Clinical Toxicology

3.

2.

I.

Introduction to Toxicology

EV 460/660 & BI 460/660

Fall 2014

B.

A.

Clinical Toxicology

Historical Perspectives

--can be traced back to ancient times

-- Homer’s Odyssey (600 B.C.) describes Ulysses ingesting a plant to protect himself from poisoning

-- Galen (A.D. 129-200) wrote on development of a universal antidote (theriac) containing 36 ingredients to be ingested daily as a protection against poisons

-- Nicander (2nd century B.C.) described induction of emesis as a means of treating poisoning

-- use of ipecacuanha (plant root) to induce emesis was following poison ingestion was described in 1600s, today is used to make syrup of ipecac

-- use of wood charcoal as a medical treatment dates back to Greek and Roman times, used for variety of ailments including anthrax and epilepsy

-- efficacy of antidotal properties of charcoal for treatment of mercury, arsenic, and strychnine

ingestions was demonstrated by French in early 1800s

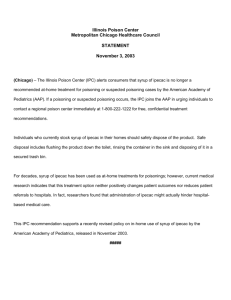

Poison Control Centers

-- first appeared in 1940s in post-war Europe, first U.S. center in Chicago in early 1950s

-- rapidly spread to number of 600 in U.S. by 1970s

-- provide valuable resources for providing information about product ingredients and recommendations for treatment of poisoning patients

-- currently less than 100 in U.S. due to regionalization, consolidation, and certification

-- American Association of Poison Control Centers – provides certification, maintains National

Poison Data System database on human poisonings http://www.aapcc.org/

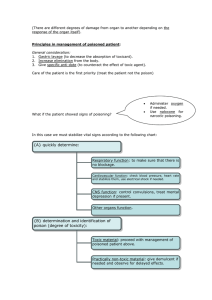

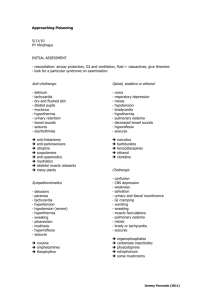

Clinical Strategy for Treatment of Poisoned Patient

-- initial phases typically take place in emergency room, but may also occur in home or workplace

-- methodical application in step-wise manner for optimal outcome of poisoning

Stabilization of the Patient

-- first priority

-- assessment of vital signs, respiratory, cardiac, and neural function

-- wide variety of signs and symptoms may be evident early in the course of toxicity

-- vary both by dose-response and by compound, for example – benzodiazepines early symptoms may be marked sedation, but comparatively mild clinical course vs. camphor results in little-to-no early signs but maybe fatal

-- some compounds induce seizures, should be controlled as part of stabilization

-- degree of stabilization varies widely from little to full ER procedures

-- once stabilized, second step can proceed

Clinical Evaluation (history, physical, and laboratory)

I. History

-- primary goal in taking history is to determine, if possible, the substance ingested or the substance to which exposed, as well as the extent and timing of exposure

-- in poisoning cases, the initial clinical history may be unreliable or unobtainable

-- in cases of intentional self-poisoning the patient may not be cooperative or may purposely give incorrect information

-- ancillary sources may be used in effort to determine substances involved, including family members, EMTs on the scene, the patient’s pharmacist or employer

-- estimates of exposure should maximize estimates of possible dose received

-- despite best efforts, exposure history may not be known and treatment proceeds as an

“unknown substance” poisoning

II. Physical Examination

-- assess physical status and mental condition, determine additional conditions such as trauma or infections

-- assessment of patient’s ability to protect his/her airway is important, gag reflex, because of possible need for “gastric decontamination”

-- if po ssible, the patient’s signs and symptoms should be classified into broad classes or toxic syndromes (toxidromes), for example, anticholinergics, narcotics, sympathomimetics, etc., this is particularly helpful if the toxic agent is unknown

III. Lab Evaluation

-- it is a misconception that definitive identification of the toxic agent can be made by initial clinical lab tests

-- unfortunately, the number of specific assays available in a clinical lab for rapid turn around time is very limited, perhaps can identify about 20 compounds on a stat basis, while the number of possible toxic agents is hundreds or thousands

D.

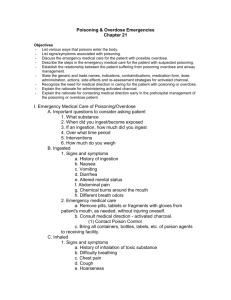

C. Prevention of Further Poison Absorption

-- for inhalation exposures – removal of person from contaminated atmosphere

-- for dermal/topical exposures – removal of contaminated clothing and washing of skin

-- for ingestion exposures-- 3 methods available, intervention ASAP after ingestion

I. Induction of Emesis by syrup of ipecac

-- most commonly used in homes at the direction of a poison control center or other medical personnel

-- contra-indicated in neonates, if ingested a caustic agent, or if CNS depression, loss of consciousness, suppression of gag reflex

II. Gastric Lavage

-- esophageal tube inserted to suck out gastric contents, followed by flush with water, then suction again, repeated cycle until only clear fluid returned on suction

-- clinical use has diminished due to questionable effectiveness, even with large bore

tube may not be able to remove all pills, capsules, etc., tube diameter is a particular problem with pediatric patients, charcoal may be as effective or more

effective than lavage

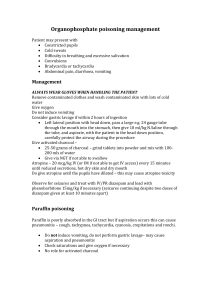

III. Charcoal

-- has been in medical use for poisoning treatment for over 150 years

-- use in treatment of oral poisoning has grown over the last few decades

-- “activated” charcoal is specifically prepared to enhance porosity and therefore surface area for absorption of chemical agents

-- charcoal is given at 1-2 g/kg of bodyweight as a liquid slurry, if the patient is unable to drink the slurry then it is administered by stomach tube

-- in general charcoal will bind well with larger organic molecules, but more poorly with low molecular weight, polar compounds

-- generally studies show that charcoal is better than syrup of ipecac

-- syrup of ipecac use has the risk of aspiration of gastric contents into lungs

-- no studies show that emesis is better than charcoal

-- charcoal is the primary method used clinically today

Enhancement of Poison Elimination

-- once the compound has been absorbed into systemic circulation, purpose is to remove the chemical from the body as quickly as possible

-- primary methods include: alkalinization of the urine, hemodialysis, hemoperfusion, hemofiltration, plasma exchange, exchange transfusion, and serial oral activated charcoal

E.

F.

Administration of Antidotes

-- there are relatively few specific antidotes available for clinical use

-- little-to-no incentive for drug companies to develop and produce, e.g., small market and the practical difficulties of performing clinical trials (required for FDA approval of new drugs)

-- mechanisms of antidotes vary, may include: physically binding with the toxic agent, enhance bodily elimination, antagonizing the toxic effects, or enhance bodily detoxification capacity for the agent

-- time course for antidote effects range from minutes following a single administration to days following multiple dosages

-- many antidotes have a low therapeutic index, e.g., a low safety margin

-- a significant part of clinical training in medical toxicology is devoted to learning the appropriate use of antidotes

Supportive Care and Follow Up

-- typically after the initial crisis, patient will be admitted to the hospital, often into ICU

-- if self-poisoning, then follow up will involve psychiatric evaluation