SudanicEmpiresGroupReadings

advertisement

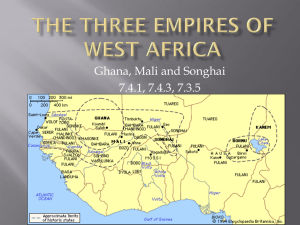

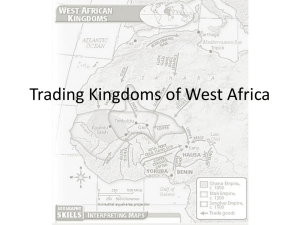

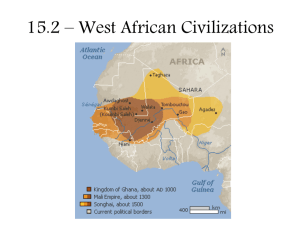

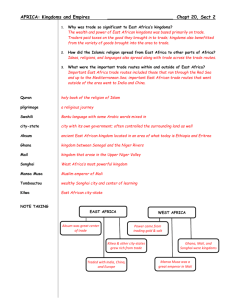

The Ghana Empire The Ghana Empire began as the camel was introduced to SubSaharan Africa and TransSaharan trade routes emerged. Ghana was the first of the three great West African trading empires, reaching its height before the introduction of Islam to Sub-Saharan Africa. During the 400sCE, it is probable that a Soninke chief succeeded in uniting the Soninke ethnic group in a small state. Historians agree that the empire’s most glorious period lasted from the 700s through the 1000s CE. Because the ruler of Ghana controlled the trade routes in the region, he was called “the master of gold” and called himself “Ghana,” which meant “warrior king.” One 9th century visitor described him as “the wealthiest of all kings on the face of the Earth.” This kingdom lasted about six centuries before being conquered by new forces from the east. The Ghana Empire survived and prospered because it was located on major trade routes. The gold and salt trade established Kumbi Saleh, Ghana’s capital, as the wealthiest city in West Africa from about 800 C.E. to 1050 C.E. Ghana was well placed to take advantage of trade. It was located midway between the desert, the main source of salt, and the goldfields of the upper Senegal River. Camel caravans crossing the Sahara brought goods such as copper and dried fruit, as well as salt that was mined in present-day northern Mali. The caravans also brought clothing and other manufactured goods, which they exchanged for kola nuts, hides, leather goods, ivory, gold, and slaves. Taxes collected on every trade item entering the kingdom were used to pay for government, a huge army which protected the kingdom's borders and trade routes, and the upkeep of the capital city and major markets. However, it was connections to the gold fields in the southwest that was essential to Ghana's political control and economic prosperity. Interestingly, Ghana never owned any goldfields of its own; the gold came from the Wangara people of the south, who needed to trade gold for salt in order to survive. Arab traders in North Africa wanted gold as much as the people of Wangara wanted salt, and both had to pass through Ghana to trade. Thus, Ghana exploited its geographic location and military power to tax individuals who traded within its borders. By the tenth century, Ghana was an immensely rich and prosperous empire, probably controlling an area the size of Texas. The ruler was acclaimed as the "richest king in the world because of his gold" by Arab traveler Ibn Haukal, who visited the region in about 950 A.D. Demand for gold increased in the ninth and tenth centuries for minting into coins by the Islamic states of North Africa. As the trans-Saharan trade in gold expanded, so did the state of Ghana. Ghana’s power came from its ability to use iron weapons to control the trading of gold and salt. Iron-tipped spearheads, lances, knives, and swords gave ancient Soninke soldiers technological superiority over their neighbors who used bone and wood. Locally obtained iron ore was also used to make tools, which made agriculture easier and more efficient, and permitted the growth of larger settled communities. The people of Ghana were thus able to capture more farming and grazing land from their weaker, less-organized neighbors and were also able to obtain horses from the Saharan nomads with whom they were in contact, which enabled them to move farther and faster. The king of Ghana maintained a strong, centralized government and absolute power. He was expected by the people to promote justice throughout the empire. Ibn Battuta, commented on the safety of Ghana, “There is complete and general safety throughout the land. The traveler here has no more reason than the man who stays at home to fear brigands, thieves, or ravishers.” The kings of Ghana and most of its inhabitants practiced traditional African religions which included avoiding disaster by pleasing the gods through prayer and ritual as well as prayer to the ancestors. They believed that one god created the world, while lesser gods ruled over daily life and nature. In order to maintain beliefs, Ghanan trading cities were divided into two sections: one for Muslim traders and one for local people. Over time, however, government officials and merchants began converting to Islam as the message of Mohammad spread over trade routes. The Ghana Empire collapsed under the onslaught of invaders from the north and west and because of economic pulls to the east and south. In the eleventh century, shortly after Ghana reached its zenith, the city of Kumbi Saleh fell to Berber invaders from the north (1076), who swept across the desert from present-day Mauritania in an effort to control the gold trade and to purify Islam, as it was practiced in Ghana. The invaders subsequently withdrew, but the kingdom of Ghana was weakened. Rebellious subkingdoms gradually made the trade routes through Ghana dangerous. As a result, the Muslim merchants moved eastward, and with the loss of trade, the kingdom of Ghana began to crumble. A terrible drought further compounded the suffering and accelerated the deterioration of the environment. By the mid-thirteenth century, the once great empire of Ghana had disintegrated, making was for the rise of the second of the great Sudanic states: Mali. The Mali Empire A European map depicting trade routes in West Africa and Mansa Musa, the ruler of Mali, holding a gold nugget. The Mali Empire began when a small kingdom within the Ghana Empire grew ever more powerful. Mali began as a small kingdom around the upper areas of the Niger River. It became an important empire after 1235 when Sundjata organized resistance against the center of the older kingdom of Ghana. After rising, Mali remained powerful for nearly two centuries. At its height, it was nearly twice the size of Ghana. Unlike the people of the older kingdom of Ghana, who had only camels, horses, and donkeys for transport, the people of Mali also used the river Niger. By river, they could transport bulk goods and larger loads much more easily than by land. Living on the fertile lands near the Niger, people suffered less from drought than those living in the drier regions further north. Food crops were grown on the level areas by the river, not only for local people but for those living in cities farther north on the Niger River and in oasis towns along the trade routes across the desert. Thus the Niger River enabled the kingdom of Mali to develop a far more stable economy than Ghana had enjoyed and contributed to the rise of the Mali Empire. Sundjata built up a vast empire that stretched eventually from the Atlantic coast south of the Senegal River to Gao on the east of the middle Niger bend. It included important gold fields and the great cities of Timbuktu, Djenne, and Gao on the Niger River and extended to the salt mines of Taghaza. Many different peoples were thus brought in to what became a federation of states, dominated by Sundjata and his people. Under Sundjata's leadership, Mali became a relatively rich farming area. The Mali Empire was based on outlying areas--even small kingdoms--pledging allegiance to Mali and giving annual tribute in the form of rice, millet, lances, and arrows. Slaves were used to clear new farmlands where beans, rice, sorghum, millet, papaya, gourds, cotton, and peanuts were planted. Cattle, sheep, goats, and poultry were bred. The Mali Empire grew and prospered by monopolizing the gold trade and developing the agricultural resources along the Niger River. Like Ghana, Mali prospered from the taxes it collected on trade in the empire. All goods passing in, out of, and through the empire were heavily taxed. All gold nuggets belonged to the king, but gold dust could be traded. Gold was even used at times as a form of currency, as also were salt and cotton cloth. Later, cowrie shells from the Indian Ocean were introduced and used widely as currency in the internal trade of the western Sudan. The Mali Empire's most famous king was Mansa Musa. Mali prospered only as long as there was strong leadership. Sundjata established himself as a great religious and secular leader, claiming the greatest and most direct link with the spirits of the land and thus the guardian of the ancestors. After Sundjata, most of the rulers of Mali were Muslim, some of whom made the hajj (pilgrimage to Mecca). The most famous haji (pilgrim to Mecca) was Mansa Musa, king of Mali and its most renowned leader. In 1324, accompanied by some 60,000 people and carrying large quantities of gold, Mansa Musa traveled along the Niger River to Timbuktu and then across the Sahara via the salt mines of Taghaza from oasis to oasis, to reach Cairo. From there he went on to Mecca and Medina. His 500 slaves, each carrying a bar of gold weighing about four pounds and 100 camels loaded with 100 pounds of gold dust each caused a sensation. In Cairo, the value of their gold dinar (coin) was depressed for a decade due to Musa’s generosity in giving away gold. Ironically, as word of Musa’s wealth spread to Europe, cartographers began to include Mali on maps of Africa, and many began to desire the wealth within that continent. Mansa Musa was an exceptionally wise and efficient ruler. He divided the empire into provinces, each with its own governor, and towns that were administered by a mochrif or mayor. A huge army kept the peace, putting down rebellions in the smaller kingdoms bordering the central part of the empire, and policing the many trade routes. Upon his return of the hajj, Musa began incorporating the achievements of Islamic civilization into Mali. Timbuktu became a center of learning, luxury, and trade, where river people met with the desert nomads, and where scholars and merchants from other parts of Africa, the Middle East, and even Europe came to its universities and bustling markets. The language of learning began to shift toward Arabic The Mali Empire collapsed when several states, including Songhai, proclaimed and defended their independence. The empire of Mali reached in zenith in the fourteenth century but its power and fame depended greatly on the personal power of the ruler. After the death of Mansa Musa, Mali lasted another 200 years, but its glory days were over. By 1500, it had been reduced to a small area and was increasingly under attack. Soon, a new center of power would arise: Songhai. The Songhai Empire The Songhai Empire began when the Songhai king took advantage of a weakened Mali Empire to extend control over ever more territory. The Songhai people had long settled along the middle region of the Niger River, using the river for transport, fishing, hunting, and agriculture. By the ninth century, this middle region of the Niger had been integrated into the state of Songhai, with its capital at Kukiya. Merchants traded with villages along the Niger and as far as the town of Gao, which had been founded by Berber merchants, attracted by the gold trade of Ghana. In 1009, the fifteenth king of Songhai converted to Islam and decided to live in Gao. Gao attracted Muslim merchants and scholars and became the most important settlement and commercial center and in due time the capital. It was in the fifteenth century, when the empire of Mali was greatly weakened, that Songhai was able to expand its territory. Sunni Ali Ber (Ali the Great) extended his rule from Gao to Timbuktu and Djenne in the mid-fifteenth century, and then conquered the whole kingdom of Mali, using a powerful army of horsemen and a fleet of war canoes. He made Songhai the largest and most powerful of all the Sudanese kingdoms. Eventually Timbuktu was restored to its former status as a great center of Islamic learning. Gao became a prosperous city of 10,000 inhabitants under Askia Mohammed Touré, a devout Muslim. After his elaborate pilgrimage to Mecca and Medina, he expanded the empire through a series of jihads (holy wars), extending his rule farther east to the Hausa states near Lake Chad and the Mossi kingdom to the south. He used Islam to reinforce his authority, to unite the far-flung empire, and to revitalize trans-Saharan trade. Although declaring Islam the state religion of Songhai, he did not force Islam on the ordinary people, most of whom retained their traditional religious beliefs. Within a few years, the Songhai Empire was considerably larger than Mali and occupied almost the entire western Sudan. The Songhai Empire survived and prospered by centralizing administrative power, revitalizing the trans-Sahara trade, and by using Islam as a unifying force. The administration of Songhai was more centralized than that of Mali. Traditional rulers were replaced by royal appointees who owed their positions directly to the king. The Songhai Empire was divided into five large provinces, each with its own governor, Islamic courts, and professional fighting force to ensure that farmers of the province paid regular tribute to the king. The main sources of government income were thus tribute from the provinces, produce from the royal farms in the Niger flood plain and the Songhai heartland, and taxes on trade. Gold, kola nuts, and slaves were traded for salt, cloth, cowries, and horses. Cloth was woven from local Sudanese cotton and in towns like Djenne, Timbuktu, and Gao, woolen cloth and linen from north Africa were unraveled and re-woven to meet local tastes. The hierarchy of the political system was reinforced by its social structure, which was similar to a caste system. At the top of the system were the descendants of the original Songhai people of Kukya. They shared political power with the king and were kept apart from the general population. They were not allowed to marry outside their own caste. Below the Kukya were the free people of the cities and towns and the members of the army. At the bottom of the social system were ward captives and slaves, who were not placed in the army but were put to work on the royal farms. Scholars traveled from all over the world to the University of Sankore in Timbuktu to study the numerous Arabic manuscripts that were housed there. The works of ancient writers like Aristotle and Plato were translated into Arabic and made available for study at Sankore. The city of Djenne was another center of learning in the Songhai realm. It also had a university with thousands of teachers who lectured and conducted research in medicine and traditional academic subjects such as theology, law, rhetoric, astronomy, history, and geography. The Songhai Empire collapsed when the Moroccans used superior weaponry to seize power and when maritime trade routes replaced trans-Sahara trade routes. The Songhai kingdom did not last long. The Islamic Empire of Morocco in North Africa seized the salt mines at Taghaza in 1585 and conquered Gao and Timbuktu, thanks to their gunfire which easily overcame the swords, spears, and arrows of the Songhai, even thought the latter had far larger numbers. Moorish soldiers occupied the Songhai cities, beginning a reign of terror that lasted well into the eighteenth century. The trade routes were no longer safe. Drought and disease also weakened the economy. In the east, the growth of Hausa states, Bornu, and the Tuareg sultanate drew trans-Saharan trade away from Songhai and the western routes. The Songhai Empire broke into several separate states. As the Moorish civilization in North Africa declined, the demand for gold and other trade goods declined and trade became less lucrative. The Sahara became more of a barrier between the Sudan and Europe. Meanwhile the Portuguese began arriving in the Gulf of Guinea in the mid-fifteenth century and began trading with coastal Africans, first in gold (thus diverting gold from the trans-Saharan trade routes) and then in slaves. Trading Empires of the South: Great Zimbabwe Great Zimbabwe was not rediscovered until 1868, and was finally excavated around the turn of the century. The temple of Great Zimbabwe and surrounding buildings, one of the greatest of preimperialist Africa, were constructed sometime after the eleventh century and abandoned after 1450. Between 500CE and 1000CE, the plateau between the Zambezi and Limpopo Rivers was settled by Bantu-speakers called the Shona. Like other Bantu migrations, the Shona were characterized by their expert iron working, which allowed them to base their economy on agriculture. Although they found little personal use for the gold which was found along their coast, they soon found that traders from the Indian Ocean Maritime system desired it and they developed a thriving trade along the coast in cities such as Sofala. They exchanged this gold for fabrics, ceramics from Asia, spices, and fruits such as bananas. They protected their mines carefully and forbade anyone from even visiting the sites were miners extracted the precious metal from heavy rocks. The rulers who controlled the gold mines and the trading routes between the coast and the mines became wealthy and powerful, creating the base for a strong political state. The state became known as Zimbabwe, and as a sign of its growing power and prestige, a capital was built, called Great Zimbabwe. In the Shona’s Bantu language, “zimba” means house and “bwe” means stone, and the central point of Great Zimbabwe was a magnificent temple built by the Shona. It was probably built for special religious and political purposes, similar to the religious structures of other societies of the time, but the exact purpose of the structure remains unknown. The Great Temple, or king’s palace, house a complex of buildings that was dominated by a granite, cone-shaped tower that rose to a height of 115 feet. Guesses about the function of this tower have ranged from a gold-filled tomb to a Muslim minaret. The palace was enclosed by a great curving wall over 820 feet long, 15 feet thick, and 30 feet high, constructed of granite stones laid in an intricate pattern. Historians believe Great Zimbabwe was abandoned sometime soon after 1450. Perhaps the pastureland around the city was overgrazed and could no longer support the population of the capital. The women, who did most of the farming, would have had to walk further and further each year to tend their crops and animals. Around this same time, areas around the Zimbabwean state declared their independence. The most successful based their power on trading gold with coastal cities, such as the great Indian Ocean port at Kilwa. The Portuguese learned of the inland empires and sent emissaries who signed a trade treaty with the most important of these. Over time, however, as the Portuguese sea, military, and economic, power grew, the Portuguese desire to extract slaves and gold from the area undermined the independence and strength of the independent trading kingdoms.