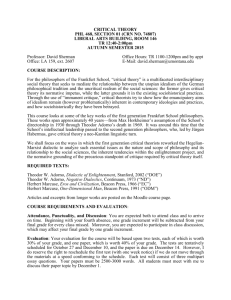

The Essential Marcuse - Simon Fraser University

advertisement