File

advertisement

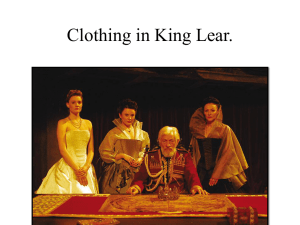

Source Citation Spotswood, Jerald W. "Maintaining hierarchy in 'The Tragedie of King Lear.'." Studies in English Literature, 1500-1900 38.2 (1998): 265+. Gale Power Search. Web. 8 Apr. 2012. In tracing the theater's role in eliciting social change in early modern England, many recent critics have focused upon King Lear as a central text, citing the breakdown of authority and service within the play as evidence of its subversive force. For John Turner, Lear portrays a world that "collapses beyond repair," and presents a prehistory in which authority and service "melt mystifyingly into one another."(1) Even Stephen Greenblatt, a forceful proponent of the subversion-containment model, concedes that Lear is Shakespeare's greatest example of the "process of containment . . . strained to the breaking point."(2) Yet models dependent upon subversion and containment often present social change as an all-or-nothing affair, occluding Shakespeare's negotiation between the forces of change and stasis.(3) Lear may have helped to bring about the "deconsecration of sovereignty";(4) it did not deconsecrate privilege, status, or hierarchy. Distinctions within the aristocracy and, more importantly, between aristocrats and commoners are enforced, both on stage and in public, through performance.(5) "[D]ifferences" in clothing, language, and manners maintain hierarchy in a "diuided . . . Kingdome" (I.iv.593, I.i.38-9).(6) Recent criticism of Lear, focusing on the crisis of authority and service in the play, has followed two distinct lines of thought. The first approach, most recently argued by Richard Strier, claims that Lear "can be seen, in part, as an extended meditation on the kinds of situation in which resistance to legally constituted authority becomes a moral necessity, and in which neutrality is not a viable possibility." According to Strier, "the quality of normative or ideal courtliness is entirely missing from the world of this play." In its absence, "touchstones of value" become "plain speech and conscientious breaches of decorum."(7) The second approach finds that Lear portrays the collapse of a feudal order founded upon the tenets of authority and service. Such readings necessarily present the sovereign as the emblem for hierarchical order. When "tragedy performs the degradation of the cultural image of the sovereign, it deprives the monarchy of its central bastion, its ultimate weapon," according to Franco Moretti. Abdication is figured as a "tyrannical act" and one which unhinges all forms of authority. The former approach presents Lear as a moral corrective of authority, while the latter finds "the principle of authority is dissolved" altogether.(8) Using Lear as a central text, both approaches assert that Renaissance drama, in subverting the relationship between authority and service, acted as a revolutionary force. In contrast to such assertions, I argue that Renaissance drama reinforces symbolic boundaries between gentlemen and commoners, even as it reveals the performative aspects of both roles. That is, though the likeness of a gentleman could be imitated on stage by a common player, the attitudes voiced and performed through this stand-in gentleman tended almost by definition to assert the privileges of the gentry. Performance subverts authority; yet it also recuperates hierarchy, reproducing systematically structured distinctions through what Paul Connerton has described as a "choreography of authority."(9) Culturally determined and symbolically bound, gentility is reproduced by individuals trained in the intricacies of elite performance. While the accumulation of wealth and property represents the means to gentility, elite performance often takes generations to perfect, for there is quite a difference between "being able to recognise a code and being able to incorporate it," as Connerton observes.(10) Though yeomen and merchants sometimes accumulated large reserves of money and land, it was often their sons or grandsons, educated at universities, who learned to perform the roles of gentlemen. The extravagant public display of behavior, gesture, and dress marks the gentle status of the elite. For elites, as Norbert Elias has observed of the French aristocracy, performance is not superfluous, but determinate of rank: In a society in which every outward manifestation of a person has special significance, expenditure on prestige and display is for the upper classes a necessity which they cannot avoid. They are an indispensable instrument in maintaining their social position, especially when . . . all members of the society are involved in a ceaseless struggle for status and prestige . . . Without confirmation of one's prestige through behavior, this prestige is nothing. The immense value attached to the demonstration of prestige and the observance of etiquette does not betray an attachment to externals, but to what was vitally important to individual identity.(11) Gentility reflects and affirms its superiority through spectacle. Performance naturalizes elevated status through a stunning display of costume and intricately performed behaviors. The lavish daily performances of gentlemen define them against the masses while subtle alterations of costume and gesture create distinctions within the elite. Although the performers themselves may change, as they invariably do over time, symbolic qualities associated with gentility remain relatively stable. Elite performance depends not upon specific actors but on fidelity to a role. Renaissance theater experimented with this performative aspect of social identity, setting itself apart from its medieval predecessor. Blurring the lines of distinction between audience and performer, the mystery plays had served a ritualistic communal function while reinforcing notions of a static and highly stratified society. Medieval drama, as Jean-Christophe Agnew notes, reflected its feudal origins, portraying social roles as divinely ordered and unalterable: "The mystery cycles had functioned, above all, as ceremonial enactments of religious and mythic charters, carefully designed to replicate governing patterns of social authority within the city and the larger society. Theirs was a relatively static tableau drama performed to propitiate a divine and unseen audience through the ritualized representation of widely held principles of ecclesiastical and social order."(12) By moving physically from the streets into the confines of the theater, Renaissance performers gained a perspective on society deniedtheir medieval counterparts. "The stage-play was now a distinct cultural form, and playing was now a distinct social calling," according to Louis Montrose.(13) Performance was no longer a ritual designed to bring absent spiritual forces to the present; rather it became the calling of professional actors who, through story and spectacle, demonstrated, among other things, the theatrical and transitory nature of the self and of society. Renaissance drama began exploring the possibility that social roles are products of performance rather than of a divine author. Sometimes assuming the part of a gentleman, sometimes taking that of a commoner, the Renaissance actor revealed, through the medium of drama, the performative nature of social roles. As Agnew notes, "the player was a little shop of characters. His extraordinary plasticity offered a living lesson in the mechanics of social mobility and assimilation."(14) However, despite the deconstructive force the Renaissance theater exerted on the perception of social roles, it did not subvert the social order. For while the medium incessantly disclosed the link between status and performance, the message of the theater, according to Robert Weimann, "was still largely dominated by traditional forms of consciousness that emphasized the very idea of hierarchy and authority as something immutably fixed to every form of social existence, from the family to the state, from apprentice to prince."(15) Whether impersonating a nobleman or a vagabond, the professional actor made alterations in dress, language, and behavior, modifying his character to conform to socially recognizable roles.(16) In The Tragedie of King Lear individual characters challenge authority; yet systems of hierarchy are reinscribed performatively, especially in the actions of disguised characters like Kent and Edgar, whose essentialized aristocratic identities are maintained in their performance of an assumed identity. Kent's foray into the lower orders, like Edgar's, demonstrates not an alliance between gentry and commoners but the social distance between them. Banished and threatened with death, each disguises himself by stripping away the outward signs of status. Defined by newly adopted roles, each hides within the social order. Borrowing "other accents" and razing his "likenesse" (I.iv.504, 507), Kent becomes Caius. "[F]ull of labours" (I.iv.510), he is no longer recognized as "this Noble Gentleman," "My Lord of Kent" (I.i.25, 27). G. K. Hunter asserts that "[i]t is the skill of the actor to remind us that the new Caius is the old Kent; but the writing seems designed to make him procure this effect by brittle virtuosity rather than 'character study'. His roles remain effectively separate from one another as he shuffles one behind the other in the manner of a card-sharper; he is not invited to draw them together as facets of a single unifying personality, but to point outwards to the different social worlds he has inhabited."(17) The play carefully keeps the laboring Caius distinct from the noble Kent. Appearing before a gentleman as Caius, Kent contrasts his outward servile appearance with his essential aristocratic worth, assuring the gentleman that he is "much more" than his "out-wall" (III.i.1517-8). Kent's transformation is so complete that the gentleman requires "confirmation" of his noble status (III.i.1517). Caius's "saucy roughnes," "plaine accent," and lowly "weedes" are not "but furnishings" (II.ii.1108, 1122, IV. vi.2498, III.i.1515); rather, in reflecting a specific social role, they determine for others "who that Fellow is" (III.i.1521). Edgar, who experiences the extremes of destitution and prosperity, demonstrates by his movement through the social order the performability of social roles; yet each role he enacts is clearly marked off from the others.(18) The differences between a Bedlam beggar, a "Pezant" (IV.v.2437), and a gentleman are defined by changes in speech, dress, and demeanor. At one point in the play Edgar comically forgets which role he is playing, confusing Gloucester by his sudden dialect shift: Glouster. Me thinkes thy voyce is alter'd, and thou speak'st In better phrase, and matter then thou did'st. Edgar. Y'are much deceiu'd: In nothing am I chang'd But in my Garments. Glouster. Me thinkes y'are better spoken. (IV.v.2214-7) The moment emphasizes the importance of performance in establishing social roles, for the blinded Gloucester is not the only character who fails to see through Edgar's disguises. As a Bedlam beggar, Edgar exists outside the social order: his lack of civility renders him invisible to those who formerly knew him. Taking the "basest, and most poorest shape / That euer penury in contempt of man, / Brought neere to beast" (II.ii.1183-5), Edgar erases all signs of his former self, griming his face with filth, blanketing only his loins, elfing his hair in knots, and enforcing charity "Sometime with Lunaticke bans, sometime with Praiers" (II.ii.1195). Edgar's nakedness is "social no less than physical," as Hunter points out.(19) Rid of all signs of status, the Bedlam beggar exists beyond the network of master and servant. Clothing himself in the "best Parrell" of Gloucester's tenant and amending his language (IV.i.2049), Edgar changes into a peasant, climbing back into the social order by visually displaying his low status. Edgar's tattered clothes and peasant dialect reintroduce him to the world of masters and servants, transforming his incomprehensible nakedness and madness into a body and mind fit for service. Ironically, both Kent and Edgar distinguish themselves through servitude. As an earl in Lear's court, Kent had challenged rules within the aristocracy governing ceremony and decorum. As Caius, Kent becomes a staunch defender of status. Vowing to teach Oswald "differences" (I.iv.593), he attempts to uphold distinctions separating gentry from commoners. Later, Kent berates Oswald for dressing out of his station, a scene made comic since it is the servant Caius and not the Earl of Kent who rebukes him.(20) In the "habit" of a peasant, Edgar serves as "guide" to his blinded father, leading him to Dover and begging in order to sustain them both (V.iii.2820, 2822). Like Ferdinand in The Tempest, both Kent and Edgar distance themselves from the play's social climbers, displaying their commitment to service and hierarchy by adopting the roles of common laborers. Duteous service earns them recognition as well as their traditional "rights, / With boote, and such addition" as their "Honours / Haue more then merited" (V.iii.29168). While Caius, the Bedlam beggar, and the peasant are all presented as products of performance, Kent and Edgar are not. As noblemen, both characters are portrayed as having an essential identity antithetical to their performative roles. Kent's essential nobility is emphasized in The Historie of King Lear, when, disguised as Caius, he is recognized as a gentleman, though not as the Earl of Kent, by another gentleman in scene 17. In The Tragedie of King Lear, Edgar subsumes Kent's role in the last two acts of the play, shifting the dramatic focus onto the trial by combat scene and Edgar's subsequent return to the aristocracy.(21) The trial by combat scene is neither "archaic" nor "semi-miraculous," as Moretti claims;(22) rather it is powerful precisely because it recalls and reflects feudal values upon which the aristocracy based their privilege. The "lore of the sword," as Craig Turner and Tony Soper assert, "was still an accepted part of the culture in late-sixteenth-century England when other medieval signs of status - certain manners of dressing and living, wearing armor, carrying a sword - had disappeared."(23) The duel remained both a symbolic testimony of an aristocrat's martial superiority and a legal right, elevating him above common legal constraints, according to V. G. Kiernan: Duelling provided a warrant of aristocratic breeding, increasingly threatened with submergence. It preserved to the entire class a military character, a certificate of legitimate descent from the nobility of the sword of feudal times, and of its title to officer the new mass armies. Duelling was in itself an assertion of superior right, a claim to immunity from the law such as a ruling class is always likely to seek in one field or another: it is for the common herd to submit to parchment trammels and shackles. For the man of noble birth it was all the more natural to put himself above the law because he, as seigneur, had been in command of justice in his own domain. On a reduced scale he was so still, in France down to 1789, in England as a JP far longer.(24) The "courtization of warriors," the internalization of violence and the centralization of force, was not a linear process, but one that moved in fits and starts, according to Elias.(25) Though the trial by combat scene may confound "us with the poverty of its reflection"(26) - and even this remains a questionable assertion since the duel continues to hold sway in innumerable Hollywood action movies - it represented, for many in Shakespeare's audience, confirmation of aristocratic status. Entering the stage nameless, the "vnknowne opposite" claims gentle status by invoking the "priuiledge" of his "Honour," "oath," and "profession" (V.iii.2784, 2760-1). His appearance, speech, and "Sword" attest to his claim (V.iii.2770), and, as Edmund testifies, reflect Edgar's nobility despite his anonymity: In wisedome I should aske thy name, But since thy out-side lookes so faire and Warlike, And that thy tongue some say of breeding breathes, What safe, and nicely I might well demand, By rule of Knight-hood, I disdaine and spurne. (V.iii.2772-6) Edmund is taken in by Edgar's performance, finding his warlike exterior and refined language sufficient evidence of his nobility. He quickly learns, however, that noble performance is ultimately tested through martial acuity. Wearing the Gloucester armor and defending the Gloucester name, Edmund appears truly noble. Yet his defeat by Edgar shows the hollowness of his claim: "Despight . . . [his] victor-Sword, and fire new Fortune" (V.iii.2763), Edmund is proven a "most Toad-spotted Traitor" (V.iii.2769). Like Oswald before him, Edmund fails with the sword, showing that he is a product of performance rather than genuinely gentle. As Jonathan Dollimore suggests, "nobility is seen to be like truth - it will out."(27) Edgar's victory, which he quickly attributes to divine intervention, naturalizes his noble status and demonstrates that his refined behaviors are not performed but a true reflection of his inner nobility, a view quickly affirmed by Albany: "Me thought thy very gate did prophesie / A Royall Noblenesse" (V.iii.2806-7). Albany's words themselves prove prophetic, for at the conclusion of the play Edgar is given sovereignty over Cornwall's former dukedom. Dismissing the centrality of the trial by combat scene, Moretti focuses instead on the last four lines of the play, which, he claims, undermine traditional categories of meaning and completely dissolve a "universal, 'higher' point of view": "The close of King Lear makes clear that no one is any longer capable of giving meaning to the tragic process; no speech is equal to it, and there precisely lies the tragedy . . . In Lear, what scant reason remains has been not only defeated, but derided and dissolved by the course of events. If at the end it is allowed the last word, this is only by virtue of that archaic, semi-miraculous duel between Gloucester's two sons; and if it returns on stage, it is only with the object of confounding us with the poverty of its reflection."(28) Edgar's final speech not only fails to recuperate his society, but, according to Moretti, the "chilling stupidity" of his words and the "drastic banalization" they impose on the play "indicates the chasm that has opened up between facts and words."Yet Edgar's inability to make sense of the tragedy befallen his kingdom is less important than the fact that he speaks the last lines of the play, and speaks them not only as a military hero but also as a ruler "in this Realme" (V.iii.2936).(29) If Edgar's "four impeccably rhymed little verses, bright with monosyllables" speak to the "nobility's inadequacy,"(30) Edgar's martial appearance and performance in the duel add weight to his words. An adept performance, as Moretti must know, can grant voice status. Dollimore recognizes the significance of the trial by combat scene, finding that it invokes "first, a concept of innate nobility in contradistinction to innate evil and, second, its corollary: a metaphysically ordained justice." Yet the unexpected deaths of Cordelia and Lear, according to Dollimore, subvert Edgar's and Albany's attempts to mark the deaths of Goneril, Regan, and Edmund as the workings of divine justice, rendering social recuperation impossible: "The timing of these two deaths must surely be seen as cruelly, precisely, subversive: instead of complying with the demands of formal closure - the convention which would confirm the attempt at recuperation - the play concludes with two events which sabotage the prospect of both closure and recuperation." Lear's death subverts dominant values as well as the social order: "the two collapse together," according to Dollimore.(31) The deaths of Cordelia and Lear, as Dollimore rightly argues, are catastrophic. Yet social recuperation is not sabotaged by their deaths; on the contrary, it is facilitated by them. In portraying Cordelia's and Lear's deaths as more consequential, as more tragic than those of any other character in the play, Shakespeare constructs a hierarchy of death. Social norms do not "collapse" as Lear does at the end of the play, for Shakespeare consistently stratifies dead bodies in the same fashion as he does live ones. As Erich Auerbach observes, Shakespeare does not "conceive of 'everyman' as tragic."(32) A dunghill and a vicious eulogy are all that memorialize the deaths of low characters like the nameless servant and Oswald. A terse eulogy given by Albany similarly marks Edmund's death: "That's but a trifle heere" (V.iii.2911). While the bodies of Goneril and Regan are accorded more dignity, being covered after death, they are also brought on stage to allow Albany to represent their deaths as the "judgement of the Heauens" (V.iii.2846). The persistence of stratification and the beginnings of social recuperation take place even before the actors have left the stage, for the "dead March" that concludes the play solemnly memorializes the status and function of the sovereign, remembering Lear as king and warrior (V.iii). The interdependent nature of court society and its dependence upon ceremony is displayed in the opening scene with the entrance of the king and his entourage. Lear leads the procession, followed on stage by the dukes of Cornwall and Albany, his three daughters, and his attendants. Lear quickly asserts his power, giving commands that are directly followed. Gloucester is dispatched to "Attend the Lords of France & Burgundy" (I.i.35), a map is ordered and quickly brought, and Lear directs his three daughters, by order of birth, to compete for his lands by announcing their love. Responding on command, Goneril and Regan publicly affirm Lear's munificence as king and father, matching his gift with absolute vows of their love. While the ceremony testifies to Lear's power, it also reflects Goneril's and Regan's high place within the social order. The privilege of attending to the king distinguishes them from others in the court. Cordelia, unlike her elder sisters, refuses to act on command, frustrating Lear's celebration of his absolute power by denying the terms of his gift. As Strier has argued, Cordelia "insists on distinguishing herself from her sisters and from the terms of the ceremony."(33) Yet in distinguishing herself, Cordelia becomes indistinguishable, for in the highly stratified society of Lear, to refuse to participate in the ceremonies of the court means "forfeiting privileges, losing power, and declining relatively to others. In short, it [means] humiliation and, to an extent, self-immolation," according to Elias.(34) Cordelia's identity, as Lear reminds her, is inextricably bound to duty and service to king and father: "Better thou / Had'st not beene borne, then not t'haue pleas'd me better" (I.i.234-5). Stripped of her dowry as well as her claim to royal lineage, Cordelia becomes "that little seeming substance . . . And nothing more" (I.i.198-200). Publicly challenging Lear's authority as father, Cordelia suffers the consequences of a spurned courtier. Having "obedience scanted" (I.i.279), she is "cast away" from court society only to be "receiu'd . . . At Fortunes almes" by the king of France (I.i.254, 278-9). The intra-elite crisis initiated in the opening scene spills over into the ranks of commoners in III.vii, as Cornwall's servant attempts to defend Gloucester, challenging Cornwall's authority. Cornwall's reaction, "My Villaine?" (III.vii.1979), as well as Regan's, "A pezant stand vp thus?" (III.vii.1981), demonstrate their indignation and surprise at having their commands questioned by a social inferior. Given the servant's social distance from Cornwall, his action is, as Strier rightly calls it, "one of the most remarkable and politically significant moments in the play." Yet it seems excessive to call this brief moment "the most radical possible sociopolitical act," or "the image of . . . peasant rebellion," as Strier does,(35) for the scene portrays not group rebellion, but individual action. Collective action gave commoners some measure of political clout, yet rioting rarely produced lasting social change. Like the grain uprisings of the late sixteenth century, most riots were conservative in nature, attempting to enforce the gentry's paternalistic role when market forces had upset the traditional relationship between elites and commoners. As Buchanan Sharp points out, "rioters had clearly defined objectives and employed only that minimum amount of force or coercion necessary to achieve those objectives."(36) When more passive means of negotiation were exhausted, the threat of collective action often proved an effective tool. As John Walter observes, "[r]iot metamorphosed fear into fact. Fact dissolved into fantasy. In confirming popular threats, riot hinted at the darker nightmare of popular rebellion." Once their grievances were redressed, the multitude typically disbanded: "Action by authority demanded inactivity by the people."(37) Yet toward "insurrection, an undeniable attempt to overturn the status quo, the Crown was quite merciless," according to Sharp.(38) Like many other playwrights and writers of the early modern period, Shakespeare frequently represents the "victory of the forces of property, order, and true religion over the many-headed monster," as Greenblatt observes.(39) In act III, scene vii of Lear, Shakespeare silences the threat of a "peasant rebellion" by reducing the multitude to a single adversary. While one servant boldly answers Gloucester's plea to "Giue me some helpe" (III.vii.1971), the other servants watch as Regan kills their fellow servant and as Cornwall finishes blinding Gloucester. Witnessing the consequences of defying authority, the servants silently follow their master's commands, thrusting Gloucester "out at gates" (III.vii.1994), and disposing of the body of their fellow servant.(40) More importantly, Shakespeare blunts the radical potential of the moment by minimizing the servant's heroic actions. Unlike Edgar's later defense of his father against Oswald, the servant is unable to defend Gloucester. In addition, the servant's battle with Cornwall, in contrast to Edgar's duel with Edmund, earns him neither honor nor status. Although Cornwall has "receiu'd a hurt" from his sword (III.vii.1996), the servant is denied the glory of his victory. Cornwall's death occurs off-stage - he does not fall at the hands of a commoner. "[S]laine" from behind by Regan, the servant falls ignobly before us on stage (III.vii.1982). Thrown "Vpon the Dunghill" (III.vii.1998), the body of the dead servant serves as a reminder to other peasants who dare to "stand vp thus" (III.vii.1981). The first servant's "rebellion" is echoed later in the play, according to Strier, when Edgar, disguised as a "most poore man, made tame to Fortunes blows" (IV.v.2427), defends Gloucester against the fortune-seeking Oswald: "They fight, and Edgar's peasant cudgel defeats Oswald's sword. This scene is clearly meant to recall the intervention of the other, actual 'bold peasant' of act 3, scene 7. The language - 'peasant . . . slave . . . dunghill' - is filled with echoes of the earlier scene. The effect is to reinforce the image of this sort of peasant rebellion as a paradigm of moral action."(41) While this scene may "recall the intervention of the other, actual 'bold peasant,'" the echoes Strier detects are not the stirrings of "rebellion." Rather, the figure of the dunghill reminds us of the futility of a "real" peasant uprising. In addition, though the language of this scene recalls the earlier one, the visual dimension is clearly different. While Oswald identifies Edgar as a commoner, calling him "bold Pezant" (IV.v.2437), the audience, who has followed Edgar's movement through the social order, is clearly meant to recognize him as a gentleman disguised. The audience knows that the "peasant cudgel [that] defeats Oswald's sword" is wielded by a gentleman, not a commoner. Instead of reinforcing the image of "peasant rebellion as a paradigm of moral action," the scene, in fact, reinscribes authority along traditional lines. Defeating Oswald with an inferior weapon, Edgar reduces the scene to comedy, making the upwardly mobile Oswald's claim to gentle status seem ridiculous while reinforcing Kent's earlier outrage that "such a slaue . . . should weare a Sword, / Who weares no honesty" (II.ii.1085-6). Further, Oswald's elevated speech is shown to be as unnatural for him as Edgar's overdone Somerset dialect: Steward. (to Edgar) Wherefore, bold Pezant, Durst thou support a publish'd Traitor? Hence, Least that th'infection of his fortune take Like hold on thee. (IV.v.2437-40) The peasant in this scene, despite Edgar's dress and speech, is Oswald. His sword, like his language, is worn merely for ornamentation. Bearing a sword yet unable to defend himself against a cudgel, Oswald is shown to lack the qualities of true gentility. In fact, Oswald's inability to use the sword effectively reveals him to be not of the blood, not gentle. Far from the "remarkable" and "significant" action of the first servant in act three, Edgar's "rebellion" is both predictable and conservative. Appropriately, Edgar reverts to a more elevated dialect when announcing his judgment over the fallen Oswald: I know thee well. A seruiceable Villaine, As duteous to the vices of thy Mistris, As badnesse would desire. (IV.v.2457-9) The effect is to naturalize the status of Edgar while marking Oswald as a social inferior whose elevated status is monstrous and more the product of a "Taylor" than of "nature" (II.ii.1066). Depicting both good and bad dukes, earls, and gentlemen, the play preserves the masterservant relationship by keeping social roles distinct. Oswald quickly makes it clear that he serves Goneril, not his "Ladies Father" (I.iv.581). Showing sympathy toward Lear, Gloucester is clearly aware that his "Master," his "worthy Arch and Patron" (II.i.941-2), is now Cornwall, not the former king. Sent to "Fetch" Cornwall and Regan and tell them that Lear "commands, tends, seruice" (II.ii.1278, 1288), Gloucester returns having "inform'd them so" (II.ii.1284). Predictably, he fears not the orders from a king "Confin'd to exhibition" (I.ii.333), but the "fiery quality of the Duke" (II.ii.1279). Although Gloucester later "incline[s] to the King" (III.iii.1637), he comes to the aid of his "old Master" (III.iii.1642), in part, because he knows a "Power [is] already footed" against Albany and Cornwall (III.iii.1637). Checking Edmund's growing power following the war, Albany, too, relies upon distinction to maintain hierarchical order: Sir, by your patience, I hold you but a subject of this Warre, Not as a Brother. (V.iii.2693-5) Albany's need to remind Edmund of his place within the social order certainly reflects a crisis of authority within the aristocracy, and it is a crisis that will continue, we can assume, until authority is again centralized under a single figure. The fact that allegiance is divided, however, does not imply that hierarchy has fallen or that authority and service are dissolved in the play. If Lear plays a role in effecting social change in early modern England, it is not the wholly subversive or revolutionary role described by recent critics. The "diuision of the Kingdome" decentralizes the realm (I.i.4), fracturing allegiance among Albany, Cornwall, and Lear; yet the social order remains intact. Authority is not destroyed but split between those with the greatest claims to land and wealth.(42) Although the play grapples with problems of succession and inheritance and tests the borders of elite society, portraying the meteoric rise of outsiders like Edmund and Oswald, it also carefully protects status distinctions. The "historical 'task'" accomplished by Lear was not the "destruction of the fundamental paradigm of the dominant culture."(43) On the contrary, The Tragedie of King Lear maintains hierarchy by validating and reproducing the "studied and elaborate hegemonic style" of the gentry.(44) NOTES 1 John Turner, "The Tragic Romances of Feudalism," in Shakespeare: The Play of History, ed. Graham Holderness, Nick Potter, and John Turner (London: Macmillan Press, 1988), pp. 83-154, 116-7. 2 Stephen Greenblatt, Shakespearean Negotiations: The Circulation of Social Energy in Renaissance England (Berkeley: Univ. of California Press, 1988), p. 65. 3 For models based on negotiation, see Theodore B. Leinwand, "Negotiation and New Historicism," PMLA 105, 3 (May 1990): 477-90; and Peter Stallybrass and Allon White, The Politics and Poetics of Transgression (Ithaca: Cornell Univ. Press, 1986). 4 Franco Moretti, Signs Taken for Wonders: Essays in the Sociology of Literary Forms, trans. Susan Fischer, David Forgacs, and David Miller (New York: Verso, 1988), p. 42. David Scott Kastan makes similar historical claims for Shakespeare's history plays. See Kastan's "Proud Majesty Made a Subject: Shakespeare and the Spectacle of Rule," SQ 37, 4 (Winter 1986): 459-75. 5 For discussion concerning the use of costuming and speech to highlight status distinctions on the Renaissance stage, see G. K. Hunter, "Flatcaps and Bluecoats," E&S, n.s. 33 (1980): 16-47; Jean MacIntyre, Costumes and Scripts in the Elizabethan Theatres (Edmonton: Univ. of Alberta Press, 1992); and Peter Stallybrass, "Worn Worlds: Clothes and Identity on the Renaissance Stage," in Subject and Object in Renaissance Culture, ed. Margreta de Grazia, Maureen Quilligan, and Peter Stallybrass (Cambridge: Cambridge Univ. Press, 1996), pp. 289-320. For discussion of behaviors and manners marking status distinctions within the elite, see Norbert Elias, The Court Society, trans. Edmund Jephcott (Oxford: Basil Blackwell, 1988); and Power and Civility: The Civilizing Process, Volume II, trans. Edmund Jephcott (New York: Pantheon Books, 1982). In addition, see Frank Whigham, Ambition and Privilege: The Social Tropes of Elizabethan Courtesy Theory (Berkeley: Univ. of California Press, 1984). 6 William Shakespeare, The Tragedie of King Lear. The Folio Text, in The Complete Works: Original-Spelling Edition, ed. Stanley Wells and Gary Taylor (Oxford: Clarendon Press, 1986). All references to Shakespeare are from this edition and will appear parenthetically in the text. My focus is specifically on The Tragedie of King Lear, the Folio text of King Lear, as opposed to the quarto text, The Historie of King Lear. For discussion of the distinct nature of the two plays and arguments against the standard editorial practice of conflating the two texts, see the collection of essays in The Division of the Kingdoms: Shakespeare's Two Versions of King Lear, ed. Gary Taylor and Michael Warren (Oxford: Clarendon Press, 1983). 7 Richard Strier, "Faithful Servants: Shakespeare's Praise of Disobedience," in The Historical Renaissance: New Essays on Tudor and Stuart Culture, ed. Heather Dubrow and Strier (Chicago: Univ. of Chicago Press, 1988), pp. 104-33, 104, 115, 114. Other critics who find the "theme of proper disobedience" central to Lear include Jonas A. Barish and Marshall Waingrow, "'Service' in King Lear," SQ9, 3 (Summer 1958): 34755; and Maynard Mack, ("King Lear" in Our Time (Berkeley: Univ. of California Press, 1972). 8 Moretti, pp. 44, 51, 56. Other critics who see Lear as a radically subversive force include Jonathan Dollimore, Radical Tragedy: Religion, Ideology and Power in the Drama of Shakespeare and His Contemporaries (Brighton, Sussex: Harvester Press, 1984); Richard Halpern, The Poetics of Primitive Accumulation: English Renaissance Culture and the Genealogy of Capital (Ithaca: Cornell Univ. Press, 1991); and Turner. Critics arguing from a Marxist perspective and claiming that Lear portrays the destruction of a feudal order and the rise of a bourgeois one include Paul Delaney, "King Lear and the Decline of Feudalism," PMLA 92, 3 (May 1977): 429-40; and Julian Markels, "King Lear, Revolution, and the New Historicism," MLS 21, 2 (Spring 1991): 11-26. 9 Paul Connerton, How Societies Remember (Cambridge: Cambridge Univ. Press, 1989), p. 74. 10 Connerton, p. 90. 11 Elias, The Court Society, pp. 63, 101. 12 Jean-Christophe Agnew, Worlds Apart: The Market and the Theater in AngloAmerican Thought, 1550-1750 (New York: Cambridge Univ. Press, 1986), p. 110. 13 Louis A. Montrose, "The Purpose of Playing: Reflections on a Shakespearean Anthropology," Helios, n.s. 7, 2 (1980): 51-74, 52. 14 Agnew, p. 122. 15 Robert Weimann, "Society and the Uses of Authority in Shakespeare," in Shakespeare, Man of the Theater: Proceedings of the Second Congress of the International Shakespeare Association, 1981, ed. Kenneth Muir, Jay L. Halio, and D.J. Palmer (Newark: Univ. of Delaware Press, 1983), pp. 182-99, 184. 16 See Hunter; and MacIntyre, especially chaps. 2 and 3. 17 Hunter, p. 37. 18 For a detailed discussion of Edgar's movement through the social order, see William C. Carroll, Fat King, Lean Beggar: Representations of Poverty in the Age of Shakespeare (Ithaca: Cornell Univ. Press, 1996). 19 Hunter, p. 33. 20 Kent's harassment of Oswald parallels Hamlet's mocking of Osric. Osric's only claim to gentility, according to Hamlet, is that he is "spacious in the possession of durt" (V.ii.3356-7), making him fit to be a "Lord of beasts" (V.ii.3355) - not a courtier. 21 For a discussion of Kent's changed role from quarto to Folio, see Michael Warren, "The Diminution of Kent," in The Division of the Kingdoms, pp. 59-73. 22 Moretti, p. 53. 23 Craig Turner and Tony Soper, Methods and Practice of Elizabethan Swordplay (Carbondale: Southern Illinois Univ. Press, 1990), p. xxii. 24 V. G. Kiernan, The Duel in European History: Honour and the Reign of Aristocracy (Oxford: Oxford Univ. Press, 1988), p. 53. For further discussion of the duel as a "corporate privilege" of the aristocracy, see M. L. Bush, The English Aristocracy: A Comparative Synthesis (Manchester: Manchester Univ. Press, 1984). 25 Elias, Power and Civility, pp. 258-91. 26 Moretti, p. 53, my emphasis. 27 Dollimore, p. 202. 28 Moretti, p. 53. 29 In the Historie of King Lear the final speech is credited to Albany, the highest ranking figure remaining in the kingdom. In The Tragedie of King Lear, Shakespeare underscores the symbolic importance of the trial by combat scene by giving Edgar the final lines of the play. 30 Moretti, pp. 55, 53, 52. 31 Dollimore, pp. 202-3. 32 Erich Auerbach, Mimesis: The Representation of Reality in Western Literature, trans. Willard R. Trask (Princeton: Princeton Univ. Press, 1953), p. 314. 33 Strier, p. 112. 34 Elias, Court Society, p. 88. 35 Strier, pp. 119, 122. 36 Buchanan Sharp, In Contempt of All Authority: Rural Artisans and Riot in the West of England, 1586-1660 (Berkeley: Univ. of California Press, 1980), p. 32. For further discussion of the "scripts" of peasant uprisings and the conservative nature of collective action, see Natalie Zemon Davis, "The Rites of Violence," in Society and Culture in Early Modern France: Eight Essays by Natalie Zemon Davis (Stanford: Stanford Univ. Press, 1975), pp. 152-87; Peter Stallybrass, "'Drunk with the Cup of Liberty': Robin Hood, the Carnivalesque, and the Rhetoric of Violence in Early Modern England," in The Violence of Representation: Literature and the History of Violence, ed. Nancy Armstrong and Leonard Tennenhouse (London: Routledge, 1989), pp. 45-76; and E. P. Thompson, "The Moral Economy of the English Crowd in the Eighteenth Century," Past and Present 50 (February 1971): 76-136. 37 John Walter, "A 'Rising of the People'?: The Oxfordshire Rising of 1596," Past and Present 107 (May 1985): 90-143, 92, 131. 38 Sharp, p. 44. For further discussion of responses by authorities to popular uprisings, see Paul Slack, Poverty and Policy in Tudor and Stuart England (New York: Longman, 1988). 39 Greenblatt, "Murdering Peasants: Status, Genre, and the Representation of Rebellion," in Representing the English Renaissance, ed. Greenblatt (Berkeley: Univ. of California Press, 1988), pp. 15-29, 15. 40 In The Historie of King Lear two additional servants are given speech, but they speak only after Cornwall and Regan have left the stage, offering aid and assistance to "the old Earle" once the Duke of Cornwall's will has been done (xiv.2024). 41 Strier, p. 122. 42 de Grazia, "The Ideology of Superfluous Things: King Lear as Period Piece," in Subject and Object, pp. 17-42. 43 Moretti, p. 42. 44 E. P. Thompson, "Patrician Society, Plebeian Culture," Journal of Social History 7, 4 (Summer 1974): 382-405, 389. For discussion of the persistence of elite authority, see Bush; and Richard Lachmann, From Manor to Market: Structural Change in England, 1536-1640 (Madison: Univ. of Wisconsin Press, 1987). I am grateful for the support provided, in part, by a Hudson Strode research scholarship from the University of Alabama. I wish to thank David Lee Miller, Sharon O'Dair, Gary Taylor, Mathew Winston, and the anonymous reader at SEL for their criticism on this paper.