Rivanna Watershed Virtual Tour Part 1 Narration

advertisement

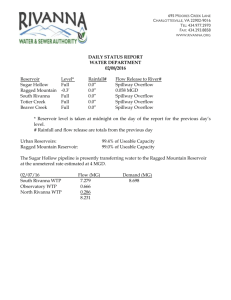

Virtual Tour of the Rivanna River Watershed 1-4 The Rivanna River begins in the Blue Ridge Mountains and flows east to become the largest tributary of the James River. The South Fork of the Rivanna River is fed by two large tributaries, the Mechums and the Moormans Rivers, in Albemarle County. The North Fork of the river has its origins in Greene County. The South Fork has been dammed to form the South Fork Reservoir to the north of Charlottesville, and is an important source of water in the urbanized part of Albemarle County. The two forks of the river join near Charlottesville, and the main stem of the river flows southeast into Fluvanna County. The Rivanna crosses Fluvanna County through Palmyra, and flows into the James river near the Town of Columbia. 5-7 A watershed is an area of land where all rainwater runoff runs downhill to the same body of water. In the example, a red line marks the highest points along the ridges around the watershed. Water flows downhill through small streams and into larger one until they all converge at one point at the bottom of the watershed (a bay or large river in this case). 8-9 The next two slides show the location of the Rivanna River Watershed in the Commonwealth of Virginia, a map of the watershed showing its location in the four counties of Greene, Albemarle, a corner of Louisa and Fluvanna. 10-12 Smaller watersheds are always part of larger watersheds. The Rivanna River flows into the James River, so the Rivanna River Watershed is part of the larger James River Watershed. The James River, in turn, flows into the Chesapeake Bay, which makes up the largest watershed on the east coast of the Untied States (occupying parts of six states, and the District of Columbia). 13-18 The land in the watershed was once totally covered in forest. When the land was settled, much of it was cleared for farming, and more recently farmland is being subdivided for residential development. The last slide in this series shows a residential subdivision being built next to Lickinghole Creek near Crozet in Albemarle County. Lickinghole Creek is a tributary of the Mechums River. 19-24 With development comes the potential for pollution of the waters of the Rivanna River and its tributaries. Three of the most common types of water pollution in the watershed (and the Chesapeake Bay Watershed in general) are sediment, nutrients and bacteria. Sediment: soil washed into streams through erosion Nutrients: principally nitrogen and phosphorous, found in fertilizers as well as human and animal waste Bacteria: usually contributed by human and animal waste Examples of erosion and a source of animal waste follow. 25-27 A list of sources of nutrients in water resource. Livestock Over-fertilized cropland Over-fertilized suburban lawns Pet waste Failing septic systems Wastewater treatment plant outflows Followed by a photograph of algae growth caused by an abundance of nutrients in the water, and another of the dangers of allowing access to streams by livestock. 28-32 A map showing stream segments that have been listed as impaired by high levels of E. coli bacteria. The following slides show creatures that use the water and some of the ways that people use the water in the watershed. This is an opportunity to have students think of other ways we use water: watering lawns and gardens, washing cars, putting out fires, cooking, manufacturing, etc. 33-34 The next section discusses how development increases the flow of runoff into streams and rivers. Impervious cover, such as parking lots, roads and sidewalks, does not allow rainwater to seep into the earth. Runoff from these surfaces washes many types of pollution into streams. 35. The increased amount of runoff that results from development also harms streams and rivers, eroding stream banks and scouring river bottoms. The 3rd photo on the slide shows a pipe that carries stormwater from a parking lot or road into a stream. When the pipe was installed, it rested on the bottom of the stream. As a result of erosion caused by an increase in flows during rainstorms, the stream bottom and banks have eroded away and the pipe has been left hanging in the air. 36 An increase in impervious cover also results in flooding when there is no place for the increase in runoff to go. 37-40 To prevent flooding, stormdrains are built to carry runoff directly into a stream or river. The 2nd slide shows 2 pipes and a flume carrying stormwater runoff into streams and rivers. The 3rd slide shows a stormwater pond for a residential subdivision. Stormwater ponds hold runoff and let it out into a stream or river more slowly through a pipe. The total quantity of the outflow remains the same, but the amount of water in peak flows is reduced, reducing the damage cause by increased runoff. The 4th slide in the series shows a cluster of five stormwater basins built to handle runoff from intensive development on Pantops, near Charlottesville. 41-43 Some solutions are suggested for preventing water pollution, as well as the flooding and stream damage caused by increased runoff resulting from development. The first is the preservation or planting of forested buffers along streams and rivers. Slide #43 shows a portion of the forested buffer around the South Fork Reservoir outside Charlottesville that was removed by a landowner interested in improving the view from his house. The buffer around the reservoir is protected by law, and the landowner was required to replant the portion of the buffer that he had removed. Forested buffers play many roles in protecting water quality. They hold soil in place, shield the ground from the impact of raindrops, allow runoff to soak into the ground and recharge the groundwater, filter out particles of sediment and other pollution, and absorb nutrients for use by trees and other plants. 44-46 A rain garden is dug into a naturally-occurring low spot in a yard. The bottom of the hole is filled with a foot of sand, 2-3 feet of soil mixed with compost fills the rest, native trees and shrubs are planted and 3-4 inches of mulch are placed on top. The rain garden: Filters out particles of pollution Takes in nutrients Bacteria and fungus in the soil breaks down many pollutants Stores excess water Allows runoff to recharge the groundwater Slide #46 shows how runoff from a driveway is filtered by grass and enters a rain garden. If the rain is heavy, the rain garden fills and the excess runoff is again filtered as it runs down a grassy swale. A second rain garden is sited to absorb and process more runoff, and any excess runs into a storm drain, reduced in quantity and improved in quality. 47 Rainwater harvesting refers to collecting and storing rainwater for later use. A 2-inch rain that that is collected from the average roof provides enough water for one person to use for a month. 48-50 There are various ways rain can be "harvested" from a rood. One rain barrel is easily filled during a short rain storm. Connecting a number of rain barrels can collect and store enough water to carry the homeowner through a dry spell. Large cisterns or water tanks can store enough water for indoor use when properly filtered and sterilized. 51 The slide of retention basins on Pantops is repeated to suggest that if every home and business in the picture had rain barrels or cisterns collecting rain water, the need for such retention basins would be reduced. 52-59 A virtual tour of the Rivanna River Watershed. Starting with the Moorman's River Watershed, which has its origins in the Blue Ridge Mountains in western Albemarle and Green Counties. A dam on the Moorman's River nestled in the mountains in Sugar Hollow forms a reservoir used by the City of Charlottesville and urban parts of Albemarle County. Slide #55 shows the Moorman's River above the reservoir. Slides #56 and #57 show the reservoir where the river enters on the right side and is released over the dam on the left. The Moorman's River wends its way through rural Albemarle County (#58) and joins the Mechum's River shortly before it flows into the South Fork of the Rivanna River (#59). 60-63 Slides of the South Fork of the Rivanna River and the South Fork Reservoir. Slide #63 shows the dam on the reservoir and the water treatment plant (on the left) that supplies most of Charlottesville's water supply. 64-67 Slides of the North Fork of the Rivanna River, which has its origins in Greene County. The northern part of this tributary flows through rural countryside. As the North Fork get closer to Charlottesville signs of development appear. Slide #67 shows a newly built house in the Advance Mills Subdivision. Along the bank of the river on the left side of the photo a strip of yellowish vegetation can be seen. This is a 200-foot riparian buffer that has been put under permanent easement to protect the river. The vegetation in this buffer will be allowed to grow naturally until it is once again forested. 68-73 The South Fork and the North Fork of the Rivanna River join northeast of the City of Charlottesville to form the Rivanna River proper. The Rivanna flows down the east side of the city and then southeast through rural Albemarle County and Fluvanna County. Slide #70 shows the Moores Creek Waste Water Treatment Plant, which empties into Moores Creek (Slide #71) just west of its confluence with the Rivanna. Slide #72 is Albemarle county and #73 is Fluvanna County. 74-75 Slides #74 and 75 show Lake Anna, formed by damming Boston Creek, a tributary of the Rivanna. Lake Anna is a very large subdivision of approximately 7,000 people. Slide #77 shows where the Rivanna River flows into the James River near the small town of Columbia.