Thushari_Welikala - Higher Education Academy

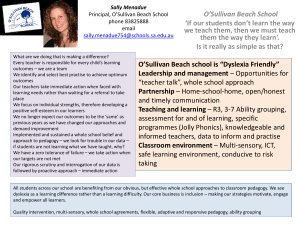

advertisement

Cultural Scripts for learning: Realizing the Pedagogy of International Higher Education in the UK Abstract The paper explores the need for rethinking the pedagogy of UK higher education within the context of internationalization. It explains that the learners coming from diverse cultures bring multiple cultural scripts in relation to learning that are shaped by different ontologies and epistemologies. A main argument is that UK higher education pedagogy does not create spaces to articulate and accommodate different ways of going about learning, thus privileging dominant narratives of learning that are appropriated within the UK academia. It suggests that the context-free nature of UK higher education pedagogy creates an illusion of diversity, constructing subtle forms of domination over different ways of viewing the world. The paper concludes that British universities need rethinking and reshaping the pedagogy to address diversity meaningfully, constructing interculturally inclusive pedagogic spaces. Introduction Internationalization of higher education is one of the key words in the current field of higher education in the UK. Remaining a main player in the international market in an increasingly unpredictable environment is given prominence by the government as well as individual higher education institutions. A market-driven system of higher education is likely not only to privilege the discourse of marketing higher education but also to occlude the discourse that is oriented around teaching and learning as well as the learners. Within this context, notions such as intercultural higher education, borderless higher 16 February 2016 education and cross border learning are in abundance in higher education discourse. Unfortunately, the connotations of such concepts in relation to higher education pedagogy are often not recognized. While using the notion of international higher education excessively, we continue to believe in assumptions and practices which do not address the complexities and the subtleties of international higher education pedagogy. Within this context, the international learners, whose experience of learning is shaped by diverse ontologies and epistemologies, find it difficult to adequately articulate their own diverse ways of knowing the world. Moreover, the learners from other cultures are not provided with sufficient understanding about the pedagogy that is appropriated in UK higher education. This situation considerably affects the way the international students go about learning in British universities. It further encourages the students from different cultures to misinterpret the pedagogy of UK universities in terms of power and politics. There have been some efforts to understand the act of learning and the problems and issues that are significant within international contexts of higher education (carrol and Ryan, 2005). The wide range of emerging literature on international higher education focuses on the different socio-cultural contexts from which the international learners come and the impact of such diversities in terms of learning in a host university in the West. The need for “supporting” the international learner who finds it difficult to meet the demands of the host learning pedagogy is one of the popular themes we find in literature on international students (Volet, 1997). The emphasis in these literatures is on the need for adjusting and assimilating the learners who come from different cultures to 16 February 2016 learn in Western universities (Ballard and Clanchy, 1984). Such literature, however, misinterpret the purpose of international higher education, thus, naively contributing to the imperialistic view of pedagogy within international contexts. There are however, some significant attempts to understand the need for the host universities to make sense of the encounter of diverse cultures within internationalized higher education, in terms of learning and teaching (Palfreyman, 2007; Mclean and Ransom, 2005). However, they do not particularly focus on the pedagogy of international higher education in terms of power and politics embedded as they have been felt by the students themselves. This paper, therefore, discusses how the UK higher education pedagogy empowers a particular way of knowing, which is appropriated within British university context, while marginalizing the alternative ways of making knowledge that are familiar to international students. This paper comes from an empirical study conducted with international students in a particular postgraduate university in the UK. It is significant to note that, even though, the opportunity sample used in this study comprised students from diverse parts of the world, the notion of culture, as it is used in this paper, does not have direct implications to geographical locations from which the learners come. Iemployed active interviewing to construct narratives with learners about their experience of learning in a British university. The interviews were conducted with the assumption that all processes of knowing are socially constituted. Hence, the context, culture as well as the relationship between the researcher and respondents during the interview conversation was supposed to shape the meanings constructed. 16 February 2016 The study revealed that there are diverse cultural scripts for learning in different cultures. The notion of cultural scripts reflects the generalized action knowledge which informs how people make sense of situations and which also guides their action in particular contexts. The stance adopted in the paper views culture as the collection of stories people tell about themselves, about living and their meanings (Bruner, 1996). Hence, learning culture consists of the stories learners told about learning. Different cultural scripts for learning emerged in terms of activities for learning: talking, writing, reading and thinking and role relations between teachers and students as well as peer relations among students for learning. These diverse cultural scripts for learning did not necessarily harmonize with the pedagogic narratives and practices, advocated by the host university in the UK. Empowering or excluding? The pedagogical thinking as well as practices within the UK, (and the other Western higher education systems), is assumed to equip the learner with the skills and opportunities to initiate his or her own learning. While certain higher education pedagogic practices in particular parts of the world are assumed to use reproductive models of pedagogy, UK higher education system seems to hold the view that their pedagogic practices provide the learners with spaces to gain agency, promote critical thinking, enabling them to face the challenges of the postmodern complexity (Dunbar, 1988). However, the experiences of some international students learning in British universities tell stories which contradict such views in relation to UK higher education. Roger, the PhD student from Ghana mentioned that: “the self-directed, liberal learning they say they have here, [in British universities] is not true. You know, when I was doing MA… there was this gentleman who continuously 16 February 2016 disturbed the lesson. He went on telling his own experience which was not important for me at all. He would never stop. And the teacher didn’t do anything to stop him. This happened every day during that lesson and for one whole year, I did not learn anything...none of us learned anything… those who can talk will always dominate the class”. Thus, there are occasions when students from other cultures find that the freedom of initiating learning can empower certain learners while others will experience the illusion of freedom. Zeema, the university teacher from Brazil in her third year of PhD described that: “When we talk they are not patient to listen to our accent. When I talk with other international students, I got to know that their voices are not heard and they are not happy and not feeling comfortable. And it is always the English talking… and also, u see, we are not for this talking, talking, taking thing all the time. What happens is that you sit and listen to their stories”. The views of students suggest that within the liberating pedagogy, there are often spaces for certain learners to achieve power over others who do not share the values, and resources appropriated within the dominant pedagogy. For instance, Zeema’s experience implies that lack of fluency in English language, as well as her different script for talking silence her within the pedagogy which is said to be promoting the participation of individual learners. 16 February 2016 The illusion of equity Western pedagogy assumes that knowledge within higher education contexts is supposed to be co-constructed through dialogue rather than transmitted from teacher to the leaner. Hence, confrontational verbal exchanges and critical questioning during group discussions are highly appreciated. However, according to Pat, the South African university teacher: “we need to tell them that we have something important to tell. The British think what can we learn from Africans? Indians? We know… we know…. You know that … boy when I was describing my experience, he said it is just simplistic. How can one’s experience be simplistic? And Thompson [the teacher] did not say anything to stop him...” The story of Pat implies the power issues intertwined within the pedagogy, which provides opportunities for some learners to dominate the context of learning. There are possibilities within the pedagogy for certain ways of knowing to be suppressed. This contributes to creating ‘better’ knowledge, rather than negotiating among diverse ways of making knowledge (Appadurai, 1996). Japanese, Chinese, Indian as well as Italian learners highlighted that it is difficult for them to participate in group discussions since they are not used to criticizing other’s view points openly. Sheng-Yu from China mentioned that: “..We are not for this arguing, questioning, and critically reviewing others’ points of view. That is our cultures. In China we have self criticism”. 16 February 2016 Akihiro from Japan holds a similar view regarding talking for learning, which affect the way they contribute to the pedagogic situations in their host university: “Here, I have to be critical of every thing. Even while talking, these English people are arguing critically. They talk as if they are writing as assignment. We never ever do that in Japan…The teachers here think we do not know anything. You talk, they think they know everything. We do not criticize others openly… We don’t like to confront others. We are not passive … But we think critically and listen critically while the lesson is going on” while describing their ways of going about talking for learning, he rejects the learner identity constructed for them as “passive learners” (Renshaw and Volet, 1995). Akihiro also highlighted that there are no spaces or opportunities for the learners with different cultural scripts for learning to negotiate with the UK higher education pedagogy. The only possibility is that the learners have to adjust to the host university pedagogy. As Koehne (2006) points out, the Western academia tries to create a desire in learners to embrace the idea that valuable knowledge and ways of making knowledge can be found in the West. However, the international students do not seem to always accept or value such discourses and they even question them or reject them. Self-initiated learning There are occasions when learners make sense of the host university pedagogy in terms of power and monopoly held by the UK universities in the act of knowledge making. 16 February 2016 ““I have been using English for years, as a person with a title in our ministry. Never felt inhibited or anything. I knew I know the language. When I was sent the paper to write a critique about ….for my qualifying essay…., send me from A to Z, they go on to say… you make sure you have quoted others and put them in the bibliography…as if I have never been to school. I felt it. Why send all these details? I know how to review an article. You know, this is how they teach us to write in their way”. Oliver, the officer from the Ministry of Education in Malawi described how the reshaping of his way of going about learning, as it is appreciated within his host university in the UK, began even before he started his course of study. The act of imposing the dominant ways of knowing on the international learner also constructs the need for ‘supporting’, providing ‘pastoral care’ (Kumar, 2003) for those who have deficiencies (Volet, 1997) in adjusting to the dominant stories of learning. However, Oliver seems to understand the power issues lying beneath such attempts and even rejects the virtual monopoly held by his host university in terms of making knowledge. Yasin from Taiwan described her experience in this manner: “Because they have written a lot, done lot of research, they have the authority ... Every thing is in their point of view… Never even say why their ways are better…. I don’t think that it is learner-centered in any way.” 16 February 2016 Towards an Intercultural Pedagogy Alternative ways of being and viewing the world will naively be marginalized or ignored within the British university context, encouraging the learners to adjust to the dominant ways of going about learning that are appreciated by the UK universities (Nines, 1999). Within this context, the opportunity of making use of the encounter of diverse ways of knowing to enrich the pedagogy of international higher education is ignored. The mere presence of international students within the university premises would not create an international or borderless teaching- learning environment. Intercultural higher education necessarily involves learners coming from diverse cultures of learning and bringing multiple narratives of learning with them. Yet, unfortunately, the epistemologies and the ontologies embedded in diverse cultural scripts learners bring in to international contexts of higher education are either considered insignificant or inadequate. The pedagogy seems to suggest that the need for change into the dominant ways of making knowledge is the focal point for successful international higher education. However, learners coming with different cultural scripts for learning do not readily embrace the host pedagogy. Instead, they question the need to follow certain dominant ways of making knowledge and their applicability in different cultures of learning. Some learners even reject the idea of totally immersing into the host way of going about knowledge: “They talk about this global higher education. But, we only learn how to learn as they do... nothing global about it...” (Stella; Bulgaria). 16 February 2016 Advocating a particular dominant way of learning has resulted in misrecognizing the meaning of international higher education; the provision of wider opportunities to experience diverse ways of making sense of the world. The main argument is that the encounter of diverse cultural scripts for learning within the contexts of international higher education should open up avenues for the academics and the learners to construct opportunities for learning between cultures. Learning between cultures Different cultural scripts for knowing, however, are not easily understood and welcomed within UK higher education context. The common interpretation of difference is that it is a deficiency on the part of the learners. The universities can promote spaces where the academics as well as the learners can articulate and accept varying ways of constructing knowledge. Such spaces will promote the view that learning is mediated by culture and that learning is more complex than an act of following a particular dominant story of making knowledge. More opportunities need to be created for the learners and teachers to story and restory their own ways of going about knowing (Welikala and Watkins, 2008). These opportunities would gradually develop intercultural fluency among learners as well as between learners and teachers. Intercultural fluency encourages dialogue and understanding between cultures and it also invites people to be reflexive of their own cultural ways of doing teaching and learning. Intercultually fluent dialogue will lead to understanding the act of learning as a complex experience which at the same time transcends and gets embedded in socio-cultural boundaries. This context would welcome 16 February 2016 different narratives of learning for constructing rich and complex spaces of intercultural learning, in which the learners and teachers learn from one another. Conclusion The paper suggests the need to recognize the significance of the diverse cultural ways of knowing the learners bring into the UK international higher education pedagogy in creating interculturally rich teaching and learning spaces. Misrecognition of different ways of learning as deficiency on the part of learners restricts the opportunities of making sense of international higher education pedagogy in the global context. It also indicates the need for using the presence of diverse cultures of learning to create an inclusive pedagogy, promoting collective empowerment (Canagarajah, 1999) among learners, who will be able to face the multiple challenges in the super complex world (Barnett, 2000). Continuation of a particular dominant pedagogic story in this fluid postmodern world will not enrich the experience of teaching and learning. Hence, the international contexts of higher education have to understand that the focus today has shifted from learning from the Western culture to learning between cultures. International higher education thus needs to construct pedagogies that negotiate new ways of relating to different cultural ways of knowing. New hybrid pedagogies will emerge within a context in which multiple narratives of learning are accommodated, appreciated and articulated, thus reshaping the UK international higher education as uniquely international. 16 February 2016 Reference Appadurai, A. (1996). Modernity at Large: Cultural Dimensions of Globalization, Minneapolis, M.N: University of Minnesota Press. Ballard, B. and Clanchy, J. (1984). Study Abroad: A Manual for Asian Students, Malaysia: Longman. Barnett, R (2000) Realizing the University in an Age of Super Complexity. Buckingham: SRHE and Open University Press. Bruner, J. (1996).The Culture of Learning, Cambridge: Harvard University Press. Carrol, J. and Ryan, J. (2005). Teaching International Students: Improving Learning for all, London: Routledge. Dunbar, R. (1988). Culture-based Learning Problems of Asian Students: some Implications for Australian Distance Educators, ASPESA papers: 10-21. Koehne, N (2006) “(Be)Coming, (Be)Longing: Ways in which International Students Talk about themselves” Discourse: Studies in the Cultural Politics of Education 27, (2) 241-257. Kumar, M. K. (2003). "Strands of Knowledge: Weaving International Student Subjectivity and Hybritiy into Undergraduate Curriculum." Melbourne Studies in Education 44(1): 63-85. Mclean, P. and Ramson, L. (2005). Building Intercultural Competencies: Implications for Academic Skills Development. Teaching International Students. J. Carrol and J. Ryan, London: Routledge. Palfreyman, D. (2007). Learning and Teaching across Cultures in Higher Education, Palgrave: Macmillan. 16 February 2016 Renshaw, P. and Volet, S. (1995). "South-East Asian Students at Australian Universities: A Reappraisal of their Tutorial Participation and Approaches to Study." Australian Educational Researcher 22(2): 85-106. Rogers, C., Ed. (1994). Freedom to Learn, Upper Saddle River, NJ: Memil. Trahar, S. (2007). Teaching and Learning: the International Higher Education Landscape. some theories and working practices., http://escalate.ac.uk/3559. 2008. Volet, S. (1997). Internationalization of Higher Education: Staff and Students' Academic and Social Adjustments. Internationalizing Malaysian Higher Education: towards Vision 2020. M. Berrell and K. Kachar, Kuala Lumpur, Malasian: YPM Publications: 31-41. Welikala,T.and Watkins,C. (2008). Improving Intercultural Experience: Responding to Cultural Scripts for Learning, London: Institute of Education Publications. 16 February 2016