Richard Cory: Point of View Analysis | Essay

advertisement

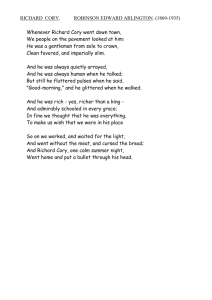

Cannon 1 George Cannon Professor Landsdown English 1101-14 21 August 2007 Point of View in Edwin Arlington Robinson’s “Richard Cory” Yvor Winters, an American critic, condemns Edwin Arlington Robinson’s poem “Richard Cory” for containing “a superficially neat portrait of the elegant man of mystery” and for having a “very cheap surprise ending” (52). It is true that because Richard Cory fits the stereotype of the man who has everything, his suicide at the end is surprising, even shocking. But the poet’s handling of point of view makes the portrait of Richard Cory only apparently superficial and the ending only apparently “cheap.” In the second line of the poem, we learn that the speaker is not an omniscient narrator, but someone with a limited view of things. He is one of the “people” of the town (38). It is as if he has cornered a visitor on a sidewalk somewhere and is telling him about a fellow townsman whose suicide has puzzled and troubled him. He cannot understand it, so he talks about it. Throughout this speaker’s narration, we learn a lot about him and his peers and how they regarded Richard Cory. Clearly they saw him as something special. The imagery of kings and nobility (“crown,” “imperially slim” and “richer than a king”) permeates their conception of Richard Cory. To them he had the bearing and trappings of royalty. He was a “gentleman,” a word that suggests courtliness as well as nobility. He had good taste (“he was always quietly arrayed”). He was wealthy. He had good breeding (he was Cannon 2 “admirably schooled in every grace”). He “glittered when he walked,” suggesting, perhaps, that he wore jewelry and walked with confidence. Because of this attitude, the speaker and his peers placed themselves in an almost feudal relationship to Cory. They saw themselves as “people on the pavement,” as if they walked on the ground and Richard Cory somehow walked above them. Even if he did not literally walk above them, they saw him as “above” them socially. They seemed to think it unusual that he was “human when he talked.” The word human suggests several things. One is that the people saw Cory as somehow exempt from the problems and restrictions of being a human being (thus “human”) but that when he talked, he stepped out of character. Another is that he, who was so much above them, could be kind, warm, and thoughtful (another meaning of “human”). They were so astonished by this latter quality that when he did such a simple and obvious thing as say “Good-morning,” he “fluttered pulses.” In the final stanza, the speaker brings out the most important differences between the people and Richard Cory. Most obvious is that he was rich and they were poor; they “went without the meat, and cursed the bread.” But another difference is suggested by the word light: “So on we worked and waited for the light.” Light in this context most apparently means a time when things will be better as in the expression “the light at the end of the tunnel.” But another meaning of “light” is revelation. Light has traditionally symbolized knowledge and truth, and it may be that this is the meaning the speaker—or at least Robinson—has in mind. If so, another difference that the people saw between Richard Cory and themselves was that Cory had knowledge and understanding and they did not. After all, they had no time to pursue knowledge; they needed all their time just Cannon 3 to survive. But Richard Cory did have the time. He was a man of leisure who had been “schooled.” If anyone would have had the “light”—a right understanding of things— then Richard Cory would have been that person. Although Robinson does not tell us why Richard Cory killed himself, he leaves several hints. One of these is the assumptions about Richard Cory held by the narrator and the “people.” Cory may have been a victim of their attitude. The poem gives no evidence that he sought to be treated like a king or that he had pretensions to nobility. He seems, in fact, to have been democratic enough. Although rich, well-mannered, and tastefully dressed, he nonetheless came to town, spoke with kindness to the people, and greeted them as if they deserved his respect. Could he have wanted their friendship? But the people’s attitude may have isolated Richard Cory. Every time he came to town, they stared at him as if he were a freak in a sideshow (lines 1-2). In their imagination, furthermore, they created an ideal of him that was probably false and, if taken seriously by Richard Cory would have been very difficult to live up to. Cory did not, at least, have the “light” that the people thought he had. His suicide attests to that. He was, in short, as “human” as they; but, unlike them, he lacked the consolation of fellowship. Ironically, then, the people’s very admiration of Richard Cory, which set him apart as more than human and isolated him from human companionship, may have been the cause of his death. Had Robinson told Cory’s story as an omniscient narrator, Winters’s complaint about the poem would be justified. The poem would seem to be an attempt to shock us with a melodramatic and too-obvious irony. But Robinson has deepened the poem’s meaning by having one of the Cory’s fellow townspeople tell his story. This presentation Cannon 4 of Cory’s character, his relationship to the townspeople, and his motives for suicide open up the poem to interpretation in a way that Winters does not acknowledge or explore. Cannon 5 Work Cited Robinson, Edwin Arlington. Tilbury Town: Selected Poems of Edwin Arlington Robinson. New York: Macmillan, 1951. Winters, Yvor. Edwin Arlington Robinson. Norfolk: New Directions, 1946.