Epistemology

advertisement

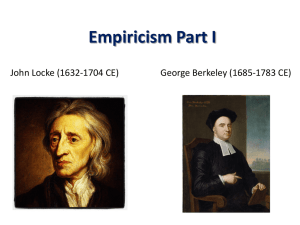

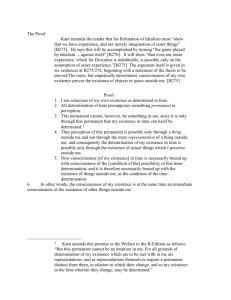

Rene Descartes and CARTESIAN EPISTEMOLOGY scepticism: Our knowledge of reality begins with doubt (in modern philosophy the famous Cartesian doubt). I must first doubt all that I can possibly doubt. I can doubt the existence of God, other selves, and the existence of the material world including my own body. Descartes goes so far as to postulate the existence of the “evil genius,” who might even be able to deceive me concerning the clear and distinct ideas I have in mathematics. subjectivism: I find that I can plausibly doubt the existence of everything except the existence of my own consciousness (the famous “Cogito ergo sum” or “I think therefore I am”). rationalism: I will accept as true only what my own reason leads me to conclude is true through my clear and distinct ideas. Even the “evil genius” is not able to deceive me concerning the existence of my own consciousness. Now because of the many imperfections I perceive within my own consciousness, I know that the idea of perfection could not possibly come from myself. Since perfection necessarily involves existence (the ontological argument), there must be a perfect Being or God. God, being perfect, could not possibly deceive me. I can now trust all of my clear and distinct ideas. dualism: Through his clear and distinct ideas, Descartes came to accept his own existence, the existence of God, of other selves, and of the world separate from my own consciousness, God’s consciousness, and the consciousness of other selves. Reality is thereby divided between consciousness (res cogitans, thinking stuff or reason) and everything else (res extensa, extended stuff or what is visible and measurable). EPISTEMOLOGY JOHN LOCKE (1632-1704) Empiricism Locke argues that the simplest way to account for all our knowledge is to assume that our mind is at first a tabula rasa or blank slate. To introduce innate ideas is superfluous and we should accept the simplest explanation (Ockham’s Razor). Since our mind is at first a blank slate, it follows that all our knowledge arises from sensation. Simple Ideas First, we apprehend through sensation simple ideas like “solidity,” “yellow,” and “motion.” Complex Ideas Second, we form complex ideas, which are (1) compounds of simple ideas (e.g., “Beauty,” “gratitude,” “a man,” “an army,” “the universe”), (2) ideas of relations (“larger than,” “ smaller than”) created by setting ideas next to each other and comparing or contrasting them, or (3) abstractions, wherein the mind separates out a feature of an idea and generalizes it (e.g., “blueness”). Primary Qualities Characteristics that necessarily inhered in material bodies, such as solidity, extension, figure, motion or rest, and number. Secondary Qualities Qualities which are nothing in the objects themselves but powers to produce various sensations in us by the primary qualities which are in the objects. Such secondary qualities are colors, sounds, tastes, odors, and tactile sensations. Degrees of Knowledge Locke distinguishes: (1) intuition, whereby the mind immediately apprehends a truth, e.g., when we know that white is not black and that three are more than two, and when I know that I myself exist; (2) demonstration, where intervening ideas are needed to perceive the agreement or disagreement of ideas, e.g., when we come to know that the three angles of a triangle are equal to two right angles and that God exists since I myself require some reality which exists in itself from eternity in order to account for my own existence ( by implication the argument agrees with the Aristotelian-Thomistic arguments to the “Uncaused Cause,” the “Unmoved Mover,” and the “Necessary Being”); (3) sensation, whereby we know the existence of things external to ourselves by their direct effect upon us through sensation (most directly I apprehend the material substance which is this desk as the necessary foundation for the primary and secondary qualities I perceive, and through reflection on the simple ideas of thinking and willing I can know the spiritual substance of the person next to me). EPISTEMOLOGY GEORGE BERKELEY (1685-1753) Empiricism Berkeley accepts Locke’s simple explanation that all our knowledge comes from sensation. However, Berkeley concludes that primary qualities are no more than interpretations of relations between secondary qualities (e.g., when I speak of “size” and “shape” by contrasting the “brown” of the “desk” against the “white” of the “wall”). There is no reason to assume the existence of any material substance. However, I do know that spiritual substance exists, since I can infer the existence of the notions of self, God, and other selves from observing the ideas which come through sensation. My own existence is immediately inferred from my ideas and sensations, upon reflection other selves are inferred, and God is inferred as the necessary First Cause, First Mover, and Being responsible for the ideas and sensations which can not possibly arise from my finite or other finite selves. It follows that God is necessary to account for all finite spiritual substances as well. For Berkeley, esse is percipi or to be is to be perceived. God explains the stability and order of all sensations and ideas, as well as the existence of other spiritual substances. EPISTEMOLOGY IMMANUEL KANT (1724-1804) Kant agrees with the empiricists that all our knowledge begins with experience. On the other hand, he agrees with the rationalists that reason supplies the form of our knowledge (the way we relate our ideas and draw our conclusions). Kant divides the mind into three faculties: intuition or perception; understanding; and reason. He then performs what he calls a transcendental analysis of each faculty: accepting as simple fact that we do intuit or perceive, understand, and reason, Kant asks “What are the transcendental conditions that make this possible?” He concludes that there are transcendental forms or categories of the mind which enable the faculties to apprehend phenomena or objects of experience. The drawback is that for Kant we can never apprehend noumenal reality or “the thing-in-itself.” Faculty of Intuition or Perception Here we arrive by transcendental deduction at the categories of space and time as the necessary a priori conditions which make our synthetic propositions concerning phenomena or objects of experience possible. Everything we experience must be experienced in space and time. Note that space and time are themselves not objects of experience. Faculty of Understanding Here we discover the synthetic a priori foundations necessary to explain the relations we perceive. These transcendental categories are unity, totality, causality, and substantiality. Like space and time, none of these are objects of experience themselves. Faculty of Reason Here our mind produces what Kant calls “pure concepts” and does not discover any a priori conditions for further synthetic propositions. In other words, the pure concepts of reason do not relate to any possible objects of experience or phenomena. The pure concepts of reason are God, soul, freedom, justice, and immortality. These become the necessary conditions for our practical reason or moral judgment. The simple fact that we do make moral judgments indicates the need for freedom, justice, and soul. Furthermore, Kant argues that morality demands as the summum bonum or highest good that our will and feelings come into perfect harmony with what morality or moral law demands. He argues that we need immortality to accomplish this and attain happiness, which requires a harmony of will and Nature, which only God can bring about. Epistemology - the branch of philosophy that studies the nature, sources, limitations and validity of knowledge. Rationalism Rationalism - the position that reason alone, without the aid of sensory information, is capable of arriving at some knowledge, at some undeniable truths. Basic knowledge = arrived at by perception. Perception is the process of seeing, hearing, smelling, touching and tasting by which we become aware of ordinary objects. Rationalists believe that we can acquire accurate knowledge about the world simply by looking into our minds. Knowledge = a priori - pertaining to knowledge that is logically prior to experience; reasoning based on such knowledge. The dilemma: How can we know anything about the world without first observing it? What about the mathematician? Many laws of nature have been established outside of sensory observation? math (analytic geometry, algebra, calculus, trigonometry) physics logic Remember: rationalists do not necessarily believe that knowledge is arrived at through reason alone. Knowledge can also be arrived at by sensory observation ie. a giraffe has spots. And then we have Descartes: René Descartes - an extreme rationalist. He believes that the mind is entirely separate from the body. This idea is known as Cartesian dualism. Descartes claims that the senses cannot be trusted. Our sense perceptions may = dreams/hallucinations. Therefore the senses distort our view of reality = unreliable knowledge source. Descartes soon came to doubt everything that he could not prove to be certain. The one certainty = that he exists. Confirmation of existence: I think therefore I am. He believes that all knowledge is acquired by the mind and not by the senses. Empiricism empiricism - the position that knowledge has its origins and derives all of its content from experience. A reaction to rationalism To empiricists, knowledge is a posteriori = pertains to knowledge stated in empirically verifiable statements; inductive reasoning. John Locke - claims the mind is a blank slate on which experience makes its mark. All knowledge has its origins in sense experience The dilemma: Can we trust our senses? Locke claims that our knowledge of things is really our knowledge of our ideas of things. Qualities of an object distinct from our perception = primary qualities primary qualities can be measured objectively. These qualities would exist whether we perceived them or not. OBJECTIVE Qualities that we discern from an object through observation = secondary qualities secondary qualities = qualities that we impose on an object: colour, smell, texture, etc. SUBJECTIVE George Berkeley - agrees with Locke re. ideas originate with sensory experience. However, Berkeley thinks that primary qualities could also be subjective. For Berkeley, only minds and ideas exist. a subjectivist - no entity can exist without a perceiver. Berkeley (interpreted to the extreme) = solipsism - an extreme form of subjective idealism, contending that only I exist and that everything else is a product of my subjective consciousness. The dilemma: Do objects cease to exist when I am not observing them? To deal with this problem, Berkeley claims that things continue to exist even when no human mind is perceiving them, because God is forever perceiving them. Therefore objects do continue to exist outside our individual perception. Berkeley sees people as a collection of ideas. The ideas = based on subjective experience. Therefore, nothing exists independently of the consciousness of the observer. Can we really know if an object exists? David Hume - pushes Locke's view to the limit. Hume = a skeptic skepticism - in epistemology, the view that varies between doubting all assumptions until proved and claiming that no knowledge is possible. For Hume - perception = senses + experience perceptions take two forms - impressions and ideas impressions - the initial experience of an object or event ideas = memory of an object or event Prior sense impressions help us make sense of our world. If there are no impressions, there are no ideas. The dilemma: What about external reality? Hume claims that external reality is an illusion because there is no way to verify its existence. With no external reality there is: no self no God Hume holds that ideas should never be trusted unless they can be corroborated with some kind of independent sense experience. Transcendental Idealism transcendental idealism - in epistemology, the view that the form of our knowledge or reality derives from reason but its content comes from our senses. Immanuel Kant - wants to deal with the skepticism of David Hume. Kant rejects the rationalist claim to a priori knowledge. Kant also rejects the empiricist claim that all knowledge comes from sense perception. Kantian epistemology: Knowledge Content - comes from sensory experience Form - comes from reason Knowledge is acquired by our innate search for causal explanations for events. Because we are constantly looking for the causes of events, our mind is an instrument that imposes structure on the world that we live in. The world around us is a world that our mind constructs - the world must conform to our minds. The dilemma: What about a mind-constructed world that do not conform to causal laws? ie. dreams. According to Kant, events must be verified by causal effects. Scientific Method Inductive Reasoning - the process of reasoning to probable explanations or judgements. Francis Bacon: investigate nature through observation and experimentation. John Stuart Mill: use methods of induction find generalizations to support observations. Features of the scientific method: 1. accumulate observations 2. infer laws / form generalizations 3. confirm findings Inductionists tend to follow the criterion of simplicity = the belief that the world follows simpler rather than complex laws. The Hypothetical Method = beyond generalizations. William Whewell claims that scientific advancements are made by creative guessing - hypothesis = in general, an assumption, statement, or theory of explanation, the truth of which is under investigation. scientific inquiry is designed to prove or verify the hypothesis. Karl Popper contends that scientific hypotheses must be capable of being falsified through empirical observation. Falsifiability - the process of repeatedly attempting to prove an hypothesis false. If the hypothesis survives - it = CORRECT. Paradigm - a scientific research tradition or scientific model. Revolution - when an old paradigm is replaced by a new paradigm. Notes on the scientific method: 1. It incorporates elements of empiricism, rationalism and transcendental idealism. 2. Relies on inductive reasoning, generalization and repeated confirmation of new observations. 3. Uses hypotheses, verified through observation, to guide research. 4. It must be falsifiable: the theory must make predictions that, if it is wrong, can be shown to be false by observation. 5. Theories must be widely accepted by the community of scientists. 6. Scientific theories must meet five criteria: accuracy consistency reliability interconnectedness inspiring