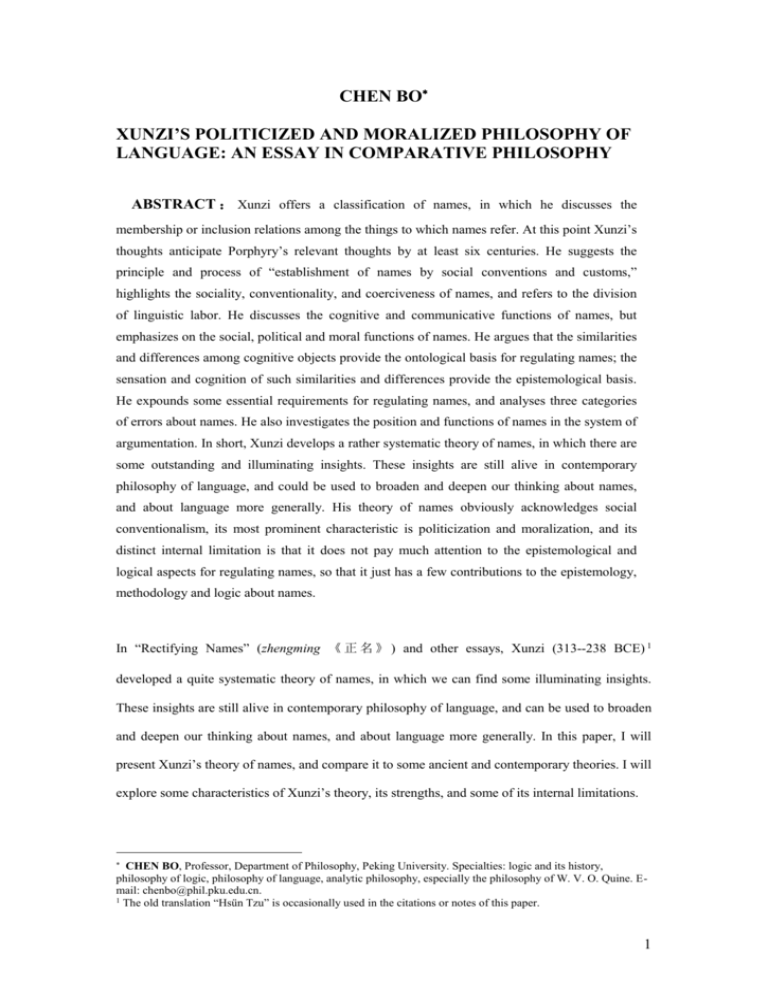

Xunzi`s Philosophy of Language

advertisement