Putting the Earth in the Sky - The Hebrew University of Jerusalem

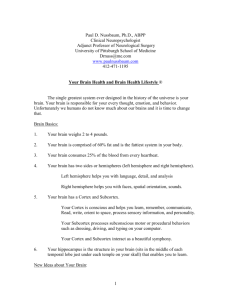

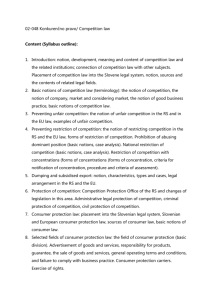

advertisement

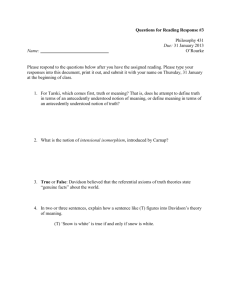

Earth in the Sky: Scientific and Personal Aspects of the Concept of Earth Yaron Schur (schurfa@netvision.net.il), Hebrew University of Jerusalem, Israel Nicos Valanides (nichri@ucy.ac.cy), University of Cyprus, Nicosia, Cyprus Abstract The way students integrate scientific and personal aspects of their conceptions of earth was investigated using 16 eighth-grade students (14 year-olds). Students related to pictures of the moon and the earth after learning a whole year about the concept of earth and were asked to draw the earth. Students’ conceptions were identified from their drawings and their own explanations. This approach differs from previous studies (Nussbaum,1971, 1985; Baxter, 1989; Vosniadou, 1994), where the interviewers identified students’ conceptions based on information given in interviews. In this study, three students put the earth on the sky, while another one claimed that she had never seen the earth. In her drawing, she expressed strong emotions in relation to science learning. Students’ drawings indicated a combination of their personal relation to the concept of earth with other learnt information. Keywords: personal relation to concepts, drawing concepts, students’ drawings, the concept of earth. Introduction Students’ conceptions of Earth received much attention in the field of science education. The emphasis was mostly on seeking similarities among children from different countries and cultures. Different researchers have also concentrated on defining the stages of development from the initial conceptions of children through to the accepted scientific concept (Nussbaum, 1971, 1985; Baxter, 1989; Vosniadou & Brewer, 1990; Vosniadou, 1994). In an article summarizing the research literature, Driver, Squires, Rushworth and Wood-Robinson (1994) concluded that the differences among researchers were only minor and proposed an integrated model describing the development of the concept of Earth among children. This approach ignored however any differences among students. Thus, we adopted a different approach of interviewing children that could lead to the identification of the influence of personal and cultural characteristics on children’s conceptions of the Earth. Though it seems that science education has dealt with all the aspects of the understanding of students of the concept of earth, we would like to show a different perspective of it. We claim that students involve their personal feelings and emotions in understanding scientific concepts. This affective side was shown in an experiment that was held with 16 students aged 14, nine out of them being from an Ethiopian origin. The students were asked to draw the earth and their places in relation to it. In several drawings of the concept of earth, one could see the anxiety with which students learn science. For many students, science learning represents a knowledge that belongs to a different culture or to different religious beliefs. This fear of science can be seen in several of the drawings of the students especially those from Ethiopian origin. The results of the experiment show a much lower profile of notions of the earth than predicted by several studies of students of the same age. What are the sources of the differences between students in relation to the concept of earth? In the theoretical 2 background, we will relate to the description of former studies to the ages of the students, their academic levels, their cultural background and the way they were taught in the classroom. In all of the above categorizations there are disagreements among different scholars. In the analysis of the drawings of students of the earth, we will relate to these topics and add the students’ personal aspects. Theoretical Background The developmental sequence of the concept of earth Nussbaum (1971, 1985) offers the first and the most detailed description in the professional literature relating to the developmental sequence of children’s concepts of the Earth. He refers to these concepts as “notions” and describes five notions progressing from the perception of the Earth as a flat surface with an absolute frame of reference for up and down, to the scientific notion of the Earth as a sphere surrounded by a huge space, with up and down defined in terms of the center of the Earth as the frame of reference. Driver, Squires, Rushworth and Wood-Robinson (1994, p. 3) relate to Nussbaum’s sequence in the introduction of their book that offers an up-to-date account of the research into children’s ideas in scientific concepts which are relevant to secondary science. They present the general scheme of the development of the notions from the more egocentric view of children to a more conceptual view. 3 Figure 1. The Nussbaum developmental sequence of the concept of Earth Notion 1 – (#1) “The Earth we live on is flat and not round like a ball....They (the children ) believe that the Earth is basically flat.” (Nussbaum, 1985). The Earth is flat and on top of it is a flat sky. Nothing exists outside the zone of Earth and sky.” Notion 2 – (#2) “Children whose ideas are classified under this notion believe that the Earth is a huge ball composed of two hemispheres... The lower part is solid and is made up basically 4 of soil and rocks. People live on the plenary part of the “lower” hemispheric surface. The “upper” hemisphere is not solid: it is made of “air” or “sky” or “air and sky””. (Nussbaum, 1985, p. 181). He adds that children claim they live inside the Earth and argue that it is impossible to live upon it. The sun, the moon, and the stars are placed inside the big hemisphere of the sky. Notion 3 –(#3) “Children who hold notion 3 have some idea of an unlimited space that surrounds the spherical solid Earth... They do not use the Earth as the frame of reference for up down directions, but they rather assume the existence of absolute, Earth independent, up - down direction in cosmic space.” (Nussbaum, 1985. p.183). Notion 4 – (#4) “Children who hold this notion demonstrate some understanding of all the elements of the Earth concept. They seem to believe that we live on a spherical planet, and they know that there is space all around the Earth. They use the Earth as the frame of reference of up-down directions - i.e. up-down directions are towards and away from the Earth. Some of them might even explain falling towards the Earth as being caused by “gravity.” However, all these “correct” predictions apply to situations of free-fall upon the Earth’s surface. They seem to relate to the Earth as a whole, and do not relate up-down directions specifically to the Earth’s center.” (Nussbaum, 1985, p. 184). The addition of N4 to the N5 notion is unique to Nussbaum. For the teacher it creates the option of accepting as satisfactory the students’ arrival at N4, which is close to the scientific concept and yet much easier to understand than N5, since it relates the “down” direction to the ground in general, rather than to the center of the huge sphere which is called Earth. Notion 5 – (#5) It is the scientific concept. “Children who held this notion demonstrated a satisfactory and stable notion of the three aspects of the Earth concept: (1) a spherical planet, (2) surrounded by space, (3) with objects falling to its center.” (Nussbaum, 1985, p. 185). Can one compare children's notions of the earth relating only to their ages and countries? The possibility of characterizing in an agreed manner the development of the concept of earth among children guided various researchers to examine whether a similar developmental trajectory could be identified among children from different cultures and countries. A similar developmental sequence was identified among children in Nepal, New Zealand, Israel, England, and the United States (Mali & Howe, 1979; Stead & Osborne, 1980; Sneider & Polus, 1983; Nussbaum, 1985), but an age difference was identified between children Nepal and children in United States and Israel. This difference indicated that the rate of development was slower for Children in Nepal (Mali & Howe, 1979). The same sequence of conceptions was identified, but when “the percentage of Nepalese 12-year-olds holding each of the five notions … is compared with the percentage of American 8-year-olds … the remarkable thing … is not that the Nepali children are slower in gaining the concept (of earth), but that the development of these ideas is similar in such widely divergent cultures” (Driver et al., 1994). Thus, children get to the same sequence of concepts in different countries, but they differ at the age in which they acquire them. On the surface, one could get the impression that researchers agree on the basic questions of a developmental sequence of the concept of earth in children’s minds. But, there exist some basic questions and topics where the researchers disagree. Nussbaum (1985) relates to a sequence of the notions of earth that students acquire at 5 various ages in Israel. An analysis of the profiles of the different age groups and a comparison with the distribution proposed by Driver et al. (1994) indicates that the Nepalese distributions of 8 and 12 year-olds of the notion of earth are similar to that of Israelis of the same ages. Nussbaum (1985) indicated that a very big difference existed between second-grade students (8 year-olds) from Israel who were taught a special program compared to those who were not. Those second graders that were instructed had a better development of the earth’s notions than those uninstructed fourth graders and were similar to instructed sixth graders (12 year-olds) that took the regular class course. Thus, eight-year-old Israelis were at the same level with twelveyear-olds Israelis. Obviously, when a comparison is made between two groups of children, one has to go into details and describe the specific nature of the population. The eight year-old Americans that were compared with the Nepali twelve- year-olds had a higher development than the specially instructed eight-year-old Israelis described in Nussbaum (1985). But, not every eight-year-old American group would get such results. The comparison in Mali and Howe (1979) relates to very specific groups of children from Nepal and America. When only one group is being interviewed, one cannot generalize the results and specify the percentage of eightyear-old Americans holding notions. A meaningful comparison of the results of different groups of children can be only justified when there is a detailed description of their characteristics. The question of the percentage of people reaching the scientific level of the concept of earth There is also no agreement among researchers about the level of scientific understanding of the concept of earth, which should be taught in science classrooms. Baxter’s (Baxter, 1989) definition of the scientific notion of earth is similar to Nussbaum’s (Nussbaum, 1985) notion #4, which relates to the understanding that gravity pulls every object towards the ground, not relating to the center of the earth. Nussbaum’s scientific notion relates to the knowledge of the fact that gravity is directed to the center of the earth. In their summary of children’s ideas of the concept of earth Driver, Squires, Rushworth and Wood-Robinson (1994) related to Baxter’s definition or Nussbaum’s notions #4 and #5 as the scientific understanding of the concept of earth. The data quote in the research by Nussbaum (1985) and Baxter (1989) reveals conflicting results regarding the percentage of adult students achieving the accepted scientific notion of the concept of Earth. Nussbaum (1985), whose research related to Israeli students, showed that 70% of eighth-grade students achieved the accepted scientific notion (notions #4 and #5). Baxter, who researched 15-16 year old students in England, claimed that only 20% of them achieved the accepted scientific notion. This disagreement is quoted in Driver, Squires, Rushworth and Wood-Robinson (1994). Adding to the confusion is Mali and Howe (1979) research that shows that 40% of the eight-year-olds American children reached scientific understanding of the concept of earth. Again one can say that one has to relate specifically to the characteristics of each group of children, and there is no general agreement on the percentage of students who reach scientific level at any age. Does the academic level affect the notions of the earth held by children? 6 The question is further interwined with the fact that the group of children who were interviewed in Israel came from a school with high level of achievements in Jerusalem. In Nussbaum’s graph one can see that 70% of the eight-graders got to the scientific understanding of the concept of earth (notions 4 and 5), with 50% reaching notion 5. In another school for low functioning students in Jerusalem, the distribution of the concepts of earth of 15-year-olds was much lower than that of Nussbaum’s 14years-old with only 11.1% reaching the scientific notions. (Schur, 1999; Schur, Skuy, Zietsman, & Fridjhon. 2001). Students from the same town in similar ages had very different distributions of the concept of earth. This shows that the notion of earth is dependent on the academic level of students. The same phenomenon is expected to be also in other countries. There are Nepali, American or Israeli children who learnt about the concept either at home or at school, and others who have not. There are many ways with which different students learn about the earth. Some ways of teaching could change students’ concepts and make them closer to the scientific understanding, and some can confuse students and make their understandings of the concept of earth worse than at the beginning of the year. Is there any evidence in the literature of cultural or personal influences on the notions of children of the earth? Diakidou (1997) found that there is a cultural influence on the breakdown of the concept of Earth among children of Native American origin who live on a reservation in the United States. Although a general trend of development similar to that found elsewhere was reported, a high percentage of these children described people as living on a flat surface within a spherical ball also containing the other cosmic objects. This description is consonant with notion #2 on Nussbaum’s developmental sequence (Nussbaum, 1971, 1985). The unique aspect of this research is that the percentage of children perceiving the Earth in this manner was higher than usual; the researcher attributed this to their culture. Different goals of teaching the concept of earth Scientific literature makes little mention of forms of educational intervention intended to lead to conceptual change in children’s notions of the concept of Earth. The only report quoted in Driver et al. (1994) relates to the intervention of SharoniDagan (1979), which took place in Israel among a population of second graders (8– year- olds) using an individual teaching method. When Nussbaum (1985) designed with Sharoni-Dagan (1979) an intervention to teach the concept of earth, its aim was to get the students to the scientific understanding of the earth according to his definition. In six sessions of 20 minutes each, there were changes in the children's notions. "While 12% of the pupils held ideas N4 and N5 (Nussbaum's notions 4 and 5) before instruction, 42% held them afterwards" (Driver, Squires, Rushworth, & Wood-Robinson,1994). A similar result, an improvement from 12.5% to 43.7%, was achieved in a classroom intervention of low functioning 15 year-olds students, Schur, Skuy, Zietsman, & Fridjhon (2001). Vosniadou (1994) states a different goal for teaching: “By the end of the elementary school years, most students seem to have constructed the concept of a spherical earth, as an astronomical object, suspended in the sky and surrounded by space and solar objects.” Vosniadou does not relate in this description to the affect of gravity on the concept of earth, which is much harder to teach than the other ingredients of the concept of earth. 7 In conclusion, the literature shows there are differences among children in their ideas of the concept of earth. The various researchers showed the similarities between different cultures in the developmental sequence of the concept of earth. However, an analysis of the same studies indicates some personal differences among children due to differences in culture and in the academic level. Some students learnt about the earth in the classroom and others did not. The differences between the students affect the way they conceive the earth. The Experiment Methodology Sixteen fourteen-year-old students were interviewed after studying for a whole year about the earth where the teacher was using a globe as an important model. Students were then interviewed using two pictures, namely, one of Aldrin standing on the moon and the other of the Earth seen from the moon. The students were asked to draw the earth, the moon and the sun, and to specifically relate to the place where they stood. The interviews were somehow different from those conducted by Nussbaum (Nussbaum, 1971; Sharoni-Dagan, 1979), where the interviewer was expected to relate to the scientific information that was included in the children’s answers and then determine which notion of earth the child held. In the present study, students were asked to draw the earth as an integral part of the interview, and several interviews were conducted with every student, while a mediated session was also conducted to examine whether a child’s conception of the earth was stable or it could be changed. All the students came from the same school. They were mainly of low academic achievement. Nine out of 16 interviewees were from Ethiopian origin. It was thus possible to examine whether there were any cultural influences affecting their conceptions of the Earth. All interviews were conducted by the first author and another specially trained researcher, Orly Cohen. The interviews guided the students to get out of the exact topics that were learnt in the classroom about the earth. Each student was asked to draw several drawings of the earth after observing each of the pictures. The interview was semi-structured and the interviewer could ask for clarifications or explanations depending on students’ answers. Results From the drawings of the students one could very clearly see their notions of the earth, which were compatible to the Nussbaum sequence. The following table shows the notions of the students in terms of the Nussbaum sequence: Table 1 Students' Notions of the Earth Based on Nussbaum's Test Notions of the Earth 1 2 3 4 5 Number of Students 6 9 1 0 0 Percentage 37.5% 56.25% 6.25% 8 None of the students held the scientific notion of the concept of earth. Only one of them held notion #3. Most of the students held notions #1 and #2. This result was surprising when one takes into consideration the students’ ages and the fact they have learnt about the earth for a whole year. One can see that school learning had little affect upon the students' notions of the earth. Table 2 Students' Notions of the Earth and Their Cultural Origin Notions of the Earth 1 2 3 Ethiopian Origin Number of students Percentage 4 44.4% 5 55.6% Other Origin Number of students Percentage 2 28.6% 4 57.1% 1 14.3% One can see that there was not a big difference between students from different cultural backgrounds. The schooling process and the academic level of the students seem to be more influential on the notions of the students of the concept of earth than their cultural background. Putting the earth in the sky Three out of 16 students drew the Earth in the sky. Nussbaum (1985) and Vosniadou (1994) relate to the fact that some children see the earth in the sky. Nussbaum (1985) categorized it as a part of notion #1. One of the drawings is shown herewith: 9 Figure 2. Drawing of a 14 year-old student from Ethiopian origin. One can see that the Earth is drawn in the sky. Some of the learnt information about the earth is connected to it. The student drew herself standing on the ground that is not a part of the earth. She drew herself without arms and detached from the ground. One can see that the student drew in the earth some scientific information she had learnt during the year in the classroom. She put the scientific information in the sky. It was not a part of the ground where she stood, but was attached to the sky. She stated, she had never seen the earth before. One can also notice that the student drew herself in a position that is not connected to the ground. One can interpret it as an expression of being insecure. Looking at the picture one can easily see that the student's notion of the earth is no. 1. She sees an endless ground below and an endless sky above. Such an analysis was done with each of the drawings of the 16 students. Parts of the interview with her is brought herewith. This part relates to the picture of Aldrin standing on the moon: "Student: Do people live on Earth? No. Question: Do you learn about countries where people don’t live? Student: They live differently. They have to wear special clothes because it’s cold, it’s always dark there, they never see daylight. Question: Do they sometimes come to visit us, or aren’t there any contacts with them? Student: Maybe they come, but I’ve never seen them. Question: Has anyone ever seen the Earth? Student: Maybe once they used to see it. Question: Can we see it now? Student: No, we can’t. But some people can go up and see it. Maybe the guy with those clothes went up to the Earth with the snow. Question: Where is the Earth? Above the clouds or below them? Student: Inside the clouds, because the clouds cover it." The student has learnt for a whole year about the Earth in geography lessons. However the picture of the moon gave her an unexpected perspective, and made her doubt if she has ever seen anything she learnt in the classroom. The 3 students who held notion 1 drew it in the sky, near the clouds and the moon, as is shown in Figure 2. Another one explained earth was the size of a model, the globe, one meter in diameter. There was no difference in her mind between the model and the reality. A mediation process The student described above (Figure 2) did not connect the Earth learnt in geography lessons with the environment where she lived. Her town, Rehovot, was not considered part of the Earth. It took some time for the interviewers to focus the mediation on the connections between the environment of the student and her understanding of the concept of the Earth. Once this connection was made, the student drew again the Earth as can be seen in Figure 3: 10 Figure 3. Drawing of the 14 year-old student after a mediation phase One can clearly see the girl drawing herself in the same manner as in the first drawing, without arms and detached from the ground. However this time the ground is a part of a round Earth. One can also observe the sun the moon and the clouds inside the Earth, in the sky. The mediation phase enabled the student to move to notion #2 (Nussbaum, 1971, 1985). One can clearly see how similar the drawing is to notion 2 as described in figure 1. The mediation phase enabled the student to move from notion 1 to notion 2 on the Nussbaum sequence. However, one can also see the personal aspects of the drawing. The way the student drew herself, with her anxiety being shown from the figure without hands detached from the ground. Discussion The interviews through the use of the astronomical pictures enabled students to draw the concept of Earth. The decision on the notion of the students was reached through the analysis of their drawings. This is different from the procedure in Nussbaum’s test, where the interviewer has to deduce the notion from the different answers that he had got. Nussbaum's procedure of interviewing children and determining their notions of the concept of earth (Nussbaum, 1971) put the decision on the shoulders of the examiner. He/She would analyze the content of the interview and decide to which notion is the answers of the specific child the closest. The students were shown pictures of a man standing on the moon and of the earth seen from the moon (Schur, 1998, p. 2 & 18). As the students were not at ease with the concept of earth, they had difficulties also in understanding the pictures that were presented to them. Taking students to visit known places from new perspectives can show students' understanding of scientific concepts. It is important to see the context in which students understand various concepts. This should influence the way a curriculum to teach such concepts should be designed. 11 From the drawings of the students one could clearly see the notion of the concept of earth for each student. In most of the drawings one can clearly see the notions as were described by Nussbaum (1971, 1985) and by Vosniadou (1994). Each of the students drew several drawings of the earth that were influenced by the pictures they saw. The earth – moon context, which was wider than the context these students learnt about the earth, enabled them to construct various individual interpretations of the earth – moon system, and sometimes also to include the sun in it. Often they put the school learnt information and concepts in unexpected places. Some of them put earth in the sky, while attributing to it the properties learnt in the classroom, like longitudinal, the equator, the turning round its axis and the existence of countries on it. Overall the results of the students were low. None of them reached the scientific level of the concept of earth. One could not see any influence from the fact they learnt about the earth for a whole year. Nussbaum (1985) and Vosniadou (1994) related to the fact that children put the Earth in the sky. But they related to it as part of the children’s notion of the Earth. Vosniadou (1994) explained that this Earth helped children to explain different celestial phenomena such as eclipses. The difference between Nussbaum’s and Vosniadou’s way and ours of explaining the phenomenon of children putting the Earth in the sky is that for them it is part of the way children construct the Earth concept, and as we see it, this is a defense mechanism for the children. They try to preserve their everyday perceptions of the reality around them. Once the scientific ideas intrude, they are left out. This enables the students to get at the same time good results in the scientific test, where they give the teacher the “right” answers they learnt in the classroom and at the same time to preserve their everyday reality intact. Students’ drawings and the explanations they made in the interviews give a picture on the wealth of data that can be taken out of the personal parts of the children’s notions and can be used in order to construct classroom interactions. The mediation process of the concept of Earth to these children needs to involve sensitivity to the fact that they feel menaced by the scientific ideas. The mediated interactions should start a process of connection between the student and the scientific way of observing the environment. This dialogue should involve careful listening to the place where the student stays vis-à-vis the scientific concept. This involves understanding the student’s fear that the scientific ideas may change the way his culture or religion has directed her to observe certain phenomena.One has to establish a dialogue with the student on a wide basis, including relations to his real environment (physical and spiritual) and being sensitive to the transcending of the scientific ideas to different contexts, some of them may seem to the teacher as completely irrelevant to the scientific ideas. When such a dialogue takes place, one can expect students to make changes in their notions of scientific concepts in a relatively short time, as the menace is reduced and the factual knowledge exists. We have not yet found enough data on the Ethiopian stories or myths about the sky and the celestial objects. We have not found any evidence to show a cultural bias in the results of the students from Ethiopian origin in comparison with the other students, though their profile of notions of the earth is somehow lower than the other students. Conclusions 12 One could see that in the drawings of the subjects of the experiment one could identify Nussbaum’s sequence of the concept of earth. In the way the interviews were conducted, one could see the personal aspects of the students that were integrated to their drawings that contained also scientific data. Students may put scientific concepts, such as the concept of earth, “in the sky”, with no relevance to their life outside the classroom. They come to the science class with everything that is part of them including their emotions and anxieties. There is a risk that students will relate to the science class as completely detached from their everyday reality. Putting the earth in the sky and detaching oneself from the ground can be expressions of insecurity or maybe even anxiety. When students learn science they put themselves into the learning. It usually involves also their feelings and anxieties. If the learnt subject is not connected to the everyday world of the students, there is always a possibility that students will put the learnt concepts “in the sky”, meaning that they will not take them into their everyday life. References Baxter, J.(1989). Children’s understanding of familiar astronomical events. International Journal of Science Education, 11, 502-513. Diakidoy, (1997), Oral presentation in the EARLI conference in Athens. (incorrect reference) Driver, R., Squires, A., Rushworth, P., & Wood-Robinson, V. (1994). Making Sense of Secondary Science: Research into Children’s Ideas. New York: Routledge. Howe, A. C. (1996). Development of science concepts within a Vygotskian Framework. Science Education 80(1): 35-51. Mali, G.B. and Howe, A. (1979). Development of Earth and gravity concepts among Nepali children. Science Education 63(5): 685-691. Nussbaum, J. (1971). An Approach to Teaching and Assessment: The Earth Concept at the Second Grade Level. A Ph.D. Thesis. Cornell University. Nussbaum, J. (1985). The Earth as a cosmic body. In R. Driver, E. Guesne and A. Tiberghien (Eds.), (Chapter 9) Children’s Ideas in Science, Open University Press, Milton Keynes. Schur, Y. (1998). A Thinking Journey to the Moon, (Hebrew). Tel-Aviv: Ma’alot. Schur, Y., Skuy, M., Zietsman, A. and Fridjhon, P. (2002). A Thinking Journey Based on Constructivism and Mediated Learning Experience as a Vehicle for Teaching Science to Low Functioning Students and Enhancing their Cognitive Skills. In School Psychology International, Vol. 23 (1): 36 - 67. Sharoni-Dagan, N. (1979). The influence of Instruction on the Concept of Earth of Second Grade Children, (Hebrew). Israel Science Teaching Center, The Hebrew University of Jerusalem. Sneider, C. and Pulos, S. (1983). Children’s cosmographics: understanding the Earth’s shape and gravity. Science Education 67(2): 205-222. Vosniadou, S. and Brewer, W.F. (1990). A cross cultural investigation of children’s conceptions about the Earth, the Sun and the Moon: Greek and American data. In H. Mandl, E. De Corte, N. Bennett and H.F. Friedrid (Eds.), Learning and Instruction. European Research in an International Context, Volume 2.2. Papers of the second conference of the European Association for Research on Learning and Instruction held at the University of Tubingen, 1987. Oxford: Pergamon Press. Vosniadou, S. (1994). Capturing and modeling the process of conceptual change. Learning and Instruction, 4, 45 - 69.