Applying Six Traits to Scientific Writing

advertisement

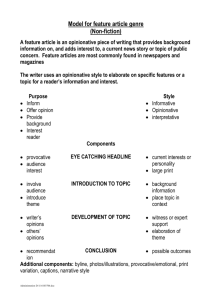

Best Practices Applying Six Traits to Scientific Writing Ideas: A clear point, message, theme or story line, backed by important, carefully chosen details and supportive information. Ideas are the heart of the message. They reflect the purpose, the theme, the primary content, the main point, or the main story line of the piece. When ideas are strong, the writing is rich with detail, original and thoughtful, highly focused and clear, and substantive. In other words, it says something; it doesn’t just meander or list ideas randomly. It doesn’t bore the reader with trivia, repetition, or unnecessary information. Organization: How a piece of writing is structured and ordered. Organization is the internal structure of the piece. Think of it as being like an animal’s skeleton, or the framework of a building under construction. Organization holds the whole thing together. You have to ask yourself: Where do I begin? What comes next? After that? Which things go together? Which can be left out? How do I tie up the loose ends? Teachers’ Resource Manual: Spring 2001 Chugach School District Applying Six Traits to Scientific Writing Scientific Writing Ideas: The ideas convey an explanation of results collected during an investigation. The ideas are clear and accurate. Details support the ideas which are being conveyed. They are descriptive but concise. Scientists note all details. Any information collected during an investigation might be important in the final analysis. Scientific Writing Organization: Scientific writing often follows a specific pattern. The basic format is: title, purpose, procedure, data, results and conclusion. The purpose tells the reader why the investigation was done and what hypothesis was being tested. The procedure gives a detailed description of the protocol followed. It should be detailed enough that someone else could repeat the work based on the description alone. The data is the raw information collected during the investigation. The results summarizes the data and includes graphs, table and analysis. The conclusion wraps the report up and explains what the data means and what was learned from the investigation. IV-13 Best Practices Voice: The fingerprints of the writer on the page - the writer’s own special, personal style coming through in the words, combined with concern for the informational needs and interests of the audience. Writing that’s alive with voice is engaging, hard to put down; voiceless writing is a chore to read. Voice is the personal imprint of the writer on the page, and so is different with each writer. Voice also differs somewhat with purpose and audience. A writer may use one voice in a note to a friend, another in a story to be read aloud to 60 listeners, and another still in a business letter or memo. Word Choice: Language, phrasing, and the knack for choosing the “just right” word to get the message across. Careful writers seldom settle for the first word that comes to mind. They constantly search for the “just right” word or phrase that will help the reader get the point. Mark Twain once said that the difference between the right word and the almost right word was the difference between “lightning” and “lightning bug”. Word choice is the use of rich, colorful, precise language that communicates not just in a functional way, but in a way that moves and enlightens the reader. Scientific Writing Voice: Teachers’ Resource Manual: Spring 2001 Chugach School District Applying Six Traits to Scientific Writing Technical writing often uses the third person. The voice is analytical and precise. The “mark of the writer” is not particularly important in technical writing. In fact, scientific writing is usually impersonal. Scientific Writing Word Choice: Words should be carefully selected. The writer should steer clear of anthropomorphic descriptions or cute analogies. Language in this format communicates in a functional way to enlighten the reader. “Flowery” and overly descriptive writing should be avoided. Scientific terms are used. However, terms should not be used unless clear understanding of the meaning of these terms is shown. Sentence Fluency: The rhythm and sound of the writing as it is read aloud. IV-14 Best Practices Fluent writing is graceful, varied, rhythmic - almost musical. It’s easy to read aloud. Sentences are well built. They move. They vary in structure and length. Each seems to flow right out of the one before. Strong sentence fluency is marked by logic, creative phrasing, parallel construction, alliteration, and word order that makes interpretive reading feel simple and natural. Conventions: Editorial correctness and attention to any detail a copy editor would review including: spelling, grammar and usage, capitalization, paragraph indentation, punctuation. Almost anything a copy editor would deal with comes under the heading of conventions. This includes spelling, punctuation, grammar and usage, capitalization and paragraph indentation. It does not include such things as handwriting or neatness. In a strong paper, the conventions are handled so skillfully, the reader doesn’t really need to think of them. Scientific writing should not be wordy. Sentences should be clear, concise and to the point. Descriptions should give the reader an understanding of the investigation performed. Scientific Writing Conventions: The writer should adhere to all standard writing conventions. Spelling of scientific terms is important (especially when reference materials are available.) Sources should be credited when appropriate. Scientific Sentence Fluency: Note: The descriptions for the 6 traits of writing and the scientific traits of writing were adapted from Nancy Norman material and material received at a NSTA workshop presented by Mary Margaret Welch. Teachers’ Resource Manual: Spring 2001 Chugach School District Applying Six Traits to Scientific Writing IV-15