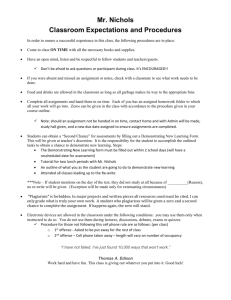

Attempt - heolddulaw

advertisement

ATTEMPT Essential reading: J Martin Criminal Law pages 59-66 The criminal law does not punish people for intending to commit a crime, but it recognises that conduct aimed at committing an offence may be just as blameworthy if it fails to achieve its purpose as if it had been successful. The difficulty for the law on attempts however, is to determine where to draw the line-how far does someone have to go towards committing an offence before his acts become criminal? Over the years the common law proposed various tests to answer this question but all have been problematic. Consequently much of the common law was replaced by the Criminal Attempts Act 1981. Actus Reus See s1 (1) for statutory definition of ‘attempt’. The question of whether an act is ‘more than merely preparatory ‘ is a question of fact for the jury to decide upon (or magistrates). The judge’s role is to consider whether there is enough evidence to leave this question to the jury but s4(3) of the Act states that the judge having concluded that there is, the issue should be left completely to the jury. What the jury have to ask themselves is whether D was simply preparing to commit the offence or whether D had done something that was more than merely preparatory to the commission of the full offence. Clearly there will be many cases where it is difficult to prove that D had crossed this line. Research the following cases: R v Campbell 1991 R v Gullefer 1987 Do you agree with these decisions? However the recent case of R v Dagnall 2003 may reflect a shift in the courts’ approach to the issue. On appeal D argued that his acts had not been more than merely preparatory, as he had not touched V in a sexual way. The appeal was rejected and the Court of Appeal pointed to the fact that the victim had been convinced that she was going to be raped. Attempting the Impossible Before the CAA 1981 impossibility was a defence to a charge of attempts- Haughton v Smith 1975- which effectively meant that if D reached into someone’s bag intending to steal a purse but found no purse in there they were not guilty of attempted theft. Many commentators found this ridiculous and now s1(2) of the Act states: ‘A person may be guilty of attempting to commit an offence to which this section 1 ATTEMPT applies even though the facts are such that the commission of the offence is impossible.’ Though generally viewed as more sensible than the position prior to the Act, this has caused some problems for the courts. Research the decisions in: Anderton v Ryan 1985 R v Shivpuri 1987 You may recall these cases from our studies on judicial precedent and the Practice Statement. As a result of Shivpuri a criminal attempt would be committed when Ben stabbed Chris intending to kill him not knowing that he had already died of a heart attack! The only case in which impossibility can now be a defence is where D attempts to commit what they think is an offence but which is not actually against the law. See the case of R v Taaffe 1984 Mens Rea The Act specifies that intention is required to commit the offence. Case law has made it clear that D can only be liable for an attempt if they act with the intention of committing the complete offence-recklessness as to the consequences of the act is not enough. This means that even if the offence attempted can be committed recklessly teher will be no liability for attempt unless intent is established- e.g. for most nonfatal offences recklessness is a sufficient mens rea but is not enough for a charge of attempting to commit any of them. In attempted murder the only intention that suffices for liability is intent to kill despite the fact that intent to cause GBH is sufficient for the full offence. For an attempt you must intend to commit the complete offence and the complete offence of murder requires the killing of a human being. See the case of R v Whybrow 1951 Where the definition of the main offence included circumstances, and recklessness as these circumstances is sufficient for that aspect of the mens rea then it will also be sufficient for an tempt to commit that offence (though intent will still be required for the rest of the mens rea). For example, liability for the offence of rape is imposed if a man intendeds to have sex with a man/woman knowing that they are not consenting or being reckless as to whether or not they are consenting. With attempted rape the absence of V’s consent 2 ATTEMPT is viewed as a circumstance of the offence and so long as D intends to have intercourse it will suffice that he is reckless as to the fact that V may not be consenting- he does not have to know for certain that there is no consent. Research the case of R v Khan and Others 1990 The point was confirmed in the case of AG’s Ref No.3 of 1992 Conditional Intention The concept of conditional intention has caused the courts problems in the past. This arises where a person intends to do something if a certain condition is satisfied (we examined this concept in burglary). The question is will this intent be sufficient to be the mens rea of an attempt. Doubt was raised in the case of R v Husseyn 1977 (research). The case caused considerable concern because it seemed to leave a big gap in the law. However in AG’s Ref Nos. 1 and 2 of 1979 it was said that the judgement in Husseyn could be explained by the fact that the charge had specified that the attempted theft was theft of the sub aqua equipment. If it had simply said e.g. that they intended to steal anything of value in the van then they could have been convicted. In conclusion, conditional intention is sufficient to impose liability for an attempt provided the charge is carefully worded. Criticism and Reform The limited approach taken to the meaning of more than merely preparatory has unfortunate implications for efforts at crime prevention and protecting the public. The police can still lawfully arrest anyone behaving as D did in Campbell on the basis that they have reasonable grounds for believing that he is about to commit an offence, but it appears that in order to secure a conviction for an attempt they would have to hold back until that person has actually entered the post office an approached the counter before arresting him. Clearly this may mean putting the post office and other people at unnecessary risk. The dangers of this approach may be seen in R v Geddes 1996 (research this case). The decision in Shivpuri has been criticised on the ground that it allows the law to punish people merely on account of their intentions. However it should be remembered that to be guilt of an attempt D must have done something which is more than merely preparatory and may in fact have tried very hard to commit an offence, failing to do so only through carelessness, chance or police intervention. In such cases incurring no liability would simple give potential offenders the opportunity to try harder net time! 3 ATTEMPT Some have argued that the maximum sentence for an attempt is too harsh. In certain US states for example the maximum that can be imposed is only half that of the main offence. Arguments in favour of the English position include the fact that D had the mens rea for the full offence and may be equally dangerous. The academic Becker argues that whether an offence is committed or merely attempted the same type of harm can be caused: disruption to social stability. On the other hand another academic Brady has suggested that the harm is not the same and it does not justify the same sentence. In practice however the judge still has discretion and most of the time judges choose to impose a lower sentence for an attempt. In the US a defence of withdrawal is widely accepted. This allows D to avoid liability if he voluntarily chooses not to go on and carry out the offence. At the moment in England this defence is available to accomplices but not to those charged with attempts. This means that once a person has done something that is more than merely preparatory they might just as well carry on and finish the job since stopping at that point will not necessarily reduce their liability. The Law Commission is opposed to a defence of withdrawal arguing that the issue can be left to mitigation in sentencing. 4