Dr - Lyme Association of Greater Kansas City

advertisement

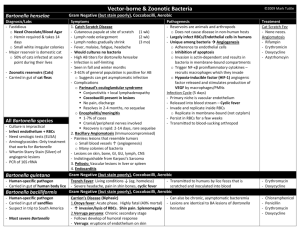

Lyme Association of Greater Kansas City, Inc. P.O. Box 25853, Overland Park, KS 66225 913-438-5963 (GET-LYME) Lymefight@aol.com www.Lymefight.info DVD's of Dr. Brewer's presentation are available by sending a check for $7 made payable to "Lyme Association" to the address above. "Tick-Borne Diseases and Coinfections" Dr. Joseph Brewer, M.D. May 25, 2006 Summarized by Kathy White, Secretary, Lyme Association of Greater Kansas City, Inc. Dr. Joseph Brewer is a doctor of Internal Medicine and Infectious Diseases. His website is www.plazamedicine.com. He spoke about tick-borne diseases at a meeting of the Lyme Association of Greater Kansas City at St. Joseph Medical Center in Kansas City, Missouri on May 25, 2006. He said the following: "Coinfection" means 2 or more pathogens acquired from tick exposure. Common tick-borne pathogens include Borrelia burgorferi (Bb), which causes Lyme disease; ehrlichia; anaplasma (similar to ehrlichia); rickettsia, which causes Rocky Mountain spotted fever; babesia (similar to malaria); bartonella (includes cat scratch disease); and mycoplasma. Infections with tick-borne diseases may or may not cause symptoms. These diseases may lie dormant and cause symptoms later. Each pathogen can produce illness in certain people. The most fatal tick-borne diseases are Rocky Mountain spotted fever and ehrlichiosis. There are places in the Northeast where 90-95% of the ticks carry Lyme disease. There are 3 major tick species in the U.S. and the world: Ixodes (includes deer ticks), Amblyomma (includes Amblyomma americanum – lone star ticks), and Dermacentor (includes Dermacentor variabilis – American dog ticks). Although Ixodes scapularis ticks are called deer ticks, other ticks also feed on deer. Ixodes scapularis ticks are prevalent in the Northeast. There are some in Missouri, but lone star ticks are far more common here and are the predominant ticks in the central and southern states. Ixodes pacificus ticks are prevalent on the West Coast. Adult Ixodes ticks have black legs. Lone star and deer tick nymphs have light brown translucent legs. American dog ticks are larger than lone star and deer ticks. RESEARCH STUDIES Probably the best study of diseases in ticks took place in New Jersey. ["Prevalence of Borrelia burgdorferi, Bartonella spp., Babesia microti, and Anaplasma phagocytophilia in Ixodes scapularis ticks collected in northern New Jersey," M. Adelson, R. Rao, T. Tilton, K.Cabets., E. Eskow, L.Fein, J. Occi, & E. Mordechai. J Clin Microbiol., 2004 June 42;6:2799-2081]. Researchers randomly collected a large number of ticks from various parts of NJ and tested them at Medical Diagnostic Laboratories (MDL) in N. J. They found: Bb (the cause of Lyme) in 33.6% of ticks; bartonella in 34.5%; babesia in 8.4%; anaplasma in 1.9%, and none of these diseases in 54.2%. Thus, almost half of the ticks were carrying a disease. Although Lyme disease is considered by far the most prevalent tick-borne disease in the nation and the world, there were slightly more ticks carrying bartonella than Lyme (34.5% compared to 33.6%). Bartonella plus Lyme were found in 8.4% of the ticks. About 14% of the ticks were infected with 2 or more diseases. Of these, almost 2% were carrying 3 diseases. 2 Veterinarians have published more research on coinfections than doctors. Researchers at the veterinary school at the University of North Carolina studied 27 sick hounds in a kennel [“Coinfection with multiple tick-borne pathogens in a Walker Hound kennel in North Carolina.” Kordick SK, et. al., J Clin Microbiol 1999 Aug;37(8):2631-8. PubMed ID 10405413]. All the dogs were given a blood test for antibodies. Antibody tests indicate prior exposure but not necessarily active infection. All 27 dogs were positive for at least one tick-borne disease: 26 were positive for ehrlichia, several species; 16 Babesia canis (dog strain); 25 bartonella, mostly Bartonella vinsonii (a strain that infects dogs); and 22 had antibodies to rickettsia. All 27 dogs were also given a PCR (polymerase chain reaction) test, which detects DNA of pathogens in the bloodstream. PCR is the gold standard in medicine, because it detects active infection, not just prior exposure. The PCR testing revealed: 15 dogs had active Ehrlichia canis (dog strain); 9 Ehrlichia chaffeensis; 8 Ehrlichia ewingii; 20 rickettsia; 16 bartonella; and 7 had Babesia canis. All 27 dogs were sick. Over half had bartonella and were still sick with it. Ehrlichia chaffeensis is the strain of ehrlichia common in Missouri and nearby states. It has caused several deaths in humans around here. There were 23 owners of the dogs who agreed to be tested. The owners were all healthy and without symptoms, although about 1/3 had antibodies to diseases similar to what the dogs had: 8 owners were positive for Bartonella henselae (cat scratch disease); 1 positive for ehrlichiosis; and 1 positive for rickettsia. Martin Fried, MD, a pediatric gastroenterologist affiliated with a major University in New York, and fellow researchers published a study, "Infections of the GI tract in children and adolescents" [Practical Gastroenterology, Nov. 2004]. They studied 81 children and teenagers with chronic intestinal problems that persisted for a long time. Almost all the children had known prior exposure to ticks. The doctors biopsied inflamed tissues and had them tested for tick-borne diseases by PCR at the MDL lab in New Jersey. The researchers found that tick-borne diseases can cause lots of GI (gastro-intestinal) problems: nausea, vomiting, abdominal pain, diarrhea, and bloody diarrhea. Of the 81 children tested: 35 had Bartonella henselae; 24 Mycoplasma fermentans; 14 Helicobacter pylori (believed to cause ulcers); and 13 had Bb, which causes Lyme disease. Of those with only one tick-borne disease: 12 had bartonella; 6 mycoplasma; and 3 Bb. The most common disease was Bartonella henselae (cat scratch disease). Of the children with coinfections: 10 had bartonella + mycoplasma; 6 Bb + bartonella; 2 Bb + mycoplasma; and 2 had 3 coinfections, Bb + bartonella + mycoplasma. Although these other diseases can coexist with Lyme, they may not always cause symptoms. We don't know. BABESIA Babesiosis is caused by babesia, a protozoan similar to the protozoan that causes malaria. Babesia is transmitted by ticks and was the first pathogen found to cause a coinfection with Lyme disease. Like malaria, babesia protozoans infect red blood cells and can survive indefinitely in the cells. There are over 100 different species of babesia that infect mammals, birds, and humans. Babesia microti is by far the most common strain in the U.S., transmitted almost entirely by Ixodes scapularis ticks, mostly in the Northeast and Upper Midwest. Babesiosis causes severe illness in people without a spleen, and most die. (The spleen removes old and infected red blood cells from the bloodstream. Sometimes a spleen is removed it if is damaged by an injury, such as a car accident.) Babesia divergens is the strain commonly found in Europe, mostly in people without a spleen. A different strain was discovered in 1991 in the state of Washington, called WA-1. A young farmer in the state who had tick bites on his arm got sick from the disease, even though he had a 3 spleen. Another strain, Babesia MO-1, was discovered in 1991 in Missouri in an elderly farmer who had had a lot of tick bites and didn't have a spleen. He died from the illness. Ticks on his farm were tested and found to have Babesia MO-1. Almost all cases of babesia are in people who didn't know they had a tick bite. Thousands of people in California test positive for the WA1 strain of babesia without having any symptoms. Babesia lives inside blood cells and could pose a problem for blood banks. Diagosis and Treatment Babesia can be diagnosed by antibody testing or PCR to detect DNA of the protozoan. Since it is not caused by a bacterium, regular antibiotics for Lyme disease don't work. Azithromycin (Zithromax) is used, but it doesn't work by itself. Zithromax is used with Mepron (atovaquone), an anti-malarial drug. The traditional treatment is clindamycin and quinine, which is inexpensive, but the quinine has bad side effects. Quinine is also used for malaria. Zithromax and Mepron are expensive, but this protocol works quite well, with few side effects. A study by Dr. P.J. Krause and associates, "Atovaquone and Azithromycin for the Treatment of Babesiosis", [NEJM, 2000 Nov 16;343(20):1454-8. PMID 11078770] described the effectiveness of azithromycin with Mepron. He studied people with Babesia microti, mostly in the Massachusetts area. His patients had: fever, sweats, chills, fatigue, achy muscles, nausea, vomiting, poor appetite, headaches, stiff neck, joint pain, joint swelling, and emotional lability. It is interesting to note that joint pain and swelling were symptoms, since these patients were believed to have babesia alone, without Lyme disease. The following babesia symptoms have been described in people without a spleen: fever (common), sweats, chills, fatigue, malaise (feeling ill), achy muscles, nausea, abdominal pain, anemia, and neuro-psychiatric symptoms. Veterinary literature describes chronic persistent babesiosis. It is somewhat difficult to treat. Dogs can become scraggly, and some die. Chronic infection with or without symptoms can occur in dogs, horses, cattle, and humans. People can test positive without getting symptoms. In the Northeast, 10% to 32% of Lyme patients also have babesia, especially in Connecticut and Massachusetts. They are sicker and have more flu-like symptoms than Lyme patients without babesia. In a study by Dr. P.J. Krause and associates, "Persistent parasitemia after acute babesiosis" [NEJM 1998 July 16;339(3);160-5], symptoms in some people persisted for 2 or more years. Dr. Edwin Masters, MD, a family practice doctor who treated tick-borne diseases in Cape Girardeau, MO, reported on his research at the EICS (Emerging Infections in the Central States) conference held in November, 2004 in Kansas City. He saved a tube of blood from over 150 patients who had a bull's-eye rash and sent it to Harvard, the world's leading babesia experts. All the blood samples were tested for Babesia divergens, the strain in Europe, because it is very similar to the MO-1 strain. (The CDC had previously found that the DNA of both strains was very similar, 99.2%.) There is no test for the MO-1 strain, but Harvard has a research test for it. MO1 is not much like Babesia microti and is not likely to show up on standard babesia tests. The testing at Harvard found that 2 to 4% of Dr. Masters' samples were positive for Babesia divergens antibodies. Therefore, Lyme disease patients in the Cape Girardeau area had about a 3% chance for a coinfection with babesia. Cottontail rabbits are probably the primary carriers of the disease. Dr. Masters found over 100 ticks on a cottontail rabbit. 4 EHRLICHIA / ANAPLASMA Until recently, anaplasmosis was called human granulocytic ehrlichiosis (HGE). It's now called human granulocytic anaplasmosis (HGA). The genus has been split it into 2 types, anaplasma and ehrlichia. Anaplasma, which is carried by Ixodes ticks, is not common in Missouri. It occurs mostly in the Northeast, Upper Midwest, and Pacific Northwest, where Ixodes ticks are prevalent. [Secretary’s comment: There have been reported cases of anaplasmosis in Missouri and Kansas since this speech was made.] There are Ixodes scapularis ticks in Missouri, but lone star ticks are much more common here. Lone star ticks and American dog ticks transmit Ehrlichia chaffeensis, the organism which causes human monocytic ehrlichiosis (HME). Ehrlichia chaffeensis is common in the Midwest and South. It was named Ehrlichia chaffeensis because the first reported case in a human was in a soldier at Fort Chaffee in Arkansas. Ehrlichiosis is an acute illness with a mortality rate of 1-5% (up to one in 20 people) if untreated. Ehrlichiosis symptoms are: fever, chills, headache, achy muscles, and sometimes bizarre neurological symptoms. Antibody tests aren't useful during the acute illness, because it can take several weeks for antibodies to develop, and it takes awhile to get the results back. The PCR test also takes a long time to get the results, and the patient can be dead by then. Instead, the physician should look at blood count and liver enzymes and begin treatment based on clinical judgment. Laboratory signs include decreased white blood cells, low platelet count, and elevated liver enzymes. If a person has a summer flu with a fever of 103 degrees, ehrlichiosis should be considered if there has been any possibility of tick exposure. Dr. Brewer has seen about 100 cases of ehrlichiosis. People come in very sick, with fevers of about 104 degrees. A few came to the hospital too late and died. Dr. Brewer has seen one hospitalized patient who tested positive for both ehrlichiosis and Lyme disease. He has seen a few patients who may have been coinfected with Lyme disease and Rocky Mountain spotted fever. Most people with coinfections of Lyme disease and ehrlichiosis probably have an acute illness of both diseases. In the Northeast, anaplasma (cousin to ehrlichiosis) represents1-4% of total coinfections, less common than babesia and much less than bartonella. Treatment Doxycycline is the recommended treatment [even for children], since most other antibiotics don't work for ehrlichiosis. Doxycycline is the only antibiotic that has been studied that works. It can make people start feeling better in just one day. [Secretary's comment: The CDC website, www.CDC.gov, gives dosage information for children. It says Rifampin has been used successfully in a few pregnant women. Doxycycline and other tetracyclines are not recommended during pregnancy.] BARTONELLA There are many strains of bartonella. It is common and world-wide and infects many kinds of ticks. Bartonella was originally described by Barton in 1909. It is such a tiny bacterium that it is called gram-negative. It infects red blood cells and probably also white blood cells and other cells. It can persist in cells indefinitely. In animals, it can cause persistent infection in a susceptible host, and it can probably also be chronic in humans. However, animals and humans can be chronic carriers of the disease without getting symptoms. Most of our information is from veterinary literature. It infects a wide variety of animals and has been found in dogs, cats, coyotes, cattle, horses, rabbits, deer, bobcats, rodents, and many other animals. There were over 20 strains of bartonella described by the year 2004. About half of those were discovered between 2000-2004, so a new strain gets discovered every few months. At that rate, 5 in 10 years we may know of 30 or 40 strains. We know at least 10 strains infect humans. Humans can get Bartonella henselae, B. quintana (trench fever), and some other strains. Bartonella can be transmitted by ticks, fleas, lice, mites, sand flies, deer flies, and house flies. It has just recently been discovered that ticks are transmitting the disease. In New Jersey, 34.5% of deer ticks (over 1/3) were found to be carrying Bartonella henselae (cat scratch disease). They weren't looking for the other strains. In California, a study found that 19.2% of Ixodes pacificus ticks carried Bartonella henselae [“Molecular evidence of Bartonella spp. in questing adult Ixodes pacificus ticks in California,” C.C. Chang et. al., J Clin Microbiol., April, 2001;39(4); p.1221-6, PMID 11283031]. At least 5 different strains of bartonella were found in the California ticks. In the Netherlands, 70% of Ixodes ricinus ticks found on deer were carrying bartonella, several different strains. Cat scratch disease can infect dogs. People can get the disease from the bite or scratch of a cat as well as from ticks. Cats get it from fleas from other cats or animals. Infected cats don't get sick. In humans, the disease travels through the lymph channels and causes swollen lymph nodes, fever and illness. The symptoms of Bartonella henselae (cat scratch disease) are: swollen lymph nodes, fever, endocarditis, retinitis, seizures (sometimes), and bizarre neurological symptoms (sometimes). If you have a healthy immune system and get only bartonella, without coinfections, you may get rid of the disease or carry the disease without becoming ill. There are a serology (blood) antibody test and a PCR test for Bartonella henselae, but there are no tests for the other strains. B. henselae is common in the Northeast, but in this part of the country other strains may be more common. Dr. Brewer has had a few patients that tested positive, but more people test positive back East. We could have many bartonella coinfections here, with other strains. We don’t know. You can have bartonella even if your test is negative, because you may have another strain. Veterinary schools can test dogs for several strains of bartonella. Eugene Eskow, M.D., an internist, and fellow researchers published a paper in the Archives of Neurology in 2001, titled "Concurrent infection of the central nervous system by Borrelia burgdorferi and Bartonella henselae" [2001;58:1357-1363]. Dr. Eskow studied patients who continued to have chronic Lyme disease despite treatment. He tested them for bartonella henselae. They all tested positive for Lyme and bartonella by antibody testing and PCR. The researchers concluded that people with chronic Lyme disease should be evaluated for B. henselae. The patients with Lyme and bartonella had the following symptoms: headache (about 80% of patients), fatigue (100% of patients), arthralgia (joint pain) (most patients), fever (about 1/3 of patients), poor sleep, dizziness, depression, confusion, decreased attention span, and decreased concentration (common). Treatment Symptoms persisted despite treatment for Lyme disease. When antibiotics were changed around, it didn't help consistently. Different people got better with different antibiotics. Nothing helped them all. When they got better, the bacteria disappeared from their blood and spinal fluid, and their symptoms got a lot better. One person who didn't respond to Rocephin got better on Doxycycline. Some who didn't respond to Doxycycline got better on Claforan. Some got better with Zithromax. We don't know why reponses vary. Treatment for bartonella "is a mess right now." Cat scratch disease was long thought to be a virus because it doesn't respond to antibiotics. Now that it is known to be a bacterium, antibiotics are being tried but don't work very 6 well. The bacterium responds to many antibiotics in a test tube, but the antibiotics don't work very well in the human body. No specialist knows how to treat bartonella yet. The following drugs work in a test tube: cephalosporins (Rocephin, Claforan), Doxycycline, Biaxin, Zithromax, Clindamycin, Rifampin, Levaquin, and probably Cipro and others. Dr. Joseph Burrascano made a presentation about coinfections at the October, 2005 ILADS (International Lyme and Associated Diseases Society) meeting. He thinks that bartonella may be more common than Lyme disease. Dr. Burrascano has had the best results treating bartonella with levofloxacin (Levaquin), although it doesn't work for Lyme disease. His patients with bartonella had a poor response to Zithromax and clarithromycin (Biaxin), and a fair response to Doxycycline and Rocephin. You can't use levofloxacin very long because it makes joints ache, even in just 12 days. MYCOPLASMA Mycoplasma is a bacterium that has no cell wall. It lives inside other cells. It can over-activate the immune system or suppress it. It occurs in people with AIDS, CFS (chronic fatigue syndrome), and Gulf War syndrome. Mycoplasma fermentans has been found in Ixodes scapularis (deer) ticks in New Jersey. Researchers at Medical Diagnostic Laboratories (MDL) in New Jersey studied deer ticks for various tick-borne diseases in 2004. They tested a few of the ticks for Mycoplasma fermentans, and 11% of the ticks were positive, according to MDL data from 2004. This information about mycoplasma was not published, because it was such a small sample of ticks. They are doing more research on mycoplasma now, using more ticks. Dr. Eugene Eskow, M.D., a doctor of Internal Medicine in NJ, studied 230 ill patients who came to his office after a tick bite believing they had Lyme disease. He had their blood tested at MDL by PCR testing to detect DNA for Lyme, other tick-borne diseases, and Mycoplasma fermentans. He also did a Western blot test for Lyme. A large number of the patients had Lyme disease; 40 of the 230 patients (17%) had Mycoplasma fermentans; and 24 of the 230 patients (10.4%) had Mycoplasma fermentans only, with no Lyme. Mycoplasma and Borrelia burgdorferi (Lyme disease) were the most common coinfections. Dr. Eskow and associates studied 7 of those who had Mycoplasma fermentans only, with no coinfections, and described their symptoms in detail in a paper published in the Journal of Clinical Rheumatology in April, 2003, "Evidence for disseminated Mycoplasma fermentans in New Jersey residents with antecedent tick attachment and subsequent musculoskeletal symptoms" [9;2: pp.77-87]. None of these patients had an EM rash or a postive serology test for Lyme disease. They all tested positive for Mycoplasma fermentans. After 14 days of the antibiotic Levaquin, they all got better, and their blood no longer tested positive for mycoplasma DNA. The patients who had only mycoplasma had these symptoms: fatigue (100% of patients), fever, joint pain (some also had swelling), myalgia (muscle pain), insomnia, headache, anxiety, emotional lability, poor memory, poor concentration, decreased attention, and confusion. Those who were high school students had the following effects: couldn't think well in school, too ill to attend school, spending 20 hours out of 24 in bed. All got better with 14 days of Levaquin, and their blood no longer tested positive for mycoplasma DNA. The girl who had been unable to attend high school was back in school within a month. Diagnosis Mycoplasma and other tick-borne diseases don't grow well in culture. It's easy to grow strep or staph infections in culture, but a culture test isn't as useful for the tick-borne diseases. The MDL lab in NJ has a mycoplasma serology (blood) antibody test, and a PCR test to detect DNA. Dr. Brewer has sent blood there to be tested, but none of his patients have tested positive yet. 7 Perhaps something happens to the blood during shipment to New Jersey, or perhaps we don't have as much mycoplasma here. Dr. Brewer has some patients who came to him with a previous positive test for mycoplasma. Treatment Previous studies on treating mycoplasma, including studies of people with Gulf War syndrome who had mycoplasma, were primarily with Doxycycline, and also with azithromycin (Zithromax), clarithromycin (Biaxin), and fluoroquinolones (levafloxacin, ciprofloxacin, etc.). Doxycycline, azithromycin, and clarithromycin inhibited the growth of mycoplasma but didn't kill it. In a test tube, fluoroquinolones kill mycoplasma, but the other drugs don't; they just inhibit its growth. With Lyme disease, also, a lot of drugs inhibit the growth of the bacteria but don't kill it. In Dr. Eskow's 2003 study, he found Levaquin (levofloxacin, a fluoroquinolone) for 14 days to be very effective for mycoplasma. Every one of his mycoplasma patients got better with Levaquin. Some people may need more than 14 days of treatment. Dr. Eskow used a longer course of treatment with Levaquin for certain patients, but he tries to keep the treatment short, because fluoroquinolones can be harmful to tendons and can cause the Achilles tendon to rupture, and fluoroquinolones also cause joint pain and can make the joint pain of people coinfected with Lyme disease much worse. Cipro (ciprofloxacin), another fluoroquinolone, is also very effective for mycoplasma, but it has these same side effects. Relapses may be possible after treatment with fluoroquinolones, but we don't know the relapse rate. There is a high relapse rate with Docycycline. In the Gulf War syndrome studies, patients who had mycoplasma were treated with Doxycycline and needed months to several years of treatment. Dr. Brewer believes mycoplasma should be treated with fluoroquinolones, since those drugs are effective. WHAT WE KNOW ABOUT COINFECTIONS Babesia microti, Mycoplasma fermentans, and Bartonella henselae are coinfections with Lyme. Bartonella henselae (cat scratch disease) can be a cause of lack of response to therapy for Lyme disease. Ehrlichia and anaplasma cause acute illness and can be a coinfection with Lyme, probably in only 1% or fewer Lyme cases. According to the 2004 study of ticks in New Jersey, only 1.9% of ticks were carrying anaplasma, and slightly fewer than 1% of ticks carrying Bb were coinfected with anaplasma. WHAT WE DON'T KNOW ABOUT COINFECTIONS Whether ehrlichiosis and anaplasmosis can sometimes be chronic in humans. They are chronic in animals. Ehrlichia canis is chronic in dogs. What the role is of the other babesia strains that are not Babesia microti, such as MO-1. A test for MO-1 may be coming in the next few years. What the role is of other strains of bartonella and mycoplasma. We don't have tests for most strains of bartonella and mycoplasma. We have a test for Bartonella henselae, the cat scratch strain, but not the other 19 strains of bartonella that have been discovered so far. WHEN SHOULD A COINFECTION BE SUSPECTED? When there is a poor response to effective Lyme disease treatment. Poor response doesn't always mean a coinfection, but the possibility should be considered. Lyme is difficult to treat for many reasons, including altered forms, cyst form, intracellular forms, and brain infection. When there has been extensive tick exposure. The more tick bites a person has, the higher the risk of getting one or more pathogens. 8 When a person has certain symptoms: flu-like symptoms, such as fever, chills, GI symptoms, possibly others. All these diseases cause flu-like symptoms, so it's hard to distinguish the diseases based on symptoms. Better tests would make diagnosing these diseases a lot easier. We need good blood tests. SUMMARY The dog owners were carrying bartonella but weren't sick. The immune system may be an important factor in whether a person becomes ill. People who have had hundreds of tick bites may have a dormant disease that becomes activated when they become infected with Lyme. We know mycoplasma and Lyme disease can suppress the immune system. When a person gets these and other tick-borne diseases, one of them knocks out the immune system, and then the others become active. Lyme disease can cause profound immune system abnormalities. QUESTION AND ANSWER SESSION Dr. Brewer took questions from the audience. When asked about other modes of transmission, he said we know many insects carry bartonella. Bartonella is transmitted from one cat to another by cat fleas. Dog fleas can also carry bartonella. A study in California found that house flies can transmit bartonella to cattle. Ticks may be the only vectors of babesia. Ticks drink more blood than mosquitoes and other insects, and it may be that babesia needs a lot of blood to survive in. Babesia is substantially different from the organisms that cause the other diseases. We don’t know whether people can get Lyme disease from eating raw meat, but it might be possible, especially if eating undercooked deer meat. Cooking meat thoroughly at normal cooking temperatures kills all these disease organisms. The World Health Organization advises cooking chickens and wild birds to an internal temperature of 150 degrees to prevent bird flu. We have tests for Babesia microti, the strain in the Northeast, but not the babesia strain we have here. People here test negative. There is a test for the cat scratch strain of bartonella, which is transmitted by ticks in the Northeast, but no test for the other strains. We have a test for Mycoplasma fermentans, but not for the other strains. A person can have negative tests for all these diseases and still be infected with a different strain. We do have very good tests for ehrlichiosis. Antibody testing can tell if you did have it, if you get a positive IgG. When asked about Lyme disease testing, Dr. Brewer recemmended IGeneX Laboratories in California. [See www.igenex.com.] Lyme disease can be cured and gone for a few years and then come back as a relapse. Rocky Mountain spotted fever (RMSF) is here, but it is much less common than ehrlichia. With RMSF, you have a pretty good chance of dying. Doxycycline is the treatment, even for children, for RMSF. Children shouldn't normally be given Doxycycline. All the antibiotics used for adults except the tetracyclines (such as Doxycycline) can be used to treat Lyme disease in children. If a child has lots of tick bites, watch and give Doxycyline if a high fever develops. For adults, Doxycycline is the drug of choice for tick bites. Adults can have prophylactic treatment with Doxycycline after a tick bite. There is no published data proving that vitamin C infusions work for Lyme disease. Vitamin C kills cancer cells in a test tube and is being studied for cancer treatment at the University of Kansas Medical Center. It may work for infections and HIV. It is very safe, even at high doses. Insurance won't pay for it. Research is needed.