine invasion. Finding the puppy at the front door, she leapt on to his back digging in with all claws. Needless to say, he was terrified and raced round and round the front garden with Chichi riding him like a champion jockey. It needed my parents' combined efforts to separate them and rescue Paddy. However, Chichi and he came to terms later and at least learnt to tolerate each other. Paddy had many years with us but eventually developed a cancerous tumour in his hind quarters. When it became obvious that it would be unkind to keep him, my father, with great regret, injected him with an overdose of morphine. My mother's love of animals undoubtedly rubbed off on me. However they were not my only love. From as early as I can remember, I had a doll which, for some unknown reason, I called Peggy Diamond, and of course the inevitable teddy bear. I hated to be parted from them and naturally took them to bed with me. One of my early pleasures was a pair of yellow kid boots. They had black buttons right up the outside and had to be fastened with a buttonhook. I was immensely proud of them and, had it been possible, would no doubt have taken them to bed with me as well as Teddy and Peggy Diamond. The bed I remember from my early days was a forerunner of the modern cot. The ends and sides were made of thin rounded iron bars enamelled white and one side could be let down. Lying there one night, feeling hot and uncomfortable, I was kicking my legs about. Suddenly, in the semi darkness of the bedroom, I became conscious that my father was sitting quietly beside my cot. Immediately, I was filled with a wonderful sense of peace and reassurance and love. It was not a conscious thought. I just knew, without words, that I was loved and protected. I stopped struggling with the bed clothes and must have gone straight to sleep. -7- Those were happy days and they lasted till I was five years old. -8-