Report on existing foreign language and oral testing formats

advertisement

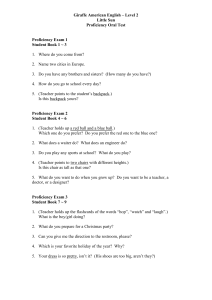

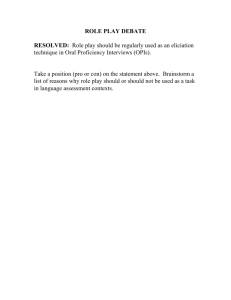

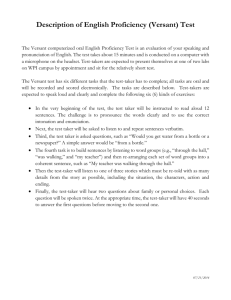

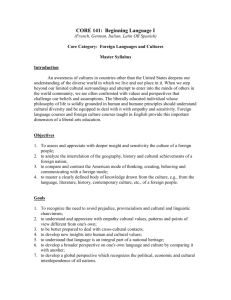

On the Way to Developing a MARTEL Plus Speaking Test Introduction Assessing linguistic competence in Maritime English adequately and reliably at internationally recognized levels has been set forth in recent years as a major issue because it reaches out equally to merchant marine officers, cadets and students, as well as Maritime English Training (MET) institutions, maritime administrations, ship owners, etc. Indeed, all the above mentioned parties have come to recognise the need of developing exam systems evaluating spoken competence [1] and conducting Maritime English oral tests to this effect. Furthermore, the necessity to ensure effective communication (in both written and oral form) in its diverse manifestations in various nautical and technical spheres has been explicitly expressed in the Manila amendments (2010) to the STCW Convention 1978/95. [2] The Testing Context The IMO requirements for English language competence needed for work in the maritime environment have been stipulated in SOLAS, Chapter 5 and the STCW convention and code. To sum them up, they can all be expressed as the ability to communicate: with other ships and coast stations with multilingual crews in a common language information relevant to the safety of life at sea , pollution prevention, etc. [3] The ISM Code, in addition, emphasizes on effective communication in the execution of crew’s duties which in practice is usually made in English. Based on feedback received from different parties and in response to the need of developing a more comprehensive process for the evaluation of oral competence, as raised in the 2010 IMO STW 41 meeting, the MARTEL Plus project set as one of its goals to embark on enhancing the speaking part of the MARTEL test of maritime English language proficiency. The latter was created under the EU Leonardo da Vinci funding stream, in combination with the Lifelong Learning Programme [4]. They envisaged this as a complement to the existing MarTEL standards, a two-tier system, including the current MARTEL speaking section plus a separate one to one oral examination [5]. Conducted with a qualified examiner/interlocutor it would allow for a structured interview to elicit performance, a greater reliability and a fair assessment of a candidate’s ability to speak English. The aims of this report are: - to review existing foreign language and oral testing formats, to compare them and find out the most suitable option for the new MarTEL Plus speaking test incorporating in it the specific oral capabilities required by the maritime industry - to report on developments made so far by the Bulgarian team. Research and Review of Some Existing English Oral Tests Instead of delving into the multitude of existing English oral tests, we chose to get familiar with only some of them pertinent to a particular target language use situation, namely RMIT English Language Test for Aviation (RELTA), Trinity Spoken English for Work (SEW), STANAG 6001 tests and the Oral Proficiency Interview (OPI). We selected them not only as tools providing proficiency rating scales for specific communication skills in a certain sphere of ESP but also as testing format types and compared them in terms of: - purpose - intended users - test takers - target language use situation - test format and task types - testing benchmark There have been some objective as well as subjective reasons for dwelling on these test formats. We chose RELTA as being a test developed for a professional domain with a stress on speaking. The RMIT English Language Test for Aviation (RELTA) is one of the tests developed to meet the International Civil Aviation Organization (ICAO) language proficiency requirements for testing. It is used to evaluate language proficiency of pilots and air traffic controllers for the six ICAO levels. The RELTA consists of a 25 minute speaking test and a 35 minute listening test, both completed on a computer. The RELTA is used to assess speaking and listening proficiency in both phraseology for routine communications, and plain English for non-routine and emergency communications in radiotelephony and face-to-face situations, as required by the ICAO Language Proficiency Requirements [6]. Our second choice was based on the contextualized non-native speaker environment the test format offers. The Trinity College of London Spoken English for Work (SEW) examination measures spoken English in a working context relevant to the chosen profession of the candidate. It is designed for anyone aged 16 and above who is already working or is preparing to enter the world of work. The exams benefit non-native speakers from any profession where English language proficiency is either a requirement or an opportunity for better career prospects and promotion. It is not sector-specific and can be applied across an organisation to all employees who need to speak English in their job. The test focuses on the speaking and listening skills used in everyday working environments. All of the tasks are contextualised around the world of work including a work-related telephone call between the candidate and the examiner. The assessment also takes into account a wide range of employment tasks, allowing each candidate to communicate about their individual work-related experiences. SEW is available from B1 to C1 in the Common European Framework of Reference for Languages (CEFR) [7]. The reasons for choosing the Bulgarian STANAG 6001 Speaking Section test format were purely subjective – all members of our team have had some personal involvement in developing and administering STANAG tests under the Partnership for Peace (PfP) programme. There is no official exam for the STANAG 6001 levels and countries which use the scale produce their own tests. The tests usually consist of four sections dedicated to the four major skills. The Speaking Section measures skills required in a multinational military environment on personal, public, and professional topics. The tests may be single-, bi- or multi-level and involve a variety of tasks to ensure that candidates can: - communicate in everyday social and routine workplace situations - participate effectively in formal & informal conversations - use the language with precision, accuracy, and fluency for all professional purposes, etc [8]. The Bulgarian team developed a multi-level test which in the long run proved to be the better choice. Last but not least, consideration was also given to the so-called Oral Proficiency Interview (OPI), as we have all been OPIed and it has given us the good experience to be “on the other side”. This test has the unique advantage of being a standardized method of measuring actual proficiency in language skills required to function in given life/job-related situations, as well as a testing tool with low risk of compromise. It is a test given to ascertain a person's English language, listening, comprehension and speaking skills in many U.S. government institutions and in use in some NATO countries with applications in both the business and educational world. The OPI is conducted via the telephone or face-to-face with one or two interlocutors and may be recorded in order to ensure an independent rating procedure. The OPI cycle consists of several stages: warm-up, level checks, probes, and wind-down. The role of the 'warm-up' is to put the interviewee at ease and to generate topics which can be explored later in the interview. The level checks allow the test-taker to demonstrate his/her ability to deal with tasks and contexts at a particular level. Level probes serve to determine ability to perform linguistic tasks at the next higher base level. The wind-down brings the interview to an end. Each interview may last from 20 to 40 minutes depending on the time needed to obtain a ratable speech sample involving multiple language functions, tasks and topics, yet inevitably following the same standardized procedure irrespective of the test taker’s level [9]. Appendix 1 represents in brief how the four test formats compare in terms of the criteria already mentioned above. What follows from our review is that existing English oral tests present candidates with tasks that resemble as closely as possible what people do with the language in real life performing a variety of language functions at the same time. The test-taker’s performance has to be spontaneous since in real life we rarely have the chance to prepare for what we want to say. Whether face-to-face, telephone or computer-delivered the testing method, test takers are evaluated in their use of language related to both routine and non-routine (unexpected or complicated) situations. Taking this into consideration we agreed that the MarTEL Speaking Test should differ from a large number of modern speaking exams that claim to assess candidates’ overall speaking ability in English for no specific purpose. Rather, it should aim at assessing the linguistic competence in Maritime English environment, incorporating maritime specialized and terminological vocabulary, but should refrain from testing professional competency. Moreover, it must differ from Marlin’s Test of Spoken English (TOSE) and the Test of Maritime English Competence (TOMEC). Therefore the MarTEL Speaking Test will uniquely address communications by being a ‘Maritime Test of English Language’ and not an ‘English Test of Maritime Knowledge’. [10] Research and Review of Existing Language Proficiency Descriptors and Frameworks In order to ensure that language proficiency is understood in similar terms and achievements can be compared in the European context, the Council of Europe has devised a common framework for teaching and assessment, which is called ‘The Common European Framework of Reference for Languages’, or CEFR for short. The CEFR, though not a testing tool proper, furnished us with some useful ideas pertinent to the maritime environment, like “the plurilingualism in response to European linguistic and cultural diversity”, the common reference levels needed “to fulfil the tasks … in the various domains of social existence”, the flexibility of “common reference levels”, “the various purposes of assessment”, etc. [11] The International Civil Aviation Organisation (ICAO) has established English language proficiency requirements for all pilots operating on international routes, and all air traffic controllers who communicate with foreign pilots. These standards require pilots and air traffic controllers to be able to communicate proficiently using both ICAO phraseology and plain English. Performance is graded on a 6-band scale (1 – 6) according to the following criteria: pronunciation, structure, vocabulary, fluency, comprehension, interactions. They reflect a similar target language situation and attempts have already been made on creating a test representative of it. [12] NATO Standard Agreement (STANAG) 6001 is an international military standard developed to measure general language proficiency of key personnel being prepared to take part in or actually participating in peacekeeping missions and performing various duties in NATO-led operations. There is no official exam for the STANAG 6001 levels and countries which use the scale produce their own tests. Test-takers are assigned levels on a band scale from 0 to 5, expressed by whole numbers. Borderline (plus) levels are also used for levels from 0 to 3. [8] Similar to it is the Interagency Language Roundtable (ILR) scale of oral proficiency which is usually employed when assessing an OPI. It is a set of descriptions of abilities to communicate in a language developed originally to assess the language proficiency of federal government and diplomatic personnel. This is a system of measuring language proficiency on a scale of 0 to 5. Proficiency level of 0 equates to no knowledge of a language, while the proficiency level of 5 equates to a highly educated foreigner or native speaker. Proficiency levels in excess of a whole number, but not reaching the next whole number are represented with the 'plus' sign, for example, a linguist who speaks at a near native level might be represented as having a 4+ level proficiency. [13] Outcome 1. As the Model course (3.17) on Maritime English presents us with the IMO requirements on use of Maritime English in professional context we derived a list of topics for our testing needs. They are divided into social exchanges, job-related and emergency types and broken down according to the CEFR levels. This is important because we believe that a variety of topics should be explored in the speaking test. Having prepared the list of topics we found that the list of routine topics progressively increases in contrast to non-routine ones and outweighs them. We consider this quite natural and typical of each proficiency level as they may be qualified "conversations in relevant situations" as referred to in the CEFR. (See Appendix 2.) 2. Following CEFR, each level in terms of topics should encompass those included in the lower levels but the expected output should be different based on the idea that it will be a global, multi-level test covering levels A1 through C1 for each MarTEL phase and specialty as agreed in Work Package (WP) 3. 3. There aren't many engineering-related topics in the Model Course so we think we should expand the list and make some contributions to it based on our teaching experience. This will provide engineers with equal opportunities to be tested fairly. 4. We find appropriate the idea of linking different phases of the MarTEL tests to test levels. However, if we have to associate a level with a position on-board, it would be better to assign minimum level requirements such as: Phase R – A2 Phase 1 –not less than B1 Phase 2 – B2 Phase 3 – B2 - C1 (to be confirmed at a later date possibly after piloting) Thus, when taking the test if a rating performs at B1 s/he will be assigned B1 in accordance with the rating scale and still be eligible for the rating position. On the other hand, if s/he performs at A1, the test will show that s/he has a very low level of oral English but will meet the requirements for the position of a rating. This specific information may be crucial for future employers. 5. Level C1 is not covered in the Model Course but we are of the opinion that senior officers take part in formal language communications. Besides C1 is a proof of the level of language needed to work at a managerial or professional level or to follow a course of academic study at university level. Therefore we strongly believe that this justifies the inclusion of C1 in the test specifications We find the topics suggested in Model Course 3.17, Core 2 suitable for B2 to be appropriate for C1 as well. C2 may not be applicable for the maritime domain especially for non-native speakers. Having consulted the CEFR [14], we found descriptors lacking C1 and C2 for performing some of the functions. Taking into consideration the multilingual crews as well as the different levels of English language competence on board ships, we decided that it would be irrelevant to expect a C2 performance in seafarers' routine duties. 6. The channel of communication should be face-to-face (involving a test-taker and an interlocutor), not computer-delivered no matter how tempting it might appear at this stage. This is the natural way of communication and enables the test-taker to demonstrate his/her linguistic abilities in real interaction in close to real life situations. Moreover, it provides sufficient evidence that the test-taker is able to participate fluently in real communicative events. 7. VHF communications including use of SMCP will not be tested as they are covered in other sections of the MarTEL test and given due attention. 8. The speaking grid has been designed and is under constant revision. It will hopefully serve as the basis for developing the two versions of the test specifications (for test-developers and for public use). It focuses on linguistic and pragmatic competence criteria as well as on interaction. We believe they incorporate the speaking assessment factors relevant to the context. As for sociolinguistic competence it should be given priority in the process of teaching rather than testing. 9. The general features of the test format are being discussed based on the conducted research. The issues of importance are the test length, number of sections, the number and type of tasks and the assessment criteria. The tasks will be set in a carefully designed context and will engage test takers in language performance in such a way that their contributions are not rehearsed or prepared in advance. The final outcome will be reflected in the test specifications. General Assumptions The following assumptions are based on research findings in the field of assessing languages for specific purposes (LSP). We considered them as a starting point in defining the conceptual framework of all documents and test materials we were tasked to develop. 1. There is a threshold language ability required before test-takers can make effective use of their background knowledge in a specific context of language use. 2. There should be a link between the theory of test development and the practice of selecting and using proper field specific materials in the process of designing valid and reliable LSP tests. 3. In the light of developing communicative tests the construct of specific purpose language ability is based on the interaction of two components: language knowledge and strategic competence. [15] General Considerations In our efforts to carry out the research into and the review of the existing test formats for testing oral production we had a few concerns to begin with. The first one was related to the description of some central features of the testing context and the test format. This was necessary to help provide the background of the kind of speaking to be assessed, i.e. construct specification [16]. In our discussions we were trying to identify what speaking means in the context of maritime English and the kinds of tasks incorporated in the test in order to test that kind of speaking. Research findings show that it is difficult to find suitable and novel tasks that test communicative ability alone and not intellectual capacity, educational and general knowledge or maturity and experience of life. In addition, the choice of the type of assessment is limited to construct based and task based where the latter is especially used in professional contexts as the scores give information about the examinees ability to deal with the demands of the situation. Researchers do not look at the two perspectives as ‘conflicting’ [17]. Therefore, combining elements of the two appeared to be the tool that would satisfy the needs of our particular context. We approached the test format and its elements using the definition in the Dictionary of Language Testing [18]. We focused on some of the elements of the test design namely the task types and the kinds of responses required of the test-takers. These two are of primary concern as the flexibility of the task frame guides or limits the response of the test-taker. Specialists in language testing distinguish between open-ended speaking tasks, structured and semistructured tasks. In the maritime context and for our particular needs we find the open-ended tasks very flexible in terms of language production and indication of speaking skills. The OPI, for example includes a number of open-ended tasks that are related to description, instruction, comparison, explanation, justification, prediction, decision. The structured speaking tasks cannot assess the unpredictable and creative elements of the speaking. The semi-structured tasks, reacting to situations, for example, tend to be used within a particular culture. Further on, the most common way of arranging the speaking tasks is the interview format. Its history dates back to the 1950s when it became a standard tool for testing speaking. Some of its advantages are: - it is realistic and resembles real life communication and interaction; - it is flexible, questions can be adapted to each individual test-taker’s performance; - it gives the interlocutor a lot of control over the interaction. This format has been viewed as very time-consuming. Another disadvantage could be the subjectivity of the assessment as the examiner might be influenced by the test-taker’s personality or communication style. This is one reason why there should be two examiners – one to conduct the interview and the other one to be the assessor. In this way the interlocutor will stay focused on the interaction process helping and encouraging the test-taker to demonstrate their best and carefully going through all stages and tasks of the interview. The assessor on the other hand, will be involved in evaluation and will remain focused on the testtaker’s performance. The final score will be discussed by both until an agreement is reached. A team of two examiners has been the most common practice in the testing community as it is believed to reduce the level of subjectivity. This implies that both examiners should have adequate training and qualification to use the format as a measurement instrument and provide fair testing conditions for each test-taker. Our second concern refers to ethics. Being fair to all test-takers is a major matter of interest for all test developers and examination boards. This is the reason why some formats come with the accompanying test materials, e.g. sample materials, preparation materials, etc. to provide conditions for fair testing. The EALTA Guidelines for Good Practice in Language Testing and Assessment was the document we used to make sure we were on the right track. It is our responsibility as test developers to become familiar and follow the general principles of good practice. There are also issues we need to clarify to ourselves before we begin our work on the test(s). For example, it is important for us to find answers to questions like: 1. Does the assessment purpose relate to the curriculum? 2. How appropriate are the assessment procedures to the learners/test-takers? 3. What efforts are to be made to ensure that the assessment results will be accurate and fair? 4. Will there be any preparatory materials? 5. Will markers/examiners be trained for each test administration? 6. Is the test intended to initiate change(s) in the current practice? 7. What evidence is there of the quality of the process followed to link tests and examinations to the Common European Framework? [19] To provide answers to these questions we should be engaged in discussions with the decision makers to ensure that they are aware of both good and bad practice. The third issue which is sometimes ignored is the washback (or backwash as used in the general education field) effect. The notion of `washback` refers to the influence that tests have on teaching and learning. Different aspects of influence have been discussed in different educational settings at different times in history due to the fact that testing is not an isolated event [20]. Washback studies investigate the impact of different types of tests on the content of teaching, teachers’ approaches to methodology and the reasons for their decisions to do what they do. Furthermore, researchers suggest that `high-stakes tests` would have more impact than lowstakes tests [21]. If we consider the new speaking test a high-stakes test, we should then be aware of factors such as the status of the subject, i.e. English within the curriculum, the prestige of the test, the nature of teaching materials, teacher experience and teacher training, teacher awareness of the nature of the test as they all would affect the amount and type of washback. New tests do not necessarily influence the curriculum in a positive way as changes do not happen overnight and teachers do not always feel ready to implement changes. In his study on the washback effect of the Revised Use of English Test, Lam concludes that it is not sufficient to change exams: “The challenge is to change the teaching culture, to open teachers` eyes to the possibilities of exploiting the exam to achieve positive and worthwhile educational goals” [22]. Whether intended or unintended the washback effects demonstrate the complexity of the phenomenon. One conclusion based on washback research findings is that there is a complex interaction between tests on one hand and language teachers, material writers and syllabus designers on the other hand and we should be aware of this. Conclusion This report was written to inform decision-makers about the progress made so far by the Bulgarian team. Some major research findings in the field of testing have been considered in making decisions about the development of the new test. The beginning has been set and there is a lot of work ahead of us. We hope we are on the right track. References 1. Logie Catherine Whose culture? The impact of language and culture on safety and compliance at sea Retrieved February 4-th 2011 from http://www.ukpandi.com/fileadmin/uploads/uk-pi/LP%20Documents/Industry%20Reports/ Alert/Alert14.pdf. 2. Subcommittee on Standards of Training and Watchkeeping, Report to the Maritime Safety Committee Retrieved February 24-th 2011 from http://www.uscg.mil/imo/stw/docs/stw41report.pdf. 3. STCW Code, Table A-II/1, Table A IV/2 4. www.martel.pro 5. http://www.plus.martel.pro/ 6. http://www.relta.org/ 7. http://www.trinitycollege.co.uk/site/?id=1521. 8. http://www.md.government.bg/bg/doc/zapovedi/2009/2009_OX626_STANAG_Spec_EN.pdf 9. http://www.dlielc.org/text_only/Language_Testing/opi_test.html. 10. Ziarati R, Ziarati M, Çalbaş B. Improving Safety at Sea and Ports by Developing Standards for Maritime English Retrieved on Feb 24 2011 from http://www.healert.org/documents/published/he00845.pdf. 11. Common European Framework of Reference for Languages: Learning, Teaching, Assessment (CEFR), CUP, 2001. 12. http://www.englishforaviation.com/ICAO-requirements.php 13. http://www.reference.com/browse/wiki/ILR_scale 14. Common European Framework of Reference for Languages: Learning, Teaching, Assessment (CEFR), CUP, 2001, pp 58-59. 15. Douglas, D. Assessing Languages for Specific Purposes, Cambridge Language Assessment series, Cambridge University Press, pp.30-36., 2000. 16. Luoma, S. Assessing Speaking, Cambridge Language Assessment Series, Cambridge University Press, 2004. 17. Luoma, S. Assessing Speaking, Cambridge Language assessment Series, Cambridge University Press, p.42, 2004. 18. Dictionary of Language Testing, Studies in Language testing 7, Cambridge University Press, 1999. 19. EALTA Guidelines for Good Language testing and Assessment www.ealta.eu.org/guidelines.htm. 20. Shohamy, E. The power of tests: The impact of language tests on teaching and learning. NFLC Occasional Paper. Washington, DC: National Foreign Language Center, 1993. 21. Alderson, J.C. and Wall, D. ‘Does Washback Exist?’ Applied Linguistics, 14(2): 115-29, 1993. 22. Lam, H.P. Methodology washback – an insider’s view. In D.Nunan, R.Berry, & V.Berry (Eds.), Bringing about change in Language Education: Proceedings of the International Language in Education Conference 1994 (83-102). Hong Kong: University of Hong Kong, 1994. Appendix 1 Criteria purpose RELTA To measure specific purpose language proficiency in aviation English SEW To measure spoken English in a working context for better career prospects and promotion intended users Air Navigation Service Providers, Aircraft Operators and National Regulatory Authorities Pilots, air traffic controllers, aeronautical station operators Prospective employers test takers target language use situation test format and task types testing benchmark Radiotelephony communications in air navigations and traffic control services/the aviation community Speaking and listening computer delivered test, Section 1, 2 test radiotelephony in phraseology and plain English, Section 3 interview ICAO rating scales STANAG 6001 To assess the overall English language proficiency (not professional competence) of military personnel for career selection and promotion NATO member states Ministries of Defence OPI To assess listening, comprehension and speaking skills for educational and employment purposes Non-native speakers already working or preparing to enter the world of work Non- sector-specific Military and civilian personnel in the armed forces Military students/staff and government agency officials Military-related context Life and job-related context Speaking and listening, role-play phone task (problem solving); topic discussion; presentation Speaking section – face-to-face structured interview involving various tasks – conversation, roleplay, information gathering task, topic discussion, etc. STANAG 6001 Language Proficiency Levels Face-to-face or telephone 3-phase interview containing a series of different tasks, topics, elicitation techniques, etc. CEFR Government institutions in the USA , Canada and other NATO countries Interagency Language Roundtable (ILR) Skill Level Descriptions