441KB - GST Distribution Review

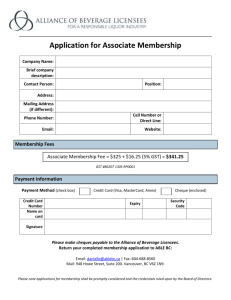

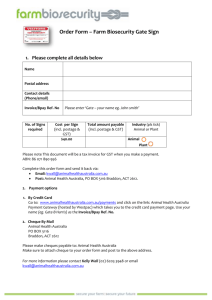

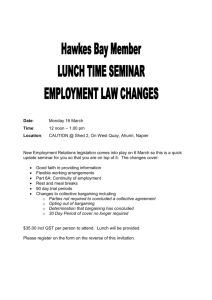

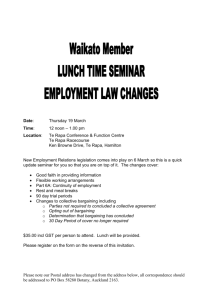

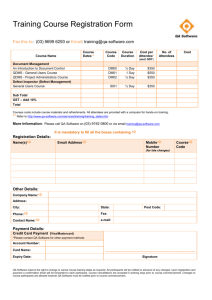

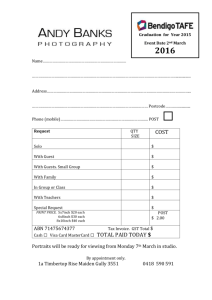

advertisement