Teacher Knowledge and Teacher Learning for

advertisement

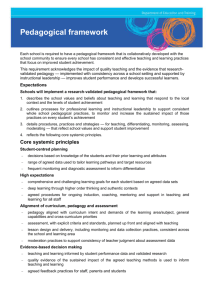

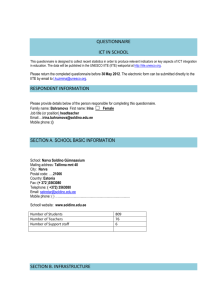

Teacher Knowledge and Teacher Learning for Pedagogical Innovation with ICT Nancy Law University of Hong Kong Email: nlaw@hku.hk Paper presented at the British Educational Research Association Annual Conference, Institute of Education, University of London, 5-8 September 2007 Abstract Teacher professional development has been identified as an important strategic component in any curriculum or pedagogical initiative as such changes call for new teacher knowledge and competence. ICT supported pedagogical innovations have attracted increasing attention from policy makers as well as practitioners in school education as well as from educational researchers. It is important to understand what challenges in knowledge (which is used in a broad sense to include skills for competent performance) teachers face in implementing and sustaining ICT supported pedagogical innovations in their own practices and what impacts different organizational and support mechanisms at the innovation level may have on teacher learning. This paper reports on an exploration of these issues using the case studies of ICT supported pedagogical innovations collected in the Second Information Technology in Education Study Module 2 (SITES M2). The analysis throws important light on understanding the interaction between pedagogical design of ICT-supported innovations, social infrastructure for change and the requisite teacher knowledge for effective implementation. Implications for policy and strategic planning of ICT integration and for the provision of professional development opportunities for teachers will be discussed. SITES M2 SITES M2 was an international comparative study of case studies of pedagogical innovations using technology involving 28 countries conducted under the auspices of the International Association for the Evaluation of Educational Achievement (Kozma, 2003). An important aspect of pedagogical innovation is the change in the roles played by the teachers and the students away from the traditional instructor-receptive learner model. (Law, 2004) analyzed the pedagogical organization and the roles played by the teachers in 130 of the case studies collected in SITES M2. It was found that these practices can be categorized into six types, scientific investigations, project work, media productions, virtual schools or online courses, task-based learning and expository teaching. Furthermore, there appears to be an interaction between the practice type and the roles played by the teachers though the relationship was not definitive. Teachers were found to be more likely to play facilitative roles in scientific investigations, projects and media productions while the teachers’ roles in task-based learning and expository teaching were essentially didactic and traditional. Roles of the teachers in virtual schools and online courses were the most highly variable, ranging from highly innovative to very traditional. In addition to examining the ways learning and teaching were organized in the SITES case studies, Law (2003) identified six dimensions (or aspects) of change of classroom practices along which cases could be compared in terms of the extent of innovativeness. These six dimensions are: intended learning objectives of the classroom practice, pedagogical role(s) of the teacher, 1 role(s) of the learner, nature and sophistication of the ICT used, connectedness of the classroom and learning outcomes exhibited by the learner. It can be seen that significant changes took place in addition to the integration of ICT into the learning process. It is argued here that these innovations can in fact be seen as disruptions where ICT played an important role. In the book The innovator's dilemma: when new technologies cause great firms to fail, Christensen (1997) introduced the concepts of sustaining and disruptive technologies. The former refers to technologies that foster improved performance of existing, established products while the latter refers to technologies that are less well developed and weaken established products in mainstream markets but have features that address specific needs in a newly emerging, fringe market. The distinction between sustaining v.s. disruptive technology lies in the market to which the technology serves. The concept of disruptive technology so defined may not immediately apply to education since we are interested in exploring the impact of ICT in publicly funded schools, and not the impact of ICT on a different “education market” such as home schooling, learning centres, etc. Instead, the relationship between technology and pedagogical practices can be conceptualized as sustaining or subversive, depending on whether the use of the technology is aimed to strengthen existing pedagogical processes to better achieve existing curriculum goals or to bring about new goals, new processes and new relationships. It is important to note here that the categorization of sustaining or subversive uses of technology does not depend on the technology alone, but also on the intended use of the technology in the specific educational context. What does it take for a teacher to be able to leverage ICT for pedagogical innovations such as the one described in the previous section? Clearly there is a lot of new knowledge involved. Mishra & Koehoer (2006) extended Shulman’s (1986) theory about teacher knowledge (which argues that a competent teacher would need to have content knowledge (CK), pedagogical knowledge (PK) and pedagogical content knowledge (PCK) for ICT-using pedagogical situations. It has been proposed that in addition to technological knowledge (TK) which is expected of the teacher when ICT is used, three further kinds of new knowledge (technological content knowledge (TCK), technological pedagogical knowledge (TPK) and technological pedagogical content knowledge (TPCK) are required in order that teachers can be capable of “understanding and negotiating the relationships between these three components of [technological, content and pedagogical] knowledge” for true technology integration (ibid, p.134). However this framework is not sufficient to encompass what it takes for a teacher to be able to make use of ICT to undertake pedagogical innovations. It is found that in many of the innovations analyzed, the teachers have to grapple with new content knowledge (CK) in order to achieve new curriculum goals. The teacher also have to master new pedagogical knowledge and skills (PK) in implementing the new pedagogical approaches that emphasize inquiry, collaboration and learning with and from peers and experts beyond the classroom walls. Furthermore, facilitating collaboration and inquiry in new content areas require new pedagogical content knowledge (PCK). In innovating, a teacher is also an agent of disruption (or innovation). To leverage ICT as a disruptive force, requires courage and motivation. Hence, a most important issue to be addressed in relation to teacher learning for pedagogical innovation is not what needs to be learnt, but why a teacher would want to learn? What motivates a teacher to put in so much cognitive, metacognitive and socio-emotional energy to make the change happen? The answer has to lie in the professional value and epistemological belief of the teacher, and these can only be cultivated . through the social, institutional and professional milieu within which the teacher lives and work. Values and beliefs cannot be learnt through instruction and changes can only take place through deeply engaging experiences over an extended period of time. Innovation is an emerging process both for the individual teacher(s) as well as the institution(s) involved. Figure 1 presents the framework for conceptualizing teacher learning for ICT-supported pedagogical innovation presented above. 2 Cognitive capacity Metaognitive capacity for inquiry and autonomous learning TK TCK Inquiry, change and improvement TPK TPCK CK PCK PK Sociometacognitive capacity for knowledge building Social and communication skills and “know-who” knowledge What needs to be learnt to innovate with ICT Students’ learning outcomes 21st Century skills The driving force for learning Educational Values Epistemological beliefs Social, institutional and professional community(ies) in which the teacher is situated. Figure 1. A Diagrammatic representation of the different capacities required for ICT-supported pedagogical innovation and contextual influences on teacher learning. 3 The above analysis and proposed framework have implications on understanding the interaction between the pedagogical design of ICT-supported innovations, social infrastructure for change and the design for teacher professional development. To be able to innovate teacher learning need to go beyond acquiring knowledge to develop meta-cognitive, social and socio-metacognitive capacities for innovation. Further, professional development must address issues of values and beliefs which provide the orientation and motivation for teacher learning. Reference: Christensen, C. M. (1997). The Innovator's Dilemma: when new technologies cause great firms to fail: Harvard Business School Press. Kozma, R. (Ed.). (2003). Technology, Innovation, and Educational Change: A Global Perspective. Eugene, OR: ISTE. Law, N., & Plomp, T. (2003). Curriculum and Staff Development for ICT in Education. In T. Plomp, R. Anderson, N. Law & A. Quale (Ed.), Cross-national Information and Communication Technology Policy and Practices in Education (pp. 15-30). Greenwich, CT: Information Age Publishing Inc. Law, N. (2004). Teachers and Teaching Innovations in a Connected World. In A. Brown & N. Davis (Eds.), Digital Technology, Communities and Education (pp. 145-163). London: Routledge Falmer. Mishra, P., & Koehler, M. (2006). Technological Pedagogical Content Knowledge: A Framework for Teacher Knowledge. The Teachers College Record, 108(6), 1017-1054. Shulman, L. (1986). Those who understand: Knowledge growth in teaching. Educational Researcher, 15 (2), 4-14. An extended version of this paper will appear in: Law, N. (2008). Teacher learning beyond knowledge for pedagogical innovations with ICT. In Voogt, J. & Knezek, G. (Eds.) International Handbook for Information Technology in Education. Springer. 4